Strategies for Preventing Electrode Fouling in Electrochemical Biosensors: From Materials to Clinical Applications

Electrode fouling remains a critical challenge that compromises the accuracy, reliability, and longevity of electrochemical biosensors, particularly in complex biological media like blood and serum.

Strategies for Preventing Electrode Fouling in Electrochemical Biosensors: From Materials to Clinical Applications

Abstract

Electrode fouling remains a critical challenge that compromises the accuracy, reliability, and longevity of electrochemical biosensors, particularly in complex biological media like blood and serum. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of recent scientific advances and practical strategies to mitigate fouling. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of nonspecific adsorption, showcases innovative antifouling materials such as zwitterionic peptides and engineered polymers, and details optimization techniques to enhance sensor stability. Furthermore, it critically evaluates validation protocols and performance metrics essential for translating these biosensors from research laboratories to real-world clinical, environmental, and point-of-care applications, offering researchers a structured roadmap for developing robust and fouling-resistant sensing platforms.

Understanding Electrode Fouling: Mechanisms and Impact on Biosensor Performance

In electrochemical biosensing, nonspecific adsorption (NSA) is the unintended accumulation of proteins, lipids, or other biomolecules onto an electrode surface. This phenomenon, often called "biofouling," directly passivates the electrode by forming an insulating layer that hinders electron transfer, reduces sensitivity, increases the limit of detection, and causes signal drift [1] [2]. For researchers and scientists developing robust biosensors, understanding and mitigating NSA is critical to obtaining reliable data, especially when working with complex biological samples like blood, serum, or in vivo environments [3] [2]. This guide provides troubleshooting and foundational knowledge to address this fundamental challenge.

FAQ: Understanding and Detecting Nonspecific Adsorption

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms behind nonspecific adsorption? NSA is primarily driven by a combination of physical and chemical interactions between the sensor surface and components in the sample matrix [2]. The main forces include:

- Electrostatic interactions between charged electrode surfaces and ions or charged molecules in the solution.

- Hydrophobic interactions, which are a major driving force for the adsorption of proteins and lipids.

- Hydrogen bonding and other dipole-dipole interactions.

- van der Waals forces [2]. In complex samples like serum, proteins such as albumin readily adsorb to surfaces, creating a fouling layer that can either mask the signal from the target analyte or block the bioreceptor's ability to bind its target, leading to false negatives [2].

Q2: How can I experimentally confirm that my electrode is passivated? A combination of electrochemical and physical techniques can confirm electrode passivation:

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): A significant increase in charge transfer resistance (( R_{ct} )) is a classic indicator of electrode passivation.

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): A decrease in the peak current and an increase in the peak-to-peak separation for a redox probe like ( [Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-} ) suggest a fouled surface.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): When coupled with electrochemistry (EC-SPR), this technique can directly monitor the accumulation of mass on the electrode surface in real-time, providing unambiguous evidence of fouling [2].

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for diagnosing electrode passivation:

Q3: Why does passivation cause signal drift in continuous monitoring? Signal drift occurs because NSA is often a dynamic and progressive process. As non-target molecules slowly but continuously adsorb onto the electrode surface, they create an increasing barrier to electron transfer [2]. This leads to a steadily decaying signal over time, even if the concentration of the target analyte remains constant. In in vivo sensors, this is compounded by the foreign body response, which can lead to glial cell activation and fibrotic encapsulation of the electrode [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Solutions to Prevent and Mitigate Passivation

Antifouling Materials and Coatings

A primary strategy to combat NSA is to functionalize the electrode surface with antifouling materials that create a physical and energetic barrier against non-specific interactions.

Table 1: Common Antifouling Materials for Electrochemical Biosensors

| Material Category | Examples | Mechanism of Action | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Films | Nafion [1], Zwitterionic polymers [1], Polydopamine (PDA) [1] | Creates a hydrophilic, neutral, or negatively charged barrier that resists protein adsorption. | High hydrophilicity; can be cross-linked; some (e.g., Nafion) are permselective. |

| Biomimetic Coatings | Natural cell membranes [1], Tannic acid (TA) [1], Cross-linked protein films [2] | Mimics biological surfaces to reduce recognition by fouling agents. | Good biocompatibility; can be complex to fabricate. |

| Nanoporous Layers | Silica nanoporous membrane (SNM) [1], Mesoporous gold membrane (mAu) [1] | Provides size exclusion and reduces the available surface area for fouling. | High surface area; can be tuned for specific pore sizes. |

| Hybrid Materials | CNT-conducting polymer composites [1], Peptide-based coatings [2] | Combines multiple antifouling mechanisms (e.g., conductivity and hydrophilicity). | Tunable properties; can be designed for high-performance. |

Experimental Protocol: Coating an Electrode with a Zwitterionic Polymer for Antifouling

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a robust antifouling layer using a zwitterionic polymer on a gold electrode.

Principle: Zwitterionic polymers possess both positive and negative charges, creating a highly hydrophilic surface that strongly binds water molecules. This formed hydration layer creates a physical and energetic barrier that prevents proteins from adsorbing and denaturing on the surface [1] [2].

Materials:

- Working Electrode: Gold disk electrode (2 mm diameter).

- Cleaning Reagents: Piranha solution (Caution: Highly corrosive!), absolute ethanol.

- Polymer Solution: 1 mg/mL solution of a zwitterionic polymer (e.g., poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) in deionized water.

- Cross-linker: 10 mM EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) and 5 mM NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide) in MES buffer (pH 6.0).

- Testing Solutions: 10 mM ( [Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-} ) in 1X PBS, 10% (v/v) Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) in PBS.

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish the gold electrode with 0.3 µm and 0.05 µm alumina slurry sequentially on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after each polish.

- Clean the electrode by cycling in 0.5 M ( H2SO4 ) between -0.2 V and +1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable cyclic voltammogram characteristic of a clean Au surface is obtained.

- Rinse with copious amounts of deionized water and dry under a stream of ( N_2 ) gas.

Surface Functionalization:

- Immerse the clean, dry electrode in the polymer solution for 2 hours at room temperature to allow physical adsorption.

- For a more stable covalent layer, subsequently immerse the electrode in the EDC/NHS cross-linking solution for 1 hour to activate carboxyl groups on the polymer.

- Rinse the modified electrode gently with deionized water to remove any loosely bound polymer.

Antifouling Performance Evaluation:

- Characterize the modified electrode using CV and EIS in the ( [Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-} ) solution to establish a baseline.

- Incubate the electrode in 10% FBS for 1 hour at 37°C to simulate a fouling challenge.

- Rinse the electrode with PBS and re-measure the CV and EIS in the ( [Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-} ) solution.

- A successful coating will show minimal change (< 10%) in the ( R_{ct} ) and peak current after FBS incubation compared to the baseline.

Alternative Sensing Mechanisms to Bypass Fouling

Innovative sensing mechanisms can inherently reduce the impact of fouling:

- Galvanic Redox Potentiometry (GRP): This method replaces the conventional current signal with a potential output, which is less susceptible to the resistive effects of a fouling layer [1].

- Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs): In an OECT, the sensing signal is transconductance (( g_m )), which is based on volumetric ion doping of a channel. This mechanism is less affected by surface fouling compared to traditional electrodes that rely on direct electron transfer at the surface [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Developing Antifouling Electrochemical Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrode | The foundational working electrode; offers excellent spatio-temporal resolution for in vivo studies. | Baseline electrode for neurochemical sensing (e.g., dopamine detection) [1]. |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin | A cation-exchange polymer used as an antifouling and permselective membrane. | Coating for in vivo microelectrodes to repel negatively charged interferents like ascorbic acid [1]. |

| EDC & NHS Cross-linkers | Activate carboxyl groups for covalent immobilization of biomolecules and polymers. | Creating stable, covalently bound antifouling layers (e.g., with zwitterionic polymers) [2]. |

| Zwitterionic Polymer (e.g., PSBMA) | Forms a super-hydrophilic surface that resists protein adsorption via a strong hydration layer. | Gold electrode coating for sensing in blood serum [1] [2]. |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | A complex matrix of proteins and lipids used to simulate biofouling conditions. | Standard solution for challenging and validating antifouling coatings in vitro [2]. |

| Potassium Ferrocyanide/Ferricyanide | A standard redox probe for characterizing electrode kinetics and surface fouling. | Used in CV and EIS to monitor changes in electron transfer efficiency before/after fouling challenges. |

FAQs: Understanding and Troubleshooting Electrode Fouling

FAQ 1: What are the primary causes of performance degradation in electrochemical biosensors used in complex biological fluids like blood and serum? The primary cause is electrode biofouling, a process where nonspecific substances in the sample adsorb onto the electrode surface. In serum and blood, the key interferents are proteins, lipids, and cells [4] [5]. This fouling occurs in stages: an initial layer of molecules forms instantly, followed by the main layer of foulants, which can then grow into biofilms and lead to macrofouling over days or weeks [4]. This fouling layer physically blocks the sensing pathway, passivates the electrode, and significantly reduces the sensor's accuracy, sensitivity, and functionality [6] [5].

FAQ 2: Besides fouling, what other interferents affect biosensor accuracy in these fluids? Beyond the fouling from proteins and lipids, a major class of interferents is redox-active compounds [7]. In serum, these can include endogenous molecules like ascorbate (ascorbic acid), uric acid, and acetaminophen [7]. These compounds can be oxidized or reduced at the electrode surface at similar potentials to the target analyte, generating a false current signal and leading to inaccurate measurements.

FAQ 3: What material properties are crucial for creating an antifouling sensor interface? Hydrophilicity is a key property. Research has shown that superhydrophilic surfaces create a robust hydration layer that minimizes the adhesion of biomolecules [6]. Zwitterionic materials, which contain both positive and negative charges, are also highly effective as they form strong hydration layers via electrostatic interactions, providing superior resistance to protein adsorption [8]. The three-dimensional branched architecture of dendritic zwitterionic oligopeptides can form more intramolecular hydrogen bonds, leading to a more stable hydration layer and superior antifouling capability compared to linear versions [8].

FAQ 4: My sensor works perfectly in buffer but fails in real samples. What are the first things I should check? This is a classic symptom of fouling or interference. Your troubleshooting checklist should include:

- Antifouling Coating: Does your electrode have a dedicated antifouling layer (e.g., hydrogel, zwitterionic peptide, permselective polymer)?

- Physical Barrier: For wearable sensors, have you considered a microfluidic channel to physically block contaminants from the skin? [6]

- Interferent Rejection: Does your sensor design include a permselective membrane (e.g., non-conducting polymers like poly(o-phenylenediamine)) to filter out redox-active species? [7]

- Detection Potential: Can you lower the operational potential of your sensor to avoid the oxidation window of common interferents? [7]

Comparison of Antifouling and Interference-Rejection Strategies

The table below summarizes quantitative data and key characteristics of various strategies discussed in recent literature for mitigating fouling and interference.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Antifouling and Interference-Rejection Strategies

| Strategy / Material | Key Characteristics | Target Interferents | Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superhydrophilic MOF (Cu-HHTP) [6] | Conductive metal-organic framework (MOF) with tuned hydrophilic surface. | Lipids in sweat | Prevents lipid buildup; enables accurate real-time monitoring for 24 h. |

| Double-Conductive Hydrogel (KMPPH) [5] | Hydrogel incorporating MXene and PEDOT:PSS for conductivity and stability. | Proteins, polysaccharides, lipids in serum | Low detection limit of 0.41 pg/mL for CEA in serum; good stability. |

| Dendritic Zwitterionic Oligopeptide (EK(E)CE(K)K) [8] | 3D branched peptide structure with alternating glutamic acid and lysine. | Proteins in saliva, sweat, blood | Forms 8 intramolecular H-bonds; superior hydrophilicity and stable hydration vs. linear peptides. |

| All-Electrochemical Biosensor Assembly [7] | Combines electrophoretic enzyme deposition with electrosynthesized permselective polymers. | Electroactive species (e.g., ascorbate, uric acid), proteins | Low interference bias (low µM range); successful glucose determination in untreated serum. |

| Conductive Membrane [9] | Membrane that allows analyte passage but electrochemically deactivates interferents. | Redox-active interferents | Selectively blocks redox-active interferents while allowing target analyte to pass. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol describes creating an electrode where the antifouling property is intrinsic to the sensing material.

- Key Reagent: Precursor solution of the conductive MOF Cu-HHTP (copper hexahydroxytriphenylene).

- Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean and prepare a flexible substrate suitable for your application.

- Inkjet Printing: Load the precursor solution (containing metal salts and organic ligands) into an inkjet printer.

- MOF Formation: Print the precursor solution onto the substrate. The MOF electrodes form through an in-situ self-assembly process as the solvent evaporates. This method ensures a strong bond between the MOF and the substrate.

- Mechanism of Action: The resulting Cu-HHTP electrode is superhydrophilic, exhibiting low surface energy that minimizes lipid adhesion. This prevents the formation of an inhomogeneous fouling layer, maintaining a stable current signal over time.

This protocol involves creating a separate, multifunctional hydrogel layer that provides both antifouling and conductive properties.

- Key Reagents: MXene nanosheets (conductive framework), KH570 (coupling agent), PEDOT:PSS (conductive polymer), [Ru(NH3)6]3+ (internal standard).

- Procedure:

- Synthesize MXene-COOH-Ru: Prepare single-layer MXene nanosheets via etching of Ti3AlC2. Then, carboxylate the MXene and load it with [Ru(NH3)6]3+.

- Form the Hydrogel (KMPPH): Mix the MXene-COOH-Ru complex with KH570 and PEDOT:PSS. This forms a stable, double-conductive antifouling hydrogel.

- Modify the Electrode: Cast the KMPPH hydrogel onto the surface of your electrochemical electrode (e.g., glassy carbon electrode).

- Immobilize Recognition Element: Attach the appropriate capture aptamers to the hydrogel surface for specific target detection (e.g., for carcinoembryonic antigen, CEA).

- Mechanism of Action: The hydrogel's superhydrophilicity creates a physical barrier that repels proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids. Its dual conductivity ensures efficient electron transfer, while the encapsulated [Ru(NH3)6]3+ serves as an internal standard for a ratiometric sensing strategy, correcting for background signals and instrument errors.

This protocol uses electrochemical methods to sequentially deposit a permselective polymer and immobilize enzymes, ideal for creating well-defined, miniaturized sensors.

- Key Reagents: Enzyme (e.g., Glucose Oxidase), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Glutaraldehyde (GLU), Monomer for electrosynthesis (e.g., o-phenylenediamine, pyrrole).

- Procedure:

- Electrosynthesize the Permselective Polymer: Using cyclic voltammetry (CV), electrosynthesize a non-conducting polymer (e.g., poly(o-phenylenediamine)) from its monomer directly onto the Pt working electrode surface. This forms a thin, dense film.

- Electrophoretic Protein Deposition (EPD): Place the polymer-coated electrode in a solution containing the enzyme, BSA, and GLU.

- Apply Electrical Field: Apply a pulsed current sequence. This causes the electrophoretic migration of the enzyme and BSA to the electrode surface, triggering in-situ co-crosslinking exclusively onto the electrode.

- Mechanism of Action: The electrosynthesized polymer acts as a size-exclusion and charge-selective membrane, rejecting common interferents like ascorbate and uric acid. The EPD step ensures precise spatial control of enzyme immobilization. This combined approach yields a biosensor with high enzyme loading, excellent interferent rejection, and good shelf lifetime.

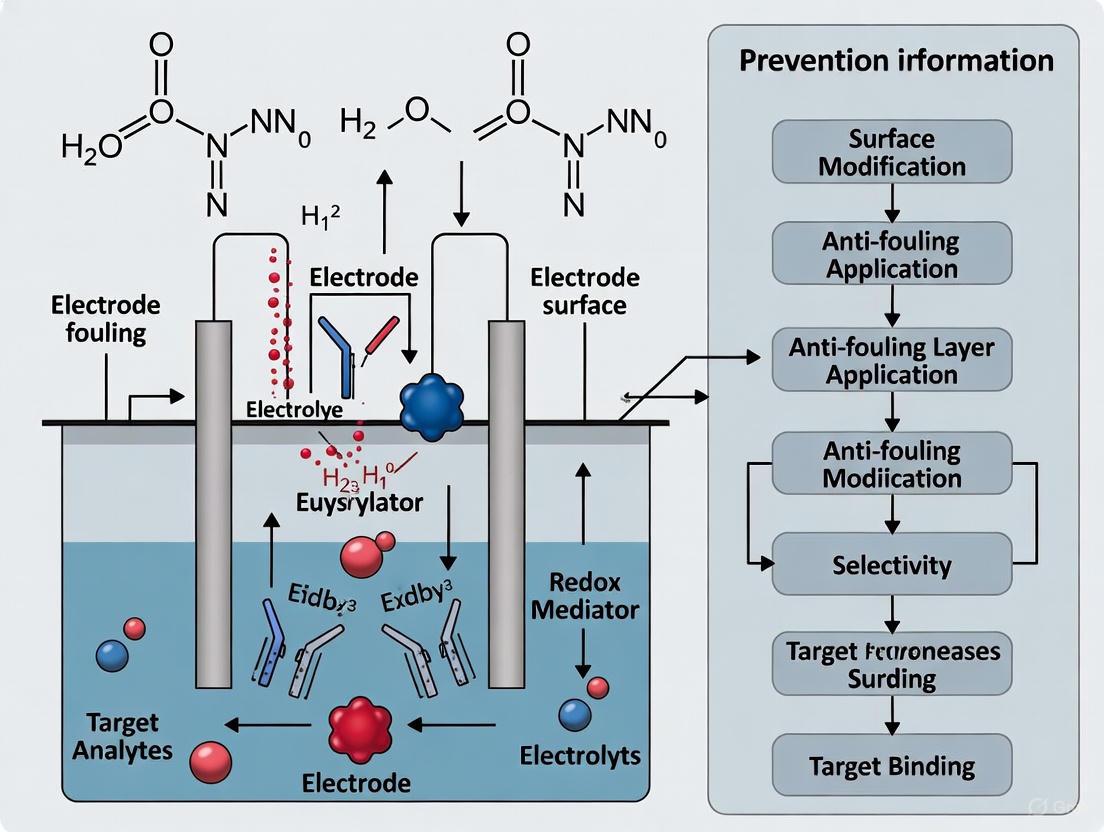

Experimental Workflow for Antifouling Biosensor Development

The following diagram illustrates a generalized logical workflow for developing and troubleshooting an electrochemical biosensor for complex fluids, integrating the strategies discussed above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Antifouling Biosensor Research

| Category | Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Materials | Conductive MOFs (e.g., Cu-HHTP) [6] | Serves as both the sensing electrode and antifouling layer via tuned superhydrophilicity. |

| MXene Nanosheets [5] | Acts as a highly conductive nanomaterial framework within hydrogels, providing large surface area. | |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS, Polyaniline) [10] [5] | Imparts electrical conductivity to hydrogels and other polymer matrices. | |

| Antifouling Polymers & Peptides | Zwitterionic Peptides (e.g., dendritic EK(E)CE(K)K) [8] | Forms a strong hydration layer via electrostatic interactions to prevent protein adsorption. |

| Non-Conducting Polymers (e.g., poly(o-phenylenediamine)) [7] | Electrosynthesized to form thin, permselective films that reject interferents. | |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) & Derivatives [5] | Traditional hydrophilic polymer used to create antifouling surfaces. | |

| Hydrogels | Double-Conductive Hydrogels (e.g., KMPPH) [5] | Combines superhydrophilic antifouling properties with high conductivity for enhanced signal. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) Hydrogel [10] | Provides a 3D antifouling interface with water retention capabilities and inherent conductivity. | |

| Assembly & Immobilization | Electrophoretic Protein Deposition (EPD) [7] | An electrochemically assisted technique for precise, spatially controlled enzyme immobilization. |

| γ-Methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (KH570) [5] | A coupling agent used to improve the stability and adhesion of materials to surfaces. |

Electrode fouling is a critical challenge in electrochemical biosensing, where the non-specific adsorption of proteins, cells, lipids, and other biomolecules onto the electrode surface occurs during exposure to complex biological fluids like blood, serum, or saliva [11] [12] [13]. This process creates an impermeable layer that degrades sensor performance by reducing sensitivity, impairing specificity, and shortening operational lifespan [12]. In blood, for instance, proteins such as human serum albumin (HSA), IgG, and fibrinogen are primarily responsible for surface fouling, leading to a drastic decrease in analytical performance [11]. Overcoming biofouling is essential for developing reliable biosensors for clinical diagnostics, therapeutic drug monitoring, and long-term implantable devices [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary consequences of electrode fouling on my electrochemical biosensor's performance?

Electrode fouling directly impacts three key performance parameters:

- Reduced Sensitivity: The fouling layer acts as a physical and chemical barrier, impeding the diffusion of the target analyte to the electrode surface and the subsequent electron transfer. This leads to a diminished electrochemical signal [12] [15].

- Loss of Specificity: Non-specific adsorption of interfering molecules can produce a false positive signal or mask the signal from the true target, leading to inaccurate readings [13].

- Shortened Sensor Lifespan: The accumulation of fouling agents can permanently deactivate the electrode's catalytic sites or immobilized bioreceptors. In implantable sensors, this is compounded by the foreign body response, which can encapsulate the device in fibrotic tissue, rendering it useless [14].

Q2: In complex biofluids like blood, which components are most responsible for fouling?

Blood is a particularly challenging matrix. The main components responsible for fouling are plasma proteins [11]:

- Human Serum Albumin (HSA): Comprises ~60% of total plasma proteins (35–50 mg mL⁻¹).

- Immunoglobulin G (IgG): Present at 6–16 mg mL⁻¹.

- Fibrinogen: Found at concentrations around 2 mg mL⁻¹. These proteins adsorb onto metallic surfaces like gold electrodes through hydrophobic interactions and electrostatic forces, forming a tenacious fouling layer [11].

Q3: My sensor signal degrades within hours in cell culture medium. What are some proven antifouling strategies I can implement?

Multiple strategies have been developed to mitigate fouling. The choice depends on your sensor design and application. The table below summarizes solutions validated in complex environments.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Antifouling Strategies for Electrochemical Sensors

| Strategy | Key Materials | Mechanism of Action | Reported Performance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Polymer Brushes | PEG/OEG, Zwitterionic polymers [11] [16] [13] | Forms a hydrated layer via steric repulsion and water binding to prevent protein adhesion [11] [12]. | Zwitterionic coatings enhance continuous sensing for therapeutic drug monitoring [16]. | PEG can be susceptible to oxidative degradation; zwitterions offer higher stability [12] [13]. |

| Protein-Based Nanocomposite | Cross-linked Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) with Gold Nanowires [14] [17] | Creates a natural physical barrier and incorporates conductive elements to maintain electron transfer [17]. | Maintains electron transfer kinetics for over one month in serum and nasopharyngeal secretions [17]. | Nozzle printing allows for precise, localized deposition on working electrodes [17]. |

| Antifouling Peptides | Self-assembled peptide nanoparticles (e.g., FFFGGGEKEKEKEK) [18] | Provides a stable, biocompatible interface resistant to non-specific adsorption and enzymatic hydrolysis [18]. | Enables accurate biomarker detection in complex biofluids [18]. | Designed for enhanced stability against proteolytic degradation in biological fluids. |

| Porous & Nanostructured Layers | Nanoporous gold, sol-gel silicate, porous emulsions [11] [12] [17] | Acts as a diffusion filter, blocking large fouling agents (proteins, cells) while allowing small analyte access [11]. | Porous gold electrodes reduce fouling; silicate sol-gel preserved signal after 6 weeks in cell culture [12]. | Porosity and thickness are critical for balancing antifouling and mass transport [17]. |

Q4: Are there any antifouling coatings that also maintain good electron transfer kinetics?

Yes, this is a key area of advancement. Conductive antifouling coatings are ideal. A prominent example is the micrometer-thick porous nanocomposite made from cross-linked BSA and gold nanowires (AuNWs) [17]. The BSA matrix provides excellent antifouling properties, while the embedded AuNWs create efficient electron transfer pathways, ensuring high sensor sensitivity even in fouling environments for extended periods [17].

Experimental Protocols for Validation and Troubleshooting

Protocol 1: Evaluating Antifouling Performance in Complex Media

This protocol is adapted from methods used to test long-term stability in biological fluids [12] [17].

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of an antifouling coating by monitoring the stability of an electrochemical signal in a complex, fouling medium over time.

Materials:

- Electrochemical workstation

- Modified working electrode (with your sensor and antifouling coating)

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) and counter electrode (e.g., Pt wire)

- Cell culture medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% FBS) or human serum/plasma

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Procedure:

- Baseline Measurement: In a clean PBS solution, perform a cyclic voltammetry (CV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurement to record the baseline signal of your redox probe or mediator.

- Incubation: Immerse the modified working electrode in the cell culture medium or serum. Maintain it at 37°C to simulate physiological conditions.

- Periodic Testing: At predetermined time points (e.g., 1h, 6h, 24h, 72h, 1 week), remove the electrode, rinse gently with PBS, and perform the same electrochemical measurement in a fresh PBS solution.

- Data Analysis: Compare the peak current (for CV) or charge transfer resistance (for EIS) at each time point to the initial baseline. A stable signal indicates effective antifouling protection, while a decaying signal indicates fouling.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of a Conductive Albumin-Based Nanocomposite Coating

This protocol summarizes the innovative method for creating a highly effective, thick antifouling coating [17].

Objective: To create a micrometer-thick, porous, and conductive antifouling coating on a gold electrode using nozzle printing.

Materials:

- Gold electrode array

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Gold Nanowires (AuNWs)

- Hexadecane (oil phase)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Glutaraldehyde (GA)

- Nozzle printer

Workflow:

- Emulsion Preparation: Create an oil-in-water emulsion by sonicating a mixture of hexadecane (oil phase) and a PBS solution containing BSA and AuNWs (water phase) for 25 minutes to form stable, nanoscale oil droplets.

- Cross-linking: Add glutaraldehyde to the emulsion immediately before printing to initiate protein cross-linking.

- Nozzle Printing: Use a nozzle printer to deposit the emulsion precisely onto the working electrode(s) of the gold array.

- Curing and Evaporation: Heat the printed electrode to complete the cross-linking of the BSA matrix and evaporate the hexadecane oil. This process results in a ~1 µm thick coating with interconnected pores and embedded AuNWs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Antifouling Electrochemical Sensor Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Antifouling Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) & Derivatives | Forms hydrophilic, steric-repulsion layers to reduce protein adsorption [11] [12]. | Creating SAMs or polymer brushes on gold electrodes. |

| Zwitterionic Compounds | Provides a super-hydrophilic surface via a tightly bound water layer, offering excellent antifouling and stability [16] [13]. | Coating for continuous sensing applications in serum [16]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Serves as a base for a biocompatible, cross-linked matrix that resists non-specific binding [14] [17]. | Key component in conductive nanocomposite coatings. |

| Gold Nanowires (AuNWs) | Integrated into non-conductive coatings to provide electrical conductivity and enhance electron transfer [17]. | Creating conductive pathways within a BSA-based coating. |

| Antifouling Peptides | Self-assemble into stable nanoparticles that create a bio-inert interface on the sensor [18]. | Forming a stable, enzyme-resistant coating for biosensors in biofluids. |

| Sol-Gel Silicate | Forms a porous, inorganic layer that acts as a physical barrier to large fouling molecules [12]. | Long-term protection of sensors in cell culture media. |

Visual Guide: Fouling Mechanisms and Antifouling Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the core problem of fouling and how different classes of antifouling strategies work to mitigate it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What are the fundamental principles behind creating an antifouling electrochemical interface? The core principles are hydrophilicity and electroneutrality [19]. A hydrophilic surface forms a strong hydration layer via hydrogen bonding with water molecules, creating a physical and energetic barrier that repels biomolecules [11] [20]. Electroneutrality prevents charged non-target molecules from being electrostatically attracted to the sensor surface, thereby avoiding nonspecific adsorption [19]. Most fouling in biological fluids is driven by hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions; these two principles directly counteract those forces [21].

Q2: My sensor's sensitivity drops significantly after testing in serum. What is the most likely cause? This is a classic symptom of biofouling. Complex biofluids like serum contain abundant proteins (e.g., human serum albumin, IgG, fibrinogen), lipids, and other biomolecules that nonspecifically adsorb onto your electrode surface [11]. This forms an impermeable layer that blocks the target analyte from reaching the electrode, reducing electron transfer and causing signal degradation [21] [20]. To confirm, try running a control experiment with a standard redox probe in buffer before and after exposure to serum.

Q3: I am using a PEG-based antifouling layer, but my sensor's performance still degrades over time. Why? While PEG is considered the "gold standard," it has limitations. PEG chains can be susceptible to oxidative damage in biochemically relevant solutions, which compromises their long-term stability [20]. Furthermore, if the surface packing density of PEG is too low or the polymer chains are too short, the coverage may be insufficient to prevent fouling effectively [20]. Consider exploring alternative materials like zwitterionic polymers, which form a more robust hydration layer and have higher oxidative stability [20].

Q4: How can I maintain good electron transfer while having a protective antifouling layer? This is a key challenge, as thick, non-conductive polymer layers can increase impedance. Here are several strategies:

- Use conductive polymers: Integrate your antifouling strategy with conducting polymers like PEDOT:PSS or polyaniline (PANI), which provide both conductivity and fouling resistance [22] [20].

- Employ nanostructured electrodes: Materials like nanoporous gold or carbon nanotubes provide a high surface area and can act as diffusion filters, excluding large fouling proteins while allowing small analytes to pass [11] [23].

- Separate recognition and readout: Perform the immunoreaction on antifouling-modified magnetic beads. After washing, the beads are brought to the electrode for signal measurement, preventing the complex sample from ever contacting the electrode [22].

Q5: The analyte I want to detect is itself a fouling agent (e.g., dopamine). What strategies can I use? When the analyte or its reaction products foul the electrode, standard barrier methods may fail. In this case, consider:

- Electrochemical activation: Applying a specific potential waveform to desorb the fouling products between measurements [12] [21].

- Catalytic redox couples: Using mediators that shuttle electrons without the analyte itself needing to be oxidized/reduced at the electrode surface [20].

- Surface modification with specific materials: Coatings like Nafion or certain carbon materials can be selected for their ability to repel the specific polymeric fouling products, such as those generated from dopamine oxidation [21].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Antifouling Interfaces

The table below summarizes key materials used to construct antifouling electrochemical biosensors, based on the principles of hydrophilicity and electroneutrality.

Table 1: Key Reagents for Constructing Antifouling Interfaces

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Antifouling Design |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Polymers | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), Oligo(ethylene glycol) (OEG) [11] [22] | Forms a hydrated layer via hydrogen bonding; steric repulsion of biomolecules. |

| Zwitterionic Materials | Phosphorylcholine (PC), Carboxybetaine (CB), Sulfobetaine (SB) [23] [20] | Creates a super-hydrophilic surface with a strong bound water layer; electrically neutral. |

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polyaniline (PANI) [22] [20] | Provides electrical conductivity while can be engineered with antifouling properties. |

| Hydrogels | Chitosan hydrogel, DNA hydrogel, Peptide hydrogel [22] [19] | Highly hydrated 3D network that acts as a physical and chemical barrier to fouling agents. |

| Nanostructured Materials | Nanoporous gold, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [11] [23] | Acts as a size-exclusion diffusion filter; high surface area can improve sensitivity. |

| Stable Surface Linkers | Pt-S interaction (vs. traditional Au-S) [24] | Provides a more robust anchor for biorecognition elements in complex biological fluids. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Constructing a Chitosan-DNA Dual-Network Hydrogel Biosensor

This protocol details the creation of a bifunctional hydrogel that combines antifouling properties with biomolecular recognition for detecting targets like ATP in complex biofluids [19].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Chitosan (CS)

- Epichlorohydrin (ECH)

- DNA strands (Y1, Y2, Y3) and ATP-specific aptamer Linker DNA

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl) and Sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

2. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Preparation of Y-DNA Scaffold

- Mix DNA strands Y1, Y2, and Y3 in a 1:1:1 ratio to a final concentration of 10 µM.

- Heat the mixture to 95 °C for 5 minutes to denature the DNA.

- Slowly cool the solution to room temperature to allow the self-assembly of the Y-DNA scaffold [19].

- Step 2: Electrochemical Deposition of Chitosan Hydrogel

- Prepare a 1.2 wt% CS solution dissolved in 0.46% (v/w) HCl.

- Add NaOH to a final concentration of 0.06 M and ECH to 0.04 M to the CS solution under stirring.

- Transfer the mixture to an electrochemical cell with a GCE as the working electrode.

- Apply a constant potential of -2.0 V for 120 seconds to deposit the CS hydrogel onto the GCE (CS/GCE) [19].

- Step 3: Assembly of the DNA Network

- Dropcast the prepared Y-DNA scaffold solution onto the CS/GCE surface.

- Incubate to allow the Y-DNA to attach to the CS hydrogel via electrostatic interactions and physical entanglement.

- Subsequently, introduce the Linker DNA (with the ATP aptamer) to hybridize with the Y-DNA scaffold, forming the final CS-DNA dual-network hydrogel [19].

- Step 4: Electrochemical Measurement

- Use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) to measure the signal change upon ATP binding.

- The sensor can be tested in complex media like undiluted human serum to validate its antifouling performance [19].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the structure of the resulting dual-network hydrogel:

Protocol 2: Fabricating a Pt-S Bond-Based Stable Antifouling Interface

This protocol describes an immobilization strategy using a robust Pt-S bond to anchor antifouling peptides, offering superior stability over conventional Au-S bonds [24].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Platinum Nanoparticles (PtNP)

- Trifunctionalized Branched-Cyclopeptide (TBCP)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

2. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Surface Preparation with PtNPs

- Deposit platinum nanoparticles onto the clean electrode surface to serve as the platform for Pt-S bond formation [24].

- Step 2: Immobilization via Pt-S Bond

- Incubate the PtNP-modified electrode with the thiol-containing TBCP solution.

- The strong Pt-S bond forms spontaneously, securely anchoring the peptide to the surface. Electrochemical and DFT studies confirm the superior stability of Pt-S compared to Au-S bonds [24].

- Step 3: Validation of Antifouling and Stability

- Test the antifouling performance by exposing the modified electrode to undiluted human serum and monitoring the signal.

- For stability tests, perform electrochemical desorption experiments in KOH or monitor signal retention over several weeks. Electrodes with Pt-S bonds have demonstrated less than 10% signal degradation over 8 weeks [24].

Performance Data & Material Comparisons

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Antifouling Material Performance

| Antifouling Material / Strategy | Tested Medium | Key Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pt-S Bond with TBCP Peptide [24] | Undiluted human serum | Signal stability over 8 weeks | < 10 % signal degradation |

| Silicate Sol-Gel Layer [12] | Cell culture medium | Long-term signal stability | Signal still detectable after 6 weeks of incubation |

| Poly-l-lactic Acid (PLLA) [12] | Cell culture medium | Short to mid-term protection | Complete signal deterioration after 72 hours |

| PEGylated Polyaniline Nanofibers [20] | Undiluted human serum | Signal retention after incubation | Retained 92.17% of initial current |

| PEDOT:PSS Sensor for TCP [20] | Gaseous TCP / Cresol products | Signal retention after 20 repetitive measurements | 85% of initial current retained (vs. 30% for bare GCE) |

| Magnetic Bead-based Assay [22] | Complex serum | Limit of Detection (LOD) for h-IgG | 6.31 ag mL⁻¹ (0.04 zeptomoles mL⁻¹) |

Table 3: Advantages and Limitations of Common Antifouling Strategies

| Strategy | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PEG & Derivatives [22] [20] | "Gold standard", well-understood, commercially available. | Susceptible to oxidative degradation; can increase impedance. |

| Zwitterionic Polymers [23] [20] | Strong hydration, high oxidative stability, low immunogenicity. | Can be challenging to graft; may require complex synthesis. |

| Hydrogels [22] [19] | High hydration, 3D structure for high probe loading. | May slow diffusion kinetics; mechanical stability can vary. |

| Nanostructured Electrodes [11] | Size-exclusion filtering, high surface area for sensitivity. | Fabrication complexity; pore size must be carefully controlled. |

| Magnetic Bead Separation [22] | Excellent fouling resistance; pre-concentration of analyte. | Multi-step process; requires additional equipment (magnet). |

| Pt-S Bond Stabilization [24] | Exceptional interfacial stability in complex fluids. | Cost of Pt nanoparticles; less established than Au-S chemistry. |

Innovative Antifouling Materials and Surface Modification Strategies

FAQs: Core Design Principles and Selection

Q1: What are the fundamental design principles behind EK and DK zwitterionic peptides? The core principle is to create a molecular structure with a balanced distribution of positively and negatively charged groups. EK peptides are composed of alternating glutamic acid (E, negatively charged) and lysine (K, positively charged) residues. Similarly, DK peptides use aspartic acid (D) and lysine (K). This arrangement creates a dense, uniform hydration layer via strong water dipole interactions, which forms a physical and energetic barrier that repels biomolecules and prevents nonspecific adsorption [25] [26]. The sequence is typically designed with a terminal cysteine (C) to provide a thiol group for stable anchoring to gold surfaces [26].

Q2: In what scenarios is a dendritic or arched-peptide (APEP) design superior to a linear one? A dendritic design is superior in dynamic, complex biological fluids like blood, saliva, or sweat where stability under flow and shear stress is critical. While linear peptides (e.g., CEKEKEK) can be conformationally flexible, exposing hydrophobic peptide backbones and leading to an unstable hydration layer [8], dendritic peptides (e.g., EK(E)CE(K)K) feature a three-dimensional branched architecture. This structure forms significantly more intramolecular hydrogen bonds, leading to lower dipole moments, higher conformational stability, and a more robust, stronger hydration layer that resists displacement [8].

Q3: How can I enhance the stability and antifouling performance of my designed zwitterionic peptide? Two advanced strategies are effective:

- Incorporating D-Amino Acids: Designing peptides with D-amino acids, such as D-diaminopropionic acid (D-Dap), makes them unrecognizable to natural proteases. This confers robust stability against enzymatic hydrolysis in biofluids, enabling long-term operation (e.g., over 3 weeks in serum) without performance degradation [27].

- Optimizing Spacer Length: Adjusting the distance between the adjacent amino and carboxyl groups can fine-tune the peptide's hydrophilicity and rigidity. Shorter spacers can enhance superhydrophilicity and structural rigidity, leading to superior antifouling performance [27].

Q4: My biosensor's sensitivity drops in serum. Is this a fouling issue, and how can peptides help? Yes, a sensitivity drop in complex media like serum is typically caused by biofouling. Proteins, lipids, and other biomolecules nonspecifically adsorb onto the electrode surface, creating an impermeable layer that blocks electron transfer and increases background noise [12] [20]. Zwitterionic peptides form a protective barrier that prevents this adsorption, thereby preserving the sensor's sensitivity and accuracy, allowing for reliable detection of low-concentration biomarkers in undiluted serum [27] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Antifouling Performance in Complex Fluids

| Observed Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High nonspecific adsorption in serum or blood. | Low surface grafting density of the peptide [29]. | Optimize peptide concentration and immobilization time to achieve a dense, tightly packed monolayer. |

| Signal drift in sweat or saliva. | Unstable hydration layer of linear peptides under dynamic conditions [8]. | Redesign the peptide to a dendritic or arched structure (e.g., EK(E)CE(K)K) to enhance conformational stability and hydration layer strength [8]. |

| Rapid performance degradation over time. | Proteolytic cleavage of the peptide by enzymes in the biofluid [27]. | Synthesize peptides using D-amino acids (e.g., D-Dap) to create a protease-resistant sequence [27]. |

| Increased impedance and loss of sensitivity. | The antifouling layer is too thick or non-conductive. | Integrate the peptide with a conducting polymer (e.g., PEDOT) where the peptide acts as a dopant, combining antifouling properties with electrical conductivity [28]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Sensor Fabrication and Results

| Observed Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irregular or weak electrode attachment. | Unreliable thiol-gold chemistry for peptide anchoring. | Ensure the peptide sequence includes a terminal cysteine (C) residue and that the gold electrode surface is impeccably clean before immersion [26]. |

| Poor orientation of the peptide layer. | The anchoring group is not positioned correctly within the sequence. | Place the cysteine anchor at the terminus of the sequence, using a spacer (e.g., GGC) to ensure the EK/DK chain is properly exposed to the solution [26]. |

| Failure to integrate with a biorecognition element. | The peptide lacks a functional group for probe immobilization. | Design a multifunctional peptide that includes a specific "linking" segment (e.g., a short sequence with carboxyl groups) for covalent attachment of antibodies or aptamers [28]. |

Protocol 1: Fabricating a Dendritic ZIP-Modified Gold Electrode

This protocol details the creation of a highly stable antifouling surface based on dendritic zwitterionic oligopeptides (e.g., EK(E)CE(K)K) for detection in complex fluids [8].

- Electrode Preparation: Clean a gold electrode with piranha solution (Caution: Highly corrosive), followed by sequential sonication in ethanol and deionized water. Dry under a nitrogen stream.

- Peptide Immobilization: Incubate the clean gold electrode in a 1.0 mg/mL solution of the synthesized dendritic ZIP (e.g., EK(E)CE(K)K) in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 12 hours at 4°C.

- Rinsing and Drying: Gently rinse the modified electrode with copious amounts of phosphate buffer to remove physically adsorbed peptides. Dry with nitrogen.

- Characterization: Use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution to confirm monolayer formation. A successful modification will show a significant increase in electron-transfer resistance.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Antifouling Performance in Human Serum

This method tests the fabricated sensor's resistance to fouling in a clinically relevant matrix [27].

- Baseline Measurement: Record the electrochemical signal (e.g., CV or EIS) of the biosensor in a clean buffer solution.

- Exposure to Serum: Incubate the biosensor in 100% undiluted human serum at 37°C for a predetermined period (e.g., 1 hour, 24 hours, 1 week).

- Post-Incubation Measurement: After incubation, rinse the sensor thoroughly with buffer and measure the signal again in the clean buffer solution.

- Analysis: Calculate the signal retention percentage. A high-performance antifouling surface should retain >90% of its original signal even after prolonged exposure [27].

Table 1: Comparative performance of different zwitterionic peptide designs in complex biofluids.

| Peptide Type | Example Sequence | Test Medium | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear EK | CEKEKEK | Human saliva, sweat, blood | Baseline antifouling performance | [8] |

| Dendritic/Arched EK | EK(E)CE(K)K | Human saliva, sweat, blood | Superior hydrophilicity and antifouling vs. linear CEKEKEK | [8] |

| Long Linear EK | EKEKEKEKEKGGC | GI fluid, bacterial lysate | Outperformed conventional PEG coatings | [26] |

| DK with D-amino acids | CPPPP(D-Dap)₄ | Human serum | Stable detection for 3+ weeks; LOD for cortisol: 3.5 pg/mL | [27] |

| Multifunctional Peptide | Custom sequence with anchoring/doping/linking/antifouling parts | Human serum | Retained antifouling capability for 20 days; LOD: 2.3 fM | [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for developing zwitterionic peptide-based biosensors.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Fmoc-Protected Amino Acids | Building blocks for peptide synthesis. Includes Fmoc-Lys(Boc)-OH, Fmoc-Glu(OtBu)-OH, Fmoc-Asp(OtBu)-OH, and Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-OH. | Solid-phase peptide synthesis of designed EK, DK, or APEP sequences [25]. |

| Gold Electrodes/Substrates | The transducer surface for the biosensor. Provides a platform for covalent attachment of thiolated peptides. | Used as the base electrode for creating the self-assembled peptide monolayer [8] [26]. |

| Porous Silicon (PSi) Substrates | A high-surface-area substrate for label-free optical biosensing. | Functionalized with EK peptides (e.g., EKEKEKEKEKGGC) to create antifouling aptasensors for protein detection [26]. |

| Conducting Polymer (PEDOT) | A conductive matrix to maintain electrode sensitivity when coated with non-conductive layers. | Multifunctional peptides with negative "doping sequences" are electropolymerized into PEDOT to form a stable, conductive, and antifouling substrate [28]. |

| Syringaldazine | A model redox mediator adsorbed on carbon electrodes to test the protective effect of antifouling layers. | Used to evaluate the integrity of various antifouling coatings by monitoring the stability of its electrochemical signal in complex media [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are multifunctional probes in electrochemical biosensing, and why are they important? Multifunctional probes are single molecules, such as engineered peptides, designed to perform multiple tasks simultaneously on an electrode surface. They typically integrate a specific biorecognition element (like an aptamer) with antifouling sequences (like zwitterionic peptides) and sometimes additional functions like antibacterial properties. They are crucial for enabling direct, accurate, and stable sensing in complex biological media (e.g., blood, saliva) by preventing the non-specific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules that foul the electrode and degrade sensor performance [11] [30] [31].

Q2: I've synthesized a branched peptide probe with antifouling and recognition sequences, but my electrochemical signal is low. What could be wrong? Low signal can arise from several issues. Here is a structured guide to troubleshoot this problem:

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Electrode Conductivity | Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in a standard redox probe solution (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). A high charge-transfer resistance indicates a problem. | Ensure conductive underlayers like PEDOT:PSS or gold nanoparticles are properly deposited to facilitate electron transfer [30]. |

| Probe Orientation/Assembly | Use surface characterization techniques like X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) or quartz crystal microbalance (QCM-D). | Optimize the surface functionalization protocol. For gold electrodes, use a thiolated anchor; ensure the probe is not denaturing upon attachment [30] [12]. |

| Inefficient Target Binding | Test the sensor in a buffer containing only the target analyte. If the signal remains low, the recognition sequence may be sterically blocked. | Re-evaluate the probe design. The linker between the antifouling and recognition domains may need optimization to ensure the aptamer is accessible [30]. |

Q3: My biosensor works well in buffer but fails in real samples like serum or saliva. The signal drops and becomes unstable. What should I do? This is a classic symptom of biofouling or non-specific adsorption that your antifouling moiety is failing to suppress.

- Verify Antifouling Performance: Use a technique like QCM-D or laser scanning confocal microscopy with fluorescently labeled proteins to directly quantify and visualize non-specific adsorption on your modified surface. One study showed that a well-designed zwitterionic peptide layer could reduce non-specific protein adsorption to negligible levels [30].

- Check the Integrity of the Antifouling Layer: Ensure your antifouling sequences (e.g., EKEKEKEK) form a dense, well-ordered layer. Incomplete coverage will leave exposed sites for fouling. The hydration layer formed by these groups is critical for repelling biomolecules [30] [31].

- Consider an Integrated Antibacterial Function: In long-term measurements, even minimal bacterial adsorption can form biofilms. Incorporating an antibacterial peptide sequence (e.g., KWKWKWKW) into your multifunctional probe can mitigate this [30].

Q4: How can I quantitatively compare the effectiveness of different antifouling materials for my sensor? You can compare different coatings by measuring key electrochemical parameters before and after exposure to a fouling solution (e.g., serum, cell culture medium). The table below summarizes metrics from a study that evaluated over 10 antifouling layers [12]:

| Antifouling Material | Key Characteristic | Signal Preservation After Fouling (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Silicate Sol-Gel | Porous, high mechanical stability | Signal halved in 3 hours, but still detectable after 6 weeks [12] |

| Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) | Porous polymer | Low signal change initially; complete deterioration after 72 hours [12] |

| Poly(L-lysine)-g-PEG | Hydrophilic, forms hydration layer | Sustained catalyst performance during prolonged incubation [12] |

| Zwitterionic Peptide | Electroneutral, highly hydrophilic | Effective resistance to biomolecule adhesion in complex media [30] |

Q5: I'm observing strange peaks and a shifting baseline in my cyclic voltammograms. Are these related to my probe? While your probe or its interaction with the target could cause peaks, unusual voltammograms often point to experimental setup issues. Before blaming your chemistry, rule out these common problems [32]:

- Unexpected Peaks: Can be caused by impurities in your electrolyte, solvent, or from electrode degradation. Always run a "background" scan with just the electrolyte.

- Unstable or Hysteretic Baseline: Often due to high charging currents, which can be worsened by a faulty working electrode or high scan rates. Try reducing the scan rate.

- pH Drift: Can cause shifting signals. Ensure your buffer has sufficient capacity and that the reference electrode junction is not clogged [33]. Follow a systematic troubleshooting procedure to check your potentiostat, cables, and electrodes [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Fixing Signal Loss in Complex Media

Problem: A significant drop in sensor response (current, potential shift) when moving from buffer to a complex biological sample.

Investigation Protocol:

- Confirm Fouling: Use a non-faradaic (label-free) method like EIS to track the increase in charge-transfer resistance (Rct) over time as the sensor is exposed to the sample. A rising Rct indicates fouling.

- Check Sensor Surface: After testing, gently rinse the electrode and perform a cyclic voltammetry scan in a clean redox probe solution. A distorted or suppressed signal compared to a pristine sensor confirms fouling.

- Identify the Weakness:

- Test Antifouling Layer Alone: Immobilize only the antifouling part of your probe (e.g., the EKEKEKEK sequence) and expose it to the sample. Use QCM-D to see if proteins adsorb. If they do, your antifouling chemistry needs optimization [30].

- Test Recognition Layer Alone: Immobilize the recognition element (e.g., aptamer) on the electrode without the antifouling moiety. Exposure to a sample containing non-target proteins will show if the recognizer itself is prone to non-specific adsorption.

Solutions:

- Optimize Probe Packing Density: A low density of antifouling molecules leaves gaps. Optimize your immobilization conditions (concentration, time) to form a dense, ordered monolayer [11].

- Switch Antifouling Chemistry: If PEG-based sequences are ineffective, try zwitterionic peptides or hydrogels, which can form a more robust hydration layer [31].

- Separate Recognition and Readout: Implement a magnetic bead-based assay. The immunorecognition occurs on antifouling-coated beads, which are then washed clean of contaminants before being brought to the electrode for measurement. This physically prevents the electrode from being fouled [31].

Guide 2: Resolving Inconsistent Performance Between Sensor Batches

Problem: Sensors fabricated in different batches show large variations in sensitivity and baseline signals.

Investigation Protocol:

- Standardize Electrode Pre-treatment: Inconsistencies often start here. Implement a strict, documented protocol for electrode polishing (e.g., specific grits of alumina slurry, sonication time) and cleaning (electrochemical cycling in H₂SO₄ for Pt or Au electrodes) [32].

- Characterize Each Batch: Use a standard redox couple like potassium ferricyanide to calculate the electroactive surface area for a sample from each batch. Significant variation points to inconsistent electrode preparation or modification.

- Monitor Modification Steps: Use techniques like EIS or CV after each modification step (conductive polymer deposition, nanoparticle attachment, probe immobilization) to ensure consistent changes in electrochemical properties across batches.

Solutions:

- Control Probe Purity and Concentration: Use high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-purified peptides and accurately quantify the stock solution before immobilization.

- Automate Modification: Where possible, use automated pipetting or electrochemical deposition to ensure consistent reaction times and reagent volumes across all electrodes.

- Implement Quality Control (QC): Establish pass/fail criteria based on the electroactive surface area or baseline impedance. Discard batches that fall outside the acceptable range.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Low-Fouling Electrochemical Biosensor Based on Multifunctional Branched Peptides

This protocol details the construction of a biosensor for detecting the SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein in saliva, as described in the research [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Solution | Conductive polymer layer; enhances electron transfer and provides a substrate for nanoparticle adhesion [30]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Increase surface area and facilitate electron transfer; provide a surface for thiol-based chemistry to anchor the probe [30]. |

| Multifunctional Branched Peptide (PEP) | Core sensing element. Contains: 1) Zwitterionic antifouling sequence (EKEKEKEK), 2) Antibacterial sequence (KWKWKWKW), 3) Specific recognition aptamer (KSYRLWVNLGMVL) [30]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard buffer for washing steps and as a medium for electrochemical measurements. |

| Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD) Protein | The target analyte, used for testing sensor performance. |

Methodology:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) sequentially with 0.3 µm and 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a polishing pad.

- Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water and dry [30].

Deposition of Conductive Polymer:

- Immerse the bare GCE in a 5 mL aqueous solution containing 7.4 mM EDOT and 1.0 mg mL⁻¹ PSS.

- Electrodeposit the PEDOT:PSS layer onto the GCE using chronoamperometry or cyclic voltammetry according to established protocols [30].

Electrodeposition of Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs):

- Place the PEDOT:PSS-modified electrode in a solution of HAuCl₄.

- Use amperometry to deposit AuNPs, creating a uniform, nano-structured surface [30].

Immobilization of Multifunctional Peptide:

- Incubate the AuNP/PEDOT:PSS electrode in a solution of the thiolated branched peptide (PEP).

- Allow the peptide to self-assemble onto the gold surface via gold-sulfur (Au-S) bonds for several hours.

- Rinse the electrode with PBS to remove physically adsorbed peptides [30].

Antifouling and Antibacterial Validation:

- Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM-D): Immerse a peptide-coated quartz crystal in serum or saliva and monitor the frequency shift. A minimal shift indicates effective resistance to non-specific adsorption [30].

- Laser Confocal Microscopy: Incubate the modified surface with fluorescently labeled proteins or bacteria. Effective antifouling/antibacterial layers will show little to no fluorescence [30].

Electrochemical Detection:

- Use the modified electrode as the working electrode in a standard three-electrode cell.

- Perform electrochemical measurements (e.g., EIS, DPV) after incubating the sensor with the sample containing the target RBD protein.

- The binding event will cause a measurable change in current or impedance, proportional to the target concentration [30].

Workflow Diagram: Biosensor Fabrication and Sensing

Diagram: Multifunctional Branched Peptide Design

## Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My polydopamine-coated electrode shows a significant drop in sensitivity and high background noise. What could be the cause?

This issue is frequently caused by non-specific adsorption (NSA) or suboptimal coating properties. The table below outlines common causes and solutions.

| Problem & Symptoms | Likely Causes | Verified Solutions & References |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Signal & Signal Drift• Drifting baseline in measurements• Reduced signal-to-noise ratio• False positive readings | • NSA of proteins from complex samples (e.g., serum).• Incomplete surface coverage of antifouling coating.• Too thick a PDA layer, hindering electron transfer. | • Employ co-deposition: Electrochemically co-deposit PDA with hyaluronic acid (HA) to create a highly hydrophilic, fouling-resistant layer [34].• Use zwitterionic polymers: Graft sulfobetaine polymer (PSB) via a PDA anchor to form an ultralow fouling surface [35].• Incorporate ethanolamine: Use a one-step electrosynthesis of PDA with ethanolamine (ETA) to incorporate fouling-resistant hydroxyl groups [36]. |

| Poor Permeation or Flux• Greatly reduced pure water flux in filtration membranes.• Low analyte signal. | • Pore blockage from overgrowth of the PDA layer.• Excessive deposition time or dopamine concentration. | • Optimize deposition time: Limit polymerization time to prevent overgrowth. A study showed extended dipping in Tris buffer led to PDA partly covering surface pores [37].• Optimize dopamine concentration: Higher dopamine concentrations (>2 g/L) can lead to thicker, less permeable coatings [38]. |

| Low Coating Stability• Coating delaminates during flow assays or long-term immersion. | • Weak adhesion of the secondary antifouling layer.• Insufficient polymerization. | • Choose co-deposition over post-modification: The PDA-PSB co-deposition method demonstrated superior stability in vitro compared to PSB grafted alone [35].• Ensure proper electrochemical parameters: Use a constant potential of 1 V (vs. SCE) for 30-60 minutes in a solution of 10 mM DA and 2 mg/mL HA in PBS (pH 6) for robust co-deposition [34]. |

| Inefficient Analyte Recognition• Good antifouling but poor specific signal.• Low bioreceptor activity. | • Denaturation of immobilized bioreceptors (e.g., antibodies).• Steric hindrance from the coating. | • Utilize one-step functionalization: The ePDA-ETA film provides a biocompatible interface that facilitates proper IgG immobilization and improves antibody-antigen affinity [36]. |

Q2: How can I make my polydopamine coating more resistant to fouling from blood serum?

For applications in complex matrices like blood serum, simple PDA coatings may be insufficient. The most effective strategies involve incorporating highly hydrophilic molecules:

- Co-deposition with Hyaluronic Acid (HA): Electrochemical co-deposition of PDA/HA creates a surface that significantly resists non-specific protein adsorption and fibroblast adhesion. This is due to HA's strong water retention capability, forming a protective hydration layer [34].

- Grafting Zwitterionic Polymers: Zwitterionic materials, such as polysulfobetaine (PSB), are superior to traditional PEG in resisting protein adsorption. A PDA-PSB co-deposited coating has been shown to significantly reduce inflammatory cell recruitment and glial scar formation around neural implants in vivo [35].

- One-Pot Synthesis with Ethanolamine: Electropolymerizing dopamine in the presence of ethanolamine (ETA) incorporates ETA into the polymer matrix. The resulting ePDA-ETA film is rich in hydroxyl groups, which provide intrinsic anti-fouling properties while offering sites for bioreceptor immobilization [36].

## Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electrochemical Co-deposition of Polydopamine/Hyaluronic Acid (PDA/HA)

This protocol describes a simple method to create an anti-biofouling coating on conductive electrodes [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function / Role |

|---|---|

| Dopamine Hydrochloride | Polymerizable monomer for forming the adhesive PDA base layer. |

| Hyaluronic Acid (HA) | High molecular weight polysaccharide that provides hydrophilicity and fouling resistance. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 6 | Electrolyte solution for the polymerization reaction. |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) or Gold Electrodes | Conductive substrate for the bioelectrode. |

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Freshly prepare a polymerization solution containing 10 mM dopamine hydrochloride and 2 mg/mL hyaluronic acid in PBS (pH 6).

- Electrode Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system with the target electrode (e.g., ITO) as the working electrode, a Pt wire as the counter electrode, and a standard calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference.

- Electrochemical Deposition: Perform the deposition by applying a constant potential of 1.0 V (vs. SCE) to the working electrode for 30 to 60 minutes.

- Post-treatment: After coating, gently wash the modified electrode with copious amounts of deionized water to remove any loosely bound molecules and store in PBS (pH 7.4) until use.

Protocol 2: Two-Step Dopamine-to-Polydopamine Modification for Membranes

This protocol is highly effective for modifying polymer membranes (e.g., PES) to enhance fouling resistance and UV stability [37].

Methodology:

- Membrane Fabrication with Dopamine Additive: Prepare a polymer dope solution (e.g., 17.5% PES in NMP) and add a defined concentration of dopamine hydrochloride (0.5-4%) as an additive. Cast the membrane using the phase inversion technique.

- Alkaline-induced Polymerization: Immerse the as-cast membrane (now containing embedded dopamine) into an alkaline Tris-HCl buffer solution (pH 8.5). The dipping duration (e.g., 5 to 36 hours) controls the extent of dopamine polymerization into polydopamine within the membrane matrix.

- Key Control Parameter: The concentration of dopamine in the first step and the polymerization time in the second step are critical. Higher dopamine loadings and extended polymerization times improve hydrophilicity and antifouling but can lead to pore blockage and reduced flux [37].

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the fundamental mechanism by which polydopamine and other coatings prevent fouling? A: Fouling occurs via hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic forces, and hydrogen bonding between the surface and proteins/cells. Polydopamine itself is hydrophilic, which helps reduce fouling by hydrophobic foulants like oil [38]. However, its intrinsic adhesiveness can be a drawback. Advanced coatings like zwitterionic polymers and HA work by forming a tight hydration layer via water solvation of their charged or polar groups. This physical barrier of water molecules effectively prevents proteins from adhering to the surface [35].

Q: My research involves implantable biosensors. Which coating is best for reducing the foreign body response? A: For implantable devices, the co-deposition of PDA with a zwitterionic polymer like polysulfobetaine (PSB) has shown exceptional results in vivo. This coating significantly reduces the adsorption of pro-inflammatory serum proteins, which in turn minimizes the recruitment and activation of microglia and macrophages. This leads to a substantial reduction in glial scar formation around the implant, which is crucial for maintaining long-term signal quality [35].

Q: How does the electrochemical deposition of PDA compare to simple solution-based immersion? A: Electrochemical deposition provides superior control over the polymerization process. It generates the reactive quinone species directly at the electrode surface, leading to more homogeneous, thinner, and better-adhered films with improved electrochemical properties. In contrast, solution-based immersion (in Tris buffer, pH 8.5) can result in heterogeneous coatings, faster deposition, and the formation of PDA aggregates in solution, which may physically block membrane pores or create a rougher surface [36].

Q: Can I use polydopamine to immobilize my specific bioreceptor (e.g., an antibody)? A: Yes, this is one of the key advantages of PDA. The quinone groups in the polymer readily react with nucleophiles like the amine groups present in antibodies, enzymes, or other proteins via Michael addition or Schiff base reactions. This allows for a robust, covalent immobilization of bioreceptors without the need for additional coupling chemicals like EDC/NHS, making it a versatile platform for biosensing [36] [39].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of electrode fouling in electrochemical biosensors, and why is it a critical issue? Electrode fouling occurs due to the nonspecific adsorption of biomolecules (such as proteins, peptides, and carbohydrates) present in complex biological fluids like blood, serum, or saliva onto the sensor surface. [40] This accumulation forms an impermeable layer that reduces the sensor's sensitivity, selectivity, and response time, increases background noise, and ultimately shortens the sensor's operational lifespan. [40] This is a critical barrier, especially for implantable sensors or those designed for continuous monitoring, as fouling leads to false signals and unreliable data. [40]

Q2: How do gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) contribute to antifouling and sensor performance? Gold nanoparticles enhance biosensors through several mechanisms. They provide a high electrocatalytic activity that improves the electron transfer rate and signal sensitivity. [41] Their high surface-area-to-volume ratio allows for a greater loading of recognition elements (like antibodies or aptamers). To confer antifouling properties, AuNPs are often coated with protective layers such as polyethene glycol (PEG) or zwitterionic polymers, which form a hydrophilic barrier that repels protein adsorption. [40]

Q3: What role do conductive polymers, like polyaniline (PANI), play in preventing fouling? Conductive polymers are valuable for constructing stable, antifouling biosensors. [42] For instance, polyaniline (PANI) hydrogels possess a three-dimensional structure and excellent water retention capabilities, which help prevent nonspecific adsorption. [10] PANI can also be used as a scaffold for the immobilization of other antifouling materials, such as specially designed peptides, combining its conductive properties with superior fouling resistance. [42]

Q4: Are there fully synthetic alternatives to biological recognition elements that resist fouling? Yes, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic polymers with cavities tailored to a specific target molecule. They are robust, cost-effective, and exhibit good reproducibility in complex matrices. [43] When designed with hydrophilic and electrically neutral properties, they can inherently resist nonspecific protein adsorption, making them an excellent antifouling recognition element. [43]

Q5: What are the latest advancements in peptide-based antifouling coatings? Recent research has moved beyond simple linear peptides to more sophisticated architectures. For example, dendritic zwitterionic oligopeptides with a three-dimensional branched structure have demonstrated superior antifouling capability compared to linear versions. [8] Their stable conformation forms a stronger hydration layer via ionic solvation, effectively resisting adsorption in diverse fluids like saliva, sweat, and blood. [8] Another innovation is the arched-peptide (APEP), which incorporates a serine residue and is immobilized at both ends, forming a stable arch structure that enhances stability against proteolytic hydrolysis and improves antifouling performance. [42]

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Complex Samples

A poor signal-to-noise ratio often results from inadequate antifouling protection, leading to nonspecific adsorption.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient antifouling layer | Test sensor response in a pure buffer vs. spiked complex fluid (e.g., 10% serum). A significant signal drop in serum indicates fouling. | Incorporate a dense, hydrophilic antifouling layer. Use dendritic zwitterionic oligopeptides [8] or modify surfaces with PEG [40]. |

| Non-optimized electrode coating | Use Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to monitor layer-by-layer assembly. A large, unstable charge transfer resistance suggests uneven coating. | Employ controlled deposition methods like electro-polymerization for polymers [42] or ensure homogeneous nanomaterial dispersion to avoid "coffee-ring" effects [43]. |

| Interference from electroactive species | Perform a control experiment with the sample without the target analyte. Observed currents indicate interference. | Use selective recognition elements (e.g., aptamers [43]) and voltammetric techniques like DPV or SWV that minimize background current [41]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Antifouling Performance with EIS

- Preparation: Prepare a 5 mM solution of (\ce{[Fe(CN)6]^{3-/4-}}) in a neutral pH buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Baseline Measurement: Record a CV or EIS spectrum of the bare or modified electrode in the probe solution.

- Challenge Test: Immerse the sensor in a challenging biological fluid (e.g., undiluted human serum or plasma) for 15-30 minutes.

- Rinsing: Gently rinse the electrode with deionized water to remove loosely adsorbed species.

- Post-Test Measurement: Record the CV/EIS again in the pristine probe solution.

- Analysis: Compare the charge transfer resistance (Rct) or peak current before and after the challenge. A minimal change (e.g., < 10%) indicates excellent antifouling performance.

Guide 2: Solving Sensor Signal Instability and Degradation

Signal drift and degradation can stem from the physical desorption of materials or enzymatic breakdown.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable immobilization of biorecognition element | Monitor the sensor's baseline signal over multiple cycles in a buffer. A steadily drifting baseline suggests leaching. | Use a covalent immobilization strategy. For peptides, employ cysteine anchors to gold surfaces or use coupling chemistry to PANI films [42]. |

| Enzymatic degradation of probes | Incubate the modified electrode in a solution containing nucleases (for DNA aptamers) or proteases (for peptides) and measure signal loss over time. | Use chemically modified biorecognition elements, such as phosphorothioate aptamers (PS-Apt), where a sulfur atom replaces a non-bridging oxygen in the phosphate backbone, to resist nuclease cleavage [42]. |

| Fouling of the nanomaterial surface | Inspect the electrode surface post-use with SEM or AFM for accumulated debris. | Integrate inherently antifouling nanomaterials like functionalized graphene oxide, whose hydrophilicity provides anti-adhesive features [40]. |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing Aptamer Stability with Phosphorothioate Modification

- Probe Design: Synthesize an aptamer sequence specific to your target (e.g., the SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein). For the experimental group, specify phosphorothioate (PS) modification at specific intermucleotide linkages during synthesis. [42]

- Sensor Fabrication: Immobilize both the traditional phosphate aptamer (PO-Apt) and the PS-Apt on separate, identically prepared electrodes (e.g., on a PANI-modified glassy carbon electrode). [42]

- Stability Test: Incubate both sensors in a solution containing a relevant nuclease (e.g., DNase I) or in human serum at 37°C.

- Performance Monitoring: At regular intervals, remove the sensors, wash them, and measure their response to a fixed concentration of the target protein using DPV.

- Analysis: Compare the signal retention of the PS-Apt sensor versus the PO-Apt sensor over time. The PS-Apt sensor is expected to maintain significantly higher sensitivity, demonstrating superior stability. [42]

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials used in developing fouling-resistant, nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Dendritic Zwitterionic Oligopeptides (e.g., EK(E)CE(K)K) [8] | Forms an ultra-stable hydration layer to prevent nonspecific adsorption in complex fluids. | 3D branched architecture; neutral net charge; forms strong intramolecular H-bonds; superior to linear peptides. |

| Arched-Peptide (APEP) (e.g., CPPPPSESKSESKSESKPPPPC) [42] | Provides a stable, hydrolysis-resistant antifouling layer on electrode surfaces. | Immobilized at both ends to form a stable arch; incorporates hydrophilic serine residues; resists enzymatic degradation. |