Redox Signaling in Inflammation and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of redox signaling's dual role in physiological homeostasis and the pathogenesis of chronic diseases.

Redox Signaling in Inflammation and Disease: Molecular Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targeting, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of redox signaling's dual role in physiological homeostasis and the pathogenesis of chronic diseases. It explores the molecular foundations of redox imbalance, detailing how oxidative and reductive stress regulate immune responses, inflammatory pathways, and contribute to neurological, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders. For researchers and drug development professionals, we examine cutting-edge methodological approaches for targeting redox-sensitive pathways, troubleshoot past failures of antioxidant therapies, and validate emerging biomarkers and Nrf2-focused strategies through comparative analysis of preclinical and clinical data. The synthesis offers a roadmap for developing precision medicine interventions that restore redox balance in inflammatory diseases.

The Molecular Landscape of Redox Signaling in Immune Regulation and Inflammation

Redox homeostasis, the delicate equilibrium between oxidative and reductive processes within biological systems, serves as a fundamental regulator of cellular function and signaling. While oxidative stress has been extensively studied for decades, emerging research reveals that reductive stress (RS)—the pathological overabundance of reducing equivalents—represents an equally critical disruption of redox balance with profound implications for inflammatory diseases and metabolic disorders. This technical review examines the molecular mechanisms governing redox homeostasis, detailing how bidirectional deviations contribute to disease pathogenesis through dysregulated immune responses, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired cellular signaling. We provide comprehensive experimental frameworks and quantitative assessments to equip researchers with methodologies for investigating both oxidative and reductive stress, emphasizing their interplay in chronic inflammation. The synthesized data and protocols presented herein aim to facilitate advanced research and therapeutic development targeting redox-based pathways in human disease.

Redox biology encompasses the complex network of reduction-oxidation reactions that underlie fundamental cellular processes, from energy metabolism to signal transduction. The term "redox" originates from the combination of "reduction" and "oxidation," describing chemical processes involving electron transfer between reactants [1]. Redox homeostasis represents the maintenance of optimal nucleophilic tone through continuous signaling for the production and elimination of electrophiles and nucleophiles [2]. This dynamic balance is not a static state but rather a continuously regulated process essential for healthy physiological functioning.

The clinical significance of redox homeostasis extends across numerous disease states. In cardiovascular diseases, dysregulated redox signaling facilitates persistent reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation that drives pathological feedback loops, contributing to an estimated increase in global cardiovascular deaths from 20.5 million in 2025 to approximately 35.6 million by 2050 [3]. Similarly, in chronic inflammatory conditions, redox imbalance creates a synergistic pathogenic loop that sustains inflammation through continuous activation of immune cells and pro-inflammatory signaling pathways [4]. The field of Quantitative Redox Biology has emerged to address the need for absolute quantitative information on all redox-active compounds, thermodynamic parameters, and kinetic data necessary to model these complex biological systems [5].

Traditional research has predominantly focused on oxidative stress, characterized by excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that overwhelm antioxidant defenses. However, robust evidence now highlights that reductive stress—the pathological shift toward an excessively reduced cellular state—plays an equally critical role in disease pathogenesis, particularly in metabolic and cardiovascular disorders [6] [7]. This review examines both extremes of the redox spectrum, their interconnected roles in inflammatory pathways, and the experimental approaches essential for their investigation.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

The Redox Spectrum: From Oxidative to Reductive Stress

The redox state of a cell exists on a spectrum, with oxidative stress and reductive stress representing opposing pathological extremes that disrupt normal physiological signaling:

Oxidative Stress (OS): A state characterized by an overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that overwhelms antioxidant defenses, leading to potential damage to cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and DNA [4]. ROS include superoxide anions (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), while RNS encompass nitric oxide (NO•) and peroxynitrite (ONOOâ») [4] [3].

Reductive Stress (RS): "A shift in the cellular redox balance towards a more reduced state, characterized by an excess of endogenous reductants (such as NADH, NADPH, and GSH) over their oxidized counterparts (NAD+, NADP+, and GSSG)" [7]. This excessively reduced state disrupts normal redox signaling, impairs mitochondrial function, and triggers endoplasmic reticulum stress [6].

Redox Homeostasis: The maintenance of nucleophilic tone through continuous feedback mechanisms that preserve the balance between oxidants and nucleophiles, representing the optimal physiological steady state for cellular function [2].

Quantitative Redox Principles

The field of Quantitative Redox Biology emphasizes precise measurement of redox parameters to enable accurate comparison across experimental systems. A fundamental quantitative relationship is described by the Nernst equation for the GSSG/2GSH couple, the major cellular redox buffer:

Where Eₕc represents the half-cell reduction potential. This equation demonstrates why absolute concentrations matter—a cell with 10 mM GSH requires a [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio of only 16.6 to achieve an Eₕc of -228 mV, while a cell with 1 mM GSH requires a ratio of 166 to achieve the same potential [5]. This quantitative approach reveals that the biological state of cells (proliferation, quiescence, differentiation, or cell death) correlates with specific redox environments, with proliferating cells exhibiting a more reduced state than differentiated cells [5].

Table 1: Characteristic Redox Environments Across Biological States

| Biological State | GSH/GSSG Ratio | Reduction Potential (Eâ‚•c) | Cellular Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation | High (≥166:1 in low GSH cells) | More reduced (-228 mV or lower) | Associated with superoxide signaling |

| Quiescence | Moderate | Intermediate (-228 to -200 mV) | Associated with hydrogen peroxide signaling |

| Differentiation | Lower than proliferating state | More oxidized | Stable functional state |

| Apoptosis | Significantly decreased | Oxidized (-180 to -150 mV) | Initiates programmed cell death |

| Necrosis | Drastically decreased | Highly oxidized | Results from severe oxidation |

Molecular Mechanisms of Redox Imbalance

Oxidative Stress in Inflammation

Oxidative stress represents a key pathogenic element in the pathophysiology of chronic inflammatory diseases, establishing a synergistic relationship that creates a pathogenic loop sustaining chronic inflammation [4]. This dynamic has been extensively documented in atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, inflammatory bowel diseases, and rheumatoid arthritis [4].

The molecular mechanisms through which OS drives inflammation include:

NF-κB Activation: ROS activate IκB kinase (IKK), leading to phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of IκB proteins, which frees NF-κB to translocate to the nucleus and promote transcription of pro-inflammatory genes encoding cytokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes like COX-2 and iNOS [4].

MAPK Pathway Activation: ROS inhibit MAPK phosphatases by oxidizing their catalytic cysteine residues, thereby prolonging MAPK signaling, particularly the p38 MAPK branch, which stabilizes mRNAs of inflammatory mediators and modulates chromatin accessibility [4].

Inflammasome Activation: ROS are essential for activating the NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, a multiprotein complex responsible for cleaving pro-caspase-1 into its active form, which subsequently activates interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, key cytokines in inflammatory propagation [4].

The major cellular sources of ROS include mitochondrial complexes I and III of the electron transport chain, NADPH oxidases (NOX1-5, DUOX1/2), uncoupled nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms, xanthine oxidase, and enzymes involved in endoplasmic reticulum oxidative protein folding [4] [3].

Reductive Stress in Metabolic and Inflammatory Disorders

Reductive stress has emerged as a critical pathway in metabolic disorders induced by overnutrition, with significant implications for cardiovascular health [6] [7]. The pathological mechanisms of RS include:

Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Excessive NADH accumulation disrupts mitochondrial function by impairing the electron transport chain, leading to decreased ATP production and paradoxically increased production of reactive oxygen species [7].

Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress: An excess of reductive equivalents in the ER hampers proper protein folding by disrupting disulfide bond formation, triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR), which can lead to insulin resistance and compromised cellular homeostasis [7].

Paradoxical Pro-inflammatory Effects: While traditionally viewed as opposing oxidative stress, chronic reductive stress can paradoxically sustain inflammatory responses by altering redox-sensitive signaling pathways, including modulation of NF-κB activity, thereby contributing to disease progression in autoimmune, cardiovascular, and neuroinflammatory disorders [4].

Antioxidant Exacerbation: Excessive antioxidant supplementation can further shift the redox balance toward reductive stress, potentially undermining the beneficial effects of exercise, impairing cardiovascular health, and aggravating metabolic disorders, particularly in obese individuals [7].

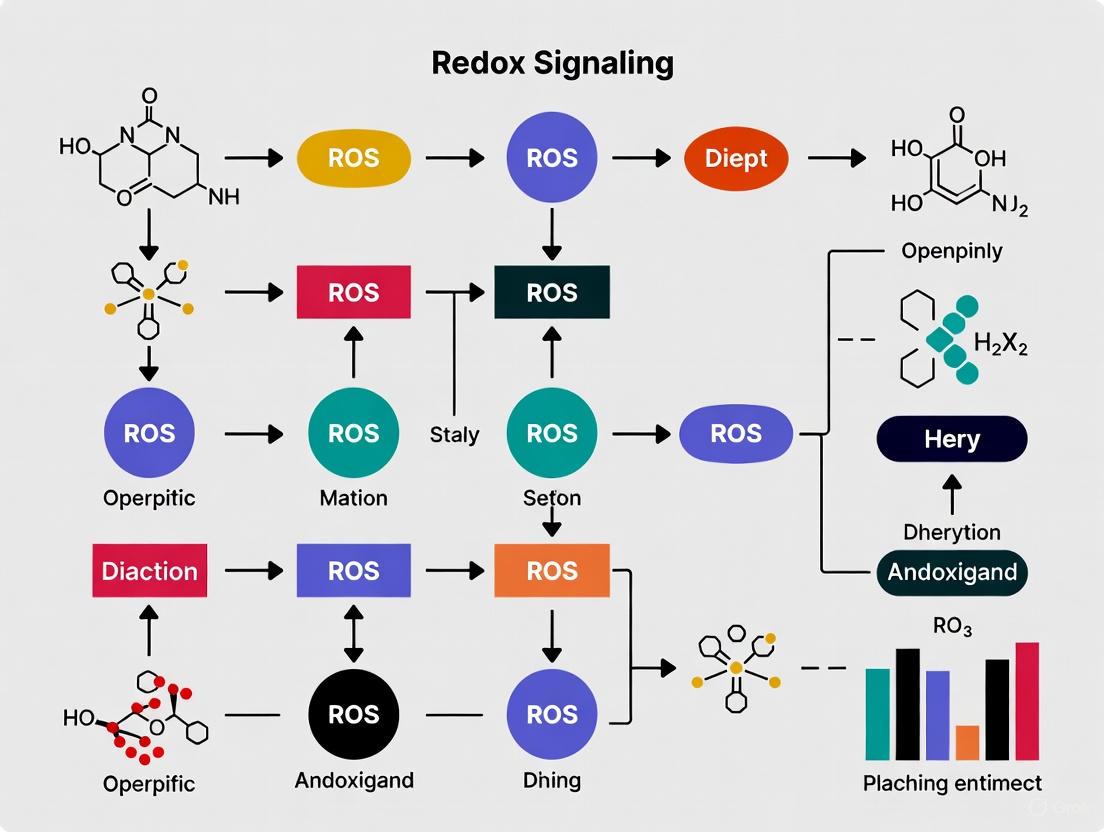

The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathways and pathological consequences of both oxidative and reductive stress:

Figure 1: Signaling Pathways in Oxidative and Reductive Stress

Experimental Approaches and Assessment Methodologies

Quantitative Assessment of Redox States

Accurate measurement of redox parameters requires standardized quantitative approaches. The following methodologies provide comprehensive assessment of redox status:

Glutathione Homeostasis Quantification:

- Sample Preparation: Deproteinize cell lysates or tissue homogenates using metaphosphoric acid or perchloric acid

- GSH Measurement: Derivatize with monobromobimane followed by HPLC separation with fluorescence detection

- GSSG Measurement: Mask GSH with 2-vinylpyridine before derivatization and HPLC analysis

- Calculation: Apply Nernst equation to determine reduction potential (Eâ‚•c) using absolute concentrations [5]

NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples:

- Enzyme Cycling Assays: Utilize specific dehydrogenases coupled to colorimetric or fluorescent reporters

- Separation Methods: HPLC or LC-MS for direct quantification of oxidized and reduced forms

- Critical Ratios: Calculate NADH/NAD+ and NADPH/NADP+ ratios as indicators of reductive stress [6] [7]

Redox-Sensitive GFP (roGFP) Imaging:

- Genetically encoded sensors targeted to specific cellular compartments

- Ratiometric fluorescence measurements for quantitative assessment

- Real-time monitoring of redox dynamics in living cells [5]

Table 2: Comprehensive Redox Assessment Parameters and Methodologies

| Parameter | Methodology | Physiological Range | Pathological Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSH/GSSG Ratio | HPLC with fluorescence detection | 166:1 (in 1 mM GSH cells) for Eâ‚•c -228 mV | Decreased in OS (<100:1); Increased in RS (>300:1) |

| NADH/NAD+ Ratio | Enzyme cycling assays or LC-MS | Varies by compartment | >0.01 in cytoplasm indicates RS |

| NADPH/NADP+ Ratio | Enzyme cycling assays or LC-MS | ~100:1 in cytoplasm | Significant elevation in RS |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Steady-State | roGFP or HyPer probes | 1-10 nM in cytoplasm | Elevated in OS (>100 nM) |

| Protein Sulfenylation | Dimedone-based probes | Baseline tissue-specific modifications | Widespread increase in OS |

| Mitochondrial Membrane Potential | TMRM or JC-1 staining | Cell type dependent | Hyperpolarization in RS |

Induction Models for Redox Studies

Experimental Models of Reductive Stress:

- Pharmacological Induction: Treatment with compounds like sulforaphane or glutathione ethyl ester (GEE) to boost cellular reducing capacity [6]

- Genetic Models: Expression of human R120G mutant αB-crystallin (hR120G cryAB) known to induce reductive stress [6]

- Metabolic Loading: High-glucose conditions or fatty acid oversupply to increase reducing equivalent generation [7]

Experimental Models of Oxidative Stress:

- Pharmacological Induction: Treatment with paraquat, menadione, or buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) [1]

- Genetic Models: Knockdown of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, GPx, catalase) [5]

- Physiological Stimuli: Hypoxia-reoxygenation, cytokine stimulation, or NOX activation [4]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Redox Biology Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Mechanistic Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Inducers | Paraquat, Menadione, BSO | Experimental OS models | Generate superoxide or deplete GSH |

| RS Inducers | GSH ethyl ester (GEE), NAC, Sulforaphane | Experimental RS models | Boost cellular reducing capacity |

| NADH Modulators | NR (Nicotinamide riboside) | Manipulate NADH/NAD+ ratio | Precursor for NAD+ biosynthesis |

| Mitochondrial Probes | TMRM, JC-1, MitoSOX | Assess membrane potential and mtROS | Potential-sensitive distribution |

| Genetic Tools | shRNA against SOD, NOX isoforms, roGFP constructs | Targeted pathway manipulation | Specific pathway modulation |

| Redox Biosensors | roGFP, HyPer, Grx1-roGFP | Quantitative live-cell imaging | Ratiometric redox measurement |

| Thiol Status Assays | Monobromobimane, DTNB | Quantify thiol oxidation | Thiol-reactive compounds |

| Antioxidant Enzymes | Recombinant SOD, CAT, GPx | Supplemental antioxidant defense | Scavenge specific ROS |

| 1,2-O-Cyclohexylidene-myo-inositol | 1,2-O-Cyclohexylidene-myo-inositol, MF:C12H20O6, MW:260.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-Fluorophenylboronic acid | 2-Fluorophenylboronic Acid | High Purity RUO | 2-Fluorophenylboronic acid for Suzuki cross-coupling. High purity, for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Research Gaps and Future Directions

The emerging recognition of reductive stress as a significant pathological state has revealed several critical research gaps that warrant investigation:

Threshold Determination: Precise quantitative thresholds for pathological reductive stress across different tissue types and disease states remain undefined [4] [5].

Dual-Role Proteins: The context-dependent functions of factors like Nrf2, which can exhibit both protective and potentially detrimental effects depending on the duration and intensity of activation, require clarification [4] [1].

Spatiotemporal Dynamics: Advanced technologies are needed to resolve redox dynamics with high spatial and temporal resolution to understand compartment-specific redox regulation [3] [5].

Antioxidant Therapy Refinement: The paradoxical effects of antioxidant interventions, which may exacerbate reductive stress in certain contexts, necessitate the development of more precise, targeted approaches that consider the bidirectional nature of redox dysregulation [4] [7] [1].

Future research should prioritize the development of disease-specific redox profiling and biomarker panels that can distinguish between oxidative and reductive stress components in clinical samples, enabling personalized redox-based therapeutics.

Redox homeostasis represents a critical determinant of cellular health, with both oxidative and reductive stress contributing significantly to inflammatory pathogenesis and metabolic disorders. The traditional antioxidant-centric view of redox balance requires expansion to incorporate the emerging understanding of reductive stress as a distinct pathological entity. Comprehensive investigation of redox processes demands rigorous quantitative approaches, precise compartment-specific assessment, and integrated analysis of the interconnected networks that maintain redox equilibrium. The experimental frameworks and methodological tools presented in this review provide a foundation for advancing research in redox biology, with particular relevance for understanding inflammatory disease mechanisms and developing targeted therapeutic interventions that restore redox homeostasis without inducing pathological extremes in either direction.

Redox signaling represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism in cellular biology, governing processes from metabolism to gene expression. The term "redox" originates from "reduction" and "oxidation," describing chemical processes involving electron transfer between reactants [1]. Within physiological systems, reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), and reactive sulfur species (RSS) function as crucial signaling mediators, maintaining cellular homeostasis at low concentrations but driving pathological processes when dysregulated [8] [3] [1]. The delicate balance between oxidative and reductive forces constitutes redox homeostasis, where disruption—termed oxidative stress or reductive stress—forms a common pathway in the pathogenesis of diverse inflammatory, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and metabolic diseases [4] [1]. This review comprehensively examines the dual nature of key reactive species, their signaling mechanisms, measurement methodologies, and therapeutic targeting within inflammation and disease research contexts.

Classification and Properties of Key Reactive Species

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS are oxygen-containing molecules characterized by highly reactive unpaired electrons [9]. They are broadly categorized into radical and non-radical species, generated endogenously as metabolic byproducts and exogenously from environmental exposures [10] [9].

Table 1: Major Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

| Category | Species | Chemical Formula | Reactivity | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radical ROS | Superoxide anion | O₂•⻠| Moderate | Mitochondrial ETC, NADPH oxidases |

| Hydroxyl radical | •OH | Very high | Fenton reaction | |

| Alkoxyl radical | RO• | High | Lipid peroxidation | |

| Peroxyl radical | ROO• | High | Lipid peroxidation | |

| Non-radical ROS | Hydrogen peroxide | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Moderate | Superoxide dismutation |

| Singlet oxygen | ¹O₂ | High | Photosensitization reactions | |

| Hypochlorous acid | HOCl | High | Myeloperoxidase activity | |

| Ozone | O₃ | High | Exogenous source |

Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS)

RNS are nitrogen-containing radicals and non-radicals derived primarily from nitric oxide (NO•) and its reaction products [3] [9]. Nitric oxide, synthesized by nitric oxide synthases (NOS), plays vital roles in vascular regulation, neurotransmission, and immune responses [9].

Table 2: Major Reactive Nitrogen Species (RNS)

| Category | Species | Chemical Formula | Reactivity | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Radical RNS | Nitric oxide | NO• | Moderate | NOS enzymes |

| Nitrogen dioxide | NO₂• | High | Peroxynitrite decomposition | |

| Non-radical RNS | Peroxynitrite | ONOO⻠| Very high | NO• + O₂•⻠reaction |

| Nitrous acid | HNOâ‚‚ | Moderate | Acidification of nitrite | |

| Nitroxyl anion | NOâ» | Moderate | NO metabolism | |

| Dinitrogen trioxide | N₂O₃ | High | NO• + NO₂• reaction |

Reactive Sulfur Species (RSS)

RSS represent a rapidly emerging class of redox regulators, with hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) serving as a key signaling molecule [3]. RSS participate in protein post-translational modifications, particularly S-sulfhydration, which regulates numerous cellular processes including metabolism, mitochondrial function, vasodilation, and inflammatory responses [3]. The Hâ‚‚S donor, S-propyl-L-cysteine, demonstrates cardioprotective effects by improving mitochondrial dysfunction via S-sulfhydration of Ca²âº/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in heart failure models [3].

Compartmentalization of Reactive Species Production

Reactive species generation exhibits distinct subcellular compartmentalization, with specific organelles contributing differentially to the cellular redox landscape [8]. Mitochondria constitute the primary source of endogenous ROS, accounting for approximately 90% of cellular ROS production during oxidative phosphorylation [8]. Complexes I and III of the electron transport chain represent major sites of superoxide generation [3]. Additional significant sources include NADPH oxidases (NOX family enzymes) dedicated to regulated ROS production [8] [11], endoplasmic reticulum oxidative protein folding [4], peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation [8], and cytoplasmic enzymatic reactions involving xanthine oxidase and cytochrome P450 systems [8] [9].

Enzymatic Systems for Reactive Species Generation

The NADPH oxidase (NOX) family comprises seven homologs (NOX1-5, DUOX1/2) that catalyze superoxide production by transferring electrons from NADPH to molecular oxygen [3] [11]. These enzymes differ in tissue distribution, activation mechanisms, and biological functions, with NOX2 originally identified in phagocytes for microbial killing [11]. Nitric oxide synthases (NOS) generate NO• through oxidation of L-arginine, with three isoforms mediating neuronal signaling (nNOS), vascular regulation (eNOS), and inflammatory responses (iNOS) [9]. Xanthine oxidase produces superoxide during purine metabolism [4], while mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes generate ROS as byproducts of aerobic respiration [8] [3].

Diagram 1: Cellular Sources of Reactive Species. ROS are generated through multiple cellular compartments including mitochondrial electron transport, NADPH oxidase enzymes, endoplasmic reticulum protein folding, and peroxisomal metabolism.

Molecular Targets and Signaling Pathways

Redox-Sensitive Signaling Cascades

Reactive species function as signaling mediators through reversible oxidation of critical cysteine residues in target proteins, altering their structure, activity, and interaction networks [1]. Major redox-sensitive pathways include:

The NF-κB pathway represents a primary inflammatory signaling cascade regulated by ROS [4]. Under basal conditions, NF-κB dimers remain sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB proteins. ROS activate IκB kinase (IKK), leading to IκB phosphorylation and degradation, thereby releasing NF-κB for nuclear translocation and pro-inflammatory gene transcription [4]. Additionally, ROS inhibit MAPK phosphatases by oxidizing catalytic cysteine residues, prolonging MAPK signaling including JNK, p38, and ERK pathways that regulate inflammation, stress responses, and cell survival [4].

The Nrf2/KEAP1 axis constitutes a central antioxidant response system [4] [1]. Under homeostatic conditions, Nrf2 remains bound to KEAP1, targeting it for ubiquitination and degradation. Oxidative modification of critical cysteine residues on KEAP1 enables Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation, where it induces expression of cytoprotective genes including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), and glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) [4].

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) represents another redox-sensitive transcription factor that coordinates cellular adaptation to low oxygen tension [8] [4]. ROS stabilize HIF-1α by inhibiting prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing proteins (PHDs), enabling its dimerization with HIF-1β and transcription of genes promoting angiogenesis, metabolic adaptation, and cell survival [8].

Diagram 2: Redox-Sensitive Signaling Pathways. ROS activate multiple signaling cascades including NF-κB (inflammatory genes), Nrf2 (antioxidant genes), and MAPK (cell growth/differentiation genes).

Biomolecular Damage and Pathological Consequences

At elevated concentrations, reactive species inflict macromolecular damage through irreversible oxidation, contributing to cellular dysfunction and disease pathogenesis [12] [9]. Lipid peroxidation represents a particularly destructive process wherein ROS attack polyunsaturated fatty acids in cell membranes, initiating chain reactions that generate reactive aldehydes including malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) [9]. These products form adducts with proteins and DNA, impairing their function and propagating oxidative damage [9]. Protein oxidation modifies amino acid side chains (particularly cysteine and methionine), forms protein-protein crosslinks, and fragments peptide chains, leading to loss of enzymatic activity, disrupted signaling, and structural protein degradation [13] [9]. DNA damage includes base modifications (e.g., 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine), strand breaks, and crosslinking, resulting in mutations, genomic instability, and aberrant gene expression [9].

Table 3: Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Damage

| Target | Biomarker | Detection Methods | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids | Malondialdehyde (MDA) | TBARS assay, HPLC, GC-MS | Lipid peroxidation end product |

| 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) | HPLC, GC-MS/MS, immunoassays | Reactive aldehyde, protein adduct formation | |

| Fâ‚‚-isoprostanes | GC-MS, LC-MS, immunoassays | Gold standard for lipid peroxidation | |

| Proteins | Protein carbonyls | HPLC, immunoassays, Western blot | Protein oxidation marker |

| 3-Nitrotyrosine | LC/GC with various detectors, immunoassays | Protein nitration marker | |

| Advanced Oxidation Protein Products (AOPP) | Colorimetric assays, GC-MS | Protein damage in inflammatory diseases | |

| DNA | 8-OHdG | HPLC-EC, LC-MS, GC-MS, immunoassays | Oxidative DNA damage marker |

| 5-Hydroxymethyluracil | GC-MS | DNA oxidation product | |

| Overall Status | Total Antioxidant Capacity | Various colorimetric assays | Integrated antioxidant defense assessment |

Physiological Roles in Cellular Signaling

At low, physiological concentrations, reactive species function as crucial signaling mediators in numerous cellular processes [8]. ROS regulate cell proliferation and differentiation through reversible oxidation of protein tyrosine phosphatases and receptor tyrosine kinases, modulating growth factor signaling cascades [8]. The MAPK/ERK, PTK/PTP, and PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathways represent key redox-sensitive signaling networks controlling cell growth, survival, and metabolism [8]. In the immune system, ROS production by NADPH oxidase (NOX2) in phagocytes enables microbial killing through the respiratory burst, while simultaneously regulating immune cell activation and inflammatory responses [4] [11]. Reactive species also mediate apoptotic signaling, with mitochondrial ROS participating in intrinsic pathway activation and caspase regulation [14]. Vascular tone regulation involves NO•-mediated vasodilation and ROS modulation of endothelial signaling, while neuronal communication utilizes NO• as a neurotransmitter and ROS in synaptic plasticity [3] [9].

Pathological Implications in Disease

Oxidative Stress in Chronic Inflammation

Oxidative stress and chronic inflammation form a self-perpetuating cycle that drives disease pathogenesis across multiple organ systems [4] [11]. In cardiovascular diseases, ROS contribute to endothelial dysfunction, leukocyte recruitment, foam cell formation, and vascular remodeling in atherosclerosis [3] [11]. Myocardial infarction and heart failure involve ROS-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired contractility, and adverse remodeling [3]. Neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases feature oxidative damage to neurons, protein misfolding, and mitochondrial dysfunction that promote neuronal loss [13] [9]. Respiratory diseases such as COPD, asthma, and ARDS involve oxidative injury to lung epithelium, barrier dysfunction, and persistent inflammation [8] [13]. Autoimmune and metabolic disorders including rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and diabetes mellitus demonstrate sustained ROS production that amplifies tissue damage and dysfunction [8] [4].

The Emerging Concept of Reductive Stress

Recent evidence indicates that not only oxidative stress but also reductive stress (RS)—characterized by excessive reducing equivalents including NADH, NADPH, and reduced glutathione (GSH)—can disrupt redox homeostasis and contribute to disease [4]. RS arises from overactive antioxidant systems or metabolic alterations that increase reducing capacity, potentially impairing disulfide bond formation, altering redox-sensitive signaling, and compromising mitochondrial function [4]. Chronic reductive stress associates with certain cardiomyopathies, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndromes, demonstrating the importance of balanced redox regulation rather than simply maximizing antioxidant capacity [4].

Methodologies for Detection and Measurement

Experimental Approaches for Reactive Species Detection

Accurate measurement of reactive species and oxidative damage presents methodological challenges due to their reactivity, short half-lives, and low physiological concentrations [12]. Direct detection approaches include electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy for free radical identification and quantification, while fluorescent probes (e.g., DCFH-DA, DHE) enable cellular imaging of ROS with spatial and temporal resolution [12]. Chemiluminescence-based assays utilizing luminol or lucigenin provide sensitive detection of extracellular ROS production, particularly in immune cells [11]. Indirect assessment through oxidative damage biomarkers offers more stable analytical targets, with mass spectrometry-based methods (GC-MS, LC-MS/MS) providing gold-standard quantification of isoprostanes, 8-OHdG, and protein carbonyls [12]. Immunoassays enable high-throughput measurement of various oxidative stress markers in clinical and research settings [12].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Biology

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | DCFH-DA, DHE, MitoSOX | Cellular ROS detection | Site-specific (mitochondrial), redox-sensitive fluorescence |

| Chemical Scavengers | N-acetylcysteine, Tempol | Direct ROS quenching | Membrane-permeable antioxidants |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Apocynin, VAS2870 | NADPH oxidase inhibition | Specific targeting of ROS sources |

| Genetic Tools | siRNA, CRISPR/Cas9 | Knockdown/knockout of redox enzymes | Targeted manipulation of specific pathways |

| Activity Assays | Amplex Red, cytochrome c reduction | Enzymatic activity measurement | Quantification of NOX, XO, antioxidant enzymes |

| Antibody-based Reagents | Anti-3-nitrotyrosine, anti-HNE | Detection of oxidative modifications | Specific recognition of oxidized biomolecules |

Protocol for Measuring Lipid Peroxidation via TBARS Assay

The thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay represents a widely used method for assessing lipid peroxidation in biological samples [12]:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize tissue samples or collect cell lysates in phosphate-buffered saline containing butylated hydroxytoluene (0.01%) to prevent artificial oxidation during processing.

- Reaction Mixture: Combine 100μL sample with 200μL of 8.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1.5mL of 20% acetic acid (pH 3.5), and 1.5mL of 0.8% thiobarbituric acid.

- Incubation: Heat mixture at 95°C for 60 minutes, then cool on ice for 10 minutes.

- Extraction: Add 1mL of distilled water and 5mL of n-butanol:pyridine (15:1 v/v) mixture, vortex vigorously, and centrifuge at 1,500×g for 10 minutes.

- Measurement: Collect the organic layer and measure absorbance at 532nm against MDA standards (typically 1-20μM). Express results as nmol MDA equivalents per mg protein.

Protocol for Assessing Protein Carbonylation via DNPH Assay

Protein carbonylation serves as a reliable marker of protein oxidation [12]:

- Protein Precipitation: Add 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to sample (1:1 v/v), incubate on ice for 10 minutes, and centrifuge at 15,000×g for 5 minutes.

- Derivatization: Resuspend protein pellet in 500μL of 10mM 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) in 2M HCl (for sample) or 2M HCl alone (for blank control). Incubate for 60 minutes at room temperature with vortexing every 15 minutes.

- Precipitation and Washing: Precipitate protein with 20% TCA, wash pellet three times with 1mL ethanol:ethyl acetate (1:1 v/v) to remove free DNPH.

- Solubilization: Dissolve final pellet in 500-1000μL of 6M guanidine hydrochloride (pH 2.3) by incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes with occasional vortexing.

- Measurement: Measure absorbance at 370nm and calculate carbonyl content using molar extinction coefficient of 22,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹. Normalize to protein concentration.

Therapeutic Implications and Targeting Strategies

Antioxidant-Based Therapeutic Approaches

Traditional antioxidant strategies have focused on direct ROS scavenging using compounds such as vitamin C, vitamin E, N-acetylcysteine, and SOD mimetics [9] [1]. However, clinical trials with broad-spectrum antioxidants have yielded largely disappointing results, attributed to lack of specificity, inability to target relevant ROS sources, and disruption of physiological redox signaling [3] [1]. This has prompted development of more targeted approaches including NOX isoform-specific inhibitors that block pathological ROS production at its source [11], Nrf2 activators that boost endogenous antioxidant defenses [4] [1], and mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (e.g., MitoQ) that concentrate antioxidant capacity at major ROS generation sites [3].

Emerging Redox-Based Therapeutics

Contemporary drug development recognizes the need for nuanced redox modulation rather than blanket antioxidant suppression [1]. Emerging strategies include small molecule inhibitors targeting specific cysteine residues in redox-sensitive proteins [1], modulators of redox-sensitive transcription factors with contextual activity [4], and redox-based combination therapies that exploit oxidative vulnerabilities in specific disease states [3]. The bidirectional nature of redox imbalance necessitates therapeutic approaches that can address both oxidative and reductive stress depending on disease context [4]. Future directions include development of disease-specific redox biomarkers for patient stratification, smart antioxidants with activatable specificity, and nanoparticle-based delivery systems for targeted redox modulation [13] [1].

Diagram 3: Therapeutic Strategies for Redox Imbalance. Approaches include traditional antioxidants, targeted inhibitors of specific ROS sources, NRF2 activators boosting endogenous defenses, and mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants.

ROS, RNS, and RSS function as crucial signaling mediators in physiological processes while simultaneously driving pathological mechanisms when dysregulated. The dual nature of these reactive species necessitates precise homeostatic control rather than simple elimination. Future research directions should focus on spatiotemporal regulation of specific reactive species, development of targeted redox-based therapeutics, identification of clinically relevant redox biomarkers, and understanding of inter-organ communication in systemic redox regulation. As methodological advances enable more precise monitoring and manipulation of redox processes, the therapeutic targeting of reactive species promises novel interventions for inflammatory, cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and metabolic diseases.

Redox imbalance, a state of disrupted equilibrium between oxidant production and antioxidant defenses, is a pivotal regulator of inflammatory processes and the pathogenesis of numerous diseases [4]. While physiological levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) function as crucial signaling molecules, their dysregulation contributes to a spectrum of pathologies including cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and autoimmune disorders [4] [15] [16]. This technical guide examines three principal cellular sources of redox imbalance: mitochondria, NADPH oxidase (NOX) enzymes, and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Understanding the distinct mechanisms, interplay, and experimental approaches for investigating these sources is fundamental for developing targeted therapeutic strategies in inflammation-related disease research.

Mitochondria: The Metabolic Powerhouse as a Redox Signal Integrator

Mechanisms of Mitochondrial ROS Production

Mitochondria are fundamental organelles responsible for cellular bioenergetics, but他们也 represent a major endogenous source of ROS [17]. The electron transport chain (ETC) is the primary site for mitochondrial ROS generation, with complex I (NADH dehydrogenase) and complex III (ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase) identified as the most significant contributors [17]. Under normal physiological conditions, an estimated 1-2% of molecular oxygen consumed by mitochondria undergoes incomplete reduction, leading to the formation of superoxide anion (O₂•â») [17]. At complex I, O₂•⻠is produced primarily through the electron transfer to Oâ‚‚ during flavin mononucleotide semiquinone autoxidation. At complex III, O₂•⻠generation occurs via the ubiquinone cycle, where the semiubiquinone intermediate donates an electron to molecular oxygen [17]. The highly reactive O₂•⻠is rapidly converted to the more stable hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) by manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD/SOD2) in the mitochondrial matrix. Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, being membrane-permeable, can diffuse throughout the cell and function as a redox signaling molecule [4] [17].

Beyond the ETC, several other mitochondrial enzymes contribute to ROS production, including α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, pyruvate dehydrogenase, and enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation [17]. Under pathophysiological conditions such as hypoxia, metabolic overload, or mitochondrial DNA damage, electron leakage increases substantially, leading to excessive ROS production that overwhelms antioxidant defenses and promotes oxidative damage [17] [18].

Redox Signaling and Pathophysiological Consequences

Mitochondrial ROS function as important signaling molecules that regulate various cellular processes, including inflammatory responses, hypoxic signaling, and apoptosis [17]. However, chronic mitochondrial ROS overproduction disrupts redox-sensitive signaling pathways, particularly through the oxidation of critical cysteine residues in regulatory proteins [17]. In cardiovascular diseases, mitochondrial ROS contribute to endothelial dysfunction by reducing nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability through the formation of peroxynitrite (ONOOâ»), a potent oxidant and nitrating agent [15] [16]. In the context of intervertebral disc degeneration, mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS overproduction promote inflammatory cytokine production, extracellular matrix degradation, and cellular senescence [18]. Furthermore, mitochondrial ROS can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, leading to the maturation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-18 [4].

Table 1: Key Sites of Mitochondrial ROS Production and Their Characteristics

| Site/Enzyme | Primary ROS | Subcellular Location | Regulatory Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I | O₂•⻠| Mitochondrial matrix | High NADH/NAD+ ratio, reverse electron transport |

| Complex III | O₂•⻠| Mitochondrial intermembrane space | Antimycin A, ubiquinone pool redox state |

| α-Ketoglutarate dehydrogenase | O₂•⻠| Mitochondrial matrix | Substrate availability, Ca²⺠|

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase | O₂•⻠| Mitochondrial matrix | Pyruvate concentration, phosphorylation status |

| Fatty acid β-oxidation | H₂O₂ | Mitochondrial matrix | Fatty acid load, carnitine levels |

NADPH Oxidases: Purpose-Built ROS-Generating Enzymes

NOX Enzyme Family Structure and Function

The NADPH oxidase (NOX) family represents the only known enzyme family dedicated solely to deliberate ROS generation [19] [20]. Unlike mitochondrial ROS production, which occurs as a byproduct of metabolism, NOX enzymes catalyze the controlled reduction of molecular oxygen to generate O₂•⻠and/or H₂O₂ for specific signaling purposes [19]. The NOX family comprises seven members: Nox1-5 and Duox1-2, each with distinct tissue distribution, regulatory mechanisms, and subcellular localization [19]. All NOX isoforms share a common core structure consisting of six transmembrane domains containing two heme groups, and cytosolic C-terminal domains that bind FAD and NADPH [19] [20]. Electrons are transferred from NADPH through FAD and the heme groups to molecular oxygen, resulting in superoxide production [20].

Nox2 (originally identified as gp91phox) is highly expressed in phagocytic cells where it generates antimicrobial ROS, but it is also present in vascular cells including endothelial and smooth muscle cells [19]. Nox4, predominantly expressed in the kidney and vasculature, differs from other isoforms by producing H₂O₂ rather than O₂•⻠under most conditions [19]. Interestingly, subcellular localization studies of endogenous Nox4 in human endothelial cells show predominant nuclear localization, suggesting specific roles in nuclear redox signaling, though overexpression studies often show endoplasmic reticulum localization [19].

Regulation and Pathological Roles of NOX Enzymes

NOX enzyme activity is tightly regulated through multiple mechanisms, including transcriptional control, post-translational modifications, and interactions with regulatory subunits [19]. The vascular endothelium predominantly expresses Nox2 and Nox4, with Nox4 demonstrating constitutive activity while Nox2 requires activation by stimuli such as cytokines, growth factors, hyperoxia, and hypoxia [19]. In cardiovascular pathologies, angiotensin II significantly upregulates Nox1 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells, contributing to hypertension and vascular remodeling [19] [16].

NOX-derived ROS play critical roles in inflammatory signaling through the activation of redox-sensitive transcription factors including NF-κB and AP-1, which subsequently induce expression of adhesion molecules, cytokines, and chemokines that perpetuate inflammatory cascades [4] [19]. In chronic inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis, sustained NOX activation contributes to endothelial dysfunction, LDL oxidation, and monocyte recruitment [15] [16]. The development of isoform-specific NOX inhibitors represents an active area of therapeutic research for inflammatory and cardiovascular diseases [19] [16].

Diagram 1: NOX Enzyme Activation and Downstream Signaling

Endoplasmic Reticulum: Protein Folding and Redox Crossroads

ER Stress and Redox Imbalance

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a crucial organelle for protein synthesis, folding, and post-translational modifications [21] [22]. The ER lumen maintains a unique oxidizing environment necessary for disulfide bond formation, a process catalyzed by protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and ER oxidoreductase 1 (Ero1) [21]. During oxidative protein folding, electrons are transferred from cysteine thiols in substrate proteins through PDI and Ero1 to molecular oxygen, generating H₂O₂ as a byproduct [21] [18]. Under physiological conditions, this ROS production is minimal, but during ER stress – triggered by accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins – dysregulated disulfide bond formation leads to excessive ROS generation [21] [22].

ER stress activates an adaptive signaling network called the unfolded protein response (UPR), primarily through three transmembrane sensors: IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6 [21] [22]. Under normal conditions, these sensors are maintained in an inactive state through association with the ER chaperone BiP/GRP78. The accumulation of unfolded proteins causes BiP dissociation, leading to sensor activation [22]. Persistent or severe ER stress that cannot be resolved by the UPR transitions from adaptive to pro-apoptotic signaling, contributing to various pathological states [21] [22].

ER-Mitochondrial Crosstalk in Redox Signaling

A critical aspect of ER-related redox imbalance involves interorganellar crosstalk, particularly with mitochondria at specialized contact sites called mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) [21] [22]. Under ER stress conditions, calcium (Ca²âº) release from the ER leads to subsequent mitochondrial Ca²⺠uptake, which can stimulate mitochondrial ROS production [21] [18]. This creates a vicious cycle where ER stress-induced ROS promotes mitochondrial ROS, which further exacerbates ER stress [22]. Additionally, the UPR transducer IRE1α can activate JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways through interaction with TRAF2, thereby linking ER stress to inflammatory responses [22]. The transcription factor CHOP, induced during prolonged ER stress, downregulates antioxidant defenses and promotes oxidative damage [21] [22].

Table 2: Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Sensors and Their Redox Functions

| UPR Sensor | Activation Mechanism | Redox-Related Functions | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRE1α | Dimerization, trans-autophosphorylation, RNase activation | XBP1 splicing, RIDD, JNK activation via TRAF2 | ER biogenesis, ERAD, apoptosis |

| PERK | Oligomerization, eIF2α phosphorylation | ATF4 and CHOP induction, antioxidant regulation | Translational attenuation, oxidative cell death |

| ATF6 | Golgi trafficking, proteolytic cleavage | Chaperone induction (BiP, GRP94) | Enhanced folding capacity, ER quality control |

Integrated Experimental Approaches for Studying Redox Imbalance

Methodologies for Source-Specific ROS Detection

Accurate measurement of ROS from specific cellular sources requires sophisticated experimental approaches. The following protocols represent current best practices for investigating redox imbalance in research settings:

Protocol 1: Mitochondrial Superoxide Measurement using MitoSOX Red

- Principle: MitoSOX Red reagent is a fluorogenic dye selectively targeted to mitochondria that exhibits fluorescence upon oxidation by superoxide.

- Procedure:

- Culture cells in appropriate growth medium and apply experimental treatments.

- Load cells with 2-5 μM MitoSOX Red in buffer for 15-30 minutes at 37°C.

- Wash cells with warm buffer to remove excess dye.

- Acquire fluorescence using flow cytometry (excitation/emission: 510/580 nm) or fluorescence microscopy.

- Validation: Include controls with mitochondrial inhibitors (e.g., rotenone for complex I, antimycin A for complex III) and antioxidants (e.g., Mito-TEMPO).

- Applications: Assessment of mitochondrial ROS in response to inflammatory stimuli, metabolic challenges, or pharmacological interventions [17] [18].

Protocol 2: NOX Activity Assay using Lucigenin-Enhanced Chemiluminescence

- Principle: Lucigenin undergoes redox cycling, producing light emission in the presence of superoxide anion.

- Procedure:

- Prepare membrane fractions from tissues or cells via differential centrifugation.

- Add NADPH (100 μM) as substrate to initiate the reaction.

- Measure chemiluminescence in the presence of lucigenin (5 μM) using a luminometer.

- Specificity Controls: Include inhibitors such as diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) or apocynin, and validate using cells deficient in specific NOX isoforms.

- Normalize results to protein concentration.

- Applications: Quantification of NOX activity in vascular tissues, immune cells, and disease models [19].

Protocol 3: ER Stress and ROS Detection using ER-Targeted HyPer Sensor

- Principle: The HyPer sensor is a genetically encoded fluorescent probe sensitive to Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ that can be targeted to the ER lumen.

- Procedure:

- Transfect cells with ER-HyPer plasmid using appropriate transfection methods.

- After 24-48 hours, treat cells with ER stress inducers (e.g., tunicamycin, thapsigargin).

- Measure fluorescence ratio (excitation: 420 nm/500 nm, emission: 516 nm) using fluorescence microscopy or plate readers.

- Parallel Assessment: Combine with UPR reporter assays (e.g., XBP1 splicing, CHOP expression) to correlate ER stress with redox changes.

- Applications: Investigation of ER redox dynamics during protein misfolding, nutrient stress, and inflammatory signaling [21] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Cellular Redox Imbalance

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Target/Function | Research Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MitoTEMPO | Mitochondrial superoxide | Scavenges mitochondrial O₂•⻠| Cell-permeable, mitochondrial-targeted |

| Apocynin | NOX2 assembly inhibitor | Suppresses NOX2-derived ROS | Requires metabolic activation; specificity limitations |

| 4-PBA | Chemical chaperone | Attenuates ER stress | May affect multiple folding pathways |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondrial superoxide | Detection and quantification | Specificity requires validation with inhibitors |

| DHE (Dihydroethidium) | Cellular superoxide | Histochemical detection | Oxidized products intercalate with DNA |

| Lucigenin | Superoxide anion | Chemiluminescence-based NOX activity assay | Redox cycling may artifactually increase signal |

| ER-Tracker dyes | Endoplasmic reticulum | Live-cell ER labeling | Compatible with other fluorescent probes |

| HyPer sensors | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Genetically encoded redox sensing | Ratiometric measurement enables quantification |

| 1,2-Dioleoyl-Sn-Glycerol | 1,2-Dioleoyl-Sn-Glycerol, CAS:24529-88-2, MF:C39H72O5, MW:621.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| N-Isobutyryl-D-cysteine | N-Isobutyryl-D-cysteine, CAS:124529-07-3, MF:C7H13NO3S, MW:191.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Investigating Cellular Redox Imbalance

The intricate interplay between mitochondrial, NOX-derived, and ER-generated ROS creates a complex redox signaling network that profoundly influences inflammatory responses and disease pathogenesis [4] [22]. Rather than functioning in isolation, these cellular compartments engage in cross-talk that amplifies redox imbalances under pathological conditions [21] [18] [22]. Future research directions should focus on developing more precise tools for real-time monitoring of compartment-specific ROS, elucidating the spatiotemporal dynamics of redox signaling, and identifying source-specific inhibitors with therapeutic potential. The integration of redox proteomics, genetically encoded biosensors, and systems biology approaches will provide unprecedented insights into how coordinated redox regulation from these diverse cellular sources orchestrates both physiological signaling and pathological inflammation in human disease.

The cellular response to oxidative stress is orchestrated by a complex network of redox-sensitive signaling pathways. Key nodes within this network—NF-κB, MAPK, Nrf2, and the NLRP3 inflammasome—integrate oxidative cues to direct critical cellular decisions regarding inflammation, survival, and programmed cell death. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the molecular architecture, activation mechanisms, and intricate crosstalk between these pathways. Framed within the context of inflammation and disease pathogenesis, this review synthesizes current mechanistic understanding and presents structured experimental data, detailed methodologies, and essential research tools to aid investigators in navigating this dynamic field. The overarching thesis posits that a systems-level understanding of this redox-sensitive signaling interactome is fundamental to developing novel therapeutics for chronic inflammatory, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Redox signaling acts as a critical mediator in the dynamic interactions between organisms and their external environment, profoundly influencing both the onset and progression of various diseases [1]. Under physiological conditions, a delicate balance exists between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activity of antioxidant systems, a state known as redox homeostasis [1]. ROS, including superoxide (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), are now recognized not merely as toxic byproducts but as crucial signaling molecules that maintain physiological functions—a process termed redox biology [23] [24].

The principle of hormesis governs the cellular response to ROS; low levels activate signaling pathways to initiate biological processes, while high levels cause damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids, leading to oxidative stress and pathology [24]. A critical mechanism of redox signaling involves the oxidation of cysteine residues within proteins. Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ can oxidize the thiolate anion (Cys-Sâ») to sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH), causing allosteric changes that alter protein function. This modification is reversible via disulfide reductases like thioredoxin (Trx) and glutaredoxin (Grx), making it a potent signal transduction mechanism [24].

Disruption of redox homeostasis is a hallmark of numerous chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disorders, neurodegeneration, diabetes, and cancer [25] [4]. This imbalance can manifest as either oxidative stress (OS), characterized by an overabundance of ROS, or its less-appreciated counterpart, reductive stress (RS), marked by an excess of reducing equivalents like NADH, NADPH, and reduced glutathione (GSH) [4]. Both extremes disrupt redox-sensitive signaling and contribute to inflammatory pathogenesis. This review dissects the core redox-sensitive signaling nodes—NF-κB, MAPK, Nrf2, and the NLRP3 inflammasome—that translate oxidative cues into inflammatory responses, providing a mechanistic framework for understanding disease progression and identifying therapeutic opportunities.

Molecular Mechanisms of Redox-Sensitive Signaling Nodes

The NF-κB Pathway

NF-κB is a master regulator of inflammation and a key redox-sensitive transcription factor. The NF-κB family comprises five members: p50, p52, RelA (p65), c-Rel, and RelB, which form various homo- and heterodimers [26]. The most common dimer, p65-p50, is sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB proteins in unstimulated cells.

- Activation Mechanism: The canonical pathway is triggered by pro-inflammatory stimuli like TNF-α or IL-1. This leads to the activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, consisting of IKKα, IKKβ, and the regulatory subunit NEMO (IKKγ) [26]. IKK phosphorylates IκBα, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This liberates the p65-p50 dimer, allowing its nuclear translocation and binding to κB motifs in the promoter regions of target genes, leading to the expression of cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), chemokines, adhesion molecules, and enzymes like COX-2 and iNOS [4] [26].

- Redox Regulation: ROS are potent activators of NF-κB. The IKK complex is redox-sensitive, and ROS can inhibit MAPK phosphatases by oxidizing their catalytic cysteine residues, indirectly prolonging kinase signaling that feeds into NF-κB activation [4]. Furthermore, the activity of other kinases upstream of IKK, such as AKT, can be modulated by ROS.

Table 1: Key Components of the NF-κB Signaling Pathway

| Component | Function | Redox Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| IKK Complex (IKKα/IKKβ/NEMO) | Phosphorylates IκB, leading to its degradation | Activation is enhanced by ROS |

| IκBα | Inhibitory protein that sequesters NF-κB in cytosol | Target for degradation upon pathway activation |

| p65 (RelA) | Transcription factor subunit with transactivation domain | DNA binding can be modulated by redox state |

| p50 | Transcription factor subunit for DNA binding | Forms the DNA-binding core of the heterodimer |

| NEMO (IKKγ) | Regulatory subunit essential for canonical signaling | Scaffold protein; crucial for complex assembly |

The MAPK Pathway

The Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) pathways are a family of serine/threonine kinases that transduce extracellular signals into intracellular responses. Key branches include ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK.

- Activation Mechanism: MAPKs are activated through a three-tiered kinase cascade: MAPK Kinase Kinases (MAP3Ks) phosphorylate and activate MAPK Kinases (MAP2Ks), which in turn phosphorylate the MAPKs on threonine and tyrosine residues. Activated MAPKs then phosphorylate a wide range of substrates, including transcription factors, other kinases, and cytoskeletal proteins [4].

- Redox Regulation: MAPKs are major effectors of oxidative stress. ROS directly inhibit MAPK phosphatases (MKPs) by oxidizing a critical catalytic cysteine residue, leading to sustained MAPK activation [4]. The p38 and JNK pathways are particularly responsive to stress stimuli, including oxidative stress, and play significant roles in regulating apoptosis, cytokine production, and differentiation.

The Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway

The transcription factor Nrf2 (Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) is the master regulator of the cellular antioxidant response, coordinating the expression of over 250 cytoprotective genes [26] [27].

- Canonical Regulation by Keap1: Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is continuously ubiquitinated and targeted for proteasomal degradation by its negative regulator, Keap1, which acts as a substrate adaptor for a Cullin 3 (Cul3)-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [26] [27]. Keap1 is a highly redox-sensitive sensor protein containing multiple critical cysteine residues.

- Activation Mechanism: Upon exposure to oxidative stress or electrophiles, specific cysteine residues in Keap1 are modified. This causes a conformational change that inactivates the E3 ligase complex, allowing newly synthesized Nrf2 to accumulate and translocate to the nucleus [26] [27]. In the nucleus, Nrf2 forms a heterodimer with a small Maf protein and binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) in the promoter regions of its target genes.

- Non-Canonical Activation: Nrf2 can also be activated independently of Keap1 cysteine modification. The autophagy adapter protein p62/SQSTM1 can compete with Nrf2 for binding to Keap1, sequestering Keap1 into aggregates and facilitating Nrf2 stabilization [26] [27].

Table 2: Key Components of the Nrf2-Keap1 Signaling Pathway

| Component | Function | Redox Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Nrf2 | Master regulator transcription factor for antioxidant genes | Stabilized upon oxidative stress |

| Keap1 | Cysteine-rich sensor protein; negative regulator of Nrf2 | Directly modified by ROS/electrophiles |

| Cul3/Rbx1 | E3 ubiquitin ligase complex for Nrf2 ubiquitination | Constitutively active in complex with Keap1 |

| ARE | DNA promoter element (5'-TGACnnnGC-3') | Binding site for Nrf2-Maf heterodimer |

| Target Genes | HO-1, NQO1, GCLC, GPX, TXNRD1 |

Execute antioxidant and detoxification functions |

The NLRP3 Inflammasome

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that serves as a central platform for the activation of caspase-1 and the maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18, as well as the induction of a lytic form of cell death called pyroptosis [27] [28].

- Structure and Activation: The complex consists of a sensor (NLRP3), an adaptor (ASC), and an effector (caspase-1) [28]. Its activation typically requires a two-step process: a priming signal (e.g., through TLR4-NF-κB) upregulates the expression of NLRP3 and pro-IL-1β, and an activation signal triggers complex assembly.

- Redox Regulation: ROS are a well-established trigger for NLRP3 activation [27] [28]. Multiple sources of ROS, including mitochondrial ROS, NOX-derived ROS, and ER stress-induced ROS, can promote inflammasome assembly. The specific molecular mechanism by which ROS activates NLRP3 is still under investigation but may involve direct oxidation of NLRP3 or associated proteins, or indirect effects via the oxidation of cellular components like mitochondrial DNA or cardiolipin, which can then be released as DAMPs.

Pathway Crosstalk: An Integrated Redox Signaling Network

The redox-sensitive pathways do not operate in isolation but form a dense, interconnected network characterized by extensive crosstalk, which can be either antagonistic or synergistic.

The Antagonistic Nrf2-NF-κB Crosstalk

A prime example of pathway crosstalk is the predominantly antagonistic relationship between Nrf2 and NF-κB [26] [29]. This occurs at multiple levels:

- Competition for Transcriptional Coactivators: Both Nrf2 and NF-κB require the coactivator CBP (CREB-binding protein) for efficient gene transcription. They compete for binding to limited pools of CBP, such that activation of one pathway can sequester CBP and suppress the other [29].

- Direct Transcriptional Regulation: Nrf2 can directly suppress the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and IL-1β, thereby dampening the NF-κB-driven inflammatory response [27].

- Redox-Mediated Inhibition: By enhancing the expression of antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes, Nrf2 reduces intracellular ROS levels, which can diminish ROS-dependent activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways [4] [26].

This reciprocal inhibition suggests that the cellular response to stress is channeled towards either a pro-survival, antioxidant program (Nrf2) or a pro-inflammatory, immune-activating program (NF-κB).

Nrf2 and the Inflammasome

Nrf2-activating compounds have been shown to inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation and subsequent inflammation [27]. The mechanisms are multifaceted and may involve:

- Reduction of ROS: As a primary activator of NLRP3, reducing cellular ROS via Nrf2 is a key inhibitory mechanism.

- Upregulation of Heme Oxygenase-1 (HO-1): The Nrf2 target gene HO-1 has potent anti-inflammatory effects, including the generation of carbon monoxide and bilirubin, which can suppress inflammasome activity.

- Modulation of Autophagy: Nrf2 can influence autophagic flux, which is crucial for clearing damaged mitochondria (a source of NLRP3-activating DAMPs) and potentially degrading inflammasome components.

MAPK as a Common Integrator

The MAPK pathways, particularly p38 and JNK, are activated by a wide array of stimuli, including ROS and inflammatory cytokines. They serve as integrators that can feed into both NF-κB and NLRP3 activation. For instance, MAPK signaling can enhance NF-κB transcriptional activity and is involved in the priming step of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by upregulating NLRP3 expression [4].

The following diagram illustrates the core crosstalk and regulatory relationships between these key pathways:

Experimental Analysis of Redox Signaling

Studying redox-sensitive pathways requires a combination of molecular biology, biochemical, and cell imaging techniques to assess pathway activation, protein modifications, and functional outcomes.

Key Methodologies

1. Assessing Nrf2 Pathway Activation

- Western Blotting: Measure protein levels of Nrf2 in nuclear vs. cytoplasmic fractions. Assess Keap1 degradation and levels of key target proteins (e.g., NQO1, HO-1).

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR): Quantify mRNA levels of Nrf2 target genes (e.g.,

NQO1,HMOX1,GCLM). A significant upregulation indicates pathway activation. - ARE-Luciferase Reporter Assay: Cells are transfected with a plasmid containing an ARE promoter sequence driving luciferase expression. Increased luminescence upon treatment indicates Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activation.

- Immunofluorescence: Visualize the translocation of Nrf2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus using specific antibodies.

2. Detecting NF-κB and MAPK Activation

- Phospho-Specific Western Blotting: The gold standard. Use antibodies against:

- NF-κB pathway: Phospho-IκBα (Ser32/36), Phospho-IKKα/β (Ser176/180), Phospho-p65 (Ser536).

- MAPK pathway: Phospho-p44/42 (Thr202/Tyr204) for ERK, Phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185), Phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182).

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA): To assess NF-κB DNA-binding activity in nuclear extracts (less common now due to advanced Western blotting).

- ELISA-based Transcription Factor Activity Assays: Commercial kits are available to quantify the DNA-binding activity of NF-κB or Nrf2 from nuclear extracts.

3. Measuring NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

- Caspase-1 Activity Assay: Use fluorogenic substrates (e.g., YVAD-AFC) to measure caspase-1 enzymatic activity in cell lysates.

- Western Blotting for IL-1β and IL-18: Detect the cleaved, mature forms (p17 for IL-1β) in cell culture supernatants. Also, assess pro-IL-1β levels in lysates (priming readout).

- ASC Speck Formation Assay: Use immunofluorescence microscopy to visualize the large, micron-sized ASC oligomers that form upon inflammasome assembly.

4. Monitoring Redox State

- ROS-Sensitive Dyes: Cell-permeable fluorogenic probes like Hâ‚‚DCFDA (for general ROS), MitoSOX Red (for mitochondrial superoxide), and DHE (for superoxide).

- GSH/GSSG Ratio: Measured using enzymatic recycling assays or HPLC to quantify the cellular reduced-to-oxidized glutathione ratio, a key indicator of redox balance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Studying Redox-Sensitive Pathways

| Reagent / Assay | Function / Target | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sulforaphane | Natural isothiocyanate; canonical Nrf2 activator via Keap1 cysteine modification | Positive control for Nrf2 pathway induction; studying antioxidant responses [27]. |

| tert-Butylhydroquinone (tBHQ) | Synthetic phenolic antioxidant; potent Nrf2 inducer | Used in vitro to activate Nrf2 and study ARE-driven gene expression. |

| ML385 | Small molecule inhibitor that blocks Nrf2 binding to ARE | Validating the dependency of an observed effect on Nrf2 transcriptional activity. |

| TNF-α | Pro-inflammatory cytokine; potent activator of NF-κB canonical pathway | Standard stimulus for inducing NF-κB-dependent inflammation in cellular models. |

| Bay 11-7082 | Inhibitor of IκBα phosphorylation | Confirming NF-κB involvement in a signaling process. |

| LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) | TLR4 agonist; provides priming signal for NLRP3 inflammasome | Used in combination with a second signal (e.g., ATP, nigericin) to activate NLRP3 [28]. |

| MCC950 | Potent and selective small molecule inhibitor of NLRP3 | Determining the specific role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in a pathological model [28]. |

| Hâ‚‚DCFDA | Cell-permeable dye, fluoresces upon oxidation by broad-spectrum ROS | General measurement of intracellular oxidative stress. |

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondria-targeted dye sensitive to superoxide | Specific detection of mitochondrial ROS, a key activator of NLRP3. |

| ARE-Luciferase Reporter | Plasmid for monitoring Nrf2 transcriptional activity | High-throughput screening for Nrf2 activators/inhibitors. |

| 3,7-Dimethyluric Acid | 3,7-Dimethyluric Acid, CAS:13087-49-5, MF:C7H8N4O3, MW:196.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,6-Dibromopyridazine | 3,6-Dibromopyridazine, CAS:17973-86-3, MF:C4H2Br2N2, MW:237.88 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental workflow below outlines a typical strategy for dissecting the role of these pathways in a cellular model of oxidative stress and inflammation:

The redox-sensitive signaling nodes NF-κB, MAPK, Nrf2, and the NLRP3 inflammasome form an intricate regulatory network that dictates cellular fate in response to oxidative challenge. The antagonistic relationship between the pro-survival Nrf2 pathway and the pro-inflammatory NF-κB and NLRP3 pathways suggests a cellular "switch" that determines the balance between cytoprotection and inflammation. Dysregulation of this balance is a cornerstone of pathogenesis in a wide array of chronic diseases.

Future research will benefit from a more dynamic and quantitative approach. Single-cell analysis techniques will reveal heterogeneity in pathway activation within cell populations. Advanced redox proteomics will allow for the systematic identification of specific cysteine residues modified under different stress conditions, providing a more precise map of the redox signaling network. Furthermore, the emerging concept of reductive stress and its impact on inflammation warrants deeper investigation [4].

From a therapeutic perspective, the crosstalk between these pathways offers both challenges and opportunities. While broad-spectrum antioxidants have shown limited clinical success, targeting specific nodes of the redox network holds greater promise. For example, the development of specific Nrf2 activators or KEAP1 inhibitors is a vibrant area of research for combating diseases driven by oxidative stress. Conversely, inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome with specific agents like MCC950 is being explored for inflammatory diseases [28]. A nuanced, systems-level understanding of this redox interactome will be essential for designing next-generation therapeutics that can precisely modulate the inflammatory response in a myriad of human diseases.

Redox signaling, the process by which reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other redox-active molecules modulate cellular functions, serves as a fundamental regulatory mechanism in inflammation and immunity [30]. This whitepaper examines how redox pathways precisely control key immune processes, particularly macrophage polarization and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation (NETosis), alongside cytokine production, within the broader context of inflammatory diseases and therapeutic development. The bidirectional nature of redox signaling is critical to its function, with physiological levels of ROS acting as signaling messengers while excessive or sustained production leads to oxidative stress and pathological inflammation [4] [31] [3]. A sophisticated antioxidant system, including the NRF2 pathway, maintains this delicate balance [1]. Understanding these mechanisms provides crucial insights for developing targeted therapies for conditions ranging from cardiovascular and metabolic diseases to cancer and autoimmune disorders [1] [32] [3].

Redox Regulation of Macrophage Polarization and Function

Molecular Mechanisms of Redox Signaling in Macrophages

Macrophages exhibit remarkable functional plasticity, dynamically shifting their polarization state in response to microenvironmental cues. Redox signaling plays a pivotal role in directing these phenotypic changes through several molecular mechanisms:

Redox-Sensitive Transcription Factors: NF-κB represents the most well-characterized redox-dependent pathway in macrophages [4] [31]. ROS promote the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB proteins, enabling NF-κB nuclear translocation and transcription of pro-inflammatory genes including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [4]. The NRF2-Keap1 system functions as a complementary protective axis, where ROS modify specific cysteine residues on Keap1, leading to NRF2 stabilization and nuclear translocation to induce antioxidant gene expression [4] [1]. The HIF-1α pathway is additionally activated under hypoxic conditions, driving expression of glycolytic enzymes and pro-inflammatory mediators [31].

Cysteine Oxidation in Signaling Proteins: Redox signaling primarily operates through the reversible oxidation of cysteine thiols (-SH) to sulfenic acid (-SOH) in target proteins [33] [30]. This modification significantly alters protein structure, activity, and localization. Key signaling nodes affected include protein kinases (PKA, PKC, CaMKII), receptor tyrosine kinases, and phosphatases [31] [30]. The specificity of these modifications is governed by kinetic parameters and subcellular localization, ensuring precise signal transduction [33].

Metabolic Reprogramming: Distinct macrophage polarization states exhibit characteristic metabolic profiles. M1 macrophages primarily utilize glycolysis, while M2 macrophages rely more on oxidative phosphorylation [31] [34]. Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) generated from complexes I and III of the electron transport chain activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote IL-1β and IL-18 secretion [4] [31]. NOX-derived ROS additionally influence metabolic enzyme activity, creating feedback loops that sustain polarization states [31].

Table 1: Primary ROS Sources in Macrophage Polarization and Signaling

| ROS Source | Subcellular Location | Primary ROS | Role in Macrophage Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOX2 | Plasma membrane, phagosomal membrane | O₂•â», Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Microbial killing, pro-inflammatory polarization, cytokine production |

| Mitochondrial ETC | Mitochondrial matrix, inner membrane | O₂•â», Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Inflammasome activation, HIF-1α stabilization, metabolic reprogramming |

| NOX4 | Various intracellular membranes | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Host defense against specific pathogens, cell death in response to oxLDL |

| p66Shc | Mitochondrial intermembrane space | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ | Pro-apoptotic signaling, mitochondrial dysfunction |

Experimental Approaches for Studying Redox Signaling in Macrophages

Investigating redox mechanisms in macrophage biology requires specialized methodologies that capture the dynamic and compartmentalized nature of these processes:

Genetically Encoded Redox Probes: Modern approaches employ fluorescent protein-based probes (e.g., roGFP, HyPer) targeted to specific subcellular compartments (mitochondria, cytosol, phagosomal space) [30]. These tools enable real-time, compartment-specific measurements of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and glutathione redox potential in live cells with high spatiotemporal resolution [30]. For example, HyPer targeted to the mitochondrial matrix can reveal mtROS bursts following TLR4 activation.

Pharmacological Modulation of ROS Pathways: Specific inhibitors and activators help delineate contributions from distinct ROS sources:

- NOX inhibition: Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) and apocynin (though with specificity limitations)

- Mitochondrial ROS scavenging: MitoTEMPO (mitochondria-targeted antioxidant)

- Xanthine oxidase inhibition: Allopurinol

- NRF2 pathway activation: Sulforaphane

Gene Silencing and Knockout Models: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout or siRNA knockdown of specific ROS-generating enzymes (NOX isoforms, mitochondrial complexes) or antioxidant proteins (NRF2, SOD, GPX) enables determination of their specific contributions to macrophage polarization and function [34].

Redox Control of Neutrophil NETosis

Molecular Pathways of NET Formation

Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are web-like structures composed of decondensed chromatin decorated with antimicrobial proteins that neutrophils expel to immobilize and neutralize pathogens [32]. Redox signaling plays a fundamental role in regulating multiple NETosis pathways:

NADPH Oxidase-Dependent NETosis: The classical pathway of NET formation requires assembly and activation of NOX2 at the plasma membrane, generating superoxide that is dismutated to Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ [31] [32]. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) then utilizes Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to produce hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a potent oxidant that activates neutrophil elastase and MPO itself [31] [32]. These proteases translocate to the nucleus, where they degrade histones and promote chromatin decondensation, a prerequisite for NET release [32].

NADPH Oxidase-Independent Pathways: Certain stimuli, including calcium ionophores and uric acid crystals, can trigger NETosis through mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) production rather than NOX2 activation [32]. In this pathway, mtROS directly promote chromatin decondensation and NET release, demonstrating the versatility of redox signaling in regulating this process [32].

Redox Regulation of Cell Death Mechanisms: NETosis intersects with various cell death pathways. The interplay between ROS and the kinases RIPK1 and RIPK3 can promote necroptosis, which in neutrophils can be associated with NET release [32]. Additionally, metabolic reprogramming toward glycolysis provides both energy and biosynthetic precursors necessary for NET formation, with several glycolytic enzymes physically associating with NOX2 to potentially facilitate its activation [31].

Table 2: Redox-Dependent Mediators of NETosis and Their Functions

| Mediator | Source/Type | Role in NETosis | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| NOX2 | Enzyme complex | Generates O₂•â»/Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ for MPO activation and downstream signaling | Required for classical NETosis; assembles with cytoskeletal elements |

| Myeloperoxidase (MPO) | Heme enzyme | Produces HOCl from Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚; processes and activates proteases | Activates neutrophil elastase; synergizes with NE in histone degradation |

| Mitochondrial ROS | Mitochondrial ETC | Promotes chromatin decondensation in NOX-independent NETosis | Alternative pathway when NOX2 is deficient or inhibited |

| Neutrophil Elastase (NE) | Serine protease | Cleaves histones and nuclear proteins to decondense chromatin | Activated by MPO-generated oxidants; translocates to nucleus |

| PAD4 | Enzyme | Citrullinates histones to reduce DNA-histone binding | Can be activated by redox conditions; promotes chromatin decondensation |

Methodologies for NETosis Research