ROS Signaling Mechanisms: From Molecular Foundations to Therapeutic Targeting in Disease

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are central, dual-function regulators in cellular physiology, acting as crucial signaling molecules at low levels and as agents of oxidative damage at high concentrations.

ROS Signaling Mechanisms: From Molecular Foundations to Therapeutic Targeting in Disease

Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are central, dual-function regulators in cellular physiology, acting as crucial signaling molecules at low levels and as agents of oxidative damage at high concentrations. This article provides a comprehensive analysis of ROS signaling mechanisms for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore the fundamental biology of specific ROS molecules and their homeostatic regulation, detail advanced methodological approaches for studying redox biology, address key challenges in targeting ROS for therapy, and critically evaluate emerging therapeutic strategies. By integrating foundational concepts with cutting-edge applications, this review aims to bridge molecular understanding with clinical translation in cancer, neurodegenerative, and metabolic diseases.

The Dual Nature of ROS: Molecular Identity, Homeostatic Control, and Physiological Signaling

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a collection of oxygen-containing, highly reactive molecules generated as byproducts of aerobic metabolism within cells [1] [2] [3]. In a biological context, ROS are pervasive due to their formation from abundant molecular oxygen (Oâ‚‚) and water [2]. These molecules are intrinsically involved in cellular functioning, existing at low, stationary levels in normal cells where they play crucial roles in signaling and homeostasis [4] [2]. The ROS spectrum encompasses both free radicals, which contain unpaired electrons, and non-radical oxidizing agents [1] [3]. The delicate balance between ROS production and elimination is critical for cellular health; disruption of this equilibrium can lead to oxidative stress, with significant implications for cell fate, disease progression, and therapeutic responses [1] [5].

The traditional view of ROS as merely toxic agents has evolved significantly. Contemporary research reveals that ROS function as important signaling molecules that regulate diverse biological processes, including inflammation, proliferation, and cell death [4] [3]. This dual nature of ROS—acting as both critical signaling molecules and potential toxic agents—forms the foundation of modern redox biology [4]. The specific roles and effects of ROS depend on factors such as concentration, cellular environment, duration of exposure, and subcellular localization [4] [3]. Understanding the distinct properties and behaviors of individual ROS species is thus essential for researchers and drug development professionals working in this field.

The Core ROS Spectrum: Chemical Properties and Relationships

Fundamental ROS Chemistry and Interconversion

The generation of reactive oxygen species occurs primarily through the sequential reduction of molecular oxygen in a series of one-electron transfer steps [3]. This process begins with the monovalent reduction of oxygen to form superoxide anion (•Oâ‚‚â»), which subsequently undergoes further reduction and protonation to yield hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), the hydroxyl radical (•OH), and finally water [3]. These three species—•Oâ‚‚â», Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, and •OH—represent the primary ROS in biological systems, with many other oxidants derived from these fundamental sources [3].

The interconversion between different ROS occurs through well-defined chemical reactions that are tightly regulated in biological systems. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) catalyzes the disproportionation (dismutation) of •Oâ‚‚â» to form Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ [1] [2]. The highly reactive hydroxyl radical is generated primarily through the Fenton reaction, where Hâ‚‚O2 reacts with ferrous (Fe²âº) or cuprous ions, and through the Haber-Weiss reaction, which involves •Oâ‚‚â» and Hâ‚‚O2 [1] [4] [3]. Additionally, •Oâ‚‚â» can react with nitric oxide (•NO) to form peroxynitrite (ONOOâ»), a reactive nitrogen species that contributes significantly to oxidative damage [1] [3].

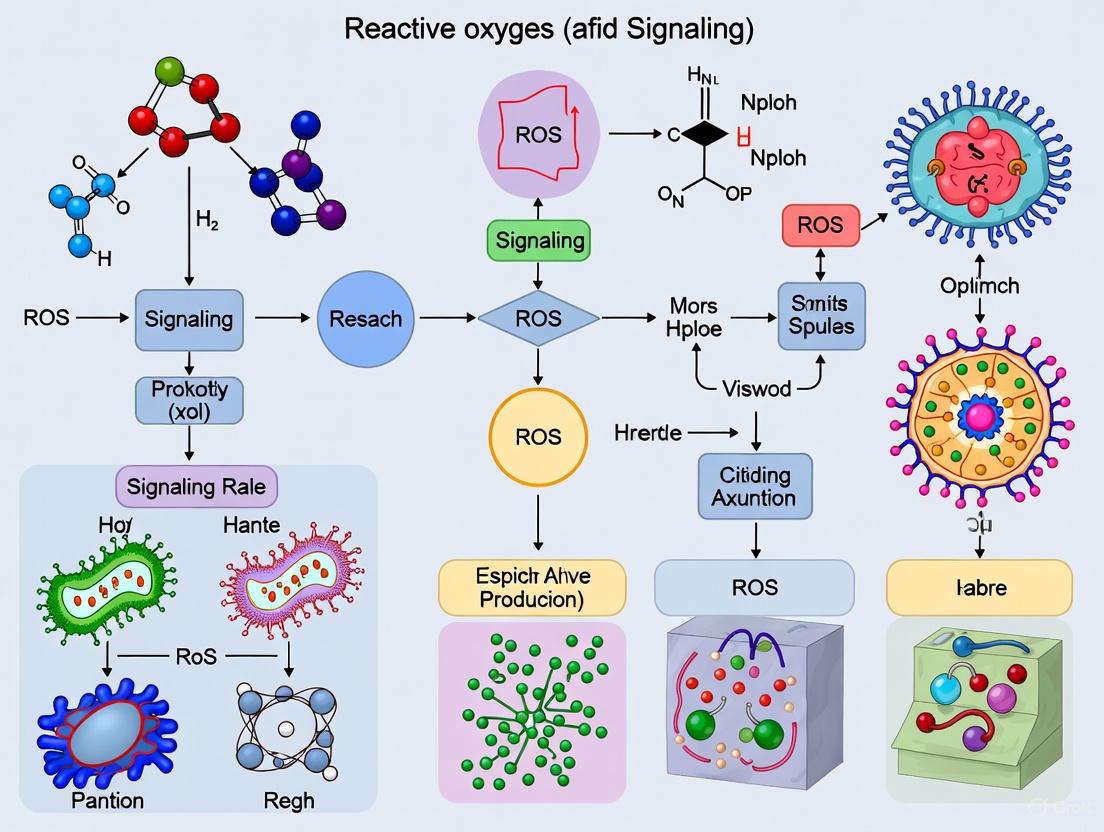

Figure 1: ROS Interconversion Pathways and Key Enzymatic Controls. This diagram illustrates the primary chemical pathways for ROS generation and elimination, highlighting the central role of antioxidant enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx).

Comprehensive Inventory of ROS Molecules

The ROS spectrum includes diverse chemical species with varying reactivity, lifespan, and biological targets. Table 1 provides a systematic overview of the core ROS molecules, their chemical properties, and primary characteristics relevant to biological systems.

Table 1: Comprehensive Inventory of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

| ROS Species | Chemical Formula | Type | Reactivity | Half-Life | Major Sources | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide anion | •O₂⻠| Free radical | Moderate | 1-5 μs | Mitochondrial ETC (Complex I, III), NOX enzymes | Primary ROS; membrane-impermeable; precursor to other ROS; inactivates Fe-S cluster proteins [1] [4] [5] |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Non-radical | Low-moderate | ~1 ms | SOD activity, NOX enzymes, peroxisomes | Membrane-permeable; key signaling molecule; oxidizes cysteine residues in proteins [1] [4] [5] |

| Hydroxyl radical | •OH | Free radical | Extremely high | ~1 ns | Fenton reaction, Haber-Weiss reaction | Most potent oxidant; non-selective; reacts instantaneously with all biomolecules [1] [4] [3] |

| Hydroperoxyl radical | HO₂• | Free radical | High | - | Protonation of •O₂⻠| Protonated form of superoxide; more lipid-soluble; contributes to lipid peroxidation [1] |

| Peroxyl radicals | RO₂• | Free radical | High | ms-range | Lipid peroxidation chain reactions | Propagate lipid peroxidation; relatively stable and diffusible; oxidize proteins and DNA [1] |

| Alkoxyl radicals | RO• | Free radical | High | - | Decomposition of RO₂• | Formed during lipid metabolism; abstract hydrogen atoms from biomolecules [1] |

| Carbonate radical anion | CO₃•⻠| Free radical | High | - | Reaction of CO₂ with peroxynitrite | Efficiently oxidizes guanine in DNA; generated in physiological environments [1] |

| Singlet oxygen | ¹O₂ | Non-radical | High | ~1 μs | Photosensitization, chlorophyll | Electronically excited state of oxygen; highly reactive with unsaturated compounds [6] [2] |

| Ozone | O₃ | Non-radical | High | - | Atmospheric pollutant | Strong oxidizing agent; included in broader ROS definitions [1] |

| Hypochlorous acid | HOCl | Non-radical | High | - | Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity | Powerful antimicrobial; oxidizes proteins, DNA, and lipids [1] [3] |

The reactivity of different ROS varies dramatically, spanning approximately nine orders of magnitude from the highly selective and relatively stable H₂O₂ to the extremely reactive and non-selective •OH [5]. This diversity in chemical behavior directly influences their biological roles, with less reactive species like H₂O₂ functioning effectively as signaling molecules due to their ability to diffuse and react selectively with specific cellular targets, while highly reactive species like •OH primarily cause oxidative damage [4] [5].

Endogenous ROS Generation Sites

Cellular ROS originate from multiple subcellular compartments, with the mitochondrial electron transport chain and NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes representing the most significant sources [1] [3]. Mitochondria generate ROS primarily at Complex I (NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase) and Complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase) of the respiratory chain, where electron leakage to oxygen results in •O₂⻠formation [2] [3]. Under normal physiological conditions, approximately 0.1-2% of electrons passing through the transport chain contribute to ROS generation, though this percentage can increase dramatically during mitochondrial dysfunction or under stress conditions [2].

NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes represent another major source of cellular ROS, with these transmembrane enzymes specifically dedicated to ROS production [1] [4]. NOX enzymes utilize NADPH to reduce oxygen, directly producing H₂O₂ (as in the case of NOX4, DUOX1/2) or indirectly via •O₂⻠generation (NOX1-3) [1]. Unlike mitochondrial ROS production, which occurs as a byproduct of energy metabolism, NOX-derived ROS function primarily in signaling and defense mechanisms [4].

Additional intracellular ROS sources include the endoplasmic reticulum, where protein folding generates oxidative conditions; peroxisomes, which contain various oxidases; and cytochrome P450 systems involved in detoxification and steroid synthesis [1] [3]. Uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), xanthine oxidase activity, and cyclooxygenases also contribute to the cellular ROS pool [3].

Experimental Systems for Controlled ROS Generation

For rigorous investigation of ROS effects and signaling pathways, researchers employ specific experimental systems to generate particular ROS species in a controlled manner. Table 2 outlines established methodologies for selective ROS generation in biological research contexts.

Table 2: Experimental Approaches for Selective ROS Generation in Research

| Target ROS | Experimental Approach | Mechanism | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide (•Oâ‚‚â») | Paraquat (PQ) or quinones | Redox cycling compounds that generate •Oâ‚‚â» | Increases both •Oâ‚‚â» and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ (via dismutation); specific concentrations required for controlled generation [5] |

| Superoxide (•Oâ‚‚â») in mitochondria | MitoPQ | Mitochondria-targeted analog of paraquat | Generates •Oâ‚‚â» within mitochondria; allows compartment-specific investigation [5] |

| Hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Glucose oxidase | Enzyme that generates Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ while oxidizing glucose | Direct Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production; flux can be regulated by glucose concentration [5] |

| Hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) in specific cellular compartments | d-amino acid oxidase (DAAO) expression | Genetically expressed enzyme generates Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ when provided with d-amino acids | Compartment-targeted expression possible; flux regulated by d-alanine concentration; enables spatiotemporal control [5] |

| Superoxide/Hydrogen peroxide | NADPH oxidase (NOX) activation/modulation | Physiological activation or genetic manipulation of NOX enzymes | Specific inhibitors or genetic deletion/knockdown of NOX components recommended for validation [5] |

These controlled generation systems enable researchers to establish causal relationships between specific ROS and biological outcomes, moving beyond correlative observations. The use of compartment-specific ROS generation is particularly valuable for investigating spatially restricted signaling events [5].

ROS Signaling Mechanisms and Molecular Targets

Redox-Sensitive Protein Modifications

ROS function as signaling molecules primarily through the reversible oxidation of specific amino acid residues in proteins, particularly cysteine and methionine [4] [7]. These oxidative post-translational modifications (Oxi-PTMs) serve as molecular switches that regulate protein function, localization, and interactions [7]. Cysteine residues exist as thiolate anions (Cys-Sâ») at physiological pH, making them particularly susceptible to oxidation by Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to form sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH) [4]. This primary oxidation product can undergo further reversible modifications, including the formation of disulfide bonds (S-S), S-glutathionylation (SSG), and S-nitrosylation (SNO) [8] [7].

These oxidative modifications induce allosteric changes in protein structure that alter function, with the modifications being reversed by cellular reductase systems such as thioredoxin (Trx) and glutaredoxin (Grx) [4]. This reversible oxidation represents a fundamental mechanism of redox signaling that regulates diverse cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and stress responses [4] [8]. At higher concentrations, further oxidation to sulfinic (Cys-SO₂H) and sulfonic (Cys-SO₃H) acids can occur, which may be irreversible and result in permanent protein damage, representing the transition from redox signaling to oxidative stress [4].

Specific Signaling Pathways Regulated by ROS

ROS, particularly Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, regulate several key signaling pathways central to cellular physiology and pathology. Growth factor signaling represents a well-characterized example, where receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) activation by epidermal growth factor (EGF) or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) stimulates ROS production through NADPH oxidases [4]. The resulting Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ transiently oxidizes and inactivates protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) such as PTP1B and PTEN by modifying their catalytic cysteine residues, thereby prolonging tyrosine phosphorylation and enhancing mitogenic signaling [4]. This precise spatial and temporal regulation is achieved through localized inactivation of peroxiredoxin I (PRXI) at cell membranes upon growth factor stimulation, allowing controlled Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ accumulation in specific microdomains [4].

In cancer biology, oncogenic transformation often involves hijacking these normal ROS signaling mechanisms. Cancer cells driven by oncogenes such as MYC and KRAS demonstrate dependence on both mitochondrial and NOX-derived ROS for proliferation, with antioxidant treatments or ROS inhibition suppressing tumorigenic signaling pathways [4]. The transcription factor NF-κB represents another important redox-sensitive signaling node, with ROS activating this pathway to promote cell survival in many tumor contexts [4].

Figure 2: ROS-Mediated Growth Factor Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates how hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) functions as a secondary messenger in growth factor signaling by reversibly inactivating protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) and PTEN, thereby enhancing proliferative signaling pathways. The system is reset by reductase enzymes like thioredoxin.

Methodologies for ROS Measurement and Detection

Guidelines for Specific ROS Detection

Accurate measurement of specific ROS presents significant technical challenges due to their reactive nature, short half-lives, and low physiological concentrations. The field has established that different ROS require distinct detection approaches, and reliance on non-specific commercial "ROS detection kits" can yield misleading results [5]. Proper experimental design requires consideration of the specific chemical properties, reactivity, and biological context of the ROS being studied [5].

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, also known as electron spin resonance (ESR), represents one of the most specific methods for direct detection of radical species, particularly when used with spin traps that form stable adducts with short-lived radicals [5]. However, this technique requires specialized instrumentation and expertise. Fluorescent and luminescent probes offer more accessible alternatives but vary significantly in their specificity [5]. For example, dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and related probes are widely used but lack specificity for particular ROS and are subject to numerous artefacts, while more specific probes like Amplex Red for H₂O₂ or hydroxyphenyl fluorescein (HPF) for •OH provide better selectivity [5].

A critical principle in ROS measurement is that most probes capture only a small percentage of the ROS generated, and this percentage must remain relatively constant across different experimental conditions to allow valid comparisons [5]. Furthermore, researchers should recognize that complete scavenging of highly reactive species like •OH is chemically implausible in biological systems due to their nearly instantaneous reaction with biomolecules, making interpretations based solely on "•OH scavengers" problematic [5].

Assessment of Oxidative Damage Biomarkers

When direct ROS measurement proves challenging, researchers often quantify stable products of oxidative damage as biomarkers for ROS activity. The most common biomarkers include products of lipid peroxidation such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), which can be measured by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assays or more specific chromatographic methods [1] [3]. Protein carbonylation represents another well-established marker of oxidative protein damage, typically detected through derivatization with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) followed by immunoblotting or spectrophotometric analysis [5].

For DNA damage assessment, measurement of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) provides a specific marker of oxidative DNA lesions, typically quantified using HPLC with electrochemical detection or immunoassays [5]. Importantly, the measured level of any oxidative damage biomarker represents the net balance between its rate of production and its removal by cellular repair, degradation, and excretion mechanisms [5]. Therefore, changes in biomarker levels could reflect alterations in either production or clearance pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for ROS Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Generators | Paraquat, MitoPQ | Selective •Oâ‚‚â» generation | Paraquat for general •Oâ‚‚â»; MitoPQ for mitochondrial-specific generation [5] |

| d-amino acid oxidase (DAAO) expression systems | Controlled Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ generation in specific compartments | Allows spatiotemporal control with d-alanine substrate [5] | |

| ROS Scavengers/Modulators | N-acetylcysteine (NAC) | Increases cellular cysteine and glutathione levels | Often misinterpreted as direct ROS scavenger; has multiple mechanisms including Hâ‚‚S generation [4] [5] |

| TEMPO/TEMPOL, mito-TEMPO | Redox modulators | Complex redox reactions; better described as redox modulators than specific antioxidants [5] | |

| Superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetics | Catalyze •O₂⻠dismutation to H₂O₂ | Porphyrin-based compounds; validate specificity [5] | |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | NOX inhibitors (specific) | Inhibit NADPH oxidase activity | Use genetically validated inhibitors; avoid non-specific agents like apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium as sole evidence [5] |

| Detection Reagents | Amplex Red | Specific Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ detection | Fluorimetric detection of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ via horseradish peroxidase-coupled reaction [5] |

| Hydroethidine (Dihydroethidium) | •O₂⻠detection | Specificity depends on separation and detection of 2-hydroxyethidium product [5] | |

| Spin traps (DMPO, DEPMPO) | EPR detection of radical species | Form stable adducts with short-lived radicals for EPR detection [5] | |

| Daraxonrasib | Daraxonrasib, CAS:2765081-21-6, MF:C44H58N8O5S, MW:811.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MB-0223 | MB-0223, MF:C26H27N5OS, MW:457.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This toolkit provides researchers with essential reagents for manipulating and measuring ROS in experimental systems, though appropriate controls and validation are always necessary when interpreting results.

The ROS spectrum encompasses a diverse array of chemical species with distinct properties and biological activities. From the relatively stable signaling molecule H₂O₂ to the highly destructive hydroxyl radical, each ROS species plays specific roles in cellular physiology and pathology. Understanding these differences is fundamental to advancing redox biology research and developing targeted therapeutic approaches. The experimental frameworks and methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with essential tools for rigorous investigation of ROS in biological systems, with appropriate attention to the chemical specificity and technical considerations required for meaningful results. As the field continues to evolve, recognition of the dual nature of ROS—as both essential signaling molecules and potential agents of damage—will remain central to unraveling their complex roles in health and disease.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) function as crucial signaling molecules in physiological processes, yet their overproduction leads to oxidative stress and cellular damage. Understanding the precise sources and generation mechanisms of ROS is fundamental to elucidating their dual role in health and disease. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of three major cellular ROS sources: the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes, and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Within the broader context of ROS signaling mechanisms research, we detail the molecular architecture of each system, quantitative ROS production data, and advanced experimental methodologies for their study, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals targeting redox-based therapeutics.

Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain

Structural Organization and ROS Generation Sites

The mitochondrial ETC is a primary source of endogenous ROS, comprising complexes I-IV alongside mobile electron carriers ubiquinone and cytochrome c. The complexes assemble into supercomplexes with specific configurations to function properly [9]. Electron flow through the ETC is coupled to proton pumping across the inner mitochondrial membrane, generating the proton motive force used by ATP synthase (Complex V) for ATP production [9].

During electron transfer, a small percentage of electrons directly leak to oxygen, generating superoxide anions (O₂•â») at specific sites within the ETC. Table 1 summarizes the characterized ROS generation sites within the ETC supercomplex.

Table 1: Mitochondrial ETC ROS Generation Sites

| Complex | ROS Generation Site | Substrate/Pathway | Primary ROS Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I | Site IF (Flavin mononucleotide) | NADH oxidation | O₂•⻠[9] |

| Complex I | Site IQ (Ubiquinone binding site) | Reverse electron transport from CoQ pool | O₂•⻠[9] [10] |

| Complex II | Site IIF (Flavin adenine dinucleotide) | Succinate oxidation | O₂•⻠[9] [10] |

| Complex III | Site IIIQo (Ubiquinol oxidation site) | Q-cycle during ubiquinol oxidation | O₂•⻠[9] |

The electron transfer process begins at Complex I (CI, NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase), which accepts electrons from NADH. The L-shaped eukaryotic CI contains a matrix arm with an FMN cofactor and multiple iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, and a membrane arm with seven hydrophobic subunits [9]. Electrons from NADH reduce FMN to FMNHâ‚‚, then pass through a chain of Fe-S clusters before reducing ubiquinone to ubiquinol. The major ROS generation site in CI is the FMN cofactor (Site IF), particularly when the electron transport is slow and the flavin semiquinone state reacts with Oâ‚‚. Additionally, the ubiquinone binding site (Site IQ) can generate significant ROS, especially during reverse electron transport from a highly reduced ubiquinone pool [9].

Complex II (CII, succinate dehydrogenase) directly links the TCA cycle to the ETC, catalyzing succinate oxidation to fumarate. Its four subunits include a flavoprotein with FAD and three Fe-S clusters. Electrons from succinate reduce FAD to FADHâ‚‚, then pass through the Fe-S clusters to reduce ubiquinone. ROS (O₂•â») is generated primarily at the FAD site (Site IIF) [9].

In Complex III (CIII, cytochrome bc₠complex), the Q-cycle mechanism for ubiquinol oxidation creates a stabilized ubisemiquinone radical intermediate at the Qo site (Site IIIQo), which can directly reduce O₂ to O₂•⻠[9]. This site represents a significant source of mitochondrial ROS.

Regulatory Mechanisms and Physiological Significance

Mitochondrial ROS production is tightly regulated. A key mechanism is proton leak, which dissipates the proton gradient and reduces the driving force for ROS generation. This leak comprises basal proton leak and induced proton leak regulated by uncoupling proteins (UCP1-5) [9] [10]. UCP1 mediates non-shivering thermogenesis, while UCP2-5 primarily function to reduce oxidative stress and exert cytoprotective effects [9]. All diseases involving oxidative stress are associated with UCPs, highlighting their therapeutic relevance [10].

The following diagram illustrates the primary ROS generation sites within the mitochondrial ETC and their connectivity.

NADPH Oxidase (NOX) Enzyme Family

NOX Isoforms and Molecular Mechanisms

The NADPH oxidase (NOX) family comprises seven transmembrane enzymes (NOX1-5, DUOX1-2) dedicated to regulated, non-mitochondrial ROS generation. Unlike mitochondrial ROS production, which is a byproduct of metabolism, NOX enzymes are professional ROS producers, primarily generating superoxide anion (O₂•â») or hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [11] [12]. Their core function is electron transfer from cytosolic NADPH across the membrane to molecular oxygen.

Table 2 outlines the key characteristics of human NOX isoforms, highlighting their tissue distribution, required regulatory components, and primary ROS products.

Table 2: Human NADPH Oxidase (NOX) Family Isoforms

| Isoform | Tissue Distribution | Regulatory Components | Primary ROS Product | Physiological & Pathological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOX1 | Colon, Vascularure | NOXO1, NOXA1, Rac | O₂•⻠| Host defense, vascular pathology [11] |

| NOX2 | Phagocytes, Endothelium | p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, Rac | O₂•⻠| Microbial killing, inflammation [11] |

| NOX3 | Inner Ear | p47phox, NOXO1 | O₂•⻠| Vestibular development [11] |

| NOX4 | Kidney, Vascularure | p22phox | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Oxygen sensing, fibrosis, cancer [11] [13] |

| NOX5 | Spleen, Testis | Ca²⺠| O₂•⻠| Cell proliferation, angiogenesis [11] |

| DUOX1/2 | Thyroid, Lung | DUOXA1/2, Ca²⺠| H₂O₂ | Thyroid hormone synthesis, innate immunity [11] |

The catalytic core of a NOX enzyme typically consists of a transmembrane heterodimer (NOX/p22phox). The activation mechanisms vary by isoform. For example, NOX2, the prototype first identified in phagocytes, requires the assembly of cytosolic regulatory subunits (p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, and Rac GTPase) at the membrane for activation upon infection [11]. In contrast, NOX4 is constitutively active, primarily produces Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ due to its extracellular dehydrogenase domain, and requires only p22phox for stability and activity [11] [13]. NOX4 is also uniquely associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and other organelles [13].

NOX Enzymes as Therapeutic Targets in Disease

Dysregulation of NOX-derived ROS is implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, hypertension, diabetic nephropathy, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases [11] [12]. Consequently, NOX enzymes represent promising therapeutic targets. The development of isoenzyme-selective inhibitors is a critical focus, as broad-spectrum antioxidants have shown limited clinical efficacy and potential off-target effects [12]. Recent efforts have utilized in silico screening and high-throughput assays to identify selective inhibitors that target the active site of NOX enzymes, showing promise in pre-clinical cancer models, particularly in combination with KRAS modulators [12].

The diagram below depicts the general activation mechanism of a prototypical NOX complex, NOX2.

Endoplasmic Reticulum

Protein Folding, ER Stress, and ROS Generation

The endoplasmic reticulum is a central hub for protein synthesis, folding, and post-translational modification. The oxidative environment of the ER lumen is optimized for disulfide bond formation, a critical step in the maturation of secretory and membrane proteins. This process is a major source of ROS within the ER [13] [14].

The enzyme protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) catalyzes disulfide bond formation and isomerization in substrate proteins. During this reaction, PDI becomes reduced. To regenerate active, oxidized PDI, electrons are transferred via endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1) to molecular oxygen (Oâ‚‚), which acts as the final electron acceptor, thereby generating Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ as a byproduct [13]. It is estimated that approximately 25% of total cellular ROS are generated by disulfide bond formation in the ER during oxidative protein folding [13].

An imbalance between the protein-folding load and the ER's capacity leads to ER stress, triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is orchestrated by three main ER transmembrane sensors: IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6. Under severe or prolonged ER stress that cannot be resolved, the UPR switches from pro-survival to pro-apoptotic signaling [13] [14].

NOX4 and Calcium-Mediated ROS in the ER

Beyond protein folding, the ER hosts other ROS-generating systems. NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) is localized to the ER, among other organelles [13]. NOX4 constitutively produces Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and its expression is upregulated during ER stress, contributing to the overall ROS load and influencing both pro-adaptive and pro-apoptotic UPR signaling [13]. For instance, NOX4-derived ROS can promote autophagy as a protective mechanism, but can also lead to apoptosis if the stress is severe [13].

Furthermore, ER stress can disrupt calcium (Ca²âº) homeostasis, leading to the release of Ca²⺠into the cytosol. This Ca²⺠can be taken up by mitochondria, stimulating mitochondrial ROS production and creating a damaging cycle of oxidative stress between the two organelles [14].

The interconnected pathways of ER stress and ROS generation are summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies

Quantitative ROS Measurement: Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR)

Direct measurement of highly reactive and short-lived ROS is methodologically challenging. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, coupled with spin traps, is considered the gold standard for direct, quantitative detection of radical species like O₂•⻠in biological samples [15]. This technique provides an "instantaneous" snapshot of ROS production, unlike indirect methods that measure accumulated oxidative damage.

A validated microinvasive protocol involves collecting 50 μL of human capillary blood in heparinized tubes. The blood sample is immediately mixed with a spin trap molecule (e.g., CMH: 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine) [15]. The spin trap reacts with short-lived radicals to form stable, EPR-detectable adducts. The EPR spectrum is recorded, and the signal amplitude is proportional to the absolute concentration of ROS in the blood sample. This method has demonstrated a significant linear relationship (R² = 0.95) between ROS measured in capillary and venous blood, validating its reliability for clinical and research applications [15].

Experimental Protocol for Assessing NOX Inhibition

The development of specific NOX inhibitors is a key therapeutic endeavor. The following protocol outlines a combined in silico and experimental approach for identifying and validating NOX inhibitors, as described in recent research [12].

- In Silico Screening: Perform a virtual high-throughput screen of compound libraries against the crystal structure of the dehydrogenase (DH) domain of a NOX isoform (e.g., csNOX5). Docking simulations predict compounds that potentially occupy the NADPH-binding active site.

- In Vitro Enzymatic Assay: Validate hits using a cell-free system. Recombinantly express and purify the NOX DH domain. Measure the inhibitor's effect on the enzyme's ability to catalyze the reduction of an electron acceptor (e.g., cytochrome c or ferricyanide) in the presence of NADPH. A decrease in the reduction rate indicates inhibition.

- Binding Validation (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay - CETSA): Confirm direct binding in a cellular context. Treat cells expressing the target NOX with the inhibitor or vehicle control. Heat the cell lysates across a range of temperatures. The binding of a ligand stabilizes the protein, shifting its denaturation curve. This stabilization can be detected by immunoblotting, confirming target engagement within the complex cellular environment [12].

- In Cellulo ROS Measurement: Assess the functional consequence of inhibition in living cells. Use a cell-permeable, ROS-sensitive fluorescent probe (e.g., DCFH-DA or Amplex Red) in a high-throughput plate reader format. Treat various cancer cell lines with the inhibitor and measure the reduction in fluorescence, which corresponds to a decrease in cellular ROS production. This step also assesses selectivity and synergy with other drugs (e.g., KRAS modulators) [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ROS Source Research

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Target | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Spin Traps (e.g., CMH) | EPR: Forms stable adducts with O₂•⻠for direct detection | Used in microinvasive blood ROS measurement [15] |

| ROS-Sensitive Fluorescent Probes | General & In Cellulo: Becomes fluorescent upon oxidation | DCFH-DA (general ROS), Amplex Red (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [12] |

| Isozyme-Selective NOX Inhibitors | Pharmacology: Inhibits specific NOX isoforms; therapeutic potential | Identified via in silico screening of NOX5 active site [12] |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Target Engagement: Confirms drug binding to target protein in cells | Validates direct interaction between inhibitor and NOX [12] |

| Antibody for Nox4 | Localization/Expression: Detects endogenous NOX4 protein | First monoclonal antibody for Nox4 localized it to plasma membrane & ER [13] |

| ETF (Electron Transfer Flavoenzyme) | Model System: Study of flavoprotein magnetic field sensing & ROS | Recombinant human ETF used to study ROS partitioning (O₂•⻠vs H₂O₂) [16] |

| FPFT-2216 | FPFT-2216, MF:C12H12N4O3S, MW:292.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 10-Deacetyl-7-xylosyl Paclitaxel | 10-Deacetyl-7-xylosyl Paclitaxel, MF:C50H57NO17, MW:944.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes, and endoplasmic reticulum represent three structurally and functionally distinct cellular systems that collectively govern the delicate balance of ROS signaling and oxidative stress. The ETC generates ROS as a byproduct of aerobic metabolism, NOX enzymes produce ROS in a highly regulated manner for signaling and host defense, and the ER contributes to the ROS pool primarily through its oxidative protein folding machinery. Advanced techniques like EPR and the development of isozyme-specific inhibitors are refining our ability to dissect the contributions of these sources. A deep, mechanistic understanding of these systems is paramount for developing targeted therapeutic strategies aimed at manipulating redox pathways in a wide spectrum of human diseases, from cancer and neurodegeneration to metabolic and inflammatory disorders.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) function as critical signaling molecules at physiological levels but induce oxidative damage and pathology at elevated concentrations. Antioxidant defense systems maintain this delicate balance through an integrated network of enzymatic and non-enzymatic components. This whitepaper provides a technical overview of these systems, focusing on the core enzymatic antioxidants—superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx)—and their coordination with non-enzymatic networks. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide includes summarized quantitative data, detailed experimental methodologies, and visualizations of key signaling pathways to support advanced research in redox biology and therapeutic development.

Reactive oxygen species are inevitable byproducts of aerobic metabolism, originating primarily from the mitochondrial electron transport chain and enzymatic systems like NADPH oxidases (NOX) [3] [4]. ROS include a range of molecules, such as the superoxide anion (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and the highly reactive hydroxyl radical (•OH) [3] [17]. The biological role of ROS is fundamentally dualistic. At low, physiological levels, particularly Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, they act as crucial second messengers in redox signaling, regulating processes like proliferation, inflammation, and immune response through the reversible oxidation of cysteine residues in target proteins such as protein tyrosine phosphatases [4] [8]. However, when ROS generation overwhelms cellular detoxification capacity—a state known as oxidative stress—they cause indiscriminate damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA, contributing to aging, neurodegeneration, and cancer [3] [4] [8].

The antioxidant defense system exists to manage this delicate equilibrium, ensuring redox homeostasis. This network is not a simple scavenger but a sophisticated, multi-layered system. The first line of defense is composed of powerful enzymes like SOD, CAT, and GPx, which work in concert to directly neutralize specific ROS [18] [8] [19]. This enzymatic effort is supported by a second line of non-enzymatic antioxidants, including the glutathione (GSH) and thioredoxin systems, which help recycle oxidized cellular components and provide reducing power [8] [20]. Understanding the structure, function, and regulation of these components, particularly the core enzymatic antioxidants, is essential for developing therapeutic strategies against a myriad of oxidative stress-related diseases.

Core Enzymatic Antioxidants

The first line of defense comprises metalloenzymes that catalytically neutralize primary ROS. Their activity is compartmentalized, inducible, and essential for mitigating the chain-propagation of oxidative damage.

Superoxide Dismutase

SODs are a family of enzymes that catalyze the dismutation (or partitioning) of two superoxide anions into hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen. This reaction occurs at an extremely fast rate, close to the diffusion limit, and is the primary defense against O₂•⻠[19].

Table 1: Types and Properties of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

| Type / Acronym | Metal Cofactors | Subcellular Localization | Key Structural Features | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOD1 (Cu/Zn-SOD) | Cu²⺠(catalytic), Zn²⺠(structural) | Cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondrial intermembrane space [19] | 32 kDa homodimer; electrostatic loop guides O₂•⻠to active site [19] | First defense against cytosolic O₂•â»; major intracellular SOD [18] [19] |

| SOD2 (Mn-SOD) | Mn³⺠(catalytic) | Mitochondrial matrix [19] | 96 kDa homotetramer; synthesized with a mitochondrial targeting signal [19] | Scavenges O₂•⻠generated by the electron transport chain [3] [19] |

| SOD3 (EC-SOD) | Cu²⺠(catalytic), Zn²⺠(structural) | Extracellular matrix, cell surfaces, extracellular fluids [19] | 135 kDa homotetramer; binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans [19] | Maintains redox balance in extracellular space; regulates signaling [19] |

SOD activity is critical for preventing the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOOâ»), a highly damaging reactive nitrogen species generated from the reaction between O₂•⻠and nitric oxide (•NO) [3]. The Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ produced by SOD is further processed by other enzymes like CAT and GPx, placing SOD at the apex of the enzymatic antioxidant cascade.

Catalase

Catalase is a highly efficient enzyme located predominantly in peroxisomes, where it catalyzes the conversion of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen. It is a tetrameric heme-containing enzyme that operates most effectively at high H₂O₂ concentrations, making it a crucial buffer against significant peroxide loads [18] [8]. Its primary reaction is the disproportionation of H₂O₂: 2 H₂O₂ → 2 H₂O + O₂ [3]. While its role is often seen as purely detoxifying, the H₂O₂ it decomposes is also a signaling molecule, implying that catalase indirectly influences redox-sensitive signaling pathways [4].

Glutathione Peroxidase

Glutathione Peroxidase represents a family of enzymes that reduce Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and organic hydroperoxides (LOOH) to water and corresponding alcohols, respectively. This activity is essential for protecting membranes from lipid peroxidation [18] [8]. Unlike catalase, GPx utilizes reduced glutathione (GSH) as its reducing agent, coupling Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ detoxification to the glutathione redox cycle.

The core reaction is: H₂O₂ + 2 GSH → 2 H₂O + GSSG (oxidized glutathione) [8]. The resulting GSSG is then reduced back to GSH by the enzyme glutathione reductase (GR), which consumes NADPH. This creates a metabolic link between antioxidant defense and cellular energy status [8]. GPx enzymes often contain selenium at their active site, which is critical for their catalytic activity [8].

Table 2: Key Enzymatic Antioxidants and Their Properties

| Enzyme | Catalytic Reaction | Cofactor / Cysteine | Cellular Localization | Key Role in Defense |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | 2 O₂•⻠+ 2H⺠→ H₂O₂ + O₂ | Cu/Zn, Mn, Fe | Cytosol (SOD1), Mitochondria (SOD2), Extracellular (SOD3) [19] | Primary defense against superoxide anion [18] [19] |

| Catalase (CAT) | 2 H₂O₂ → 2 H₂O + O₂ | Heme | Peroxisomes [8] | High-capacity removal of H₂O₂ [18] [8] |

| Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx) | H₂O₂ + 2 GSH → GSSG + 2 H₂O (or ROOH + 2 GSH → GSSG + ROH + H₂O) | Selenium (as selenocysteine) | Cytosol, Mitochondria [8] | Reduces H₂O₂ and lipid hydroperoxides using glutathione [18] [8] |

The following diagram illustrates the coordinated action of these primary enzymatic antioxidants and their integration with key regulatory systems.

Non-enzymatic Antioxidant Networks

The enzymatic defense is powerfully complemented by a suite of non-enzymatic molecules. These compounds act as direct ROS scavengers, cofactors for enzymes, and regulators of the redox proteome.

- Glutathione (GSH): This tripeptide (γ-glutamyl-cysteinyl-glycine) is the most abundant low-molecular-weight thiol in cells. It functions as a direct scavenger of ROS, a cofactor for GPx, and a redox buffer that maintains protein cysteine residues in their reduced state. The ratio of reduced glutathione (GSH) to its oxidized form (GSSG) is a key indicator of cellular redox status [8] [20].

- The Thioredoxin System: Comprising thioredoxin (Trx), thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), and NADPH, this system is crucial for reducing disulfide bonds in proteins, thus regulating protein function and signaling. It works in parallel with the glutathione system to control the cellular redox environment and is negatively regulated by TXNIP (Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein) [8] [20].

- Other Key Molecules:

- Ascorbate (Vitamin C): A potent water-soluble antioxidant that can directly scavenge various ROS and regenerate other antioxidants like vitamin E [21].

- Tocopherols (Vitamin E): Lipid-soluble antioxidants that are critical for terminating lipid peroxidation chain reactions in membranes [21].

- Polyphenols & Flavonoids: A diverse class of plant-derived compounds that can act as hydrogen donors, metal chelators, and in some cases, inducers of the Nrf2 pathway [17] [22].

Regulatory Signaling Pathways

The antioxidant defense system is not static; it is dynamically regulated by several signaling pathways that sense oxidative stress and mount a compensatory transcriptional response.

The Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Pathway

The transcription factor Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is the master regulator of cytoprotective gene expression. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its inhibitor, Keap1, and targeted for proteasomal degradation. Upon oxidative or electrophilic stress, specific cysteine residues in Keap1 are modified, leading to Nrf2 stabilization. Nrf2 then translocates to the nucleus, binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), and drives the expression of a vast network of genes, including those for SOD, CAT, GPx, glutathione synthesis enzymes (GCL, GSS), and proteins involved in xenobiotic metabolism and proteostasis [23] [8]. This pathway is a primary target for therapeutic interventions aimed at boosting endogenous antioxidant capacity.

Crosstalk with Inflammatory Pathways

A critical intersection exists between redox and inflammatory signaling. The transcription factor NF-κB is activated by various stimuli, including ROS, and promotes the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Conversely, Nrf2 activation can suppress NF-κB signaling, creating a counter-regulatory loop that limits excessive inflammation [23] [17]. Furthermore, in metabolic syndrome, GLP-1 receptor signaling has been shown to downregulate the expression of TXNIP, thereby enhancing thioredoxin activity and attenuating oxidative stress and inflammation [20].

The following diagram illustrates the core Nrf2 signaling mechanism.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Antioxidant Function

Robust methodologies are essential for evaluating the activity and function of antioxidant systems in research models. Below are detailed protocols for key assays.

Measuring SOD Activity

Principle: SOD activity is typically measured by its ability to inhibit the reduction of a tetrazolium salt (e.g., cytochrome c or nitrobue tetrazolium) by superoxide anion generated by a xanthine/xanthine oxidase system.

Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare a solution containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 0.1 mM EDTA, 50 µM xanthine, and 25 µM nitrobue tetrazolium (NBT).

- Enzyme Source: Add the sample containing SOD (cell lysate, tissue homogenate, or purified enzyme).

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding xanthine oxidase to a final concentration sufficient to produce a linear increase in absorbance at 560 nm in the absence of SOD.

- Kinetic Measurement: Monitor the increase in absorbance at 560 nm for 5-10 minutes. The reduction of NBT by superoxide produces a blue formazan.

- Calculation: One unit of SOD activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that causes 50% inhibition of the NBT reduction rate under specified conditions. Calculate activity relative to a standard curve of purified SOD [19].

Measuring Catalase Activity

Principle: Catalase activity is directly measured by the disappearance of its substrate, Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, which can be tracked spectrophotometrically by its absorbance at 240 nm.

Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare a solution of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10-20 mM Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚.

- Baseline: Record the initial absorbance at 240 nm.

- Initiate Reaction: Add the sample to the cuvette and mix rapidly.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately monitor the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm for 30-60 seconds. The molar extinction coefficient of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ at 240 nm is 43.6 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹.

- Calculation: Enzyme activity is calculated using the formula: Activity (U/mL) = (ΔA₂₄₀ / min × Total Volume) / (43.6 × Sample Volume), where U is defined as the amount of enzyme that decomposes 1 µmol of H₂O₂ per minute [18].

Measuring GPx Activity

Principle: GPx activity is assayed indirectly by coupling the reduction of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ (or tert-butyl hydroperoxide) to the oxidation of GSH, and then measuring the consumption of NADPH by glutathione reductase (GR), which recycles GSSG back to GSH.

Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM NADPH, 2 mM GSH, and 1 unit of Glutathione Reductase.

- Enzyme Source: Add the sample.

- Baseline: Record the initial absorbance at 340 nm.

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ or cumene hydroperoxide to a final concentration of 0.2-0.5 mM.

- Kinetic Measurement: Monitor the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm (due to NADPH oxidation) for 3-5 minutes.

- Calculation: Enzyme activity is calculated using the molar extinction coefficient of NADPH (6.22 mMâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹). One unit of GPx is defined as the amount that oxidizes 1 µmol of NADPH per minute [8].

Evaluating Intracellular ROS Levels

Principle: Cell-permeable, fluorescent dyes are oxidized by specific ROS, leading to an increase in fluorescence.

Protocol (using Hâ‚‚DCFDA):

- Cell Preparation: Seed cells in a black-walled, clear-bottom 96-well plate and treat as required.

- Loading Dye: Wash cells with PBS and load with 10-20 µM H₂DCFDA in serum-free media. Incubate for 30-60 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Stimulation and Measurement: Wash cells to remove excess dye. Add an oxidative stress inducer (e.g., Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). Immediately measure fluorescence (Ex/Em ~485/535 nm) kinetically over 60-120 minutes using a microplate reader [22].

- Analysis: Fluorescence intensity is normalized to cell number (e.g., via a parallel MTT assay) and expressed as a percentage of the control.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Antioxidant and Redox Research

| Reagent / Assay | Function & Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚DCFDA (Dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate) | Cell-permeable fluorescent probe for general oxidative stress; measures Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and peroxynitrite-related activity [22]. | Quantifying overall intracellular ROS levels in response to a drug treatment in cultured cells [22]. |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondria-targeted fluorescent probe for selective detection of mitochondrial superoxide [22]. | Assessing mitochondrial-specific ROS production in models of neurodegeneration or ischemia-reperfusion. |

| NADPH/NADP+ Assay Kits | Colorimetric or fluorometric measurement of the NADPH/NADP+ ratio, a key indicator of cellular redox state and reducing power [8]. | Evaluating the metabolic capacity for antioxidant defense (e.g., in GPx/GR and TrxR cycles). |

| GSH/GSSG Assay Kits | Quantifies the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione, a central biomarker of cellular redox status [8]. | Determining the effectiveness of an Nrf2 activator in maintaining a reduced cellular environment. |

| Nrf2 Activators (e.g., Sulforaphane, DMF) | Pharmacological or natural compounds that disrupt the Keap1-Nrf2 interaction, leading to Nrf2 stabilization and ARE-driven gene transcription [23]. | Experimental upregulation of the entire antioxidant network in disease models. |

| siRNA/shRNA for Nrf2, Keap1, SOD, etc. | Gene silencing tools to knock down specific antioxidant or regulatory components. | Establishing the causal role of a specific antioxidant protein in a phenotypic response. |

| Antibodies for Nrf2, Keap1, HO-1, NQO1, SOD, etc. | Used in Western Blot and Immunofluorescence to assess protein expression, localization (e.g., Nrf2 nuclear translocation), and degradation [22]. | Confirming pathway activation and target protein induction in treated cells or tissues. |

| Urease-IN-16 | Urease-IN-16, MF:C14H17BN2O4S, MW:320.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DBCO-PEG3-Acid | DBCO-PEG3-Acid, MF:C28H32N2O7, MW:508.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The enzymatic antioxidants SOD, catalase, and GPx form an indispensable, coordinated network that constitutes the body's primary defense against ROS. Their function is deeply integrated with non-enzymatic systems like glutathione and thioredoxin, and their expression is dynamically regulated by master transcription factors like Nrf2. A sophisticated understanding of these systems—from their basic chemistry to their complex regulation and the experimental tools used to study them—is fundamental for advancing redox biology research. This knowledge is directly translatable, providing a rational basis for developing novel therapeutics that target oxidative stress in aging, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic syndrome, and cancer by augmenting the body's innate antioxidant defenses.

Redox signaling is a fundamental biological process in which reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other reactive molecules act as deliberate messengers to modulate cellular functions, rather than solely as agents of damage [8] [24]. This signaling is integral to normal physiology, influencing processes ranging from endothelial cell growth to stress adaptation [24]. The core principle of redox signaling involves the specific, reversible chemical modification of target proteins, predominantly on cysteine residues, which alters their activity, interaction partners, and subcellular localization [24] [25] [26]. This stands in contrast to the traditional view of ROS as merely toxic byproducts.

The "Redox Code," a conceptual framework established in 2015, encapsulates the organizing principles for biological redox circuits. It encompasses the regulation of NADH and NADPH systems in metabolism, the dynamic control of thiol switches in the redox proteome, the activation and deactivation cycles of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production, and the multi-level response of redox signaling to environmental changes [8]. This code provides the foundational logic for understanding how redox signaling influences health and disease, offering a new perspective for identifying therapeutic targets.

Core Chemical Principles of Thiol-Based Redox Signaling

The Unique Reactivity of Protein Cysteines

Cysteine is one of the least abundant but most highly conserved amino acids in proteins, indicative of its critical functional roles [27]. Its sulfur-containing thiol group (-SH) is the key to its reactivity. A pivotal determinant of this reactivity is the thiol-thiolate equilibrium; the deprotonated thiolate form (-Sâ») is a much more powerful nucleophile than the protonated thiol [24] [27]. The propensity of a cysteine thiol to ionize is governed by its acid dissociation constant (pKâ‚). While the typical pKâ‚ for a cysteine in solution is approximately 8.3, the protein microenvironment can significantly lower this value, stabilizing the thiolate and enhancing reactivity [24] [28]. Factors such as proximity to positively charged amino acids, location within an alpha-helix dipole, and hydrogen-bonding networks can all contribute to this pKâ‚ perturbation [27].

This specialized chemistry means that redox signaling depends not on an abundance of cysteine residues, but on the presence of specific, strategically positioned cysteines with enhanced reactivity [24]. These reactive cysteines serve as molecular sensors for redox-active messengers.

Specificity, Kinetics, and Location in Signaling

For a molecule as potentially promiscuous as Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to function as a specific signal, stringent biochemical constraints are in place:

- Specificity: Signaling depends on specific cysteines within sensor proteins that have evolved to be highly reactive towards particular electrophiles due to their unique microenvironments [24].

- Kinetics: The rate of reaction between an electrophilic second messenger (e.g., Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) and its protein target is determined by the second-order rate constant and the concentrations of both partners. Reactive sensor cysteines possess rate constants that are several orders of magnitude higher than those of bulk cellular thiols [24] [27].

- Location: The generation of redox messengers like Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ is compartmentalized, creating steep concentration gradients from the source. Effective signaling requires the target protein to be in close proximity to the source of the ROS, allowing for specific modification before the messenger is scavenged by antioxidant systems [24].

These principles ensure that redox signaling is a precise and regulated process, not a stochastic one.

The Cysteine Modification Landscape

The thiolate form of reactive cysteines is susceptible to a spectrum of oxidative post-translational modifications (OxiPTMs). These modifications form a complex language, the "redox code," that cells use to transmit information [8] [29] [26].

Table 1: Major Reversible Cysteine Oxidative Modifications

| Modification | Inducing Agent(s) | Chemical Structure | Functional Consequences & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Sulfenylation | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, ROOH | -SOH | Highly reactive intermediate; often leads to disulfide formation or glutathionylation [25] [28]. |

| Disulfide Bond | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, via sulfenic acid | -S-S- (intra/intermolecular) | Can alter protein structure/activity; key in oxidative protein folding [25] [29]. |

| S-Glutathionylation | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, via sulfenic acid | -SSG (mixed disulfide with GSH) | Protects cysteine from over-oxidation; can regulate activity (e.g., actin polymerization) [8] [29] [28]. |

| S-Nitrosylation | Nitric oxide (•NO), ONOO¯ | -SNO | Regulates a wide range of proteins; important in vascular and neural signaling [3] [29] [26]. |

| Persulfidation | Hâ‚‚S | -SSH | Provides protection from irreversible oxidation; can regulate abscisic acid signaling in plants [25] [26]. |

The following diagram illustrates the dynamic network of reversible cysteine modifications and their interconversions, driven by different reactive species.

Beyond the modifications listed in the table, cysteine residues can undergo further oxidation to sulfinic (-SO₂H) and sulfonic (-SO₃H) acids. Sulfinic acid can be reversed by the ATP-dependent enzyme sulfiredoxin, while sulfonylation is typically considered irreversible and often associated with pathological damage [25].

The Redox Code in Physiology and Disease

Regulation of Genomic Stability

Redox signaling plays a critical role in maintaining genomic integrity. Oxidative stress can directly cause DNA damage, such as missense mutations and double-strand breaks (DSBs) [8]. More subtly, redox signaling finely regulates the DNA repair machinery itself through the oxidative modification of key proteins. For instance, the activation of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, a master regulator of the DNA damage response, is triggered by the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) complex and involves autophosphorylation, a process potentially regulated by the redox environment [8]. The precise redox modification of DNA repair proteins represents a crucial layer of control over genomic stability.

Implications in Neurodegeneration and Aging

The brain's high metabolic rate and relatively less robust antioxidant defenses make it particularly vulnerable to redox dysregulation [29]. In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), oxidative modifications of cysteine-sensitive proteins contribute to hallmark pathologies such as protein misfolding and aggregation [29]. The network of redox-modified proteins, sometimes termed the "cysteinet," is profoundly altered in these conditions, driving neuronal dysfunction [29].

The role of redox signaling in aging is complex and dualistic. While the long-held "free radical theory" posits aging as a result of accumulated oxidative damage, emerging evidence suggests that a mild, transient increase in ROS can activate adaptive signaling pathways that promote longevity [3] [25]. For example, interventions like dietary restriction and reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling, which extend lifespan in model organisms, are associated with altered redox profiles and depend on specific redox-sensitive proteins [25]. This highlights that the goal of therapeutic intervention is not blanket antioxidant suppression, but the targeted restoration of healthy redox signaling.

Research Methodologies and Experimental Analysis

Deciphering the redox code requires specialized tools to detect, quantify, and functionally characterize cysteine OxiPTMs within the complex cellular environment.

Key Experimental Workflows

A generalized proteomic workflow for analyzing cysteine oxidation involves several critical stages, from cell preparation to functional validation, as outlined below.

This workflow allows for the proteome-wide identification of specific cysteine modifications. For example, the "biotin-switch technique" and its modern derivatives are cornerstone methods for detecting S-nitrosylation and other reversible modifications [30].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

A successful investigation into redox signaling relies on a toolkit of specific reagents and model systems.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Models for Redox Signaling Research

| Category / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Thiol-Blocking Agents (N-ethylmaleimide, Iodoacetamide) | Alkylates and blocks free thiols to prevent post-lysis oxidation artifacts. | Used in initial step of chemoproteomic workflows to "lock in" the redox state [30]. |

| Selective Reducing Agents (Ascorbate, Arsenite) | Selectively reduces specific OxiPTMs (e.g., Ascorbate for S-nitrosylation). | Allows for selective tagging and enrichment of specific modification types [30]. |

| Affinity Tags (Biotin-HPDP, Isotope-coded affinity tags - ICAT) | Tags reduced thiols for purification and quantification via mass spectrometry. | Enables purification and relative quantification of redox-modified peptides [30]. |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors (roGFP, HyPer) | Fluorescent proteins that change emission/intensity upon redox change or Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ binding. | Real-time, compartment-specific monitoring of redox dynamics in live cells [25]. |

| Model Organisms (C. elegans, Mice with altered antioxidant genes) | In vivo systems to study the physiological role of redox signaling in aging/disease. | Identifying pro-longevity pathways activated by mild ROS [25]. |

Functional validation is the final and crucial step. This typically involves site-directed mutagenesis, where a redox-sensitive cysteine is replaced with a redox-insensitive residue like serine or alanine (to disrupt signaling) or sometimes aspartate (to mimic a constitutively oxidized state) [25]. The functional consequences of these mutations are then assessed using biochemical and cellular assays to establish a causal link between the specific cysteine modification and the observed biological outcome.

The study of redox signaling has evolved from a focus on oxidative damage to an appreciation of a sophisticated language of chemical modifications that govern cellular function. The principles of thiol switching, cysteine modifications, and the overarching Redox Code provide a framework for understanding how cells sense and respond to their metabolic and environmental status. The compartmentalized, specific, and reversible nature of these processes underscores their role as critical physiological regulators.

Future research will continue to expand the "thiol redox proteome," identifying new sensor proteins and delineating the complex networks they form [30]. A major challenge and opportunity lie in translating this fundamental knowledge into therapeutic strategies. Instead of non-specific antioxidants, the next generation of therapeutics will likely involve small molecule inhibitors or inducers that target specific redox-sensitive nodes in signaling pathways to re-establish redox balance in diseases like cancer, neurodegeneration, and age-related disorders [8]. Achieving this goal will require a deep, context-specific understanding of the redox code, combining chemical proteomics, systems biology, and functional genomics to unlock its full therapeutic potential.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), have emerged as crucial physiological mediators in cellular signaling networks. Once considered solely as damaging agents, ROS are now recognized as fundamental second messengers that regulate processes including proliferation, differentiation, and metabolic adaptation [31] [32]. Among ROS, Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ best fulfills the requirements of a second messenger due to its relative stability, ability to diffuse across membranes, and enzymatic production and degradation that provide specificity for time and place [31]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms of ROS-mediated signaling, focusing on their roles in cellular fate decisions and the experimental frameworks for their investigation.

The "redox code" represents an organizational framework for biological operations where Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ plays a central role in spatiotemporal sequencing of differentiation and cellular life cycles through kinetically controlled redox switches [6]. These switches predominantly involve reversible oxidation of cysteine residues in target proteins, analogous to phosphorylation events in kinase-mediated signaling cascades [33]. The dual role of ROS as both essential signaling molecules and potential damaging agents creates a sophisticated regulatory system maintained through precise balance between production and elimination [34] [32].

Molecular Mechanisms of ROS-Mediated Signaling

Biochemical Basis of ROS Signaling

ROS signaling occurs primarily through specific, reversible oxidation of redox-sensitive cysteine residues in target proteins, particularly through sulfenic acid (-SOH) formation, which can progress to disulfide bonds or higher oxidation states [31] [34]. This oxidative modification alters protein structure, activity, and interaction networks, enabling propagation of redox signals throughout the cell [33].

Table 1: Principal Reactive Oxygen Species in Cellular Signaling

| ROS Species | Chemical Symbol | Reactivity | Stability | Primary Sources | Main Signaling Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide anion | O₂•⻠| Moderate | Low | Mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes | Precursor to H₂O₂, limited direct signaling |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Selective | High | SOD activity, NOX enzymes | Primary redox messenger |

| Hydroxyl radical | •OH | Extreme | Very low | Fenton reaction | Minimal signaling, mainly damage |

| Singlet oxygen | ¹O₂ | High | Low | Photosensitization | Limited evidence for physiological signaling |

The specificity of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ signaling is achieved through several mechanisms: (1) localized production by activated enzymes; (2) kinetic competition between peroxide-eliminating and peroxide-utilizing proteins; and (3) reversible oxidation of specific cysteine residues with particular microenvironments that lower their pKâ‚, making them more susceptible to oxidation [31] [5]. Peroxiredoxins (Prxs) play a particularly important role as both regulators and transducers of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ signals through their own redox state, creating redox relays that transmit oxidizing equivalents to target proteins [34] [6].

Key Signaling Pathways Regulated by ROS

Multiple developmentally significant signaling pathways are modulated by ROS through oxidative modification of crucial components:

- NRF2/KEAP1 Pathway: ROS-induced modification of specific cysteine residues on KEAP1 disrupts NRF2 degradation, enabling NRF2 translocation to the nucleus where it activates cytoprotective genes involved in antioxidant response and metabolism [32].

- NF-κB Pathway: ROS modulate this central inflammatory pathway, though the precise mechanisms remain context-dependent, influencing both activation and inhibition [32].

- PI3K/AKT Pathway: Redox regulation of phosphatases that counterbalance this growth and survival pathway represents an important mechanism for controlling proliferation [32].

- MAPK Pathways: Multiple MAPK family members are sensitive to cellular redox state, connecting ROS signals to proliferation, differentiation, and stress response decisions [32].

The diagram below illustrates the core mechanism of redox signaling through cysteine oxidation:

ROS in Cellular Processes: Proliferation, Differentiation, and Metabolism

Regulation of Stem Cell Fate

ROS function as a "rheostat" in stem cells, translating metabolic and environmental cues to coordinate cellular responses including self-renewal, differentiation, and quiescence [32]. Different stem cell types maintain distinct ROS set points:

- Hematopoietic Stem Cells (HSCs): Lower ROS levels are associated with greater potency and quiescence, while increased ROS promote differentiation [35] [32].

- Neural Stem Cells (NSCs): ROS accumulation controls proliferation and self-renewal, with moderate increases promoting maintenance of the stem cell pool [32].

- Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): These cells demonstrate a dual role for ROS, where the undifferentiated state correlates with lower ROS levels, but self-renewal requires ROS upregulation [32].

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) exhibit a unique metabolic configuration favoring glycolysis over oxidative phosphorylation, which maintains lower ROS levels and supports self-renewal by preventing oxidative stress-induced differentiation [35]. The transition to differentiated states involves a metabolic shift toward oxidative metabolism with coordinated increases in ROS that drive gene expression programs supporting specialized functions.

Metabolic Regulation and Signaling

ROS and cellular metabolism exist in a reciprocal relationship: metabolic activity generates ROS, which in turn regulate metabolic pathways through signaling functions [32]. Mitochondria serve as both major sources of ROS and key targets of redox regulation, creating feedback loops that adjust energy production to cellular needs.

Table 2: Major Cellular Sources of ROS and Their Regulation

| Source | Location | Primary ROS | Regulators | Role in Signaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I, Mitochondria | Mitochondrial matrix | O₂•⻠| NADH/NAD⺠ratio, RET | Metabolic sensing, hypoxic response |

| Complex III, Mitochondria | Intermembrane space | O₂•⻠| ΔΨm, UCP proteins | Glucose sensing, apoptosis |

| NADPH Oxidases (NOX) | Plasma membrane | O₂•â», Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Growth factors, cytokines | Receptor-mediated signaling |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | ER lumen | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Protein folding load | Unfolded protein response |

| Peroxisomes | Peroxisomal matrix | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Fatty acid oxidation | Lipid metabolism signaling |

Mitochondrial complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) represents a significant contributor to ROS generation, particularly through reverse electron transport (RET) when a high proton gradient coincides with abundant reduced ubiquinone [35]. This mechanism allows mitochondria to function as metabolic sensors, translating changes in energy state into redox signals that regulate gene expression and cell fate decisions.

The diagram below illustrates how ROS regulate key cellular fate decisions:

Experimental Approaches for ROS Research

Methodologies for ROS Detection and Measurement

Accurate assessment of ROS presents significant challenges due to their reactive nature, low concentrations, and compartmentalized production. Current guidelines emphasize the importance of specifying the particular ROS species being measured rather than treating "ROS" as a single entity [5].

Table 3: Experimental Approaches for ROS Measurement

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | ROS Detected | Key Considerations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical probes | DCFH-DA, DHE, Amplex Red | H₂O₂, O₂•⻠| Specificity issues, compartmentalization | General screening, extracellular H₂O₂ |

| Genetically encoded biosensors | roGFP, HyPer | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Subcellular targeting, ratiometric | Real-time intracellular monitoring |

| EPR/ESR spectroscopy | Spin traps (DMPO) | O₂•â», •OH | Direct detection, technical complexity | Specific radical identification |

| Oxidative damage markers | Protein carbonylation, 8-OHdG | Indirect | Downstream effects, not real-time | Cumulative oxidative stress |

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy with spin trapping represents the gold standard for specific radical identification, while genetically encoded sensors like roGFP and HyPer enable compartment-specific monitoring of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ dynamics in live cells [5]. For controlled ROS generation in experimental systems, researchers can use:

- Paraquat and quinones for O₂•⻠generation [5]

- MitoPQ for mitochondrial O₂•⻠generation [5]

- d-amino acid oxidase systems for controlled Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ production [5]

- Glucose oxidase for extracellular Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ generation [5]

Modulation of ROS Levels in Experimental Systems

To establish causal relationships between ROS and biological effects, researchers employ both pharmacological and genetic approaches:

- NOX inhibition: Specific inhibitors or genetic deletion of NOX components are preferred over non-specific inhibitors like apocynin or diphenyleneiodonium [5].

- Antioxidant systems: Modulation of SOD, catalase, or peroxiredoxin expression can reveal functions of specific ROS.

- Scavenging systems: Overexpression of catalase targeted to specific compartments can dissect location-dependent ROS effects.

The interpretation of antioxidant experiments requires careful consideration, as many commonly used "antioxidants" such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC) have multiple mechanisms beyond ROS scavenging, including effects on glutathione levels, protein disulfide reduction, and Hâ‚‚S generation [5].

The diagram below outlines a general experimental workflow for investigating ROS signaling:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for ROS Signaling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS generators | Paraquat, MitoPQ, d-amino acid oxidase systems | Controlled ROS production in specific compartments | MitoPQ targets mitochondria specifically |

| ROS sensors | DCFH-DA, MitoSOX, roGFP, HyPer | Detection and measurement of specific ROS | Genetically encoded sensors allow subcellular targeting |

| NOX inhibitors | GKT136901, VAS2870, NOX knockout models | Specific inhibition of NOX enzymes | Prefer specific inhibitors over apocynin |

| Antioxidant enzymes | Recombinant SOD, catalase, peroxiredoxins | Scavenging specific ROS species | Compartment-specific targeting needed |

| Thiol redox probes | Biotin-conjugated iodoacetamide, maleimide dyes | Detection of cysteine oxidation states | Enable redox proteomics approaches |

| ROS-activated prodrugs | Selenium-based Michael acceptor prodrugs | Selective drug release in high-ROS environments | Potential therapeutic applications |

| Vercirnon Sodium | Vercirnon Sodium, MF:C22H20ClN2NaO4S, MW:466.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| VCH-286 | VCH-286, MF:C34H50F2N4O3, MW:600.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Recent innovations include selenium-based prodrug strategies that leverage elevated ROS in pathological conditions for selective drug activation. These approaches utilize selenium ether derivatives that undergo Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-dependent elimination to release active Michael acceptor compounds, demonstrating potential for targeted therapies in cancer and inflammatory diseases [36].

ROS, particularly Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, function as sophisticated second messengers in the regulation of proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism through specific, reversible oxidation of protein targets. The compartmentalized production and elimination of ROS creates a signaling system that integrates metabolic state with cell fate decisions. Future research will continue to elucidate the specific molecular targets of ROS in different physiological contexts and develop increasingly precise tools for measuring and manipulating redox signaling. These advances hold promise for novel therapeutic approaches that target ROS signaling in cancer, degenerative diseases, and metabolic disorders.

Advanced Techniques for ROS Detection, Manipulation, and Pathway Analysis

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are inevitable byproducts of cellular aerobic metabolism that play a dual role in health and disease. At physiological levels, ROS function as crucial signaling molecules in cellular processes, while excessive generation leads to oxidative stress, biomolecular damage, and disease progression. The accurate detection and quantification of specific ROS is therefore paramount for understanding redox biology and its implications in various pathological conditions [3] [37]. The term "ROS" encompasses a spectrum of chemically distinct molecules including superoxide anion (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), hydroxyl radical (HO•), and others, each with unique reactivity, lifespan, and biological targets [5]. This technical guide comprehensively reviews state-of-the-art methodologies for ROS detection, with emphasis on probes, biosensors, and live-cell imaging approaches, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these technologies in investigative and drug development contexts.

Fundamental Chemistry and Biological Significance of ROS

Major Reactive Oxygen Species

ROS comprise both free radical and non-radical oxygen derivatives with diverse chemical properties and biological reactivities. The most biologically significant ROS include superoxide anion (O₂•â»), primarily generated through electron leakage from mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes I and III or via NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes; hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), produced through superoxide dismutation and functioning as a key redox signaling molecule; and the hydroxyl radical (HO•), an extremely reactive species generated via Fenton chemistry [3] [5]. Other biologically relevant species include peroxynitrite (ONOO¯), formed from the reaction between superoxide and nitric oxide, and hypochlorous acid (HOCl), produced by myeloperoxidase [3].

ROS Signaling and Oxidative Stress

ROS function as crucial signaling mediators at physiological concentrations, regulating processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and immune response through reversible oxidation of specific cysteine and methionine residues in target proteins [35] [37]. Hydrogen peroxide in particular serves as an important second messenger, with intracellular concentrations typically maintained in the low nanomolar range (1-100 nM) under homeostatic conditions [35]. When ROS production overwhelms cellular antioxidant capacity, oxidative stress occurs, leading to non-specific oxidation of proteins, lipids, and DNA, which contributes to aging, cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases [3] [37].

Advanced Methodologies for ROS Detection

Electrochemical Detection Systems