Redox Homeodynamics vs. Homeostasis: A Paradigm Shift for Precision Medicine and Drug Discovery

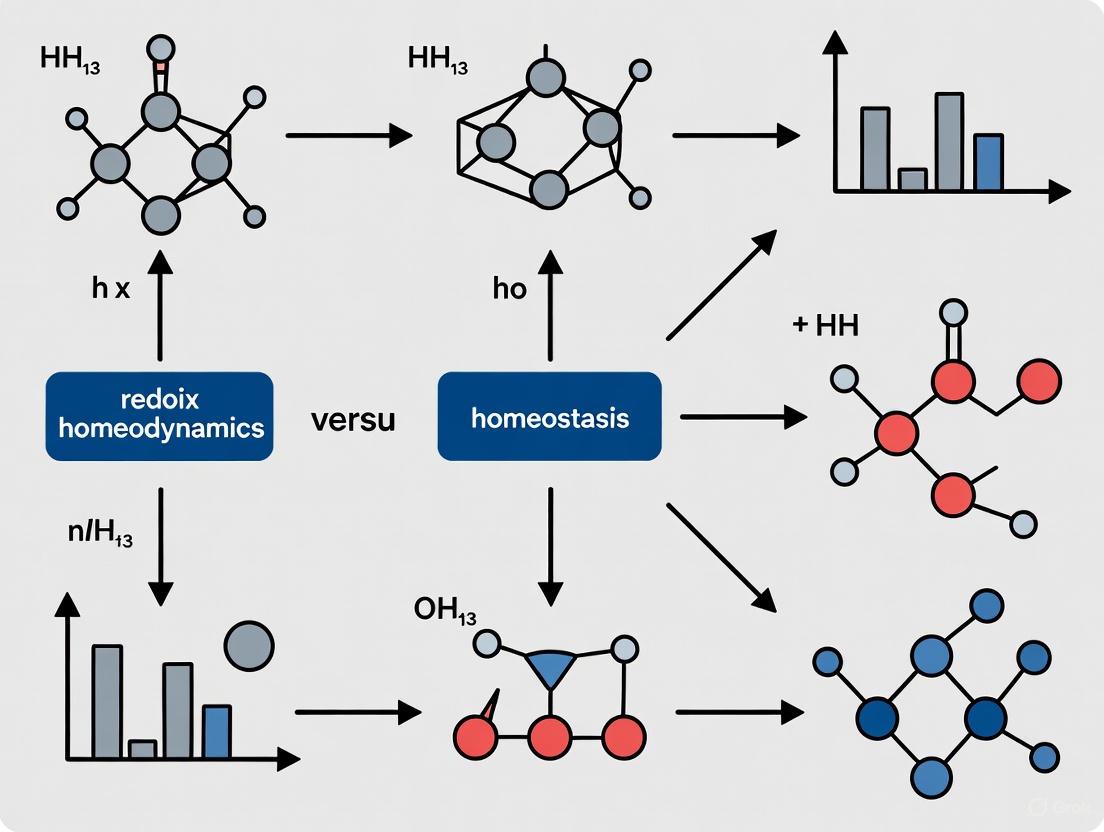

This article explores the critical paradigm shift from the static concept of redox homeostasis to the dynamic model of redox homeodynamics.

Redox Homeodynamics vs. Homeostasis: A Paradigm Shift for Precision Medicine and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the critical paradigm shift from the static concept of redox homeostasis to the dynamic model of redox homeodynamics. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it delves into the foundational principles of this continuous, adaptive process and its disruption in disease states. The content covers advanced methodologies for quantifying redox states, analyzes the pitfalls of broad-spectrum antioxidants, and proposes strategies for targeted therapeutic intervention. Finally, it validates the homeodynamics framework through its application in precision medicine, offering a comparative analysis of its advantages over the traditional homeostasis model for developing novel, context-specific treatments for cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases.

From Static Balance to Dynamic Control: Deconstructing Redox Homeodynamics

Within redox biology, a paradigm shift is occurring from a classical view of static maintenance of balance toward a modern understanding of continuous adaptation. This whitepaper delineates the conceptual and operational distinctions between redox homeostasis, defined as the dynamic equilibrium maintaining reducing and oxidizing (redox) reactions within a narrow, optimal range, and redox homeodynamics, which describes the continuous adaptive process that transiently expands or contracts the homeostatic range in response to sub-toxic signaling events. For researchers and drug development professionals, appreciating this distinction is critical for designing targeted therapeutic strategies that either maintain equilibrium or harness adaptive responses.

The concept of homeostasis, originating from Claude Bernard's "milieu intérieur" and later coined by Walter Cannon, has long been a cornerstone of physiology, describing the maintenance of nearly constant internal conditions [1] [2]. In the context of redox biology, redox homeostasis has been traditionally understood as the dynamic balance between pro-oxidants (electrophiles) and antioxidants (nucleophiles) within the cell [3] [4]. This balance is crucial for normal cellular function, as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) are not merely harmful byproducts but also essential signaling molecules [5] [4].

However, emerging research underscores that biological systems do not merely defend a fixed setpoint. Instead, they demonstrate homeodynamics—a continuous adaptive capacity that allows for transient changes in the homeostatic range itself. This adaptive process, sometimes termed Adaptive Homeostasis, enables organisms to adjust their functional stability in response to mild, non-damaging stimuli, such as dietary components, exercise, or low levels of chemical agents [2]. This whitepaper explores the technical definitions, mechanisms, and experimental distinctions between these two interconnected concepts, providing a framework for their application in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Redox Homeostasis: A Dynamic Equilibrium

Core Definition and Characteristics

Redox Homeostasis is the dynamic equilibrium process that maintains the balance between reducing and oxidizing reactions within a cell, preserving the optimum redox steady state [5] [4]. It is a highly responsive system that continuously senses and realigns metabolic activities to restore redox balance following perturbations. The key characteristics of the redox homeostasis model are:

- Dynamic Equilibrium: The system maintains a "nucleophilic tone" through continuous feedback mechanisms, not a static, fixed state [3] [4].

- Narrow Optimal Range: The goal of the system is to confine redox potentials to a strict, favorable range for cellular function [1].

- Reactive Restoration: The system operates primarily through feedback loops that react to changes and disturbances, forcing the variable back into its normal range [1].

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The maintenance of redox homeostasis involves a complex network of enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), such as superoxide radical (●O2⁻) and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), are generated as byproducts of metabolism and by dedicated enzymes like NADPH oxidases [5]. At controlled levels, these molecules act as crucial secondary messengers in redox signaling.

A central regulator is the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway, the master regulator of the cellular antioxidant response [3] [5] [4]. Under basal conditions, the cytosolic protein Keap1 targets the transcription factor Nrf2 for proteasomal degradation. Upon an increase in oxidative or electrophilic stress, this degradation is halted, allowing Nrf2 to translocate to the nucleus, dimerize with small Maf proteins, and bind to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), activating the transcription of a battery of cytoprotective genes. These genes include NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and enzymes involved in glutathione synthesis [5] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the core Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway that maintains redox homeostasis:

Redox Signaling Mechanisms: Redox signaling occurs largely through reversible redox post-translational modifications (rPTMs) of specific cysteine thiolates (-SH) in target proteins [5] [4]. Oxidation by H₂O₂ can form sulfenic acid (-SOH), which can lead to disulfide bond (-S-S-) formation. These modifications are readily reversed by disulfide reductase enzymes like thioredoxin (Trx) and glutaredoxin (Grx), ensuring the transient nature of the signal. This reversible oxidation can regulate the activity of key signaling proteins, such as inhibiting Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases (PTPs), thereby potentiating kinase signaling [5].

Redox Homeodynamics: A Continuous Adaptive Process

Core Definition and Characteristics

Redox Homeodynamics (or Adaptive Homeostasis) is the transient expansion or contraction of the homeostatic range in response to exposure to sub-toxic, non-damaging, signaling molecules or events, or the removal of such molecules or events [2]. This concept moves beyond maintaining a fixed range to encompass the biological capacity for adaptation. Its key characteristics are:

- Adaptive Capacity: The system's setpoint or range of "normal" capacity can be adjusted based on environmental cues or previous exposures [2].

- Transient Nature: The expansion or contraction of the homeostatic range is not permanent but is calibrated to the duration and intensity of the stimulus.

- Anticipatory Potential: Unlike classic reactive homeostasis, homeodynamics can involve feedforward mechanisms that pre-emptively adjust system capacity in anticipation of a challenge [1] [2].

This concept is distinct from related terms like allostasis (maintaining stability through change) and hormesis (a biphasic dose response to toxins), though there is some conceptual overlap. Adaptive homeostasis specifically refers to responses to mild, non-damaging stimuli and involves changes to the normal capacity of systems [2].

Molecular Basis of Adaptation

The mechanisms underlying redox homeodynamics often involve the same molecular players as homeostasis, such as the Nrf2 pathway, but their activity is modulated to reset the system's operational range. For instance, a mild electrophilic stress might not only activate Nrf2 to restore the immediate redox balance but also prime the system for a subsequent challenge by maintaining a slightly elevated level of antioxidant enzymes, thereby transiently expanding the homeostatic range [3] [2].

The following diagram contrasts the classical homeostatic response with the adaptive homeodynamic response:

Para-hormesis: This is a key concept in homeodynamics, where certain natural dietary compounds (phytochemicals) can activate stress-response pathways like Nrf2 without causing significant damage, thereby mimicking the effect of endogenously produced electrophiles and contributing to long-term health by favoring the maintenance of an adapted homeostatic state [3] [4].

Experimental Distinction: Methodologies and Assessment

Distinguishing between homeostasis and homeodynamics in a research setting requires carefully designed experiments that measure not only the immediate response to a stressor but also the kinetics of recovery and the subsequent capacity of the system to handle a second challenge.

Quantitative Assessment of Redox States

A variety of techniques are employed to quantify the redox state of cells and tissues, providing data to differentiate static imbalance from dynamic adaptation.

Table 1: Key Analytical Methods for Assessing Redox Homeostasis and Homeodynamics

| Method | Measured Parameter | Technical Insight | Application in Concept Discrimination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redox-Sensitive GFP (roGFP) | Dynamic, real-time changes in glutathione redox potential (EGSSG/2GSH) [5]. | Genetically encoded sensor allowing compartment-specific monitoring in live cells. | Tracks real-time recovery kinetics after a perturbation; slower recovery suggests impaired homeostasis. |

| LC-MS/MS for Oxidized Lipids | Levels of specific lipid peroxidation products (e.g., 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE), malondialdehyde (MDA)) [6] [4]. | Provides a sensitive and specific measure of oxidative damage to membranes. | High sustained levels indicate failed homeostasis; a primed system in homeodynamics may show a blunted response to a second, similar challenge. |

| Western Blot for rPTMs | Detection of specific redox post-translational modifications (e.g., cysteine sulfenylation, nitrosylation) [5] [4]. | Uses specific antibodies to detect modified proteins; can assess signaling activity. | Identifies activation of specific pathways (e.g., Nrf2) and their return to baseline, differentiating transient signaling (homeodynamics) from chronic activation (stress). |

| qPCR/Western for Nrf2 Target Genes | mRNA or protein levels of HO-1, NQO1, GSTs, etc. [5] [4]. | Measures the transcriptional output of a key redox regulatory pathway. | A transient increase indicates successful adaptation (homeodynamics), while a persistent elevation may indicate chronic oxidative stress overwhelming homeostasis. |

Protocol for Differentiating Homeostasis from Homeodynamics

The following experimental workflow is designed to probe the adaptive capacity of a biological system, thereby distinguishing a homeodynamic response.

Protocol Title: Sequential Challenge Assay to Quantify Adaptive Redox Homeodynamics.

Objective: To determine if a mild, sub-toxic preconditioning stimulus expands the homeostatic range and confers enhanced protection against a subsequent toxic challenge.

Cell Culture & Preconditioning:

- Use a relevant cell line (e.g., primary hepatocytes, neuronal cells).

- Test Group: Treat with a mild, sub-toxic dose of a redox-active compound (e.g., 10-50 µM sulforaphane, a known Nrf2 inducer) for 6-12 hours.

- Control Group: Treat with vehicle only (e.g., DMSO < 0.1%).

- Washout: Remove the medium, wash cells with PBS, and add fresh compound-free medium for a 6-24 hour "recovery" period. This step is crucial for observing adaptation beyond the immediate stress response.

Toxic Challenge:

- Expose both Preconditioned and Control cells to a standardized oxidative insult (e.g., 200-500 µM H₂O₂ or 50-100 µM tert-butyl hydroperoxide (tBHP)) for a defined period (e.g., 2-6 hours).

Endpoint Analysis (Post-Challenge):

- Cell Viability: Measure using MTT or Calcein-AM assay. A significantly higher viability in the Preconditioned group indicates successful adaptation.

- Redox Status: Quantify using roGFP imaging or by measuring the GSH/GSSG ratio via enzymatic recycling assays. A more reduced state in Preconditioned cells suggests an enhanced antioxidant capacity.

- Molecular Markers: Analyze by qPCR/Western blot for Nrf2 target genes (HO-1, NQO1). The Preconditioned group may show a more rapid or robust induction of these genes upon challenge.

Interpretation: A system operating only with classical homeostasis will return to its original baseline after the preconditioning washout and will be equally susceptible to the toxic challenge as the control. A system demonstrating homeodynamics will retain a "memory" of the preconditioning, evident as an expanded homeostatic range that provides greater resilience to the subsequent challenge.

The following diagram outlines this experimental workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Redox Homeostasis and Homeodynamics Research

| Reagent / Assay Kit | Primary Function | Application in Redox Research |

|---|---|---|

| CellROX / MitoSOX Probes | Fluorescent detection of general cellular and mitochondrial superoxide, respectively. | Qualitative/quantitative assessment of ROS production during stress and adaptation. |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio Detection Kit | Enzymatic quantification of reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) glutathione. | A cornerstone assay for defining the central redox couple and overall cellular redox state. |

| roGFP Plasmids | Genetically encoded biosensor for real-time, compartment-specific redox monitoring. | Gold standard for dynamic, non-disruptive tracking of redox potential fluctuations. |

| Sulforaphane | Natural compound that acts as a potent Nrf2 activator by modifying Keap1 cysteine residues. | Standard tool for preconditioning experiments to induce an adaptive homeodynamic response. |

| Anti-Nrf2 & Anti-Keap1 Antibodies | Protein detection and localization via Western Blot, Immunoprecipitation, or Immunofluorescence. | Essential for monitoring the status and activity of the key Nrf2-Keap1 signaling axis. |

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) | Precursor for glutathione synthesis and a direct antioxidant/redox modulator. | Commonly used to test the necessity of redox changes in a observed phenotype or signaling event. |

| Recombinant Thioredoxin (Trx) | Key disulfide reductase enzyme that reverses oxidative protein modifications. | Used to demonstrate the reversibility of redox signaling and its functional consequences. |

The distinction between redox homeostasis and redox homeodynamics is more than semantic; it represents a fundamental shift in how researchers conceptualize the interaction between organisms and their environment. The classical model of homeostasis describes the elegant machinery that maintains stability, while the homeodynamics model explains the plasticity that confers resilience and facilitates survival in a fluctuating environment.

For drug development, this distinction is critically important. Therapeutic strategies aimed at crudely suppressing all ROS with high-dose antioxidants have largely failed in clinical trials, and in some cases, have been harmful [6] [5]. This failure can be understood through the lens of homeodynamics: such approaches likely disrupt essential redox signaling and impair the body's innate adaptive responses. The future lies in precision redox medicine, which involves:

- Modulation, Not Blunt Inhibition: Developing therapeutics that fine-tune redox signaling rather than ablating it [6].

- Context-Specific Strategies: Applying pro-oxidant therapies in contexts like cancer, where disrupting the heightened redox homeostasis of tumor cells is desirable, and using targeted Nrf2 activators for chronic degenerative diseases [6] [7].

- Temporal Control: Timing interventions to work with the body's natural adaptive rhythms, potentially using preconditioning (homeodynamic) strategies to protect against anticipated insults, such as the cardiotoxic effects of chemotherapy [6].

Ultimately, embracing the concept of redox homeodynamics will enable scientists and clinicians to develop more sophisticated and effective interventions that support the body's inherent capacity for adaptive, healthy living.

Redox signaling represents a fundamental regulatory mechanism in cellular biology, governing processes from proliferation and differentiation to programmed cell death. This whitepaper examines the core molecular players in redox signaling—reactive oxygen species (ROS), reactive nitrogen species (RNS), glutathione (GSH), thioredoxin (Trx), and NADPH systems—through the conceptual framework of redox homeodynamics rather than static homeostasis. Unlike the traditional homeostasis concept which implies a stable equilibrium, homeodynamics better reflects the dynamic, adaptive nature of redox regulation where systems maintain functional integrity through continuous flux and interaction between oxidizing and reducing species [8] [5]. This dynamic interplay enables precise spatiotemporal control of cellular signaling networks, with disruption leading to pathological conditions including neurodegenerative diseases, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer.

The concept of redox homeodynamics provides a transformative perspective on cellular redox regulation. While homeostasis suggests a return to a fixed set point, homeodynamics acknowledges that living systems maintain stability through continuous activity and adaptation to internal and external challenges [5]. This paradigm is particularly apt for redox biology, where the balance between oxidants and antioxidants is not static but rather a highly responsive, dynamic system that senses changes in redox status and realigns metabolic activities to restore functional balance.

In practical terms, redox homeodynamics involves constant surveillance and adjustment through interconnected systems including glutathione, thioredoxin, NADPH-regenerating systems, and their associated enzymes [5]. Under physiological conditions, nonradical ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) function as crucial second messengers to modulate redox signaling by orchestrating multiple redox sensors at concentrations ranging from 1-100 nM [8]. However, when redox homeodynamics is disrupted, excessive ROS accumulation—termed oxidative stress—leads to biomolecule damage and subsequent disease pathogenesis [8].

Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species: The Signaling Messengers

ROS Diversity and Characteristics

Reactive oxygen species are not a monolithic entity but rather a diverse group of molecules with distinct chemical properties, reactivities, and biological impacts [9]. The major ROS species include:

Table 1: Key Reactive Oxygen Species in Redox Signaling

| ROS Species | Chemical Formula | Production Sources | Reactivity & Characteristics | Primary Signaling Roles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide anion | O₂•⁻ | Mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes, P450 systems | Moderate reactivity; limited membrane permeability; precursor to other ROS | Limited direct signaling; mainly precursor for H₂O₂ and ONOO⁻ |

| Hydrogen peroxide | H₂O₂ | SOD conversion of O₂•⁻, NOX4, DUOX | Moderate reactivity; membrane-diffusible; specific target oxidation | Major redox messenger; oxidizes protein cysteine residues |

| Hydroxyl radical | •OH | Fenton reaction, water radiolysis | Extremely reactive; non-specific; minimal diffusion distance | Not a signaling molecule; causes oxidative damage |

| Singlet oxygen | ¹O₂ | Photosensitization reactions | Highly reactive with organic compounds | Stress signaling; programmed cell death |

The specificity of redox signaling is largely determined by the chemical properties of each ROS. H₂O₂ has emerged as a primary redox signaling mediator due to its relative stability, ability to diffuse across membranes, and selective reactivity with specific protein cysteine residues [8] [9]. In contrast, the hydroxyl radical (•OH) is extremely reactive and immediately removes electrons from any molecule in its path, making it unsuitable for specific signaling but highly destructive to cellular components [10].

Reactive Nitrogen Species

Reactive nitrogen species, particularly nitric oxide (NO•) and its derivatives, represent another crucial class of redox signaling mediators. Peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), formed from the diffusion-limited reaction between superoxide and nitric oxide, is a strong two-electron oxidant that can modify protein tyrosines to form nitrotyrosines, affecting protein function [10]. The biological activity of RNS depends on the local concentration of its precursor molecules and the specific microenvironment in which it is generated.

The Major Redox Buffering Systems

Glutathione System

Glutathione (GSH) is the most abundant non-protein thiol in cells, functioning as a primary redox buffer, antioxidant, and enzyme cofactor against oxidative stress [11]. This tripeptide (γ-glutamylcysteinylglycine) is synthesized intracellularly via two ATP-dependent reactions catalyzed by γ-glutamylcysteine ligase (GCL) and glutathione synthetase (GS).

The glutathione system maintains redox homeodynamics through several mechanisms:

- Redox Buffering: The GSH/GSSG couple maintains intracellular redox status with a ratio typically >100:1 under physiological conditions, decreasing to 10:1 or less under oxidative stress [11].

- Enzyme Cofactor: GSH serves as an essential cofactor for glutathione peroxidases (GPx) which reduce H₂O₂ and lipid hydroperoxides to water and corresponding alcohols.

- Protein Modification: GSH participates in S-glutathionylation, a reversible post-translational modification that regulates protein function and protects cysteine residues from irreversible oxidation [11].

The brain is particularly vulnerable to GSH depletion due to its high oxygen consumption, abundance of unsaturated fatty acids, and relatively low antioxidant capacity [11]. Neuronal GSH synthesis depends on cysteine uptake through excitatory amino acid carrier 1 (EAAC1), highlighting the tight coupling between redox homeostasis and neuronal function [11].

Thioredoxin System

The thioredoxin system represents another essential redox regulatory network centered on thioredoxin (Trx), a small (12 kDa) multifunctional redox-active protein [12]. The system includes:

- Thioredoxin (Trx): Contains a conserved active-site sequence (-Cys-Gly-Pro-Cys-) that undergoes reversible oxidation/reduction during disulfide reduction.

- Thioredoxin Reductase (TrxR): A NADPH-dependent flavoenzyme that reduces oxidized Trx.

- Peroxiredoxin (Prx): Thioredoxin-dependent peroxidases that reduce H₂O₂, organic hydroperoxides, and peroxynitrite.

Table 2: Thioredoxin Family Proteins and Their Cellular Roles

| Protein | Localization | Key Features | Biological Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trx-1 | Cytosol, nucleus | 12 kDa; can translocate to nucleus upon stimulation | Redox regulation, transcription factor control, apoptosis inhibition |

| Trx-2 | Mitochondria | 18.2 kDa immature protein; mitochondrial targeting sequence | Regulation of mitochondrial apoptosis, cytochrome c release inhibition |

| TRP14 | Cytosol | 14 kDa; reacts with PTEN | Cellular redox regulation, PTEN reactivation |

| Grx-1 | Cytosol, nucleus | Glutathione-dependent; dithiol or monothiol mechanisms | Reduction of protein-GSH mixed disulfides (deglutathionylation) |

The thioredoxin system collaborates with complementary antioxidant systems through overlapping functions. Glutaredoxins (Grx), which are glutathione-dependent thioredoxin family proteins, specialize in reducing protein-glutathione mixed disulfides (deglutathionylation) using glutathione as a reductant [12]. Both systems are essential for embryonic development, as demonstrated by the embryonic lethality observed in Trx-1 and Trx-2 deficient mice [12].

NADPH: The Central Reductant

NADPH serves as the central electron donor for redox homeodynamics, providing reducing equivalents for:

- Regeneration of reduced glutathione via glutathione reductase

- Reduction of thioredoxin via thioredoxin reductase

- Direct antioxidant function through NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase

- NADPH oxidase (NOX)-dependent ROS generation for signaling

The NADPH/NADP⁺ ratio is tightly regulated through the pentose phosphate pathway, malic enzyme, and NADP⁺-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase, creating direct links between cellular metabolic status and redox homeodynamics [11].

Redox Signaling Mechanisms and Molecular Targets

Cysteine Oxidation as a Central Mechanism

Redox signaling primarily occurs through specific, reversible oxidation of cysteine residues in target proteins [5]. The sulfur atom in cysteine undergoes a range of oxidative modifications that function as molecular switches:

Figure 1: Cysteine Oxidation States in Redox Signaling

The reactivity of cysteine residues toward H₂O₂ varies widely, with rate constants ranging from <1 M⁻¹s⁻¹ for non-reactive cysteines to >10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ for specialized peroxidatic cysteines in peroxiredoxins and other redox sensors. This differential reactivity provides specificity to redox signaling [5].

Recent research has revealed that per/polysulfidation of cysteine residues (formation of Cys-SSH or Cys-SnSH) may protect against irreversible oxidation during severe oxidative stress. When persulfidated cysteines are overoxidized, they form cysteine-persulfinic/sulfonic acids (Cys-S-SO₂H/SO₃H) that retain a reducible disulfide bond, allowing enzyme repair by thioredoxin or glutaredoxin systems [5].

Redox-Sensitive Signaling Pathways

Multiple major signaling pathways are regulated by redox mechanisms through reversible cysteine modifications:

Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway: The primary cellular defense against oxidative stress. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is bound by Keap1 and targeted for proteasomal degradation. Oxidative modification of specific cysteine residues in Keap1 (Cys151, Cys273, Cys288) disrupts this interaction, allowing Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus where it activates antioxidant response element (ARE)-containing genes [8] [5].

NF-κB Pathway: Redox regulation of NF-κB occurs at multiple levels, including IKK activation, IκB degradation, and NF-κB DNA binding. The pathway is differentially regulated by various ROS, with H₂O₂ often activating and higher ROS levels potentially inhibiting NF-κB signaling [13].

Other Pathways: Additional redox-sensitive pathways include HIF-1α (stabilized under hypoxia), FOXO transcription factors (activated by oxidative stress to enhance antioxidant expression), and p53 (regulated by redox modifications that affect its DNA binding and transcriptional activity) [13].

Experimental Approaches in Redox Biology

Methodological Framework

Investigating redox signaling requires careful experimental design and interpretation. The following checklist provides key considerations for establishing a role for specific ROS in biological processes [9]:

- Identify the specific ROS responsible rather than using "ROS" as a generic term

- Verify chemical plausibility of the proposed reactions

- Confirm appropriate localization and concentration of the ROS or antioxidant

- Demonstrate functional impact of altering ROS levels or oxidative modifications

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Redox Signaling Studies

Critical Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Redox Signaling Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Probes | Genetically encoded HyPer, roGFP; DCFH-DA, DHE | Dynamic, compartment-specific ROS measurement; general oxidative stress assessment | Specificity varies (HyPer for H₂O₂; roGFP for redox potential); artifacts common with chemical probes |

| ROS Modulators | NOX inhibitors (apocynin, VAS2870); SOD mimetics; Catalase | Modulate specific ROS pathways; test functional involvement | Verify specificity and efficacy; SOD mimetics often have lower activity than endogenous SOD |

| Thiol Modifiers | N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), iodoacetamide (IAM) | Alkylate free thiols to preserve redox state during sample processing | Use appropriate controls; ensure complete alkylation |

| Antioxidants | N-acetylcysteine (NAC), Tempol, Vitamin E | Test antioxidant effects; modulate redox state | NAC acts mainly as cysteine precursor, not direct H₂O₂ scavenger; multiple effects possible |

| Redox Biosensors | Biotin-switch techniques, redox Western blotting | Detect specific protein modifications (S-nitrosylation, glutathionylation) | Multiple controls needed; potential false positives |

| Genetic Tools | siRNA/shRNA, CRISPR/Cas9, transgenic animals | Modulate expression of redox system components | Consider compensation and developmental effects |

Recent advances in genetically encoded fluorescent redox probes allow dynamic, real-time measurements of defined redox species with subcellular compartment resolution in intact living cells [10]. These tools have revolutionized our understanding of redox homeodynamics by enabling researchers to monitor spatiotemporal patterns of redox signaling rather than static snapshots.

When using pharmacological tools, careful interpretation is essential. For example, N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is widely described as an antioxidant but directly scavenges H₂O₂ very slowly; many of its effects likely result from increasing cellular thiol levels or reducing disulfide bridges in cell surface receptors [9]. Similarly, the biological activity of SOD mimetics should be verified to significantly increase total SOD activity above endogenous levels before concluding that superoxide depletion mediates observed effects [9].

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Perspectives

Disruption of redox homeodynamics contributes to numerous pathological conditions. In neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, oxidative damage accumulates due to the brain's high oxygen consumption, abundance of oxidizable substrates, and relatively weak antioxidant defenses [11] [13]. In the cardiovascular system, NADPH oxidase-derived ROS contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and atherosclerosis [13]. Cancers often display altered redox regulation, with increased ROS production driving proliferation while adaptive upregulation of antioxidant systems promotes survival [8].

Therapeutic strategies targeting redox systems include:

- Nrf2 Activators: Compounds that promote Nrf2 dissociation from Keap1 to enhance antioxidant gene expression

- NOX Inhibitors: Specific inhibitors of pathological ROS production

- Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants: Compounds like MitoQ that accumulate in mitochondria

- Redox Modulators: Agents that selectively increase ROS in cancer cells to exceed toxic thresholds

The dual role of ROS as both signaling molecules and damaging agents creates therapeutic challenges, as global antioxidant supplementation may disrupt beneficial redox signaling while attempting to reduce oxidative damage [5]. Future therapeutic approaches will likely require precise spatiotemporal modulation of specific redox pathways rather than general antioxidant approaches.

The molecular players in redox signaling—ROS, RNS, GSH, thioredoxin, and NADPH systems—function within an integrated framework of redox homeodynamics that maintains functional stability through dynamic interactions and continuous adjustment. Understanding the specific roles, compartmentalization, and regulatory relationships among these systems provides crucial insights into both physiological regulation and pathological mechanisms. Future research emphasizing spatiotemporal resolution of redox processes and their integration with other signaling networks will advance both fundamental understanding and therapeutic applications of redox biology.

The concept of redox homeostasis as a simple, static balance has evolved into the more dynamic paradigm of redox homeodynamics, which portrays redox regulation as a continuous, adaptive signaling process. Central to this framework is the "Redox Code," a set of principles governing how specific, reversible chemical modifications on cysteine residues transduce cellular signals to regulate metabolism, gene expression, and cell fate. This whitepaper delves into the molecular machinery of thiol-based redox switches, focusing on the mechanisms of reversible cysteine oxidative post-translational modifications (PTMs) and their role in health and disease. We provide a detailed examination of the core signaling mechanisms, supported by summarized quantitative data, experimental protocols for key assays, and visualizations of critical pathways. Furthermore, we explore the therapeutic implications of targeting the redox code, offering a toolkit for researchers and drug developers aiming to intervene in pathologies driven by redox dysregulation, from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases.

The traditional view of redox homeostasis as a simple steady-state balance between oxidants and antioxidants has been refined by the concept of redox homeodynamics. This modern paradigm emphasizes that the redox state is not a static set-point to be maintained, but a dynamic, actively signaling interface that continuously adapts to metabolic and environmental challenges [14] [3]. This dynamic equilibrium, or nucleophilic tone, is preserved through continuous feedback signaling for the production and elimination of electrophiles and nucleophiles [3].

Underpinning this redox homeodynamics is the Redox Code, a set of principles that includes the regulation of NADH and NADPH systems in metabolism and the dynamic control of thiol switches in the redox proteome [15]. The code is written primarily through the chemistry of cysteine thiols, which act as molecular sensors and transducers. The redox-sensitive proteome, or redoxome, with its network of cysteine-sensitive proteins—the cysteinet—serves as the hardware upon which this code is executed [16]. These proteins are fundamental for maintaining cellular redox balance and controlling signaling in response to changes in the redox environment. Understanding this code is paramount, as its dysregulation is a hallmark of a wide array of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic syndromes [15] [16].

The Molecular Basis of the Redox Code: Cysteine Chemistry and Compartmentalization

Cysteine as a Redox-Sensitive Molecular Switch

The sulfur atom of a cysteine residue is uniquely versatile in its chemistry. Its thiol (-SH) side chain can undergo a wide spectrum of reversible oxidative post-translational modifications, making it an ideal molecular switch analogous to phosphorylation [17]. The reactivity of a specific cysteine is dictated by its local protein microenvironment. A key determinant is its acidity (pKa); cysteines with a low pKa (4–5) exist as a reactive thiolate anion (S-) at physiological pH, making them uniquely susceptible to oxidation compared to cysteines with a typical pKa of 8.5 [18] [17].

The following table summarizes the major reversible cysteine modifications involved in redox signaling:

Table 1: Major Reversible Cysteine Oxidative Post-Translational Modifications

| Modification | Inducing Species | Chemical Designation | Key Regulatory Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-Nitrosylation [18] | NO, S-nitrosothiols | SNO | GSNO Reductase [18] |

| S-Glutathionylation [18] | ROS, reactive intermediates | PSSG | Glutaredoxin (Grx) [18] |

| Disulfide Bond [19] | ROS | S-S | Thioredoxin (Trx), Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) [18] |

| Sulfenic Acid [19] | H₂O₂ | SOH | Peroxiredoxins, subsequent reactions |

| S-Sulfhydration [17] | H₂S derivatives | SSH | Not Specified |

| Sulfinic Acid [18] | ROS | SO₂H | Sulfiredoxin (ATP-dependent) [18] |

These modifications function as molecular switches that can drastically alter protein function, location, and interaction partners. Distinct modifications can lead to unique functional outcomes, allowing a single cysteine to process different redox signals into specific cellular responses [18]. For instance, sulfenic acid formation in protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) leads to their inactivation, thereby promoting phosphorylation-dependent signaling cascades [19].

Compartmentalization of Redox Potential

A critical feature of redox homeodynamics is the stark compartmentalization of the redox potential within the cell. This compartmentalization ensures that redox signals are spatially constrained, adding specificity to the redox code.

Table 2: Redox Compartmentalization in Eukaryotic Cells

| Cellular Compartment | Redox Environment (Eh GSSG) | Key Characteristics and Players |

|---|---|---|

| Cytosol / Nucleus [17] | Highly Reducing (-150 to -200 mV) | Reduced by GSH, Grx, Trx. Disulfide formation is unfavorable. |

| Mitochondria [17] | Highly Reducing (-150 to -200 mV) | Major source of ROS (e.g., Complex I, III). High GSH and Trx2. |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum [17] | Oxidizing (-170 to -185 mV) | Specialized for disulfide bond formation via Ero1, PDI, QSOX. |

| Extracellular Space [17] | Oxidizing (-80 to -150 mV) | More oxidizing milieu, stable disulfide bonds. |

This compartmentalization dictates the type of redox modifications that can occur. The cytosol and nucleus are optimized for transient, reversible signaling modifications like S-nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation, whereas the ER is specialized for the formation of structural disulfide bonds in secretory and membrane proteins [17].

Figure 1: The Cysteine Redox Switch Network. Cysteine thiols, particularly in their reactive thiolate form (S⁻), can be oxidized by various reactive species to form different reversible post-translational modifications. A network of specific reductase enzymes returns the oxidized cysteine to its reduced state, completing the catalytic cycle that forms the basis of redox signaling. Key: RNS, Reactive Nitrogen Species; GSSG, Oxidized Glutathione; ROS, Reactive Oxygen Species; Trx, Thioredoxin; Grx, Glutaredoxin; GSNOR, S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase; PDI, Protein Disulfide Isomerase. Adapted from [18] [16] [17].

Physiological and Pathophysiological Roles of Thiol Switches

Regulation of Signal Transduction Pathways

Redox signaling via cysteine switches is a main feature of signal transduction downstream of a vast array of receptors, including receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), and cytokine receptors [18] [19]. A classic example is the reversible inactivation of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases (PTPs). The catalytic cysteine of PTPs has a low pKa and is highly susceptible to oxidation by H₂O₂ generated in response to growth factor stimulation. Formation of sulfenic acid reversibly inactivates the phosphatase, thereby prolonging the phosphorylation and activation of kinase signaling cascades [19]. This mechanism ensures that physiological levels of H₂O₂ act as a second messenger to amplify mitogenic signals.

Another key regulatory mechanism involves the redox-dependent switch of Peroxiredoxins (Prx). These major antioxidant enzymes can shift from acting as peroxidases to functioning as molecular chaperones upon overoxidation. This functional switch, triggered by high levels of H₂O₂, allows localized H₂O₂ accumulation to facilitate signaling to proteins like the transcription factor HIF1α while simultaneously preparing the cell to handle stress-induced protein unfolding [19].

Mitochondrial Redox Signaling

Mitochondria are critical hubs for redox signaling, with several physiological processes being initiated by a transient redox burst from the electron transport chain (ETC) [20]. Key mechanisms of elevated superoxide/H₂O₂ production include:

- Reverse Electron Transport (RET): Driven by succinate accumulation, leading to superoxide production at Complex I, which signals in contexts like hypoxia-reperfusion and thermogenesis [20].

- Cytochrome c retardation: Slowing of electron flow at Complex III, a key mechanism for initiating HIF1α stabilization during hypoxia [20].

- Fatty acid oxidation: Electron transfer flavoprotein: coenzyme Q oxidoreductase (ETFQOR) generates superoxide during elevated fatty acid oxidation, which can stimulate insulin secretion [20].

This mitochondrial redox signal is then relayed, often via peroxiredoxins, to specific extramitochondrial targets, enabling processes such as the regulation of transcription factors (e.g., HIF1α, PGC1α), immune cell activation, and metabolic adaptation [20].

Redox Dysregulation in Disease

Dysregulation of the redox code is implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases. In neurodegenerative diseases such as Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's, redox dysregulation and oxidative stress lead to aberrant cysteine PTMs on key proteins. This can result in protein misfolding, aggregation, and neuronal dysfunction, forming a "cysteinet" that drives pathology [16]. For example, S-nitrosylation of protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) can inhibit its chaperone activity, contributing to the accumulation of misfolded proteins [16].

In cancer, redox signaling promotes tumor progression and metastasis. For instance, knockdown of the antioxidant enzyme GPx2 in a breast cancer model creates a redox signal that stabilizes HIF1α. This, in turn, activates the transcription factor p63, driving a hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal (E/M) phenotype and metabolic reprogramming towards oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), ultimately facilitating metastasis [21]. This highlights how targeted redox dysregulation can orchestrate complex phenotypic and metabolic switches in cancer.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Studying the redox code requires a specialized set of tools to detect, quantify, and manipulate specific cysteine modifications and their functional consequences.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Methods for Redox Biology Research

| Reagent / Method | Function / Target | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Biotin-Switch Assay [18] | Specific detection of S-nitrosylation (SNO). | Proteins are initially blocked, SNO bonds are selectively reduced (e.g., with ascorbate), and newly freed thiols are biotinylated for pull-down. |

| Dimedone & Probes [19] | Chemical probes that specifically trap sulfenic acids (SOH). | Allows for direct labeling and detection of this often transient intermediate. Critical for studying PTP and kinase regulation. |

| Antibodies vs. Oxidized Cys | Immunodetection of specific PTMs (e.g., SO₂H, SNO). | Commercially available antibodies enable Western blot and IHC detection, though specificity must be validated. |

| Redox-Sensitive GFP (roGFP) [15] | Real-time, live-cell measurement of redox potential. | Genetically encoded sensor that ratiometrically reports the glutathione redox potential (Eh) in specific cellular compartments. |

| MS-based Redox Proteomics [18] [16] | Global, unbiased mapping of cysteine oxidation states. | Involves blocking free thiols, reducing specific PTMs, and labeling newly freed thiols with isotopic tags for mass spectrometry (MS) identification/quantification. |

| siRNA/CRISPR for Redox Enzymes [21] | Functional studies of redox regulators (e.g., GPx2, Trx, GSNOR). | Used to dissect the role of specific enzymes in controlling redox signaling nodes in disease models like cancer. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Mapping the Redox Proteome

For researchers aiming to conduct a global analysis of the "cysteinet," the following workflow, based on modern mass spectrometry (MS) approaches, is considered a gold standard.

Objective: To identify and quantify reversible cysteine oxidation events across the proteome in response to a specific stimulus (e.g., H₂O₂, growth factors).

Workflow:

Cell Lysis with Alkylation: Rapidly lyse cells in a buffer containing a strong alkylating agent (e.g., Iodoacetamide, IAM; or N-ethylmaleimide, NEM) to block all free, reduced thiols. This "caps" the basal reduced state of cysteines and prevents post-lysis oxidation artifacts.

PTM-Specific Reduction: Divide the lysate. In one sample, treat with a reagent that selectively reduces the PTM of interest. For example:

- S-nitrosylation: Use ascorbate/copper to selectively reduce S-NO bonds to free thiols.

- Disulfides/S-glutathionylation: Use a specific reducing agent like Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) or DTT.

- Sulfenic Acid: Use a probe-labeled dimedone derivative that has been conjugated to a tag like biotin after the initial trapping step.

Tagging of Newly Freed Thiols: After the selective reduction step, the newly exposed thiols, which represent previously oxidized cysteines, are labeled with a distinct isotopic tag. The most common method is using IodoTMT or similar tandem mass tag (TMT) reagents that enable multiplexed quantification.

Combination, Digestion, and Enrichment: Combine the differentially labeled samples. Digest the proteins with trypsin. Enrich for the tagged, previously oxidized peptides using anti-TMT antibodies or streptavidin beads (if a biotin-based method was used in step 2).

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Analyze the enriched peptides by LC-MS/MS. The isotopic tags allow for precise relative quantification of the oxidation level of specific cysteine sites across different experimental conditions.

Data Analysis: Use bioinformatic tools to identify the proteins and specific cysteine residues that showed significant changes in oxidation, mapping them onto pathways and functional networks.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Redox Proteomics. This diagram outlines the key steps for a quantitative mass spectrometry-based experiment to map specific cysteine oxidative post-translational modifications (PTMs) across the proteome, such as the biotin-switch technique and related methods. LC-MS/MS, Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry; IAM, Iodoacetamide; SNO, S-Nitrosylation. Adapted from [18] [16].

Therapeutic Targeting of the Redox Code

The intricate role of redox signaling in disease makes it an attractive therapeutic arena. Strategies are moving beyond broad-spectrum antioxidants to targeted approaches that aim to reset specific dysregulated nodes in the redox network.

Current and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

Small Molecule Inhibitors: Emerging therapies focus on developing small molecule inhibitors that target specific cysteine residues in redox-sensitive proteins. These compounds have demonstrated promising outcomes in preclinical models, setting the stage for forthcoming clinical trials [15]. For example, targeting the redox-sensitive transcription factor NRF2, the "master regulator" of the antioxidant response, is a active area of research for cancer and inflammatory diseases [15].

Modulating Redox-Sensitive Nodes in Cancer: The example of GPx2 in breast cancer provides a mechanistic basis for therapeutic intervention. In this context, GPx2 loss creates a dependency on HIF1α signaling for metastasis. Experimental Approach: To validate this, researchers can treat GPx2-knockdown tumor-bearing mice with a HIF1α inhibitor like echinomycin. The protocol involves monitoring tumor growth and quantifying lung metastases, with results demonstrating that HIF1α loss or GPx2 overexpression reverses the metastatic phenotype [21]. This confirms HIF1α as a druggable target in this specific redox-context.

Challenges and Precision Medicine: The failure of broad-spectrum antioxidants in complex diseases underscores the need for precision. The therapeutic goal is not global antioxidant suppression but the precise re-establishment of redox balance in specific cellular compartments or pathways [15] [3]. This requires a deep, context-specific understanding of redox signaling in each disease.

Figure 3: Targeting a Redox Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer Metastasis. This pathway, elucidated through single-cell transcriptomics, shows how knockdown of Glutathione Peroxidase 2 (GPx2) creates a redox signal that stabilizes HIF1α, activating p63 and driving a metastatic hybrid epithelial/mesenchymal (E/M) state. The diagram highlights two successful therapeutic intervention points: HIF1α inhibition and GPx2 overexpression, both of which suppress metastasis in experimental models [21].

The framework of redox homeodynamics has revolutionized our understanding of redox biology, positioning it as a dynamic, information-rich signaling system rather than merely a battle against oxidative damage. The Redox Code, executed through reversible cysteine modifications, represents a fundamental language of cellular communication that integrates metabolic status, environmental cues, and transcriptional responses. The experimental and therapeutic landscape in redox biology is rapidly advancing, driven by sophisticated proteomic tools and a more nuanced understanding of context-specific redox signaling. The future of targeting the redox code lies in the development of precise, mechanism-based therapeutics that can modulate specific thiol switches to restore physiological redox homeodynamics in a wide range of human diseases.

Within cellular biology, the conceptual framework is evolving from static redox homeostasis toward redox homeodynamics, emphasizing the dynamic, adaptive, and signaling roles of redox processes. This whitepaper elucidates how the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway and PGC-1α function as central sensors and effectors within this paradigm. Nrf2 orchestrates a rapid, inducible antioxidant response, while PGC-1α governs mitochondrial biogenesis and function, ensuring long-term metabolic adaptation. Critically, these systems are not isolated; they engage in extensive crosstalk, forming a resilient regulatory network that maintains cellular integrity in the face of metabolic and oxidative challenges. Understanding this intricate interplay provides a sophisticated foundation for novel therapeutic strategies in drug development targeting age-related diseases, metabolic disorders, and cancer.

The traditional view of redox homeostasis implies a static equilibrium in the balance between oxidants and antioxidants. However, contemporary research underscores that redox processes are inherently dynamic, acting as continuous signaling mechanisms that can be smoothly modulated to support physiological functions and adaptive responses [3]. This dynamic equilibrium, or redox homeodynamics, involves constant feedback to preserve nucleophilic tone, which is essential for a healthy physiological state [3]. Within this framework, electrophiles and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are not merely damaging agents but serve as specific molecular messengers in cellular signaling [22]. A key feature of homeodynamics is hormesis, where mild stress triggers adaptive beneficial responses, and parahormesis, where certain nutritional phytochemicals mimic these effects by activating pathways like Nrf2 to support homeostasis [3]. This paper explores the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway and PGC-1α as quintessential sensors and effectors within the paradigm of redox homeodynamics.

The Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway: A Sensor for Electrophilic Stress

Molecular Regulation of the Nrf2-Keap1 Axis

The Nrf2-Keap1 system is a primary cellular defense mechanism against electrophilic stress and oxidative challenge. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is continuously ubiquitinated and targeted for proteasomal degradation by its negative regulator, Keap1, a substrate adaptor for a Cullin 3-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex [23]. Keap1 is a cysteine-rich protein that acts as a sensitive redox sensor. Upon exposure to oxidants or electrophiles, specific cysteine residues in Keap1 are modified, leading to a conformational change that inhibits its E3 ligase activity [23]. This results in Nrf2 stabilization, its translocation to the nucleus, and heterodimerization with small MAF (sMAF) proteins. The heterodimer binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), activating the transcription of a vast network of over 200 genes involved in antioxidant defense, detoxification, and NADPH regeneration [24] [23]. The system is designed for rapid activation and deactivation, ensuring a dynamic and responsive defense.

Experimental Analysis of the Nrf2 Pathway

Studying the Nrf2 pathway requires methodologies to assess its activation, downstream effects, and functional outcomes. Key experimental approaches are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Experimental Methodologies for Investigating the Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway

| Methodology | Key Objective | Example Application & Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Proteomics | Identify oxidative modifications on protein cysteine residues. | Revealed redox changes in 403 proteins in AZA-resistant leukemic cells, implicating the SQSTM1-KEAP1-NRF2 pathway in drug resistance [25]. |

| ARE-Luciferase Reporter Assay | Measure Nrf2 transcriptional activity. | Used in vitro and in vivo to screen for Nrf2 activators (e.g., sulforaphane) and quantify pathway induction [23]. |

| GSH/GSSG Ratio Measurement | Assess the cellular redox state. | Flow cytometry revealed a more oxidized state and higher GSH in 5-azacytidine (AZA)-resistant MDS/AML cells [25]. |

| Keap1 Inhibitor Studies | Functionally validate Nrf2 dependence. | KEAP1 inhibition re-sensitized AZA-resistant cells to treatment and improved survival in mouse xenograft models [25]. |

| ChIP-Seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation) | Map genome-wide Nrf2 binding sites. | Identifies direct Nrf2 target genes and ARE locations in specific cell types [24]. |

Figure 1: The Nrf2-Keap1 Signaling Pathway. Under basal conditions, Keap1 targets Nrf2 for degradation. Oxidative stress modifies Keap1 cysteine residues, leading to Nrf2 stabilization, nuclear translocation, and activation of cytoprotective gene expression.

PGC-1α: A Master Regulator of Mitochondrial and Redox Homeodynamics

PGC-1α as an Integrative Coactivator

PGC-1α is a transcriptional coactivator identified as a master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and function [26]. It does not bind DNA directly but serves as a modular scaffolding platform, interacting with and coactivating a wide range of transcription factors in response to environmental and intracellular cues [27] [26]. Through its interactions with nuclear respiratory factors (NRF1 and NRF2), and ERRα, PGC-1α drives the expression of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes, including those for the electron transport chain (ETC), and key factors like TFAM, which is essential for mitochondrial DNA transcription and replication [28]. Consequently, PGC-1α is a central effector for enhancing oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and cellular energy capacity.

Regulation of PGC-1α Expression and Activity

PGC-1α is regulated at multiple levels, allowing for precise control over its activity:

- Transcriptional Regulation: Key upstream transcription factors include CREB (activated by cAMP/PKA signaling in response to glucagon or cold), MEF2, and ATF2 (activated by p38 MAPK signaling) [27] [28]. Intracellular calcium influx, such as during muscle contraction, activates CaMKIV, which also promotes PGC-1α expression via CREB [28].

- Post-Translational Modifications: These critically fine-tune PGC-1α's activity and stability. Key activating modifications include phosphorylation by p38 MAPK and AMPK, and deacetylation by SIRT1 in low-energy states (high NAD+ levels) [27] [28]. Conversely, acetylation by GCN5 and phosphorylation by AKT or GSK3β inhibit PGC-1α or promote its degradation [27] [28].

Table 2: Key Regulatory Inputs and Modifications of PGC-1α

| Regulator | Effect on PGC-1α | Physiological Context |

|---|---|---|

| CREB | Increased transcription | Fasting, cold exposure, exercise [28]. |

| p38 MAPK | Increased transcription and phosphorylation (activation) | Cellular stress, exercise [27] [28]. |

| AMPK | Phosphorylation (activation) | Low energy status (high AMP/ATP ratio) [28]. |

| SIRT1 | Deacetylation (activation) | Low energy status (high NAD+), fasting [27]. |

| AKT/GSK3β | Phosphorylation (inhibition/degradation) | Insulin signaling [27]. |

| NF-κB | Repressed expression and activity | Inflammation [26]. |

PGC-1α in Redox Metabolism

Beyond its role in mitochondrial biogenesis, PGC-1α is a pivotal regulator of the cellular antioxidant response. It directly controls the expression of major mitochondrial and cytosolic antioxidant enzymes, including manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD/SOD2), catalase, peroxiredoxin 3/5, uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2), and thioredoxin 2 [27]. By enhancing the mitochondrial membrane potential and OXPHOS, PGC-1α can also influence the primary site of ROS generation. Therefore, PGC-1α acts as a key node, dynamically coordinating energy production with the capacity to manage its potentially harmful redox byproducts, a core principle of homeodynamics.

Interplay and Crosstalk between Nrf2 and PGC-1α Signaling

The relationship between Nrf2 and PGC-1α is a quintessential example of homeodynamic crosstalk. Rather than operating in isolation, these pathways form a regulatory loop that ensures a coordinated adaptation to metabolic and oxidative demands [28].

- PGC-1α as a Downstream Effector of Nrf2: Nrf2 activation can promote mitochondrial biogenesis by upregulating the expression of NRF1 (a nuclear respiratory factor), which is a key binding partner for PGC-1α [28]. This creates a direct molecular link from the antioxidant response to the enhancement of mitochondrial capacity.

- Nrf2 as a Target of PGC-1α-Regulated Metabolism: Conversely, the metabolic shifts driven by PGC-1α influence the redox environment. Increased mitochondrial flux can elevate ROS production, which in turn can serve as a signaling molecule to activate the Nrf2 pathway [28]. This creates a feedback loop where an increase in metabolic capacity is matched by an enhanced antioxidant capability.

- Shared Upstream Regulators: Both pathways are influenced by common sensors of cellular energy and stress. For instance, AMPK not only activates PGC-1α but can also phosphorylate and activate Nrf2 [23]. Similarly, p38 MAPK signaling positively regulates both factors [27] [23].

This intricate crosstalk underscores the system's robustness, allowing the cell to mount a unified and adaptive response to maintain homeodynamics.

Figure 2: Crosstalk between the Nrf2 and PGC-1α Pathways. Shared upstream regulators like AMPK and p38 MAPK coregulate Nrf2 and PGC-1α. Nrf2 can promote mitochondrial biogenesis via NRF1, while PGC-1α-driven metabolism can generate ROS signals that feedback to activate Nrf2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Studying Redox Homeodynamics

| Reagent / Model | Function/Application | Key Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KEAP1 Inhibitors | Pharmacologically disrupt Nrf2-Keap1 interaction to study Nrf2 activation. | e.g., ML334, RTA-408; used to re-sensitize AZA-resistant cancer cells [25]. |

| Nrf2 Activators | Induce the antioxidant response pathway. | Sulforaphane, CDDO-Me; used to study cytoprotection and potential in metabolic diseases [23]. |

| SIRT1 Activators | Mimic low-energy state to activate PGC-1α via deacetylation. | Resveratrol, SRT1720; important for studying mitochondrial adaptation and energy metabolism [27]. |

| PGC-1α Expression Constructs | Overexpress or knock down PGC-1α to determine its functional role. | Adenoviral or lentiviral vectors for gain/loss-of-function studies in vitro and in vivo [26]. |

| ARE-Luciferase Reporter | Quantify Nrf2 transcriptional activity in high-throughput screens. | Cell lines stably transfected with ARE-driven luciferase construct [23]. |

| AZA-Resistant Cell Lines | Model of acquired chemoresistance linked to redox reset. | MDS/AML OCI-M2 clones with altered KEAP1-NRF2 signaling and redox state [25]. |

| CdX Mouse Models | In vivo validation of pathway mechanisms and therapeutic efficacy. | Immunodeficient mice transplanted with AZA-R cells to test KEAP1 inhibitor efficacy [25]. |

The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway and PGC-1α are master regulators that epitomize the concept of redox homeodynamics. Their roles as sensors and effectors, their multi-layered regulation, and their extensive crosstalk create a dynamic and resilient network that allows the cell to adapt to a constantly changing environment. Moving forward, several key areas will shape future research and therapeutic development:

- Targeting Pathway Crosstalk: Therapeutic strategies should consider the interconnected nature of these pathways. For example, in inflammatory diseases where NF-κB suppresses PGC-1α [26], combined activation of PGC-1α and Nrf2 may offer synergistic benefits.

- Overcoming Drug Resistance: The discovery that AZA resistance in MDS/AML is mediated by a redox reset involving KEAP1-NRF2 [25] opens new avenues for combination therapies, using KEAP1 inhibitors to re-sensitize tumors to existing drugs.

- Precision Modulation: A major challenge is achieving tissue- and context-specific modulation. The development of more targeted activators and a deeper understanding of the differential regulation of PGC-1α splice variants [26] will be crucial for minimizing off-target effects.

In conclusion, framing these regulatory systems within the dynamic concept of homeodynamics provides a more powerful and accurate model for understanding cellular resilience, aging, and disease pathogenesis, ultimately guiding the development of next-generation therapeutics.

Redox homeostasis, the delicate balance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and elimination, is fundamental to cellular health. This whitepaper explores the concept of redox homeodynamics—the dynamic, adaptive nature of redox regulation—and its critical shift toward redox dyshomeostasis in pathological states. We provide a technical analysis of how the loss of redox control drives pathogenesis in cardiovascular diseases (CVD), neurodegenerative disorders (NDDs), and neoplastic diseases through shared yet context-specific mechanisms. By integrating current research findings, structured quantitative data, detailed experimental methodologies, and visual signaling pathways, this guide serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals targeting redox-based therapeutic strategies.

The traditional concept of redox homeostasis implies a static equilibrium, whereas contemporary understanding emphasizes redox homeodynamics—a dynamic, adaptive interplay between pro-oxidant generation and antioxidant defense that maintains functional stability in biological systems [15]. This sophisticated regulatory network ensures that reactive oxygen species (ROS), once considered merely toxic metabolic byproducts, can function as crucial redox signaling molecules at physiological concentrations [29] [30].

Redox dyshomeostasis occurs when this dynamic balance is disrupted, leading to either oxidative stress (excess ROS) or reductive stress (excess antioxidants) [29] [31]. This imbalance triggers molecular damage and aberrant signaling, establishing a common pathological foundation across diverse disease states. The dual nature of ROS as both signaling molecules and damaging agents creates a context-dependent therapeutic challenge [29] [31]. In the transition from homeodynamics to dyshomeostasis, several core mechanisms are repeatedly engaged:

- Mitochondrial dysfunction leading to altered ROS production

- Dysregulated NRF2 signaling, a master regulator of antioxidant response

- Altered redox-sensitive pathways (NF-κB, MAPK)

- Epigenetic modifications and post-translational changes to proteins [15]

The following sections detail how these mechanisms manifest in cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and neoplastic diseases, providing a comparative framework for understanding disease-specific and shared therapeutic targets.

Redox Dyshomeostasis in Cardiovascular Diseases

In the cardiovascular system, redox homeodynamics is precisely regulated, with ROS serving as vital signaling molecules for normal vascular function. The shift toward dyshomeostasis involves hyperactivation of oxidant sources and impaired antioxidant defense, contributing fundamentally to endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and cardiac remodeling.

Molecular Mechanisms and Pathological Consequences

Table 1: Major ROS Sources and Their Roles in Cardiovascular Pathology

| ROS Source | Localization | Primary ROS | Cardiovascular Pathological Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADPH Oxidases (Nox) | Vascular cell membranes | Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Primary signaling ROS source; activated by AngII, TNF-α; drives hypertrophy & endothelial dysfunction [30] |

| Mitochondrial ETC | Mitochondrial inner membrane | Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Electron leak during oxidative phosphorylation; enhanced in cardiac hypertrophy & I/R injury [32] [30] |

| Uncoupled eNOS | Endothelium | Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiency converts eNOS from •NO to O₂•⁻ production; promotes atherosclerosis [30] |

| Xanthine Oxidase | Cytoplasm | Superoxide (O₂•⁻), H₂O₂ | Purine metabolism; contributes to endothelial dysfunction and heart failure [30] |

Mitochondrial sirtuins (SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5) function as crucial redox sensors in CVD, linking cellular metabolic status to oxidative stress responses. These NAD+-dependent enzymes are dysregulated under nutrient excess, creating a vicious cycle of mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production [32]. SIRT3 in particular regulates key antioxidant pathways by deacetylating and activating mitochondrial enzymes like superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) [32].

ROS directly impact cardiovascular function through redox-sensitive post-translational modifications of cysteine thiols in proteins critical for contractility, calcium handling, and signaling. Key modifications include:

- S-glutathionylation: Reversible disulfide formation between glutathione and protein thiols regulating proteins like sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺ ATPase (SERCA) and ryanodine receptors [30]

- S-nitrosylation: •NO-dependent modification regulating caspase activity and apoptosis [30]

- Sulfenic acid formation: Initial oxidation product that can progress to irreversible oxidation [30]

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Protocol 1: Measuring Mitochondrial ROS Production in Cardiac Tissue

- Tissue Preparation: Fresh cardiac tissue (50-100mg) minced in ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer (250mM sucrose, 10mM HEPES, 1mM EGTA, pH 7.4)

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Differential centrifugation at 4°C: 800g for 10min (discard pellet), 10,000g for 10min (mitochondrial pellet)

- ROS Detection: Resuspend mitochondria in respiration buffer with 5μM MitoSOX Red; incubate 15min at 37°C

- Stimuli Testing: Add substrates (succinate/glutamate) with/without inhibitors (antimycin A/rotetone)

- Quantification: Measure fluorescence (excitation/emission: 510/580nm) and normalize to mitochondrial protein content [32] [30]

Protocol 2: Assessing Vascular Redox Status via NADPH Oxidase Activity

- Vessel Homogenization: Pulverize frozen vessels under liquid N₂, homogenize in lysis buffer with protease inhibitors

- Membrane Fraction Isolation: Centrifuge at 100,000g for 45min at 4°C

- Activity Assay: Incubate membrane fraction with NADPH (100μM), lucigenin (5μM) in assay buffer

- Kinetic Measurement: Monitor chemiluminescence for 30min; specificity confirmed with diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) inhibition

- Normalization: Express activity as relative light units/min/mg protein [30]

Redox Dyshomeostasis in Neurodegenerative Diseases

The brain's high metabolic rate and lipid-rich environment make it particularly vulnerable to redox dyshomeostasis. In neurodegenerative diseases, a gradual shift from adaptive redox signaling to chronic oxidative damage drives neuronal loss through distinct yet overlapping mechanisms.

Mechanisms of Oxidative Vulnerability

Table 2: Redox Dysregulation in Major Neurodegenerative Diseases

| Disease | Primary Redox Features | Key Affected Pathways | Oxidative Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease | Mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress, impaired Nrf2 signaling, heme dysregulation [33] [34] | GSK3β-Nrf2 interaction, p38 MAPK, NF-κB | Increased protein & lipid oxidation in brain tissue, 4-hydroxynonenal [29] [35] |

| Parkinson's Disease | Mitochondrial complex I deficiency, dopamine oxidation, diminished Nrf2 activity [33] | DJ-1/PARK7, PINK1/Parkin, Nrf2-ARE | Protein carbonyls, lipid peroxidation in substantia nigra [33] [35] |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | SOD1 mutations, excessive NOX activity, disrupted RSS signaling [33] | TDP-43 pathology, ER stress, NF-κB | Elevated CSF 8-OHdG, nitrotyrosine modifications [33] |

The NRF2-KEAP1 pathway is particularly critical in NDDs, with declining Nrf2 activity observed in aging brains and neurodegenerative conditions [29] [35]. This master regulator coordinates the expression of over 250 cytoprotective genes; its impairment leaves neurons vulnerable to oxidative insults. The GSK3β enzyme serves as a key endogenous negative regulator of Nrf2, providing a mechanistic link between insulin signaling, autophagy, and redox homeostasis [35].

Post-translational modifications fine-tune redox regulation in the brain through several mechanisms:

- S-sulfhydration: Modification by hydrogen sulfide that can protect against oxidative damage [33]

- CoAlation: Covalent modification by coenzyme A that protects cysteine residues from overoxidation, particularly relevant to tau protein in Alzheimer's disease [35]

- m6A RNA methylation: Redox-sensitive epigenetic modification regulating spinal cord injury responses [35]

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Protocol 3: Assessing Mitochondrial Function in Neuronal Cultures

- Cell Culture: Primary neurons (DIV 10-14) or neuronal cell lines cultured in neurobasal medium with B27 supplement

- Staining: Load cells with 5μM MitoTracker Red CMXRos and 2μM MitoSOX Red in HBSS for 30min at 37°C

- Treatment: Apply disease-relevant stressors (e.g., Aβ oligomers for AD models, rotenone for PD models)

- Imaging: Confocal microscopy with 579nm excitation/599nm emission (MitoTracker) and 510nm excitation/580nm emission (MitoSOX)

- Analysis: Quantify mitochondrial morphology, membrane potential, and ROS production using ImageJ plugins [33] [36]

Protocol 4: Measuring Protein Oxidation in Brain Tissue

- Tissue Homogenization: Homogenize brain regions in RIPA buffer with protease/phosphatase inhibitors

- Protein Carbonyl Detection: Derivatize with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) for 45min at room temperature

- Detection: Separate by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF, incubate with anti-DNP antibody (1:1000)

- Quantification: Normalize to total protein loaded; express as % increase over control [33]

- Alternative Method: For specific proteins, immunoprecipitate target first, then detect carbonyls

Redox Dyshomeostasis in Neoplastic Diseases

Cancer cells exploit redox homeodynamics to support proliferation, survival, and treatment resistance. The "redox adaptation" phenomenon enables neoplastic cells to maintain pro-tumorigenic ROS levels while avoiding cytotoxicity, representing a fundamental shift from physiological redox regulation.

Oncogenic Redox Rewiring

Table 3: Redox Features Across Cancer Hallmarks

| Cancer Hallmark | Redox Regulation | Key Molecular Players | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained Proliferation | Moderate ROS promote growth signaling; reductive stress in some cancers [31] | Growth factor receptors, PI3K/Akt, MAPK | Antioxidants may promote or inhibit depending on context [31] |

| Resisting Cell Death | Upregulated antioxidant systems prevent ROS-mediated apoptosis [31] [37] | Nrf2, Bcl-2, GPX4, GSH | Pro-oxidant therapies to overwhelm defenses [37] |

| Metabolic Reprogramming | ROS regulate HIF-1α, promote glycolysis; metabolic enzymes produce ROS [31] | PKM2, IDH, HIF-1α | Targeting metabolic antioxidant generation (NADPH) [31] |

| Therapy Resistance | Enhanced antioxidant capacity; redox-regulated drug efflux [37] | Nrf2, MRP1, BCRP, MDR1 | Inhibiting antioxidant systems or targeting specific cysteine residues [37] |

The NRF2 pathway demonstrates context-dependent duality in cancer: it prevents carcinogenesis during initiation but promotes tumor progression and therapy resistance once cancer is established [31]. Cancer cells frequently exhibit NRF2 hyperactivation through various mechanisms, including KEAP1 mutations, disrupting the KEAP1-NRF2 interaction, and increased NRF2 transcription [31]. This leads to constitutive expression of antioxidant and detoxification genes that protect cancer cells from oxidative stress and chemotherapeutic agents.

Cancer cells develop multiple redox-dependent resistance mechanisms:

- Altered drug efflux: ROS modify cysteine residues in ABC transporters (MDR1, MRP1, BCRP), affecting their conformation and function [37]

- Enhanced DNA repair: Redox regulation of DNA repair proteins like ATM allows cancer cells to withstand genotoxic stress [15]

- Maintained stemness: CSCs utilize sophisticated antioxidant systems (elevated SOD2, Nrf2 activation) to maintain low ROS and resist therapy [29]

- Metabolic adaptation: Increased pentose phosphate pathway flux generates NADPH to support antioxidant systems [29] [31]

Experimental Assessment Methodologies

Protocol 5: Evaluating NRF2 Activation and Antioxidant Response

- Cell Treatment: Treat cancer cells with NRF2 inducers (sulforaphane, CDDO-Me) or chemotherapeutic agents

- Nuclear/Cytoplasmic Fractionation: Use commercial kits to separate fractions; verify purity with Lamin B1 (nuclear) and GAPDH (cytosolic)

- Western Blotting: Probe with anti-NRF2 antibody (1:1000); quantify nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio

- Gene Expression: Extract RNA, reverse transcribe, perform qPCR for NRF2 targets (NQO1, HO-1, GCLC)

- ARE Reporter Assay: Transfert cells with ARE-luciferase construct; measure luminescence after treatments [31] [37]

Protocol 6: Measuring Glutathione Dynamics in Cancer Cells

- Cell Lysis: Lyse cells in ice-cold PBS with 1% Triton X-100, 0.6% sulfosalicylic acid

- GSH/GSSG Separation: Use commercial GSH/GSSG extraction kits to acidify and stabilize thiols

- Derivatization: Incubate with o-phthalaldehyde (for GSH) or N-ethylmaleimide followed by NaOH (for GSSG)

- Detection: Fluorescence measurement (excitation/emission: 350nm/420nm)

- Calculation: Generate standard curves for GSH and GSSG; calculate GSH:GSSG ratio [31] [37]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Redox Biology Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Detection Probes | MitoSOX Red, H₂DCFDA, Amplex Red | Specific detection of mitochondrial superoxide, general cellular ROS, and extracellular H₂O₂ | Concentration optimization crucial; validate with appropriate controls [33] [30] |

| Antioxidant Response Assays | ARE-luciferase reporters, NRF2 antibodies, KEAP1 mutants | Monitor NRF2 pathway activation, protein localization, and interaction studies | Include both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions for localization studies [31] [15] |

| Thiol Modification Tools | Biotin-switch assays, dimedone-based probes, mass spectrometry | Detect specific oxidative PTMs: S-nitrosylation, sulfenic acids, comprehensive redox proteomics | Preserve labile modifications during sample preparation [33] [30] |

| Mitochondrial Function Assays | Seahorse XF Analyzer kits, JC-1, MitoTracker | Measure OCR, ECAR, membrane potential, and mass | Correlate with ROS measurements for comprehensive assessment [32] [30] |

| Genetic Manipulation Tools | NRF2 siRNA/shRNA, NOX isoform inhibitors, SOD mimetics | Pathway perturbation studies, target validation | Consider compensatory mechanisms in knockout models [31] [37] |

The transition from redox homeodynamics to dyshomeostasis represents a fundamental pathological shift across cardiovascular, neurodegenerative, and neoplastic diseases. While the specific manifestations differ, shared mechanisms include mitochondrial dysfunction, dysregulated NRF2 signaling, and altered redox-sensitive pathways. The intricate duality of ROS—as both essential signaling molecules and damaging agents—demands precisely targeted therapeutic approaches rather than broad antioxidant interventions. Future research must focus on developing disease-specific redox modulators that account for the dynamic, context-dependent nature of redox biology, with particular attention to the timing of intervention and personalized redox profiling. The integrated experimental approaches and comparative analysis presented here provide a framework for advancing these therapeutic strategies.

Quantifying the Flux: Biomarkers and Models for Assessing Redox Homeodynamics