Redox Couples in Electrochemical Sensing: Bridging Molecular Communication and Diagnostic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of redox couples, the cornerstone of electrochemical sensing, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Redox Couples in Electrochemical Sensing: Bridging Molecular Communication and Diagnostic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of redox couples, the cornerstone of electrochemical sensing, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental electron transfer principles that govern the communication between biological systems and electronic devices. The scope spans from foundational theories and the characteristics of conventional and emerging redox probes to advanced methodological applications in pathogen detection, DNA analysis, and clinical diagnostics. The content further addresses critical challenges in real-sample analysis and sensor optimization, culminating in a comparative analysis of sensor validation and performance metrics. This resource aims to guide the development of next-generation, robust electrochemical biosensors for biomedical and clinical research.

The Fundamentals of Redox Communication: Principles and Key Players

Redox reactions, fundamental processes involving the transfer of electrons, have emerged as a powerful natural interface enabling direct communication between biological systems and electronic devices. While electronics utilize moving electrons for information transfer, biological systems rely on molecular signaling. Redox reactions form a unique bridge between these two domains because they facilitate electron transfer processes that can be both biologically meaningful and electronically measurable [1]. This interface is richly elaborated in oxygen-dependent life, where activation/deactivation cycles involving molecules like H₂O₂ contribute to spatiotemporal organization for cellular differentiation, development, and adaptation [2]. The recognition that redox-active molecules participate in reactions at electrode surfaces suggests that electrodes can serve as a pivotal conduit for information exchange, playing a critical role in a wide range of biological processes from protein function to cellular and multicellular communication networks [3]. This foundational principle enables the development of sophisticated biosensing platforms and closed-loop control systems for biological function.

Core Principles of the Redox Code in Bio-Electronic Communication

The operational framework for redox-based communication is defined by a set of principles known as the "Redox Code," which governs the positioning of redox systems in biological systems [2]. The table below outlines the core principles and components of this organizational structure.

Table 1: Principles and Components of the Redox Code in Bio-electronic Communication

| Principle | Core Function | Key Redox Players | Role in Bio-electronic Interface |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Organization | Organizes metabolism via near-equilibrium, thermodynamic control [2] | NAD+/NADH, NADP+/NADP+ [2] | Links cellular metabolic state (catabolism/anabolism) to an electronically readable signal [1] [2] |

| Kinetically Controlled Switches | Links metabolism to protein structure & function via kinetic control [2] | Protein thiols/disulfides, Glutathione (GSH/GSSG) [2] | Provides targets for electronic control of protein activity and cellular signaling pathways [3] |

| Redox Sensing | Enables spatiotemporal sequencing in cell differentiation & life cycles [2] | H₂O₂, Reactive Oxygen Species [2] | Serves as a primary transmission signal for electronic interrogation and actuation of biological responses [1] [3] |

| Networked Adaptation | Forms adaptive systems to respond to environmental changes [2] | Thioredoxin, Nrf2, NF-κB pathways [2] | Allows for electronic feedback control of hierarchical and networked biological systems [3] |

The first principle involves metabolic organization through high-flux, thermodynamically controlled nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD and NADP) systems. The NADH/NAD⁺ couple is central to catabolism and energy supply, while the NADPH/NADP⁺ system is dedicated to anabolism, defense, and control of thiol/disulfide systems [2]. The second principle utilizes kinetically controlled redox switches in the proteome, where reactions of thiols (e.g., cysteine, glutathione) can involve both one-electron and two-electron transfers, determining protein tertiary structure, interactions, and activity [2]. These first two principles create a powerful framework where thermodynamic control (NAD/NADP systems) and kinetic control (thiol systems) work in concert to manage biological information.

Comparative Analysis of Redox Mediators and Couples

The effectiveness of a redox mediator in bio-electronic sensing depends on its electron transfer kinetics, stability, and biocompatibility. The following table provides a quantitative comparison of commonly used and native redox mediators, highlighting their key electrochemical parameters and suitability for different sensing applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Redox Mediators in Electrochemical Sensing

| Redox Mediator | Formal Potential (V vs. Ag/AgCl) | Diffusion Coefficient (cm²/s) | Electron Transfer Rate Constant (k⁰, cm/s) | Key Advantages & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Ferro/Ferricyanide [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | ~+0.22 (in saliva mimic) [4] | ~6.5 × 10⁻⁶ (in saliva mimic on Au) [4] | ~2.0 × 10⁻³ (in saliva mimic on Au) [4] | Well-behaved, fast kinetics. Ideal for probing electrode surface modifications and charge transfer resistance [4]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Reduction: ~0.0 V (varies with electrode) [1] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Native biological signaling molecule. Enables direct interrogation and control of stress responses (e.g., oxyRS regulon) [1] [3]. |

| NADH | Oxidation: ~+0.4-0.7 V (unmodified electrodes) [1] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable | Central metabolic cofactor. Direct measurement indicates metabolic state, though often requires modified electrodes to lower overpotential [1]. |

| Bacterial Phenazines | Varies by specific molecule [1] | Varies by specific molecule | Varies by specific molecule | Natural redox shuttles. Can be enhanced for measurement using graphene-modified electrodes via π-π stacking [1]. |

| Catecholamines | Varies by specific molecule [1] | Varies by specific molecule | Varies by specific molecule | Neurotransmitters. Endogenous molecules relevant to neurological sensing and communication [1]. |

The data reveals a fundamental trade-off between the well-defined, fast kinetics of conventional probes like ferro/ferricyanide and the biological relevance of native mediators like H₂O₂ and NADH. Ferro/ferricyanide provides an excellent benchmark for characterizing electrode performance and sensor integrity, particularly in complex bio-fluids like sweat and saliva where its electron transfer parameters have been rigorously quantified [4]. In contrast, native redox molecules allow for direct monitoring and manipulation of biological processes, albeit often with more complex electrochemistry and requiring sophisticated electrode modifications to achieve selectivity amidst interfering species [1].

Experimental Protocols for Redox-Based Interrogation and Control

Protocol 1: Electro-Biofabrication of Living "Artificial Biofilms"

This methodology enables the spatial assembly of living cells onto electrode surfaces, creating a defined bio-electronic interface for subsequent interrogation and control [3].

Table 3: Key Reagents for Electro-Biofabrication

| Research Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Thiolated Polyethylene Glycol (PEG-SH) | 4-armed monomer that forms a crosslinked hydrogel matrix upon electrochemical oxidation, entrapping cells [3]. |

| Ferrocene (Fc) Mediator | Redox mediator that facilitates the electrochemical oxidation of thiol groups into disulfide bonds for hydrogel cross-linking [3]. |

| Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) Electrode | Optically transparent conductive electrode that allows for simultaneous electronic I/O and visual observation (e.g., confocal microscopy) [3]. |

| Electrode Potentiostat | Instrument to apply a controlled oxidative voltage (e.g., +0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a defined duration (e.g., 2 min) to initiate hydrogel assembly [3]. |

Detailed Workflow:

- Cell Preparation: Mix a culture of E. coli (OD₆₀₀ ~5) with a solution containing 50 mM 4-armed PEG-SH monomer and 5 mM ferrocene redox mediator [3].

- Electro-assembly: Apply an oxidative voltage (+0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 2 minutes) to a patterned gold or ITO working electrode submerged in the cell-polymer mixture [3].

- Film Formation: The applied potential oxidizes ferrocene, which in turn oxidizes PEG-SH thiol groups, forming disulfide bonds that crosslink the hydrogel and entrap cells directly on the electrode surface [3].

- Thickness Control: Vary the deposition time to controllably tune the thickness of the resulting "artificial biofilm." Thickness shows a linear correlation with deposition time [3].

- Validation: Confirm cell viability and functionality post-assembly. For example, measure the secretion of quorum sensing autoinducer AI-2, which should be proportional to the electrode surface area covered by the biofilm [3].

Protocol 2: Redox-enabled Electrogenetic Control of Gene Expression

This protocol uses electrochemically generated hydrogen peroxide to actuate a genetic circuit in engineered E. coli, demonstrating closed-loop electronic control of biological function [3].

Detailed Workflow:

- Genetic Engineering: Rewire the native E. coli oxyRS oxidative stress regulon to control the expression of a gene of interest (e.g., a fluorescent protein like GFP). This is achieved by placing a CRISPR single-guide RNA (sgRNA) under the control of the peroxide-responsive oxyS promoter [3].

- Peroxide Generation: Apply a reducing potential (-0.8 V vs. a suitable reference) to an ITO working electrode in an electrochemical cell containing oxygenated media. This drives the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR: O₂ + 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ → H₂O₂), generating a defined concentration of hydrogen peroxide proportional to the charge passed [3].

- Signal Transmission: The electro-synthesized H₂O₂ diffuses into the culture medium and acts as the redox signal, perceived by the engineered cells as an inducer [3].

- Cellular Reception & Output: H₂O₂ triggers the oxyRS system, activating transcription of the sgRNA. The sgRNA, in conjunction with a CRISPR-activation complex, then drives the expression of the target gene (e.g., GFP) [3].

- Feedback & Quantification: Monitor gene expression output in real-time, for example, by measuring fluorescence. This output can be fed back to the potentiostat to adjust the applied potential/charge, enabling closed-loop control of biological function [3].

The following diagram visualizes this sophisticated signaling and control pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of redox-based bio-electronic interfaces requires a curated set of materials and reagents. The following table details the essential components of a researcher's toolkit for this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Bio-Electrochemistry

| Toolkit Item | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Indium Tin Oxide (ITO), Gold, Platinum, Graphene-modified electrodes [1] [3] | Provides a surface for electron transfer; ITO allows optical transparency; graphene enhances signal for specific molecules like phenazines [1] [3]. |

| Redox Mediators | Ferrocene, Potassium Ferro/Ferricyanide [3] [4] | Facilitates electron transfer in electro-biofabrication (Ferrocene) or serves as a benchmark probe for sensor characterization [3] [4]. |

| Hydrogel Polymers | Thiolated Polyethylene Glycol (PEG-SH), Gelatin-HRP conjugate [3] | Forms a biocompatible matrix for electro-assembly of cells or enzymes onto electrodes, localizing the bio-electronic interface [3]. |

| Native Redox Signals | Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) [1] [3] | Acts as an electronically generated transmission signal to interrogate and control native biological stress response pathways [1] [3]. |

| Engineered Biological Components | E. coli with oxyRS-CRISPRa circuitry, AI-1/LasI reporter plasmids [3] | Provides the genetically encoded receiver and decoder for electronic redox signals, enabling programmable control of complex biological functions like gene expression and quorum sensing [3]. |

Core Principles of Electron Transfer Kinetics in Electrolytes

Electron transfer (ET) kinetics at the electrode-electrolyte interface represent a cornerstone of electrochemical sensing research, dictating the sensitivity, selectivity, and overall performance of sensing platforms. The efficiency of any ET process relies on achieving a desired ET rate within an optimal driving force range [5]. Understanding the core principles governing these kinetics enables researchers to rationally design advanced sensors for applications ranging from environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical analysis. This guide provides a comparative analysis of fundamental ET principles, experimental methodologies, and material systems critical for developing effective electrochemical sensors, with a specific focus on evaluating different redox couples in sensing research.

Marcus theory provides a fundamental microscopic framework for understanding the activation free energy, and thus the rate, of ET in terms of a key parameter: the reorganization energy (λ) [5]. Traditionally, this reorganization energy—the energy required to distort the atomic configuration and solvation environment of reactants to resemble the product state—was thought to originate predominantly from the electrolyte phase. However, recent groundbreaking research has fundamentally challenged this paradigm, demonstrating that the electrode's electronic density of states (DOS) plays a central role in governing the reorganization energy, far outweighing its conventionally assumed role [5]. This paradigm shift has profound implications for the design of electrochemical sensors and the selection of appropriate redox couples and electrode materials.

Theoretical Foundations of Electron Transfer Kinetics

Marcus Theory and Reorganization Energy

The theoretical description of heterogeneous electron transfer kinetics at electrode-electrolyte interfaces has evolved significantly from its initial formulation. The seminal adaptation of the Marcus-Hush model by Chidsey explained the dependence of interfacial ET rates on driving force and temperature by incorporating the Fermi-Dirac distribution of occupied electronic states in the electrode [5]. In this framework, the standard ET rate constant ((k^0)) is intimately connected to the reorganization energy.

The conventional understanding posited that the reorganization energy arises largely from nuclear reconfigurations in the electrolyte phase, typically those of the solvent and, in some cases, the redox molecule itself [5]. The electrode's electronic density of states (DOS) was believed to serve exclusively to dictate the number of thermally accessible channels for ET. This perspective has been successfully applied to explain ET behavior across various material systems, including carbon-based electrodes and noble metals.

The Electronic Structure Paradigm

Recent advances have revealed a more complex picture, demonstrating that the electrode's electronic structure directly influences the reorganization energy itself. Using atomically layered van der Waals heterostructures to precisely tune the DOS of graphene, researchers have measured heterogeneous outer-sphere electrochemical ET kinetics and observed strong modulation in reorganization energy associated with image potential localization in the electrode [5].

The Thomas-Fermi screening length ((ℓ_{TF})), which quantifies the lengthscale over which charges are screened in imperfect metals, scales inversely with DOS. Higher metallicity leads to sharper charge localization, whereas lower metallicity yields a more diffuse charge distribution [5]. This tunability offers a new avenue to investigate how electronic screening shapes interfacial ET. At low charge carrier densities—such as those found in many low-dimensional electrode materials and semiconductors—the reorganization energy penalty owing to the low electrode DOS can be of magnitude comparable to that arising in the solvent at a metallic electrode [5].

Table 1: Key Parameters Governing Electron Transfer Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in ET Kinetics | Experimental Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganization Energy | λ | Activation energy required for nuclear rearrangement during ET | Solvent selection, electrode distance, electronic structure tuning |

| Electronic Density of States | DOS | Determines number of accessible ET channels and influences λ through screening | Electrode material selection, doping, defect engineering |

| Standard ET Rate Constant | (k^0) | Quantitative measure of ET kinetics at formal potential | Measured via electrochemical techniques; depends on λ and DOS |

| Thomas-Fermi Screening Length | (ℓ_{TF}) | Lengthscale of charge screening in electrode; inversely proportional to DOS | Controlled via carrier density modulation in low-dimensional materials |

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating ET Kinetics

Advanced Electrochemical Techniques

Investigating electron transfer kinetics requires specialized electrochemical techniques capable of probing interfacial processes with high sensitivity and spatial resolution. Scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) operating in feedback mode has emerged as a powerful tool for quantifying ET rate constants while imaging electroactivity of redox probes [6]. This technique enables the measurement of standard ET kinetic rate constants ((k^0)) across diverse material families, with reported values typically ranging from 0.01–0.1 cm/s via SECM, which are often higher than ensemble-averaged methods (0.001–0.01 cm/s) due to the ability to probe localized active sites [6].

Scanning electrochemical cell microscopy (SECCM) represents another advanced approach, enabling nanoscale electrochemical measurements by positioning an electrolyte-filled nanopipette over the sample and forming a confined electrochemical cell upon meniscus contact [5]. This technique has been particularly valuable for studying ET kinetics across two-dimensional materials and van der Waals heterostructures with controlled electronic properties.

Protocol: Measuring ET Kinetics with SECM

Electrode Preparation: Fabricate or obtain the electrode material of interest. For graphene-family nanomaterials, this may involve chemical vapor deposition, mechanical exfoliation, or laser-induced transformation [6].

Redox Probe Selection: Prepare solutions containing appropriate outer-sphere redox couples. Common probes include potassium hexacyanoferrate(III/IV) [Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻] or ferrocene methanol [Fc⁰/Fc⁺] at concentrations of 1-5 mM in supporting electrolyte [6].

SECM Configuration: Set up the SECM in feedback mode with an ultramicroelectrode (UME) tip positioned near the substrate surface in solution. Maintain constant tip-substrate distance during measurements.

Feedback Measurement: Record the tip current while scanning across the substrate surface. The current response depends on the substrate's ability to regenerate the redox species, directly reflecting local ET kinetics.

Data Analysis: Fit the approach curves to theoretical models to extract quantitative ET rate constants ((k^0)). Compare values across different material regions and defects.

Validation: Correlate electrochemical activity with structural characterization techniques (Raman spectroscopy, SEM) to establish structure-activity relationships [6].

Protocol: Investigating DOS-Dependent ET Kinetics

Heterostructure Fabrication: Assemble van der Waals heterostructures using mechanical transfer techniques. For DOS tuning, combine monolayer graphene with solid-state dopant layers (e.g., RuCl₃ for hole doping, WSe₂ for electron doping) separated by hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) spacers of varying thickness (3-120 nm) [5].

Device Characterization: Employ Raman spectroscopy and Hall measurements to quantify doping levels as a function of hBN thickness. Monitor G-peak shifts to confirm successful doping [5].

Electrochemical Measurement: Use SECCM with quartz nanopipettes (600-800 nm diameter) containing 2 mM hexaammineruthenium(III) chloride and 100 mM KCl supporting electrolyte.

Kinetic Analysis: Record steady-state cyclic voltammograms of the [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ couple at the basal plane of heterostructures. Determine half-wave potential (E₁/₂) shifts and extract standard rate constants (k⁰) through finite-element simulations using software such as COMSOL Multiphysics [5].

Model Fitting: Compare experimental results with theoretical predictions, accounting for both the number of thermally accessible ET channels and the DOS-dependent reorganization energy.

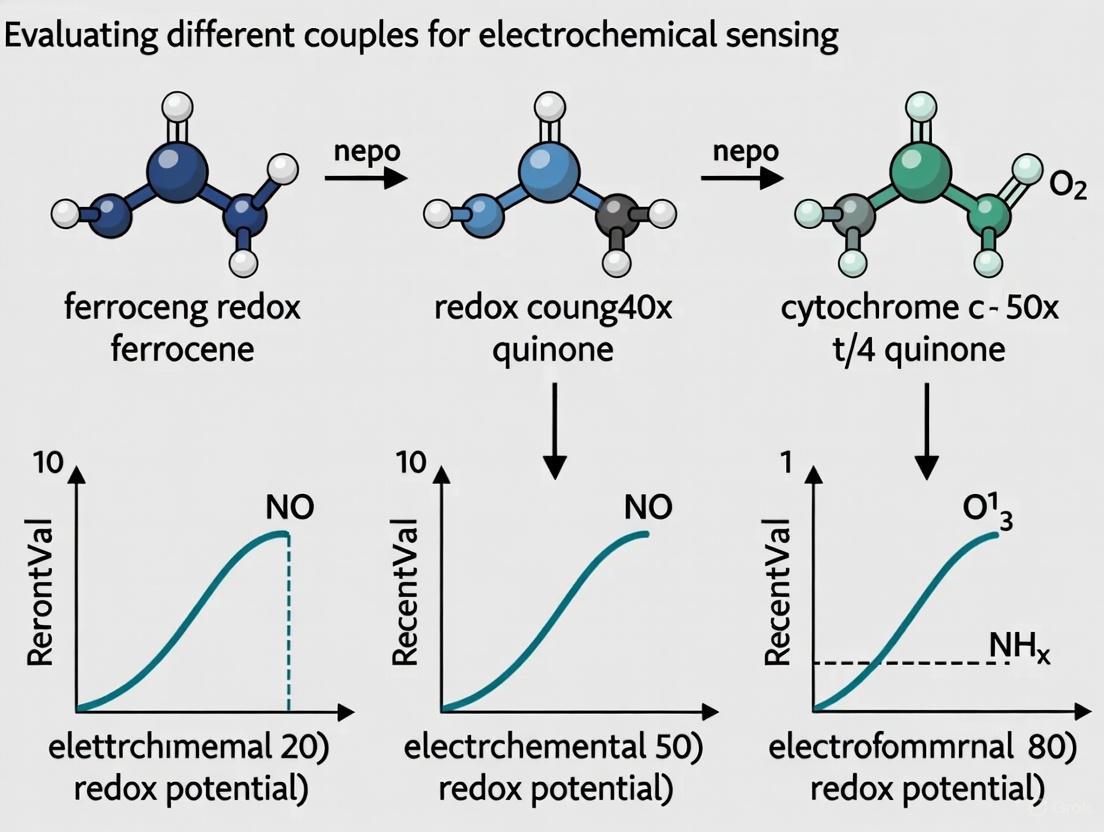

Comparative Analysis of Electrode Materials and Redox Couples

Graphene-Family Nanomaterials

Graphene-family nanomaterials (GFNs) present a complex interplay between outer-sphere and inner-sphere electron transfer pathways, fundamentally governed by the coordination sphere's charge exchange capabilities [6]. The enhanced ET kinetics observed in certain GFNs compared to traditional graphite electrodes has been attributed to several factors:

- Point-like topological defects in the basal plane with number density of ~10¹²/cm² significantly enhance electroactivity [6].

- Oxygen functional groups (C/O ratio: 4:1-12:1) and nitrogen doping create active sites for ET [6].

- Edge plane hydrogen-bonding sites (density: 0.1-1.0 μm⁻¹) contribute to improved kinetics, particularly for certain redox couples [6].

- Quantum capacitance effects and available density of states near the Fermi level (-0.2 to +0.2 eV) play crucial roles in modulating ET rates [6].

Laser-induced graphene (LIPG) represents a particularly promising GFN variant, containing pentagon-heptagon coordinated rings as topological structures (Stone-Wales defects) that create a three-dimensional interconnected network of multilayer graphene sheets with enhanced electrochemical activity [6].

Redox Couples in Electrochemical Sensing

The selection of appropriate redox couples is critical for designing effective electrochemical sensors. Different couples exhibit distinct ET behaviors depending on their interaction with the electrode surface and reorganization energies.

Table 2: Comparison of Redox Couples for Electrochemical Sensing Applications

| Redox Couple | ET Mechanism | Typical k⁰ Range (cm/s) | Sensing Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | Primarily outer-sphere | 0.001-0.1 [6] | General purpose biosensing | Well-defined electrochemistry, fast kinetics | Sensitivity to surface defects and oxygen |

| [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ | Outer-sphere | ~0.01-0.1 [5] | Fundamental ET studies, DOS investigations | Minimal specific adsorption, ideal for kinetics studies | Limited applications in specific sensing |

| Ferrocene Methanol (Fc⁰/Fc⁺) | Outer-sphere | 0.01-0.1 [6] | Biosensor redox mediator | pH-independent electrochemistry, stable derivatives | Potential surface adsorption issues |

| Hydroquinone/Benzoquinone | Mixed inner/outer-sphere | Varies with pH | Environmental monitoring, multiplexed sensing [7] | pH-dependent electrochemistry enables multiplexing | Complex reaction mechanisms, polymerization risks |

| H₂O₂ | Catalytic (enzyme-free) | Dependent on catalyst [8] | Environmental, biomedical sensing | Enzyme-free detection possible, clinically relevant | Often requires catalytic electrodes for low overpotential |

Emerging Electrode Materials and Their Performance

Recent research has explored numerous advanced electrode materials beyond conventional GFNs, each offering distinct advantages for specific sensing applications:

Bimetallic Phosphides: Materials like NiFeP nanointerfaces synthesized via two-pot hydrothermal methods followed by high-temperature phosphorization have demonstrated exceptional performance for enzyme-free H₂O₂ detection. These systems leverage reversible redox couples (Ni²⁺/Ni³⁺ and Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺) at the electrode surface, achieving remarkable sensitivity and low detection limits through synergistic effects between bimetallic components and phosphorus atoms [8].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Integrated with carbon dots (CDs) on electrode surfaces, MIPs/CDs systems offer enhanced selectivity for specific analytes like 3-monochloropropane-1,2-diol (3-MCPD) in food safety applications. The incorporation of CDs significantly improves electrochemical response and recognition capability [9] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ET Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexaammineruthenium(III) chloride | Outer-sphere redox probe for fundamental ET studies | Investigating DOS-dependent reorganization energy in 2D materials [5] | Minimal specific adsorption, ideal kinetics studies |

| Potassium hexacyanoferrate(III) | Standard outer-sphere redox couple | Benchmarking electrode activity across GFNs [6] | Sensitive to surface defects and oxygen content |

| Ferrocene methanol | Outer-sphere redox mediator with pH-independent electrochemistry | Biosensor development and fundamental ET studies [6] | Well-defined single-electron transfer |

| Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) | insulating spacer in van der Waals heterostructures | Precisely tuning DOS in graphene via electrostatic doping [5] | Thickness control critical for doping efficiency |

| Chitosan-based molecularly imprinted polymers | Selective recognition elements in sensors | Specific detection of 3-MCPD in food samples [9] [10] | Combined with carbon dots for enhanced response |

| NiFeP nanosheets | Enzyme-free catalytic interface | Sensitive H₂O₂ detection without biological components [8] | Leverages reversible metal redox couples |

| Laser-induced graphene (LIPG) | 3D porous electrode material with enhanced activity | Creating flexible, high-surface area sensors [6] | Contains inherent topological defects |

The field of electron transfer kinetics in electrolytes continues to evolve, with recent paradigm-shifting discoveries highlighting the crucial role of electrode electronic structure in governing reorganization energy—a departure from traditional views that focused exclusively on electrolyte contributions. This fundamental understanding enables more rational design of electrochemical sensing platforms through strategic selection of electrode materials, redox couples, and experimental configurations.

The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates that optimal sensor performance emerges from synergistic matching between electrode properties (DOS, defect structure, quantum capacitance) and redox probe characteristics (reorganization energy, inner-vs-outer-sphere mechanism). Advanced materials such as bimetallic phosphides, doped graphene variants, and molecularly imprinted polymers hybridized with carbon nanomaterials offer promising pathways toward next-generation sensors with enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, and application-specific functionality.

As the field progresses, integration of artificial intelligence for data analysis [7], development of multi-functional heterostructures with precisely tuned electronic properties [5], and implementation of advanced local probe techniques [6] will further advance our understanding and manipulation of electron transfer kinetics for sensing applications.

In the field of electrochemical sensing, redox probes are fundamental tools for characterizing electrode interfaces, understanding electron transfer kinetics, and developing new biosensing platforms. Among them, the ferri/ferrocyanide couple, [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻, stands as a ubiquitous benchmark due to its well-defined electrochemistry and historical prevalence. However, its performance is not universal and can be significantly influenced by electrode material, surface chemistry, and the experimental environment. This guide provides an objective comparison of the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe against other common alternatives, presenting key experimental data and methodologies to inform researchers and development professionals in selecting the appropriate probe for their specific applications.

Performance Comparison of Common Redox Probes

The selection of a redox probe is a critical step in sensor design, as each couple possesses distinct electrochemical behaviors and sensitivities to different interfacial properties. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of several conventional redox probes.

Table 1: Comparative properties of conventional redox probes used in electrochemical sensing.

| Redox Probe | Typical Formal Potential (V vs. Ag/AgCl) | Electron Transfer Kinetics | Surface Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | ~+0.22 V [4] | Quasi-reversible, sensitive to surface state [11] | High; strongly dependent on surface chemistry and carbon electrode microstructure [11] | Inexpensive, well-established protocols [11] | Surface-sensitive nature can lead to misinterpretations; does not behave as an ideal outer-sphere probe [11] |

| [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ | ~-0.16 V [12] | Near-ideal, fast, outer-sphere [11] | Low; largely insensitive to electrode roughness, ideal for assessing intrinsic electron transfer rates [11] | Valuable for assessing true electron transfer kinetics [11] | High cost can be prohibitive [11] |

| Ferrocene (Fc/Fc⁺) | ~+0.32 V (varies with derivatives) | Generally fast and reversible | Moderate; dependent on monolayer formation and surface modification | Excellent mediator for enzyme-based biosensors [13] | Poor stability in long-term storage and complex matrices like blood serum [14] |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | ~-0.27 V [14] | Reversible | Moderate; sensitive to conformational changes in DNA probes | High stability in complex media and to repeated interrogation cycles [14] | Requires careful conjugation chemistry for labeling [14] |

The performance of these probes can be further quantified through specific electrochemical parameters obtained under standardized conditions, as shown in the following experimental data.

Table 2: Experimental kinetic parameters for redox probes in different media (data obtained at planar Au/Pt electrodes).

| Redox Probe | Experimental Condition | Diffusion Coefficient (cm²/s) | Electron Transfer Rate Constant, k⁰ (cm/s) | Charge Transfer Resistance, Rct (Ω) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | 0.1 M NaCl, conventional aqueous medium [4] | ~6.5 × 10⁻⁶ | ~5.7 × 10⁻³ | - |

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | Artificial sweat bio-mimic [4] | ~4.7 × 10⁻⁶ | ~3.1 × 10⁻³ | ~540 |

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | Artificial saliva bio-mimic [4] | ~5.2 × 10⁻⁶ | ~4.5 × 10⁻³ | ~420 |

| [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ | Temperature range 5-60°C [12] | - | Activation Energy (Eₐ): ~3.35 kJ/mol | - |

| [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ | 1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) [12] | - | - | - |

| Methylene Blue | DNA-based sensor on Au electrode [14] | - | - | - |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Characterizing Electrode Surface Area and Kinetics

A common application of the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ probe is the electrochemical characterization of electrode surfaces.

- Objective: To assess the electron transfer kinetics and estimate the electroactive area of a newly fabricated or modified electrode.

- Probe Solution: 1-5 mM Potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) and/or potassium ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) in a supporting electrolyte such as 0.1 M KCl or 1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) [12] [4].

- Methodology - Cyclic Voltammetry (CV):

- Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system with the target electrode as the working electrode.

- Parameters: Scan potential from -0.4 V to +0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s [4]. Repeat at multiple scan rates (e.g., 25, 50, 100, 200 mV/s).

- Data Analysis:

- Methodology - Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS):

- Parameters: Apply a DC potential at the formal potential of the probe (~0.22 V) with a small AC amplitude of 20 mV, scanning frequencies from 100 kHz to 10 Hz [12].

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting Nyquist plot to a Randles equivalent circuit to extract the charge transfer resistance (Rct), which is inversely related to the electron transfer rate [12] [4].

Assessing Sensor Performance in Bio-Mimicking Media

Evaluating probes in biologically relevant conditions is crucial for diagnostic sensor development.

- Objective: To understand electron transfer behavior of [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in non-conventional, complex electrolytes like artificial sweat and saliva [4].

- Probe Solution:

- Artificial Sweat Bio-mimic: Prepare according to standard recipes, containing salts like NaCl, urea, and lactic acid.

- Artificial Saliva Bio-mimic: Contains inorganic salts and organic compounds like mucin.

- Add 1 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ and 0.1 M NaCl as supporting electrolyte to these bio-mimics [4].

- Methodology:

- Perform CV and EIS as described in section 3.1 on Au and Pt disk electrodes.

- Compare the calculated diffusion coefficients and charge transfer resistances with those obtained in a conventional aqueous electrolyte [4].

- Key Findings: Electron transfer for [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ remains diffusion-controlled in these bio-mimics, though kinetic parameters like the rate constant are reduced due to the complex matrix, highlighting the need for validation in application-specific media [4].

Determining Temperature-Dependent Thermodynamic Parameters

Automated systems can efficiently extract key thermodynamic properties.

- Objective: To determine the activation energy (Eₐ) and thermogalvanic coefficient (α) of a redox couple [12].

- Probe Solution: 50 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻ in 1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) [12].

- Methodology:

- Automated Setup: Utilize a temperature-controlled electrochemical cell with a water jacket, a heater, and a programmable potentiostat.

- EIS for Activation Energy:

- Collect EIS spectra across a temperature range (e.g., 5°C to 60°C in 1°C increments).

- Extract Rct from each Nyquist plot and calculate the exchange current density (i₀).

- Plot ln(i₀) versus 1/T; the slope of the linear fit gives Eₐ via the Arrhenius equation [12].

- CV for Thermogalvanic Coefficient:

- Record cyclic voltammograms across the same temperature range.

- Plot the formal potential (E₁/₂) versus temperature. The slope (ΔE/ΔT) is the thermogalvanic coefficient, α [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for experiments with the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox probe.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) | Oxidized form of the redox couple. | Commonly used in equimolar mixtures with ferrocyanide or alone. |

| Potassium Ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | Reduced form of the redox couple. | - |

| Supporting Electrolyte (KCl, Phosphate Buffer) | Minimizes solution resistance and suppresses migration current. | High concentration (e.g., 0.1 M - 1 M) is crucial [12] [4]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 | Biologically relevant buffer for sensor testing. | - |

| Artificial Sweat & Saliva Formulations | Bio-mimicking media for diagnostic sensor development [4]. | - |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized platforms for decentralized sensing [11]. | - |

| Ruthenium Hexaammine Chloride ([Ru(NH₃)₆]Cl₃) | Outer-sphere redox probe for comparative kinetics studies [11] [12]. | More expensive but less surface-sensitive. |

Experimental Workflow and Probe Selection Logic

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting and applying a conventional redox probe in sensor characterization, highlighting the decision points where the limitations of [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ might necessitate an alternative.

The [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ redox couple remains a cornerstone of electrochemical research due to its cost-effectiveness and the depth of historical data available for comparison. Its behavior is a sensitive reporter of surface cleanliness and modification. However, this very sensitivity is its primary drawback, as it often deviates from ideal, outer-sphere behavior, particularly on carbon-based and rough electrodes. For researchers requiring an unambiguous measure of electron transfer kinetics, [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺ is superior, despite its cost. For applications in complex biological fluids or those requiring a stable, covalently attached label, methylene blue offers significant advantages over alternatives like ferrocene. Therefore, the [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ benchmark should not be applied dogmatically but rather as one tool in a suite, with its results interpreted in the context of its known limitations and validated with more specific probes when necessary.

Endogenous redox molecules are crucial components in cellular metabolism and signaling, serving as key charge carriers and mediators in numerous physiological and pathological processes. The electrochemical sensing of these molecules—particularly NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and phenazines—provides powerful tools for deciphering cellular communication, oxidative stress, and energy metabolism. This guide objectively compares the electrochemical sensing performance of these three redox couples, framing the analysis within broader research efforts to develop efficient biosensors and bioelectronic devices. Accurate detection of these molecules is paramount for clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, and understanding fundamental biological processes, as these analytes are involved in everything from cellular energy regulation to bacterial communication and oxidative stress responses [15] [16] [1].

Electrochemical Performance Comparison

The electrochemical characteristics of NADH, H₂O₂, and phenazines differ significantly, influencing sensor design, required overpotentials, and overall detection performance. The table below summarizes key quantitative sensing data for these molecules as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Comparative Electrochemical Sensing Performance for NADH, H₂O₂, and Phenazines

| Redox Molecule | Sensor Material / Configuration | Linear Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sensitivity | Key Sensor Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH | Poly(phenosafranin)-modified carbon electrode [16] | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Mediated electron transfer; lowers overpotential; minimizes fouling |

| Palladium nanoparticle-decorated laser-induced graphene (nanoPd@LIG) [17] | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Enhanced current response; lowered peak potential | |

| H₂O₂ | Cobalt Phthalocyanine-modified Carbon Nanopipette (CoPcS-CNP) [15] | 10 μM to 1500 μM | 1.7 μM | Information missing | High selectivity/stability in cells; single-cell analysis |

| NiO Octahedron/3D Graphene Hydrogel (3DGH/NiO25) [18] | 10 μM to 33.58 mM | 5.3 μM | 117.26 μA mM⁻¹ cm⁻² | Non-enzymatic; good selectivity & reproducibility | |

| Ag-doped CeO₂/Ag₂O-modified GCE [19] | 1x10⁻⁸ M to 0.5x10⁻³ M | 6.34 μM | 2.728 μA cm⁻² μM⁻¹ | High electrocatalytic activity; broad linear range | |

| Phenazines | Phenazine-16/GOx-based Glucose Sensor [20] | 1.00 mM to 32.49 mM (glucose) | Information missing | Information missing | High selectivity vs. interferents; fast response (5 s) |

| Graphene-modified electrodes [1] | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Favourable π-π stacking enhances measurement |

Table 2: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Properties of Endogenous Redox Couples

| Redox Couple | Formal Potential (E°') vs. SCE, pH 7 | Detection Overpotential at Bare Electrodes | Primary Sensing Challenges | Common Mediators/Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADH/NAD⁺ | -0.557 V [16] | High overpotential required [21] [16] | Electrode fouling, side reactions, formation of inactive NAD⁺ [16] | Phenothiazines, phenoxazines, quinones, polyazines [21] [16] |

| H₂O₂ | Information missing | High overpotential for direct oxidation/reduction [15] | Selectivity in complex physiological environments [15] | Pt, Prussian blue, enzymes, CoPc, NiO, metal oxides [15] [18] [19] |

| Phenazines | Low redox potentials (e.g., Phenosafranin: -0.458 V vs. NHE) [16] | Information missing | Low solubility in water for pristine phenazine [20] | Structural derivatization with water-soluble moieties [20] |

Experimental Protocols for Electrochemical Sensing

Sensor Fabrication and Modification Protocols

Protocol A: Modification with Redox Mediators via Adsorption (e.g., Phenothiazines for NADH)

- Electrode Preparation: Polish spectrographic graphite electrodes (e.g., 3 mm diameter) with alumina slurry and rinse thoroughly with deionized water [21].

- Mediator Adsorption: Immerse the electrode in a 1.0 x 10⁻³ M solution of the phenothiazine derivative (e.g., in absolute ethanol) for a set time (e.g., 20 minutes) to allow for physical adsorption [21].

- Final Preparation: Rinse the modified electrode gently with the solvent to remove loosely adsorbed molecules and dry at room temperature before use [21].

Protocol B: Fabrication of Nanocomposite-Modified Electrodes (e.g., for H₂O₂)

- Nanomaterial Synthesis: Prepare the catalytic nanomaterial. For example, synthesize NiO octahedrons using a mesoporous silica SBA-15 hard template, followed by calcination and template removal with NaOH [18].

- Composite Formation: Disperse graphene oxide (GO) in deionized water. Add a precise amount of the nanomaterial (e.g., 25 wt% NiO) and sonicate to achieve a homogeneous mixture [18].

- Hydrothermal Assembly: Transfer the mixture to a Teflon-lined autoclave and maintain at 180°C for 12 hours to form a 3D hydrogel composite [18].

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast a measured volume (e.g., 5-10 μL) of the nanocomposite suspension onto a polished glassy carbon electrode (GCE) and allow it to dry under ambient conditions [18] [19].

Electrochemical Measurement and Characterization Protocols

Protocol C: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for Sensor Characterization

- Experimental Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system with the modified electrode as the working electrode, a platinum wire/counter electrode, and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or SCE) [21] [16].

- Parameters: Perform CV scans in a blank buffer solution (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) and subsequently in the same solution containing the target analyte (NADH, H₂O₂) [21] [16].

- Data Analysis: Determine the formal potential from the midpoint of the anodic and cathodic peaks. Observe the increase in anodic current (for oxidation) or cathodic current (for reduction) upon analyte addition as evidence of electrocatalytic activity [21] [16].

Protocol D: Amperometric Detection for Biosensing Applications

- Setup: Use a stirred solution in a three-electrode cell to ensure consistent mass transport [18] [19].

- Potential Application: Apply a constant optimal potential (determined from CV experiments) to the working electrode [18] [19].

- Calibration: Record the steady-state current response upon successive additions of the analyte standard solution. Plot the current versus concentration to establish a calibration curve for determining sensitivity and linear range [18] [19].

- Interference Testing: Test the sensor's response to common interfering species (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid, dopamine, glucose) to establish selectivity [18] [20] [19].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core biological roles of these redox molecules and a generalized workflow for their electrochemical detection.

Diagram 1: Redox molecule biological roles and detection principle.

Diagram 2: General experimental workflow for sensor development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful electrochemical sensing of endogenous redox molecules relies on specialized materials and reagents. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Redox Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Provides conductive surface for electron transfer; influences sensitivity and overpotential. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE), Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCE) [22] |

| Redox Mediators | Shuttles electrons between biomolecule and electrode; lowers overpotential, minimizes fouling. | Phenothiazines (e.g., Toluidine Blue), Phenoxazines, Quinones, Ferrocene derivatives [21] [16] [20] |

| Nanostructured Catalysts | Enhates electrocatalytic activity, increases active surface area, improves sensitivity and selectivity. | Cobalt Phthalocyanine (CoPc), Nickel Oxide (NiO), Silver/Cerium Oxide (Ag-CeO₂/Ag₂O), Palladium Nanoparticles (PdNPs) [15] [18] [17] |

| Supporting Matrices | Provides high surface area support for catalysts/mediators, enhances electron transfer and stability. | 3D Graphene Hydrogel, Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs), Graphitic Carbon Nitride (g-C₃N₄) [23] [18] |

| Enzymes (for Biosensors) | Provides biological recognition and specificity for the target analyte. | Glucose Oxidase (GOx), Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH), Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) [20] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintains stable pH for consistent electrochemical measurements and biomolecule activity. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) [18] [19] |

The comparative analysis of NADH, H₂O₂, and phenazines reveals distinct electrochemical sensing landscapes for each redox couple. NADH sensing is dominated by the challenge of high overpotential and electrode fouling, effectively addressed using mediator-modified electrodes. H₂O₂ detection showcases advanced non-enzymatic platforms utilizing nanostructured metal oxides and composites, achieving wide linear ranges and high sensitivities crucial for physiological and environmental monitoring. Phenazine-based sensing leverages their low redox potentials for selective detection, with recent advances focusing on rational molecular design to improve water solubility and mediator efficiency. The choice of the optimal sensing strategy depends fundamentally on the specific application, required sensitivity, and the complexity of the sample matrix. Future directions in this field point toward the increased use of hybrid nanomaterials, sophisticated computational design of mediators, and the integration of these sensors into closed-loop systems for real-time biological monitoring and control [20] [17] [1].

The Framework of Molecular Communication Theory in Biomolecular Sensing

Molecular communication (MC) is an emerging interdisciplinary paradigm that utilizes molecules as carriers of information, mimicking communication mechanisms found in biological systems [24] [25]. Unlike traditional electromagnetic-based communication, MC employs biochemical signals to enable communication between biological and artificially created nano- or microscale entities, such as cells, sensors, and biohybrid devices [24]. This framework is particularly relevant for biomolecular sensing applications where traditional electronic communication is inefficient, unsafe, or infeasible—including intrabody biosensing, smart drug delivery systems, and lab-on-a-chip devices [25] [26]. The fundamental principle of MC involves a sender generating information molecules, encoding information onto them, and emitting them into the propagation environment. These molecules are then transported to a receiver, which biochemically reacts to the molecules, effectively decoding the information [24]. This process forms the basis for developing sophisticated biomolecular sensors that can operate in physiological environments with high biocompatibility and minimal invasiveness.

Within the broader thesis of evaluating redox couples for electrochemical sensing research, MC theory provides a structured framework for understanding how molecular information is transmitted, received, and processed in biological contexts. By applying communication theory to molecular interactions, researchers can design more efficient biosensors, optimize signal-to-noise ratios, and develop novel modulation techniques for detecting biomarkers in complex biological fluids [1] [25]. The integration of redox-based electrochemical sensing with MC theory is particularly powerful, as redox reactions naturally mediate communication within biological systems and can be effectively coupled with electronic readouts [1]. This synergy enables the creation of bio-electronic interfaces that facilitate bidirectional information transfer between biology and electronics, opening new possibilities for medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and therapeutic applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Molecular Communication Systems

The architecture of a molecular communication system can be abstracted into core components analogous to traditional communication systems: transmitter, channel, and receiver [24] [27]. Table 1 summarizes the key components and functions of a molecular communication system for biomolecular sensing.

Table 1: Core Components of a Molecular Communication System for Biomolecular Sensing

| Component | Function in Biomolecular Sensing | Biological/Technical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Transmitter | Encodes information into molecular properties and releases signal molecules | Engineered cells, synthetic vesicles, microfluidic pumps [24] [26] |

| Information Molecules | Carry encoded information through physical/chemical properties | Hormones, neurotransmitters, DNA strands, redox probes (methylene blue, ferrocene) [24] [14] |

| Propagation Channel | Transports information molecules from transmitter to receiver | Diffusion-based transport, flow-based microfluidic systems, active transport using motor proteins [24] [27] |

| Receiver | Detects incoming molecules and decodes information through biochemical reactions | Cell surface receptors, engineered biosensors, electrochemical electrodes [24] [1] |

| Signal Processing | Processes molecular signals to extract meaningful information | Biological circuits, chemical reaction networks, electronic algorithms [26] [27] |

Molecular communication systems employ various propagation mechanisms, with diffusion being the most fundamental. In diffusion-based propagation, molecules move randomly according to Brownian motion from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration [25]. This mechanism is particularly relevant for short-range communications in aqueous environments, such as intercellular signaling in biological systems. For longer-range or more directed transport, flow-based propagation (utilizing natural or artificial fluid flows) and active transport (employing motor proteins like kinesin along microtubule tracks) can be implemented [24] [27]. The choice of propagation mechanism significantly impacts key communication parameters including latency, data rate, and reliability, which must be carefully considered when designing biomolecular sensors for specific applications.

The following diagram illustrates the complete architecture of a molecular communication system for biomolecular sensing, integrating both biological and electronic components:

Molecular communication systems employ various modulation techniques to encode information onto molecular signals. Concentration-based modulation encodes information in the concentration levels of messenger molecules, while molecular-type-based modulation utilizes different types of molecules to represent different symbols [25]. More advanced techniques include molecular-ratio-based modulation, which represents information through specific ratios of isomer molecules [25]. These modulation schemes offer different trade-offs in terms of data rate, complexity, and reliability, allowing researchers to select appropriate encoding strategies based on specific sensing requirements and environmental constraints.

Electrochemical Sensing Redox Couples: Experimental Comparison

Redox couples serve as fundamental signaling elements in electrochemical biomolecular sensing, facilitating the conversion of molecular recognition events into measurable electrical signals [14] [1]. The performance of these redox probes significantly impacts sensor characteristics including sensitivity, stability, and operational requirements. Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of two commonly used redox couples in electrochemical biosensing: methylene blue and ferrocene.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Redox Couples in Electrochemical Biosensing

| Parameter | Methylene Blue (MB) | Ferrocene (Fc) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Gain | High (∼80% signal suppression upon target binding) [14] | Slightly higher than MB [14] | E-DNA sensor with 32-base DNA probe [14] |

| Target Affinity | High | Slightly improved over MB [14] | Measurement in buffer solution with 1µM target DNA [14] |

| Stability to Long-term Storage | High (minimal signal degradation over 180 hours) [14] | Significant signal degradation [14] | Storage in HEPES/NaClO4 buffer at room temperature [14] |

| Stability to Repeated Interrogation | Maintains performance through multiple SWV scans [14] | Rapid signal deterioration [14] | 15 successive square wave voltammetry scans [14] |

| Performance in Complex Media | Maintains functionality in blood serum [14] | Fails due to protein adsorption [14] | Measurements in 20% fetal calf serum [14] |

| Redox Potential | -0.35V to 0.35V (vs. Ag/AgCl) [28] | -0.26V to 0.24V (vs. Ag/AgCl) [28] | Cyclic voltammetry in buffer solution [28] |

The selection of an appropriate redox couple extends beyond these common probes. The ferrocyanide/ferricyanide couple ([Fe(CN)6]3−/4−) serves as a standard redox probe in fundamental studies and method validation [28] [4]. Recent research has investigated its electron transfer characteristics in biologically relevant environments, including artificially simulated human sweat and saliva [4]. These studies reveal that the electron transfer reaction of [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− remains diffusion-controlled on both gold and platinum electrodes in these bio-mimicking solutions, though charge transfer resistance increases significantly in complex matrices [4]. This understanding is crucial for developing wearable sensors and non-invasive diagnostic devices that operate using unconventional bio-fluids.

The experimental workflow for evaluating redox couples in electrochemical biosensing typically involves electrode modification, electrochemical measurement, and data analysis. The following diagram illustrates a standardized protocol for fabricating and testing electrochemical DNA (E-DNA) sensors:

Advanced Methodologies in Molecular Communication Sensing

Microfluidic Platforms for Chemical Signal Processing

Recent advancements in molecular communication sensing include the development of liquid-based microfluidic platforms that perform signal processing directly in the molecular domain, eliminating the need for electronic conversions [26]. These systems utilize precisely designed chemical reactions and microfluidic geometry to implement essential communication functions including pulse shaping, thresholding, and amplification. In one demonstrated platform, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) serves as the information molecule, with hydrochloric acid (HCl) acting as a signal suppressor at the transmitter to shape the emitted concentration signals [26]. At the receiver, thresholding reactions remove noise and intersymbol interference, while amplification reactions enhance detectable signals. Such systems have successfully achieved reliable text message transmission over distances up to 25 meters using only chemical reactions for signal processing, demonstrating bit error rates below practical thresholds [26]. This approach is particularly valuable for applications requiring complete biocompatibility, such as implantable sensors and targeted drug delivery systems.

Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Signal Processing

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with electrochemical sensing addresses significant challenges in molecular communication, particularly the resolution of overlapping signals from multiple redox probes with similar electrochemical potentials [28]. Machine learning algorithms, including deep learning networks, can process complex voltammetric data to distinguish subtle patterns imperceptible to conventional analytical methods. In one recent study, AI-assisted analysis enabled simultaneous detection of multiple quinone-family compounds (hydroquinone, benzoquinone, and catechol) along with ferrocyanide as a reference redox probe in both deionized and tap water [28]. The AI model achieved detection limits as low as 0.8μM for individual analytes in mixtures where traditional cyclic voltammetry showed only two discernible peaks despite four distinct redox species being present [28]. This capability is crucial for complex biomedical and environmental sensing applications where multiple biomarkers must be detected simultaneously in complex matrices.

Hybrid Bio-Electronic Frameworks

Hybrid approaches that combine biological sensing elements with electronic processing offer a promising middle ground for molecular communication systems [27]. These frameworks leverage the exquisite sensitivity and specificity of biological sensors while offloading complex computation to electronic systems. Optogenetics—using light to control biological processes—provides a powerful interface in such systems [27]. For instance, engineered microbial biosensors can detect target molecules with high specificity, while light pulses controlled by electronic systems activate or deactivate these sensors as needed. This approach reduces the burden on biological components to implement complex communication algorithms, overcoming significant limitations of purely biological molecular communication networks, including slow processing speeds and limited computational capabilities [27]. The hybrid framework maintains biocompatibility for sensing while leveraging the processing power and communication infrastructure of traditional electronics.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of molecular communication-based sensing requires specific reagents and materials tailored to the experimental approach. Table 3 catalogizes key research reagent solutions essential for working in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Communication Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Probes | Signal transduction in electrochemical sensors | Methylene blue, Ferrocene, Ferrocyanide/Ferricyanide [14] [28] |

| Functionalized DNA Probes | Target recognition elements in biosensors | Thiol-modified at 5' terminus, amine-modified at 3' terminus for redox label conjugation [14] |

| Vesicle-Based Interfaces | Compartmentalization and transport of information molecules | Liposomes with diameter 50nm-50μm; can be embedded with connexins for gap junction communication [24] |

| Microfluidic Components | Miniaturized propagation channels and reaction chambers | Configurable tubing, screen-printed electrodes (graphite working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference) [28] [26] |

| Bio-Mimicking Solutions | Realistic testing media for sensor validation | Artificially simulated sweat and saliva with characteristic ionic compositions [4] |

| Motor Proteins & Filaments | Active transport systems for molecular communication | Kinesin and microtubule systems for directed cargo transport [24] |

Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) have emerged as particularly valuable tools in molecular communication sensing due to their disposability, reproducibility, and miniaturization capabilities [28]. A typical SPE configuration includes a graphite ink working electrode, a graphite ink counter electrode, and a silver/silver chloride reference electrode, with an active surface area of approximately 0.07 cm² [28]. These electrodes facilitate rapid testing of redox probes in various media and can be mass-produced at low cost, making them ideal for both laboratory research and potential commercial biosensor applications.

Enzyme-based recognition elements serve as critical communication filters in molecular communication systems, providing specificity for target analytes while often amplifying signals through catalytic activity [1]. These biological components can refine or transform molecular messages by converting substrates in a communication chain to new message carriers, representing a fundamental form of information processing within molecular communication networks [1]. When selecting enzymes for sensing applications, researchers must consider factors including substrate specificity, reaction kinetics, stability under operational conditions, and compatibility with the chosen transduction mechanism.

The framework of molecular communication theory provides a powerful paradigm for advancing biomolecular sensing capabilities, particularly when integrated with electrochemical sensing approaches utilizing optimized redox couples. As this field evolves, several promising research directions emerge. The development of standardized molecular communication modules that can be seamlessly integrated to create complex sensing networks represents a significant challenge and opportunity. Additionally, the creation of robust theoretical models that accurately predict molecular communication performance in realistic biological environments will accelerate sensor design and optimization [27].

Future advancements will likely focus on increasing the complexity of information that can be transmitted through molecular channels, potentially incorporating multiple orthogonal redox couples that can operate simultaneously without interference. The integration of synthetic biology tools with electrochemical sensing may enable the creation of bio-hybrid systems that leverage engineered cellular components for sophisticated molecular recognition and signal processing tasks [27]. As these technologies mature, molecular communication-based sensors are poised to transform applications ranging from point-of-care diagnostics to environmental monitoring, ultimately enabling communication with biological systems at their native molecular scale.

Electrochemical Techniques and Biosensor Applications in Biomedicine

Electroanalytical techniques are indispensable in modern chemical analysis, offering powerful tools for quantifying analytes, studying reaction mechanisms, and developing sensing platforms. This guide objectively compares the performance of Voltammetry, Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), Amperometry, and Potentiometry, framed within the context of evaluating redox couples for electrochemical sensing research. The comparison draws on experimental data and established methodologies to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate technique for their specific applications.

Electroanalytical methods are a class of techniques that study an analyte by measuring the potential (volts) and/or current (amperes) in an electrochemical cell containing the analyte [29]. These methods are broadly categorized based on the electrical property measured and the control parameters. The fundamental setup for most quantitative electrochemical analyses involves a three-electrode system: a Working Electrode where the redox reaction occurs, a Reference Electrode that provides a stable, known potential, and a Counter Electrode that completes the circuit [30]. The relationship between chemical and electrical properties is governed by fundamental principles like the Nernst equation (cornerstone of potentiometry) and Faraday's laws of electrolysis (foundation for coulometry) [30].

For research on redox couples, such as the ferrocyanide/ferricyanide couple often used as a standard redox probe [7] [31], the choice of technique dictates the type of information that can be extracted, ranging from simple concentration measurements to intricate details of electron transfer kinetics and reaction mechanisms.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Techniques

The following table summarizes the core principles, key analytical parameters, and typical applications of the four electroanalytical techniques, providing a basis for their comparison.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Applications of Electroanalytical Techniques

| Technique | Measured Quantity & Principle | Key Outputs & Analytical Parameters | Primary Applications in Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Current as a function of applied potential [29] [30]. A varying potential program is applied to the working electrode. | Voltammogram (Current vs. Potential) [30]. Reduction Potential (qualitative), Peak Current (quantitative), Electrochemical Reactivity [29]. | Trace metal analysis [30], drug quantification [30], simultaneous detection of isomers (e.g., catechol & hydroquinone) [32], reaction mechanism studies [30]. |

| EIS | Impedance (real and imaginary components) in response to an oscillating potential across a frequency spectrum [31]. | Nyquist Plot (Imaginary vs. Real Impedance) [31]. Charge Transfer Resistance (Rct), interface properties, diffusion parameters. Interpretation often uses equivalent circuit models [31]. | Sensor interface characterization [31], studying binding events (e.g., antigen-antibody), monitoring film properties on electrode surfaces. |

| Amperometry | Current at a constant applied potential [29] [30]. | Current vs. Time [31]. Measured current is proportional to analyte concentration. | Glucose biosensors [30], detection of electroactive compounds in flow systems (e.g., HPLC) [30], real-time monitoring of reaction kinetics. |

| Potentiometry | Potential difference between two electrodes at zero current [29] [30]. | Potential (Volts) as a function of concentration/activity, governed by the Nernst equation [30]. | pH measurement [29] [30], ion-selective electrodes (Na+, K+, Ca2+, F-, Cl-) [30], potentiometric titrations [33]. |

A critical performance differentiator is the techniques' applicability in complex matrices. For instance, Voltammetry can be enhanced with machine learning to resolve overlapping signals from multiple analytes, such as differentiating hydroquinone, benzoquinone, and catechol in mixtures [7]. Advanced voltammetric techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) use pulsed potentials to minimize background current, achieving significantly higher sensitivity for trace analysis [30].

EIS excels in probing interfacial properties without being a destructive technique, making it ideal for studying the formation of layers on electrodes, such as in the development of immunosensors [31]. In contrast, Amperometry is a destructive technique because it consumes a small amount of analyte at the electrode surface, but it provides excellent continuous monitoring capabilities [29]. Potentiometry is a non-destructive, zero-current technique that affects the solution very little, ideal for prolonged monitoring of ionic activity [29] [30].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Voltammetric Detection of Dihydroxybenzene Isomers

This protocol is adapted from a study on sensing catechol (CC) and hydroquinone (HQ) at a polysorbate-modified carbon paste electrode (polysorbate/CPE) [32].

- Objective: To simultaneously resolve the overlapped oxidation signals of dihydroxy benzene isomers (CC and HQ) in tap water samples.

- Electrode System:

- Working Electrode: Polysorbate-modified carbon paste electrode (polysorbate/CPE).

- Reference Electrode: Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire [32].

- Electrode Fabrication:

- Prepare bare carbon paste electrode (bare/CPE) by homogeneously mixing graphite powder and silicone oil binder in a 70:30 ratio.

- Fill the uniform paste into the end of a Teflon hole and polish on smooth paper.

- Insert a copper wire for electrical contact.

- Drop-cast a specific amount of 25.0 mM polysorbate-80 solution onto the bare/CPE surface.

- Allow the electrode to stand for five minutes at room temperature.

- Rinse with distilled water to remove excess polysorbate-80 [32].

- Experimental Conditions:

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.2 M Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS), pH ~7.0 [32].

- Analytes: Standard solutions of catechol and hydroquinone.

- Technique: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) or Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV).

- Procedure:

- Place the polysorbate/CPE, SCE, and Pt wire into the PBS solution.

- Record a background voltammogram in the pure supporting electrolyte.

- Spike the solution with known concentrations of CC and HQ.

- Run the voltammetric scan (e.g., from 0.0 V to +0.6 V vs. SCE).

- Observe the resolved oxidation peaks for CC and HQ, which overlap at the bare/CPE.

- Measure the peak currents for quantification.

- Key Data & Outcome: The m/n value (ratio involving protons and electrons) obtained at the modified electrode was approximately 1, indicating an equal number of electron and proton transfer. The method achieved acceptable recovery results for CC and HQ in spiked tap water samples, demonstrating its analytical applicability [32].

Protocol 2: Multi-Electrode System for Antibiotic Identification using Machine Learning

This protocol is based on a study aimed at identifying multiple antibiotics in milk using a multi-electrode system and machine learning [31].

- Objective: To generate a complementary electrochemical dataset for the identification and classification of multiple antibiotic molecules in a complex matrix (milk).

- Electrode System:

- Working Electrodes: A system composed of Cu, Ni, and C working electrodes.

- Counter Electrode: A shared Cu counter electrode.

- Reference Electrode: (Implicitly used, type not specified in excerpt) [31].

- Experimental Conditions:

- Sample: Milk samples containing a single antibiotic molecule at five different concentrations. 15 different antibiotics were investigated.

- Technique: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

- Procedure:

- Immerse the multi-electrode system (Cu, Ni, C) in the milk sample.

- Perform a cyclic voltammetry scan for each working electrode.

- Mechanically polish the electrode surfaces after every three measurement cycles to ensure reproducibility.

- Convert the obtained CV curve (current vs. potential) to a current-time curve, resulting in 1040 data points per voltammogram.

- Use all 1040 current values as features for machine learning analysis.

- Train machine learning models (e.g., decision trees, random forests) on the dataset to classify the antibiotics.

- Key Data & Outcome: A total of 1377 cyclic voltammograms were used to train a model to discriminate five antibiotics (plus a negative control). The model achieved high classification accuracies, ranging from 0.8 to 1.0. A larger dataset with 2122 voltammograms for 16 classes showed the importance of sufficient data per class, as accuracy dropped to a range of 0.55 to 1.0 [31].

Workflow for Technique Selection and Data Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for selecting an appropriate electroanalytical technique based on research goals and proceeding through data acquisition and interpretation, particularly in the context of redox couple studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting experiments in electroanalytical chemistry, particularly those focused on redox couples.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Research

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Three-Electrode Cell Setup | Fundamental apparatus for controlled-potential experiments. Consists of Working, Reference, and Counter electrodes [30]. |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common inert working electrode for voltammetry of organic molecules and metal ions [32]. |

| Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) | A versatile and easily modifiable working electrode. Used as a base for surfactant or polymer modifications [32]. |

| Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) / Ag/AgCl | Common reference electrodes providing a stable and known reference potential for accurate measurement [32] [30]. |

| Platinum Wire | A common material for the counter electrode, chosen for its inertness [32]. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., Ferrocyanide/Ferricyanide) | Standard redox couples used to validate electrode performance and method functionality [7] [31]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A common supporting electrolyte to maintain constant pH and ionic strength, ensuring current is carried by ionic migration [32]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 80) | Used to modify electrode surfaces to enhance electrocatalytic properties, stability, and prevent fouling [32]. |

Voltammetry, EIS, Amperometry, and Potentiometry each offer unique strengths for the analysis of redox couples in sensing research. The choice of technique is not one-size-fits-all but must be aligned with the specific analytical question, whether it is ultrasensitive detection, mechanistic elucidation, interfacial characterization, or continuous monitoring. The integration of these classical techniques with modern approaches like electrode modification and machine learning is pushing the boundaries of sensitivity and selectivity, enabling the resolution of complex mixtures and the analysis of real-world samples with unprecedented accuracy.

Direct vs. Indirect Detection Strategies for Electroactive and Non-Electroactive Targets

Electrochemical sensing is a powerful analytical technique that merges the specificity of biological recognition with the sensitivity of electrochemical transducers. A fundamental distinction in this field lies in the choice between direct and indirect detection strategies, a choice primarily governed by the inherent electroactivity of the target molecule. Electroactive targets, such as dopamine and serotonin, possess intrinsic chemical properties that allow them to participate in redox reactions at an electrode surface, enabling their direct detection through changes in current or potential [34]. In contrast, non-electroactive targets, including many neurotransmitters like glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), as well as various proteins and environmental contaminants, cannot be directly oxidized or reduced under readily accessible potentials, necessitating the use of sophisticated indirect detection methods [34] [35].

The selection of an appropriate detection strategy is critical for the development of a successful sensor, impacting its sensitivity, selectivity, complexity, and ultimate application potential. This guide provides a comparative analysis of direct and indirect electrochemical detection, framing the discussion within the broader context of evaluating redox couples and sensing mechanisms for research and development. We will explore the fundamental principles, present experimental data and protocols, and provide a practical toolkit for researchers and scientists engaged in drug development and diagnostic sensor design.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison

Core Mechanisms

Direct detection strategies are characterized by the measurement of an electrical signal that arises directly from the interaction between the target analyte and the transducer surface. For electroactive species, this involves the direct oxidation or reduction of the molecule at the electrode, producing a measurable faradaic current. The resulting cyclic voltammogram displays distinct redox peaks whose position and magnitude are characteristic of the analyte [34]. Direct detection can also be employed for non-electroactive targets that modulate electrode properties upon binding; for instance, the specific binding of a protein like HbA1c to an aptamer-modified surface can directly alter the charge transfer resistance, which is measurable via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [36].

Indirect detection strategies, on the other hand, are essential for non-electroactive species. These methods rely on a transduction mechanism that converts the recognition event into a detectable electrochemical signal via a secondary, electroactive reporter. A canonical example is the enzyme-based detection of the neurotransmitter glutamate. The enzyme glutamate oxidase (GluOx) is immobilized on the electrode surface, where it catalyzes the conversion of glutamate into an electroactive byproduct, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). The subsequent oxidation of H₂O₂ at the electrode surface generates a current that is proportional to the original glutamate concentration [34]. Other indirect strategies involve the use of redox probes in solution, whose electrochemical signal is modulated when the target analyte binds to a surface receptor, thereby hindering electron transfer [35].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Disadvantages