pH vs. Redox Potential: A Practical Guide to Measurement Reliability for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the reliability of pH and Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP) measurements, crucial parameters in drug development and clinical research.

pH vs. Redox Potential: A Practical Guide to Measurement Reliability for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the reliability of pH and Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP) measurements, crucial parameters in drug development and clinical research. We explore the fundamental principles governing each measurement, detail methodological best practices and applications, address common troubleshooting and optimization strategies, and present a comparative validation of their respective reliabilities. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current knowledge to empower professionals in making informed decisions for accurate and reproducible data in redox-related and pH-sensitive studies.

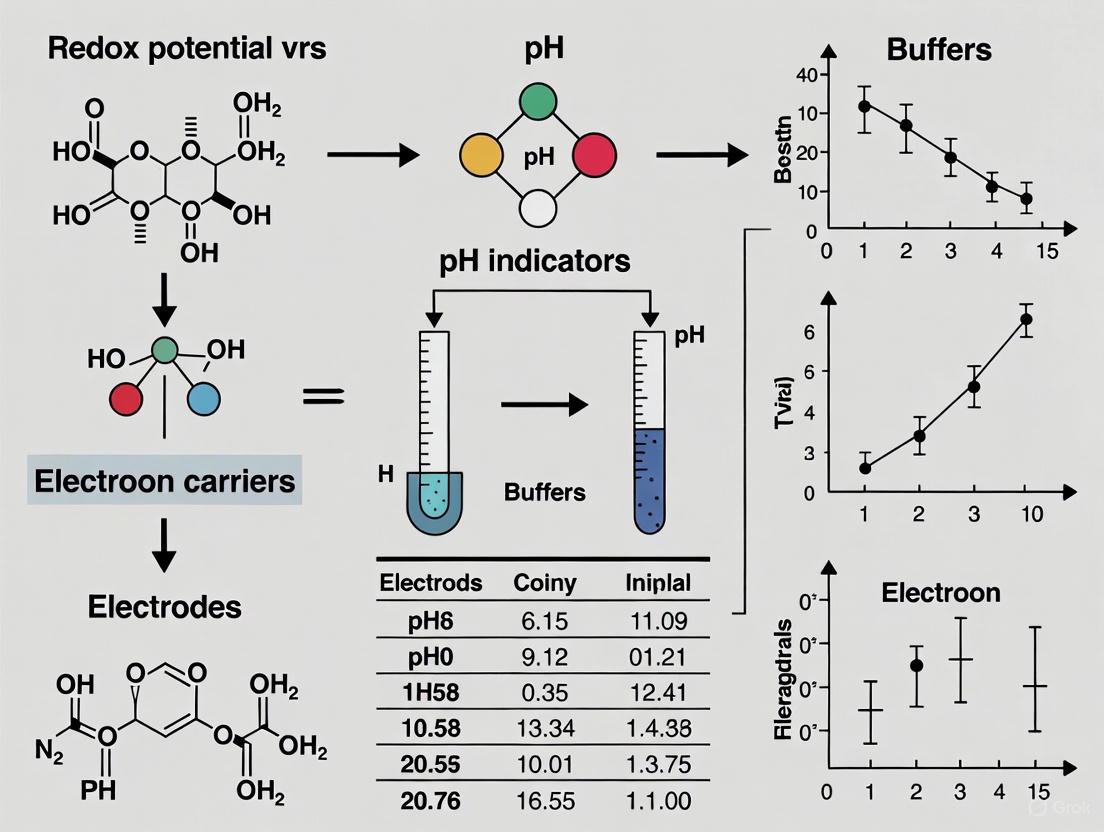

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamental Differences Between pH and ORP

In scientific research and industrial processes, accurately assessing the chemical properties of a solution is paramount. Two fundamental parameters, pH and Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP), serve as critical indicators, yet they measure distinctly different chemical phenomena. Framed within the context of ongoing research into measurement reliability, this guide provides an objective comparison of these parameters, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to aid researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the appropriate measurement technique.

Core Definitions and Scientific Principles

pH: The Measure of Acidity or Alkalinity pH is a concentration measurement that quantifies the activity of hydrogen ions (H⁺) in a water-based solution [1]. It determines whether a substance is acidic, neutral, or alkaline (basic) on a scale typically ranging from 0 to 14 [2]. A pH of 7 is neutral, values below 7 indicate acidity, and values above 7 indicate alkalinity [1]. In practical terms, industries from pharmaceuticals to water treatment rely on pH measurement for quality control, process optimization, and to ensure product stability and efficacy [2].

ORP: The Measure of Oxidizing or Reducing Power Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP), also known as redox potential, measures a solution's ability to either gain or lose electrons in a reduction-oxidation (redox) reaction [3] [2]. It is not a concentration measurement but an electron exchange potential, reported in millivolts (mV) [1]. A positive ORP value indicates an oxidizing environment (electron-accepting), whereas a negative value indicates a reducing environment (electron-donating) [1] [2]. In applications like water disinfection and clinical monitoring, ORP serves as a powerful indicator of sanitation effectiveness and pathological states [3] [1].

The following table summarizes their core characteristics:

| Feature | pH | ORP |

|---|---|---|

| What it Measures | Hydrogen ion (H⁺) activity/concentration [1] | Electron transfer potential (tendency to oxidize or reduce) [1] [2] |

| Measured Quantity | Concentration | Potential (Relative) |

| Scale & Unit | Unitless (0-14 scale) [2] | Millivolts (mV) [1] |

| High Value Meaning | Alkaline/Basic condition [1] | Oxidizing environment (e.g., presence of chlorine, oxygen) [1] |

| Low Value Meaning | Acidic condition [1] | Reducing environment (e.g., presence of antioxidants) [1] |

| Key Application Example | Ensuring drug stability in pharmaceuticals [2] | Monitoring sanitation in water treatment [2] |

Comparison of Measurement Reliability and Challenges

The reliability of pH and ORP measurements is a central point of investigation in redox versus pH research. Both methods are susceptible to distinct sources of error and interference, which can impact the accuracy and interpretation of data, particularly in complex biological or chemical matrices.

pH Measurement Reliability: The accuracy of pH measurement can be influenced by several factors, and inaccuracies can have a cascading effect on other scientific determinations. A key study highlighted that the error in pH measurement directly impacts the accuracy of the acid dissociation constant (pKa) determined by techniques like capillary electrophoresis (CE) and microscale thermophoresis (MST) [4]. This effect is often underestimated, and the resulting uncertainty in pKa can be more significant than commonly assumed [4]. Other critical factors affecting pH electrode accuracy include:

- Temperature: Electrode potential response shifts with temperature changes, making automatic temperature compensation (ATC) essential for high-precision applications [5].

- Electrode Condition: Aging, contamination, or damage to the electrode's sensitive membrane can lead to slowed response speed and zero-point drift [5].

- Calibration: The use of expired or contaminated standard buffer solutions can lead to significant calibration deviations [5].

ORP Measurement Reliability: Traditional ORP measurement methods face challenges related to electrochemical properties and practical usability. A clinical study noted that the traditional method requires a long time to establish potential equilibrium and demands well-maintained, conditioned electrodes to reduce accidental error [3]. This has historically made actual clinical monitoring laborious and difficult [3]. The stability of ORP determinations can be improved by pretreatment of the platinum working electrode and by using methods like the depolarization curve, which helps remove oxide film or other adsorbates from the electrode surface [3].

Experimental Protocol: Clinical Dynamic Monitoring of Redox Status

A 2013 study provides a robust experimental methodology for evaluating a new ORP monitoring technique, offering insights into how measurement reliability can be assessed and improved [3].

1. Objective: To evaluate the reliability of a new depolarization curve method for monitoring plasma redox potential (ORP) in a clinical setting, using the improved traditional relative ORP (ΔORP) method as a reference [3].

2. Materials and Subjects:

- Subjects: The study involved 50 formerly healthy burn patients (30 severe, 20 mild) and one healthy control. Severe burn patients were defined as having >40% total body surface area (TBSA) burns and were assessed using the Abbreviated Burn Severity Index and Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment upon admission [3].

- Sample Handling: Plasma was used for ORP monitoring to avoid influence from blood cells. Determinations were performed under different sample-handling conditions [3].

- Validation Metrics: The erythrocytic methemoglobin (Met-Hb) and uric acid (UA) levels were used as secondary validation, as they reflect the intracellular redox status and antioxidant capacity, respectively [3].

3. Methodology:

- Depolarization Curve Method: This method uses a polarization process to reduce interference by removing any oxide film or adsorbate on the working electrode's surface. This accelerates the redox reaction speed and shortens the measuring time compared to the traditional method [3].

- Redox Titration Experiments: To establish baseline reliability, redox titration experiments were performed using known agents like KMnO₄ (oxidant) and vitamin C (reductant) [3].

- Dynamic Monitoring: Plasma ORP was dynamically monitored in patients from admission to 7 days after injury. Changes prior to death were also observed in non-surviving patients [3].

4. Key Workflow: The experimental workflow for dynamic clinical monitoring of ORP can be summarized as follows:

5. Findings and Data Correlation: The study confirmed that the new depolarization curve method demonstrated better reliability, electrochemical specificity, and practicability. It also showed known group validity, closely associating with redox-related pathological processes in severe burns [3]. Furthermore, the study successfully observed, for the first time, bidirectional changes in the redox status of severe burn patients [3].

The quantitative data from this clinical validation is summarized below:

| Measurement Group | Number of Subjects | Key ORP Findings | Correlation with Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe Burn Survivors | 23 | Dynamic, bidirectional ORP changes observed [3] | Associated with shock, alleviation of symptoms, and recovery [3] |

| Severe Burn Non-Survivors (Sepsis) | 5 | Distinct ORP changes prior to death [3] | Correlated with advanced Pseudomonas aeruginosa sepsis [3] |

| Mild Burn Patients | 20 | Not explicitly detailed | Served as a control group with less severe pathology [3] |

| Healthy Control | 1 | Baseline ORP established [3] | Provided a reference "normal" redox status [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing experiments involving pH and ORP, the following reagents and materials are critical for ensuring data accuracy and reliability.

| Item | Function in pH/ORP Research |

|---|---|

| Standard Buffer Solutions | Essential for regular calibration of pH electrodes. High-quality, precisely prepared solutions prevent calibration deviations [5]. |

| Reference Electrolyte Solution | A replenishable solution for the reference electrode; requires regular replacement to ensure stable potential and smooth ion flow [5]. |

| Chemical Redox Standards (e.g., KMnO₄, Vitamin C) | Used in redox titration experiments to validate ORP method performance and establish baseline measurements [3]. |

| Electrode Cleaning Solutions | Specific solutions for removing contaminants (oils, proteins) from electrode membranes to restore response speed and accuracy [5]. |

| Validation Analytics (e.g., Met-Hb, Uric Acid Kits) | Independent biochemical measures used to cross-validate and confirm findings from ORP measurements in complex biological samples [3]. |

In summary, pH and ORP are distinct yet complementary parameters. pH measures hydrogen ion concentration to define acidity, while ORP measures electron transfer potential to define oxidative or reductive capacity. Research into their measurement reliability reveals that pH accuracy is critically dependent on meticulous electrode maintenance and calibration, as its error can propagate into other derived constants like pKa [4] [5]. ORP reliability, meanwhile, has been enhanced by methodological improvements, such as the depolarization curve, which provides a more stable and practical tool for dynamic monitoring in complex environments like clinical settings [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between monitoring pH, ORP, or both depends entirely on the scientific question. pH is indispensable for controlling reaction conditions and product stability. In contrast, ORP is a powerful tool for investigating oxidative stress, antioxidant efficacy, and sanitization processes. A clear understanding of what each parameter measures, alongside a rigorous application of standardized experimental protocols, is fundamental to generating reliable and meaningful data.

The Nernst equation is a fundamental principle in electrochemistry and thermodynamics that quantitatively describes the relationship between the reduction potential of an electrochemical reaction and the activities (or concentrations) of the chemical species involved. Formulated by Walther Nernst in the late 19th century, this equation serves as a critical tool for predicting the direction and extent of redox reactions under non-standard conditions [6] [7]. Its importance extends across numerous scientific disciplines, from guiding the understanding of subsurface geochemistry and contaminant transport in hydrology to enabling the measurement of redox balance in the human gut for medical diagnostics [8] [9]. The equation's capacity to link thermodynamic driving forces with measurable experimental parameters makes it indispensable for both theoretical analysis and practical application in research and industry.

This article examines the central role of the Nernst equation, focusing specifically on its application in comparing the reliability of two fundamental measurement types: redox potential (Oxidation-Reduction Potential, ORP) and pH. While both parameters are essential for characterizing chemical environments, they present distinct challenges in measurement reliability and interpretation. By exploring the theoretical underpinnings and practical implementations of the Nernst equation across different experimental contexts, this analysis provides researchers with a framework for evaluating the relative strengths and limitations of redox potential versus pH measurements in diverse experimental systems.

Theoretical Framework of the Nernst Equation

Mathematical Formulation and Interpretation

The Nernst equation provides a quantitative relationship between the reduction potential of an electrochemical half-cell reaction and the standard electrode potential, temperature, and activities of the reacting species. For a general reduction reaction of the form: [ \text{Ox} + ze^- \rightarrow \text{Red} ] the Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}} ] where:

- (E_{\text{red}}) is the half-cell reduction potential at the temperature of interest,

- (E_{\text{red}}^{\ominus}) is the standard half-cell reduction potential,

- (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹),

- (T) is the temperature in kelvins,

- (z) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction,

- (F) is Faraday's constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹),

- (a{\text{Red}}) and (a{\text{Ox}}) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [6].

At room temperature (25°C), this equation can be simplified using logarithmic properties and constants to: [ E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{0.059}{z} \log_{10} \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]} ] where the numerical constant 0.059 V (approximately 59 mV) represents ( \frac{2.3026RT}{F} ) at 25°C [7]. This formulation highlights that a half-cell potential changes by 59/z millivolts per tenfold change in the concentration ratio of the reduced to oxidized species for a one-electron transfer process.

The Nernst equation was originally derived for galvanic cell reactions involving the same ion species, but its application has been extended to membrane electrodes including pH glass electrodes and ion-selective electrodes, though not without controversy regarding the mechanistic interpretation of these applications [10]. The equation essentially represents the point of electrochemical equilibrium where the tendency for reduction is balanced by the tendency for oxidation, providing a thermodynamic basis for predicting reaction spontaneity.

The Concept of Formal Potential

In practical laboratory settings where chemical activities are often unknown or difficult to determine, the Nernst equation is frequently applied using concentrations rather than activities. This approach introduces the concept of formal reduction potential ((E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'})), which incorporates the activity coefficients into a modified standard potential: [ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]} ] where (E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'}) is the formal potential defined as: [ E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{\gamma{\text{Red}}}{\gamma{\text{Ox}}} ] with (\gamma) representing the activity coefficients [6].

The formal potential is experimentally measured under conditions where the concentrations of oxidized and reduced species are equal (([\text{Red}]/[\text{Ox}] = 1)), effectively making the logarithmic term zero and yielding (E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'}) [6]. This practical parameter accounts for medium effects and provides a more applicable reference for specific experimental conditions than the theoretical standard potential, making it particularly valuable for biological and environmental systems where ideal conditions rarely exist.

Diagram 1: Relationship between standard and formal potential in the Nernst equation.

Comparative Reliability: Redox Potential vs. pH Measurement

Fundamental Measurement Principles

Both redox potential and pH measurements are electrochemical techniques that rely on the Nernst equation, but they detect different chemical properties. pH measurement quantifies hydrogen ion activity in solution, reflecting acid-base balance, while redox potential (ORP) measures electron transfer capacity, indicating the balance between oxidizing and reducing agents [11].

pH sensors employ a glass membrane that develops a potential proportional to hydrogen ion concentration, with the measured potential following the Nernstian relationship: [ E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{2.303RT}{F} \text{pH} ] In practice, this creates a linear response of approximately 59 mV per pH unit at 25°C [12].

ORP measurements utilize an inert noble metal electrode (typically platinum or gold) that responds to the ratio of oxidizing to reducing agents in solution, generating a potential described by the Nernst equation for the specific redox couples present [11]. The measured ORP represents a mixed potential reflecting all redox-active species in the solution, not just a single redox couple.

Reliability Challenges in Complex Environments

Redox potential measurements face significant reliability challenges in complex biological and environmental matrices. Unlike pH measurements which target a specific ion (H⁺), ORP measurements respond to all redox-active species in solution, making them non-specific and difficult to interpret in systems with multiple redox couples [11]. Recent research highlights several critical limitations:

Instability and Fluctuation: Studies measuring fecal redox status in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) research found ORP measurements to be "highly unstable and rapidly fluctuated throughout time," with values varying from +24 to +303 mV in the same sample [13]. This instability complicates data interpretation and reduces reliability for diagnostic applications.

Lack of Diagnostic Discrimination: Attempts to use ORP measurements to distinguish between healthy controls and IBD patients showed no significant differences (median 46.5 mV vs. 25.0 mV, p = 0.221), suggesting limited utility for clinical discrimination in this context [13].

Electrode Complications: ORP sensors suffer from similar limitations as pH electrodes, including coating of the metal measuring electrode (causing sluggish response) and poisoning of the reference electrode by ions such as sulfide, cyanides, and bromides that react with silver in the reference electrode [11].

Interpretation Challenges: Natural waters commonly contain multiple redox species not in mutual equilibrium, making it difficult to reliably represent redox conditions with a single Eh value [8]. Electrode potentials frequently diverge from reduction potentials calculated via the Nernst equation for individual redox couples [8].

In contrast, pH measurements benefit from greater reliability due to:

Standardized Methodology: Well-established calibration procedures using standard buffer solutions [10].

Predictable Temperature Dependence: Automatic Temperature Compensation (ATC) capabilities in modern sensors effectively correct for physical changes in the sensor response [12].

Specific Response: Targeting of a single, well-defined ionic species (H⁺ or OH⁻) rather than multiple competing redox couples [10].

Diagram 2: Fundamental differences between pH and redox potential measurement principles.

Experimental Applications and Protocols

Advanced Sensing Technologies

Recent technological advances have enabled more sophisticated applications of Nernst-based measurements in challenging environments. The GISMO (GI Smart Module) represents a cutting-edge application of Nernst principles in clinical diagnostics [9]. This miniaturized ingestible sensor (21 mm × 7.5 mm) simultaneously measures ORP, pH, and temperature throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract, providing high-temporal-resolution data every 20 seconds [9].

Experimental Protocol - In Vivo Redox Mapping:

- Sensor Design: Incorporates a platinum ORP working electrode, custom electrochemical reference electrode, and ISFET-based pH sensors hermetically sealed in a biocompatible PEEK housing [9].

- In Vivo Validation: Preclinical validation in GI fluids and animal models followed by human trials in 15 healthy individuals [9].

- Data Collection: Continuous wireless transmission of ORP, pH, and temperature measurements to an external wearable receiver during normal GI transit [9].

- Results: Revealed consistent redox profiles transitioning from an oxidative environment in the stomach to a strongly reducing environment in the large intestine, demonstrating the Nernst equation's applicability even in complex biological systems [9].

Simplified Field-Based Applications

In environmental science, researchers have developed simplified Nernst-based approaches to overcome practical field constraints. A recent innovation involves a data-driven simplified Nernst equation that estimates reduction potentials of individual redox couples using only pH and temperature, excluding difficult-to-measure redox species activities [8].

Experimental Protocol - Groundwater Redox Assessment:

- Dataset Assembly: Compiled 362,424 data points from the USGS National Water Information System and 57,791 points from the Global Freshwater Quality Database [8].

- Data Quality Control: Removed samples with charge balance error >10% and identified outliers using interquartile range method [8].

- Model Development: Integrated geochemical modeling with global groundwater chemistry data to demonstrate pH as the dominant control on redox potential, with temperature and redox species activity playing secondary roles [8].

- Validation: Resulting formulation maintained predictive accuracy while reducing computational demands, enabling rapid estimation of reduction potentials across diverse groundwater environments [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Nernst Equation Applications in Different Experimental Contexts

| Application Domain | Experimental Protocol | Key Parameters Measured | Reliability Assessment | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Gut Monitoring [9] | Ingestible capsule with Pt electrode, reference electrode, and pH sensors; wireless data transmission | ORP, pH, temperature every 20s throughout GI tract | High-resolution mapping possible; technical validation required for each biological context | Miniaturization constraints; complex biofouling management; ethical approvals for human studies |

| Environmental Water Assessment [8] | Field sampling with laboratory analysis; geochemical modeling; big data analytics | pH, temperature, major ions, redox-active species | Predictive accuracy maintained with simplified inputs; enables large-scale application | Requires charge balance validation (<10% error); limited to specific groundwater environments |

| Fecal Redox Status [13] | Fecal water preparation (0.1 g/mL suspension); ORP measurement with Pt/Au electrode and Ag/AgCl reference | ORP values over 3-minute measurement period | Low reliability; high instability (+24 to +303 mV fluctuations); poor diagnostic discrimination | Complex matrix interference; rapid temporal fluctuations; limited clinical utility demonstrated |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nernst-Based Measurements

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum Electrode [11] | ORP measuring electrode; provides inert surface for electron transfer during redox reactions | Nobel metal with excellent chemical resistance; may suffer from chemisorption in strongly oxidizing/reducing solutions | Standard for most ORP measurements; suitable for various environmental and biological matrices |

| Gold Electrode [11] | Alternative ORP electrode for extreme conditions; better performance in strongly oxidizing/reducing solutions | Not recommended with cyanide, chloride, or bromide due to corrosion susceptibility | Specialized applications where platinum performance is compromised |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode [9] [11] | Provides stable reference potential for both ORP and pH measurements; completes electrical circuit | Contains Ag/AgCl wire in KCl gel saturated with AgCl; stable potential relies on constant Cl⁻ concentration | Universal reference system for most electrochemical measurements; requires proper junction maintenance |

| ISFET pH Sensor [9] | Solid-state pH measurement based on ion-sensitive field-effect transistor technology | Chemically inert glass-like oxide surface; withstands acidic environments; compatible with miniaturization | Ingestible sensors and applications requiring small form factors |

| ORP Calibration Standards [9] [11] | Verification of ORP sensor response and accuracy at specific potential points | Commercial standards typically at +220 mV and +600 mV; negative standards prepared in-house | Limited commercial availability, especially for negative ORP values; requires custom preparation |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) Assay [14] | Chemical probe for assessing oxidative potential (OP) of environmental samples | Measures electron transfer from DTT to redox-active species; simulates biological oxidative stress | Air particulate matter toxicity screening; standardized protocols emerging through interlaboratory comparisons |

The Nernst equation remains fundamentally central to interpreting both redox potential and pH measurements across diverse scientific domains. However, significant differences in measurement reliability necessitate careful consideration in experimental design and data interpretation.

For applications requiring high reliability and reproducibility, pH measurements generally provide more robust and interpretable data, benefiting from standardized methodology, predictable temperature dependencies, and specific response to a well-defined chemical species [10] [12]. The theoretical foundation of pH measurement based on the Nernst equation is well-established and consistently applicable across most experimental conditions.

In contrast, redox potential measurements present substantial reliability challenges, particularly in complex biological and environmental matrices [8] [13]. The non-specific nature of ORP measurements, sensitivity to multiple interfering factors, and instability in complex samples limit their utility for quantitative assessment. When ORP measurements are essential, researchers should:

- Implement rigorous calibration and validation protocols, potentially using higher-order derivative spectroelectrochemical methods to improve formal potential determination [15].

- Recognize the inherent limitations of ORP for diagnostic applications, particularly in heterogeneous biological samples like fecal matter [13].

- Consider simplified Nernst-based approaches that leverage dominant controlling factors (like pH) when comprehensive speciation data is unavailable [8].

The choice between prioritizing redox potential versus pH measurements should be guided by the specific research question, matrix complexity, and required reliability threshold. While the Nernst equation provides the theoretical foundation for both parameters, its practical implementation reveals fundamentally different reliability profiles that must inform experimental design in research and drug development.

In scientific research and industrial processes, both pH and Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP) serve as critical parameters for characterizing solution properties. However, their fundamental measurement principles dictate significantly different stability profiles, with pH demonstrating inherent stability advantages over ORP for reliable quantification. pH measures the negative logarithm of hydrogen ion activity in a solution, representing a specific chemical entity concentration [16] [2]. In contrast, ORP measures the collective electron transfer tendency of all redox-active species present in a solution, representing a non-specific, system-level potential [16] [2]. This fundamental distinction establishes pH as a property of the solvent system itself, while ORP constitutes a property of the solute mixture, making the former inherently more stable and predictable than the latter.

The broader thesis of comparing redox potential versus pH measurement reliability reveals that this stability differential has profound implications across research fields, particularly in drug development where measurement consistency directly impacts experimental reproducibility, process validation, and therapeutic efficacy. Understanding the sources and magnitude of ORP variability compared to pH stability enables researchers to design more robust experiments, implement appropriate controls, and accurately interpret analytical data, particularly in pharmaceutical formulations and biological systems where multiple redox couples coexist [17] [18].

Comparative Stability Analysis: Quantitative Evidence

The stability disparity between pH and ORP measurements emerges clearly from experimental data across multiple research domains. The following comparative analysis summarizes key quantitative evidence demonstrating the superior stability and predictability of pH measurements compared to ORP.

Table 1: Comparative Stability Factors for pH and ORP Measurements

| Factor | pH Measurement Impact | ORP Measurement Impact | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer Capacity | High stability in buffered systems; resists change from additive introduction [19] | Minimal buffer-like protection; directly altered by any redox-active species [19] | Hydroponic nutrient solutions showed pH stability with buffering while ORP fluctuated independently [19] |

| Temperature Sensitivity | Predictable, quantifiable effect following established thermodynamic principles [20] | Significant, variable influence depending on specific redox couples present [21] | ORP changes ~30mV per 20°C at pH 7 with saturated H₂; comparable to 10x H₂ concentration change [21] |

| Measurement Accuracy | Typical laboratory accuracy ±0.1 pH units with proper calibration [20] | Instrument error ±10mV causes H₂ concentration errors up to 125% at saturation [21] | ORP meter inaccuracy makes comparative H₂ concentration assessments unreliable [21] |

| Multi-parameter Dependency | Primarily dependent on [H⁺] concentration and temperature [16] [20] | Dependent on all redox couples, pH, temperature, and dissolved gases [22] [21] | ORP influenced by pH changes more than by varying H₂ concentration over relevant ranges [21] |

Table 2: Impact of Environmental Factors on pH and ORP Stability

| Environmental Factor | Effect on pH | Effect on ORP | Clinical/Experimental Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Handling | Minimal change with proper technique; stable in closed systems [23] | Significant degradation with freeze-thaw cycles (6-25mV decrease) [17] | Plasma ORP measurements require immediate analysis without freeze-thaw for accuracy [17] |

| Anticoagulant Selection | Negligible effect with standard anticoagulants [17] | Substantial variation (28mV difference citrate vs. heparin) [17] | Heparin preferred for ORP measurement in clinical samples; citrate increases values [17] |

| Chemical Additives | Predictable changes based on acid-base equilibrium [16] | Variable response depending on redox couples affected [19] | ORP decreased with ascorbic acid but response varied with anticoagulant [17] |

| Time-dependent Changes | Gradual drift primarily from CO₂ absorption/desorption [20] | Continuous fluctuation from oxygen consumption/production [19] | ORP trends downward over time even with high dissolved oxygen [19] |

ORP measurements exhibit inherent instability due to their cumulative nature, where the measured potential represents the net electron flux between all oxidized and reduced species present in a solution [16] [2]. This section examines the primary factors contributing to ORP variability in research environments, particularly those relevant to drug development and biological systems.

pH Interference with ORP Measurements

The inverse logarithmic relationship between pH and ORP creates substantial stability challenges, as minor pH variations create significant ORP fluctuations. Experimental analyses demonstrate that a single unit increase in pH influences ORP as dramatically as increasing hydrogen gas concentration by 100-fold [21]. This profound pH dependency means that ORP measurements cannot be meaningfully interpreted without simultaneous pH monitoring, and apparent ORP changes may primarily reflect pH variation rather than actual redox state alterations.

Figure 1: Differential Factor Influence on pH and ORP. ORP is strongly influenced by multiple competing factors, while pH is primarily determined by hydrogen ion concentration with predictable temperature effects.

Complex Biological and Chemical Interferences

ORP measurements in biological systems exhibit exceptional vulnerability to interference from diverse redox-active compounds. Research demonstrates that blood plasma ORP values vary significantly based on anticoagulant selection, with heparinized plasma measuring approximately 28mV lower than citrated plasma from the same subjects [17]. This variability stems from differential interactions between anticoagulants and redox couples rather than actual redox state differences. Furthermore, biological ORP measurements degrade with standard laboratory handling practices, exhibiting significant decreases after freeze-thaw cycles (6-25mV reduction) [17].

In pharmaceutical applications, ORP instability presents both challenges and opportunities. Drug delivery systems exploit redox gradients between extracellular and intracellular environments for targeted drug release, utilizing the predictable 100-1000-fold higher glutathione concentrations inside cells compared to extracellular spaces [18]. However, this same sensitivity complicates ORP measurement reliability for quality control, as multiple competing redox couples create unpredictable potential fluctuations that don't correlate with specific analyte concentrations.

Measurement Protocols and Methodological Considerations

Standardized measurement protocols highlight the stability differential between pH and ORP, with pH methodologies offering significantly better reproducibility across research environments.

pH Measurement Standardization

Comprehensive Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for pH measurement emphasize calibration integrity, electrode compatibility, and sample handling consistency [23]. Critical protocol elements include:

- Instrument Setup: Verification of electrode and meter compatibility with specific sample matrices [23]

- Calibration Protocol: Bracket samples with at least two standard buffers on both sides of expected values [23]

- Slope Validation: Ensure electrode response falls within acceptable ranges (typically 95-102% of theoretical) [23]

- Sample Measurement: Standardize measurement duration, stirring conditions, and temperature equilibration [20] [23]

These established protocols yield reproducible accuracy of approximately ±0.1 pH units in laboratory settings when properly implemented [20]. The fundamental stability of pH as a parameter enables this level of reproducibility across different instruments, operators, and laboratories.

ORP Measurement Challenges

ORP measurement protocols lack equivalent standardization due to the parameter's inherent variability. Methodological challenges include:

- Reference Electrode Compatibility: Unlike pH measurement with standardized reference systems, ORP reference electrodes introduce additional redox couples that may affect measurements [21]

- Chemical Equilibrium Requirements: ORP readings may drift continuously as redox equilibria establish slowly in complex solutions [19]

- System-specific Interpretation: Calibration standards cannot be universally applied since ORP values are system-specific rather than absolute [21]

Experimental workflows must account for these limitations through careful experimental design that incorporates multiple controls and parallel measurement strategies.

Figure 2: Differential Workflow Complexity for pH versus ORP Measurements. The ORP measurement pathway requires more controls and complex interpretation compared to the standardized pH measurement process.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing reliable pH and ORP measurements requires specific research reagents and materials. The following toolkit details essential solutions for proper measurement protocols in experimental research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for pH and ORP Measurements

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Buffer Solutions | pH meter calibration with known accuracy (±0.03 pH) [20] | Fundamental limit for pH measurement accuracy; use at least two buffers bracketing sample [23] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide Solutions | ORP system oxidant for response validation [17] | Titration (0.03-10%) tests ORP system response to controlled oxidation [17] |

| Ascorbic Acid Solutions | ORP system reductant for response validation [17] | Titration (10-50mM) tests ORP system response to controlled reduction [17] |

| Heparin Anticoagulant Tubes | Blood collection for plasma ORP measurement [17] | Provides lower, more consistent baseline ORP than citrate in biological samples [17] |

| K₂CO₃ or Similar Buffers | pH stabilization in experimental solutions [19] | Maintains pH stability independent of dissolved oxygen fluctuations [19] |

| RedoxSYS Diagnostic System | Standardized ORP measurement in biological samples [17] | Disposable electrode platform for clinical ORP measurement with defined protocols [17] |

Implications for Research and Drug Development

The stability differential between pH and ORP measurements carries significant implications for research design and interpretation, particularly in pharmaceutical development and biological studies.

Drug Delivery System Design

Smart drug delivery systems exploit the comparative stability of pH versus the variability of ORP for controlled therapeutic release. Polymeric micelles and prodrug constructs incorporate acid-labile linkages (hydrazone, acetal, orthoester) that remain stable at physiological pH (7.4) but hydrolyze in acidic tumor microenvironments (pH 6.5-6.7) or endosomal compartments (pH 5.5-6.0) [18]. This approach leverages the predictable pH gradient between normal and pathological tissues, whereas ORP-responsive systems must accommodate substantial variability in redox potential across similar biological environments.

Core cross-linked prodrug micelles with dual pH/redox sensitivity demonstrate sophisticated engineering that acknowledges this stability differential, using pH responsiveness for primary targeting and redox sensitivity for intracellular activation [18]. The diselenide bonds in these systems respond to the dramatic (100-1000x) glutathione concentration differential between intracellular and extracellular compartments, while pH-sensitive components trigger initial endosomal escape [18].

Quality Control and Analytical Methodology

Pharmaceutical quality control protocols prioritize pH monitoring for product consistency while approaching ORP measurements with caution. Studies indicate that ORP should not be used to estimate or compare aqueous hydrogen concentrations due to excessive measurement error and multifactorial interference [21]. ORP meter inaccuracies of ±10mV translate to hydrogen concentration errors up to 125% at saturation levels, while pH changes influence ORP more significantly than actual hydrogen concentration variations [21].

This fundamental limitation necessitates alternative analytical approaches for redox-active species quantification, including direct measurement techniques like gas chromatography for dissolved hydrogen or specific analytical methods for individual redox couples rather than reliance on collective ORP measurements [21].

The inherent stability disparity between pH and ORP measurements stems from fundamental differences in what these parameters represent: pH quantifies the specific activity of hydrogen ions, while ORP reflects the nonspecific net potential of all redox-active species in a system. Experimental evidence consistently demonstrates that pH measurements offer superior reproducibility, predictable temperature dependence, and reliable quantification across diverse research environments. ORP measurements remain valuable for assessing general redox trends but suffer from multifactorial interference, system-specific interpretation requirements, and limited comparative utility between different experimental systems. Research professionals should prioritize pH monitoring for stability-critical applications while implementing ORP measurements with appropriate controls and recognition of their inherent limitations, particularly in pharmaceutical development and biological research where multiple redox couples compete to establish the measured potential.

Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP) and pH are fundamental water quality parameters, yet they represent fundamentally different types of measurements. While pH measures the simple concentration of hydrogen ions, ORP provides a composite, system-level reading of the net balance between oxidizing and reducing agents in a solution. This article explores the multivariate nature of ORP measurement, its inherent complexities compared to pH, and the implications for research and drug development. Through experimental data and computational analysis, we demonstrate why ORP represents a challenging, yet invaluable, system-level metric for assessing redox status in biological and chemical systems.

Fundamental Principles: ORP vs. pH

Table 1: Core Differences Between pH and ORP Measurements

| Parameter | pH | ORP |

|---|---|---|

| Measures | Hydrogen ion concentration | Electron transfer potential |

| Scale | 0-14 (unitless) | Millivolts (mV) |

| Output | Acidic/alkaline state | Oxidizing (positive mV) or reducing (negative mV) state |

| Primary Relationship | Concentration measurement | System-level net potential |

| Measurement Basis | Voltage converted to concentration value | Direct millivolt reading |

At the molecular level, pH is a concentration measurement that quantifies the activity of hydrogen ions in a solution, determining its acidic or alkaline nature [24]. In contrast, ORP is an activity measurement that quantifies the tendency of a solution to either gain or lose electrons when an electrode is introduced [24] [2]. It represents the net balance of all oxidizing and reducing agents present, making it a composite, system-level reading rather than a measure of a specific analyte.

The Multivariate Nature of ORP: Experimental Evidence

Instability and Measurement Challenges in Biological Systems

ORP measurement proves particularly challenging in complex biological environments. A 2023 proof-of-concept study investigating fecal redox status in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) patients highlighted significant measurement instability. Researchers found ORP measurements were "highly unstable and rapidly fluctuated throughout time, with ORP values varying from +24 to +303 mV" [25]. This variability, attributed to potential biological processes and equipment limitations, led the authors to conclude that ORP quantification may not be a suitable method for assessing fecal redox status, underscoring the measurement's sensitivity to complex matrix effects.

The Critical Influence of pH on ORP

The relationship between ORP and pH is not merely comparative but often inversely related. The effectiveness of common oxidizing agents is highly dependent on pH. For instance, chlorine's efficacy as a disinfectant is maximized at lower pH levels, where it contributes more strongly to higher ORP readings [24]. This demonstrates that ORP is not an independent variable but is modulated by the pH environment, adding a layer of complexity to its interpretation.

Computational and Modeling Challenges

Advanced Modeling Requirements for Redox Prediction

The accurate computational prediction of redox potentials requires sophisticated models that far exceed the simplicity of pH estimation. A 2025 study on iron complexes demonstrated that a three-layer micro-solvation model was necessary to achieve accurate predictions [26]. This model combines:

- DFT-based geometry optimizations of the metal complex

- Two layers of explicit water molecules to capture solute-solvent interactions

- An implicit solvation model to account for bulk solvent effects

This hybrid approach yielded highly accurate predictions for Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ redox potentials in water, with errors as low as 0.01-0.04 V across different functionals [26].

Benchmarking Computational Methods

Table 2: Performance of Computational Methods for Reduction Potential Prediction (Mean Absolute Error in Volts)

| Method | Main-Group Species (OROP) | Organometallic Species (OMROP) |

|---|---|---|

| B97-3c (DFT) | 0.260 | 0.414 |

| GFN2-xTB (SQM) | 0.303 | 0.733 |

| UMA-S (Neural Network) | 0.261 | 0.262 |

Recent benchmarking of neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on large computational datasets reveals the challenging landscape of redox potential prediction. While these models show promise, their performance varies significantly between chemical classes. For instance, the UMA-S model achieved comparable accuracy to DFT methods for main-group species (MAE: 0.261 V) but significantly outperformed semiempirical quantum mechanical methods for organometallic species (MAE: 0.262 V) [27]. This specialized performance highlights how redox behavior is sensitive to molecular architecture in ways that pH is not.

Case Study: Machine Learning Approaches for Complex System Prediction

Successful pH Prediction in Biomaterials

The relative simplicity of pH as a measurement is demonstrated by recent success in machine learning prediction models. Researchers developed a hybrid stacked ensemble model to predict long-term pH profiles (up to 672 hours) of calcium silicate-based cements using only early-stage pH measurements (3 and 24 hours) and specimen surface area [28] [29]. The model achieved high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.91, 0.89, and 0.85 for 72, 168, and 672 h) with consistent performance across validation folds [28]. This level of predictability from minimal inputs underscores how pH, while dynamic, follows more deterministic patterns compared to ORP.

Biological System Complexity: Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

In mitochondrial bioenergetics, the relationship between redox potential and membrane potential illustrates sophisticated system-level interdependence. The redox potentials of the hemes in the mitochondrial bc₁ complex are directly dependent on the proton-motive force, allowing membrane potential (ΔΨ) and pH gradient components to be calculated from the oxidation state of the hemes [30].

Diagram Title: Mitochondrial Redox & Energy Relationship

This technique enables "absolute quantification of the membrane potential, pH gradient, and proton-motive force without the need for genetic manipulation or exogenous compounds" [30], but requires complex modeling of the entire system rather than simple direct measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Redox Potential Research

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ORP Electrode | Measures oxidation-reduction potential in mV | Uses platinum/gold sensing electrode with Ag/AgCl reference junction [25] |

| pH Electrode | Measures hydrogen ion concentration | Requires different buffer solutions for calibration |

| Three-Layer Micro-Solvation Model | Computational prediction of metal ion redox potentials | Combines explicit water molecules with implicit solvation [26] |

| Multi-Wavelength Cell Spectrometer | Measures oxidation states of hemes in living cells | Enables quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential [30] |

| Stacking Ensemble Machine Learning Model | Predicts long-term pH profiles from early measurements | Uses GBR base models with neural network meta-model [28] |

| Polarizable Continuum Models (PCM, CPCM, COSMO) | Implicit solvation for computational chemistry | Treats solvent as continuous polarizable medium [26] |

ORP measurement represents a fundamentally different challenge compared to pH analysis. Where pH measures a specific concentration of hydrogen ions, ORP provides a system-level integration of all redox-active couples in a solution, making it inherently multivariate and context-dependent. The experimental evidence demonstrates that ORP values are highly sensitive to multiple factors including pH, specific chemical environment, and biological matrix effects. This complexity necessitates advanced computational models, sophisticated measurement protocols, and system-level thinking for accurate interpretation. For researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing ORP as a composite, system-level metric rather than a straightforward analyte measurement is crucial for appropriate experimental design and data interpretation in redox-related studies.

From Theory to Bench: Standardized Methods for pH and ORP in the Lab

In scientific research and drug development, the reliability of analytical measurements forms the foundation upon which valid conclusions are built. Measurements of oxidation-reduction potential (ORP) and pH are critical process variables across biological, pharmaceutical, and environmental applications. However, these two measurements differ significantly in their inherent reliability and dependence on standardized procedures. While pH measurement has matured into a highly reproducible technique thanks to well-established protocols, ORP measurement remains fraught with challenges, including electrode instability, susceptibility to interference, and complex interpretation. This comparison guide examines the distinct reliability profiles of ORP versus pH measurement, underscoring how Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) are not merely beneficial but essential—particularly for ORP—to generate trustworthy, reproducible data. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this distinction is crucial for designing robust experiments and ensuring data integrity in redox-related studies.

Fundamental Principles: pH and ORP Measurement

pH Measurement

pH, standing for 'potential of hydrogen,' measures the acidity or alkalinity of a solution on a scale from 0 to 14 [2]. It determines the concentration of hydrogen ions in a solution, with each unit representing a tenfold difference in ion concentration [31]. The measurement is based on the voltage generated by a glass electrode sensitive to hydrogen ions when immersed in a solution [31]. pH is a fundamental parameter in pharmaceutical manufacturing, influencing drug efficacy, stability, and enzymatic activity [2].

ORP (Oxidation-Reduction Potential) Measurement

ORP, in contrast, quantifies a solution's ability to either donate or accept electrons during chemical reactions, expressed in millivolts (mV) [32]. Positive ORP values indicate an oxidizing environment, while negative values suggest a reducing environment [32]. ORP reflects the comprehensive effect of all redox buffer systems in a sample, providing insight into the overall redox status rather than the activity of a specific molecule [3]. In biological systems, the extracellular redox environment dynamically influences cell-cell communication and function, making ORP monitoring valuable for understanding redox-related pathological processes [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of pH and ORP Measurements

| Characteristic | pH Measurement | ORP Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| What it measures | Hydrogen ion activity | Electron transfer potential |

| Measurement scale | 0-14 (logarithmic) | Millivolts (mV) |

| Key significance | Acidity/alkalinity | Oxidizing/reducing capacity |

| Primary applications | Buffer preparation, cell culture, enzyme kinetics, quality control | Water disinfection, redox status monitoring, wastewater treatment |

| Theoretical basis | Nernst equation for H⁺ ions | Nernst equation for multiple redox couples |

Comparative Reliability: Key Challenges and Standardization Needs

pH Measurement Reliability

pH measurement benefits from well-understood chemistry and established standardization protocols. Modern pH meters are designed for simplicity and ease-of-use, incorporating features like automatic temperature compensation (ATC) to minimize variability [31]. The creation of a thorough pH measurement SOP ensures that all laboratory personnel use identical techniques for calibration and measurement, leading to consistent, accurate, and precise results across the organization [23]. Regular calibration using standard buffer solutions, proper electrode handling and storage, and temperature control are established best practices that make pH measurements highly reproducible [31].

ORP Measurement Reliability Challenges

ORP measurement faces significant reliability challenges that heighten its dependence on rigorous SOPs:

Electrode Instability and Drift: Reference electrodes tend to drift over time, intensifying with use and eventually requiring replacement [33]. In pure water, the redox potential drifts in response to dissolved oxygen concentration, trace impurities, or the presence of other solutions [33].

Susceptibility to Interference and Poisoning: ORP electrodes are easily poisoned or fouled by various substances. In wastewater applications, sensors can be fouled by organic molecules within days, requiring frequent cleaning [34]. The presence of cyanuric acid in swimming pools (over 40 ppm) can rapidly poison ORP electrodes [34]. Synthetic perspiration in testing caused ORP sensors to register negative values for over 29 hours due to electrode poisoning [34].

Mixed Potential Limitations: ORP represents a mixed potential in complex solutions like biological samples, where multiple redox couples contribute to the final measurement [35]. Proper interpretation requires kinetic information on electron exchange rates for each couple, which is rarely available [35].

Variable Baseline and Calibration Issues: Different water samples exhibit different ORP baselines, resulting in variations of almost 200 mV for the same chlorine level [34]. ORP sensors from different manufacturers, and even different probes from the same manufacturer, often show significant variations (20-50 mV) in the same water sample [34].

Table 2: Reliability Challenges in ORP versus pH Measurement

| Challenge Factor | pH Measurement | ORP Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode stability | Stable with proper maintenance | Prone to drift; requires frequent reconditioning |

| Susceptibility to fouling | Moderate | High; easily poisoned by organics, sulfides, cyanides |

| Standardization | Well-established with certified buffers | Limited standardization; varies between samples |

| Signal-concentration relationship | Linear response to H⁺ activity | Logarithmic relationship to redox couples |

| Baseline variability | Consistent zero point (pH 7) | Variable baseline between different media |

Experimental Data and Methodologies

Clinical ORP Monitoring in Burn Patients

A 2013 study demonstrated a methodological approach to improve ORP reliability in clinical monitoring of burn patients [3]. The research utilized a depolarization curve method to address traditional ORP measurement limitations, including long equilibrium times and electrode instability [3].

Experimental Protocol:

- Subjects: 50 burn patients (30 severe burns, 20 mild burns) and one healthy control [3]

- Sample Handling: Plasma samples were used to avoid interference from blood cells [3]

- Methodology: Traditional relative ORP (ΔORP) method versus new depolarization curve method [3]

- Validation Parameters: Erythrocytic methemoglobin (Met-Hb) and uric acid (UA) levels were used to validate the new method [3]

- Electrode Treatment: Polarization process to remove oxide film or adsorbates on working electrode surface [3]

Results: The new method demonstrated better reliability, electrochemical specificity, practicability, and known group validity closely associated with redox-related pathological processes in severe burns [3]. The study successfully observed bidirectional changes in redox status in severe burn patients for the first time [3].

In Silico Analysis of ORP Limitations for Hydrogen Water

A 2022 in silico analysis examined the relationship between ORP and dissolved hydrogen concentration, revealing significant limitations in using ORP for quantitative assessment [21].

Methodology:

- Computational Approach: Nernst equation calculations for ORP as a function of pH, temperature, and H₂ concentration [21]

- Parameters Analyzed: Individual contributions of pH, temperature, and intrinsic ORP errors compared to H₂ contribution [21]

Key Findings:

- A one-unit increase in pH (e.g., 7→8) influences ORP as much as increasing H₂ concentration by 100 times (e.g., 1→100 mg/L) [21]

- At saturated H₂ concentration (1.57 mg/L) and pH 7, every ΔT of 20°C changes ORP by ≈30 mV, comparable to changing H₂ concentration by a factor of 10 [21]

- ORP meters have an error range of at least ±10 mV, corresponding to a potential error in measured H₂ concentration of nearly 2 mg/L (≈125% error) [21]

Conclusion: pH, temperature, and intrinsic ORP errors can individually influence ORP more than the entire contribution of dissolved H₂ within normal ranges, making consistent H₂ concentration determination impossible using ORP alone [21].

Essential SOPs for Reliable Measurements

Critical Components of pH Measurement SOPs

A comprehensive pH measurement SOP should include [23]:

- Instrument Setup: Detailed instructions for electrode and pH meter setup, including confirmation and error messages [23]

- Calibration Procedures: Steps for preparation and detailed calibration using standard buffers that bracket the expected sample pH range [31]

- Sample Measurement: Standardized sample preparation and measurement procedures [23]

- Troubleshooting Protocols: Defined responses to common errors and resolution methods [23]

Enhanced SOP Requirements for ORP Measurement

ORP measurements demand additional SOP stringency due to their inherent reliability challenges:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Specific protocols for electrode conditioning, especially when transitioning between oxidizing and reducing environments [33]

- Cleaning Frequency: Defined schedules and methods for electrode cleaning using appropriate solutions (distilled water, fine polishing powder) [33]

- Calibration Validation: Regular single-point calibration to redetermine electrode zero point using buffer solutions [33]

- Interference Management: Procedures to identify and address common poisoning agents (sulfides, cyanides, heavy metals, organic compounds) [33] [34]

- Stability Criteria: Minimum settling times after electrode transition between different media types [33]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Reliable ORP and pH Measurements

| Item | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Combined Glass Electrode | pH measurement; sensitive to hydrogen ions | Choose specialized electrodes for specific samples/environments [31] |

| ORP Electrode (Pt or Au) | Redox potential measurement; inert metal surface for electron exchange | Platinum standard; gold for specific applications; surface roughness affects performance [32] [35] |

| Standard Buffer Solutions | pH meter calibration (typically pH 4.0, 7.0, 9.0) | Use fresh, certified buffers; bracket expected sample range [31] |

| ORP Calibration Solution | ORP system verification (e.g., Zobell's solution) | Contains known redox couples; confirms electrode functionality [34] |

| Electrode Storage Solution | Prevents dehydration of sensing bulb | Typically 4M KCl; never use water for long-term storage [36] |

| Electrode Cleaning Solutions | Removes contaminants fouling electrode surfaces | Specific to contaminant type (protein, lipid, inorganic precipitates) [33] |

Measurement Workflows and Reliability Factors

The following diagrams illustrate the standardized workflows for pH and ORP measurements, highlighting critical control points for ensuring reliability.

Diagram 1: pH Measurement Reliability Workflow

Diagram 2: ORP Measurement Reliability Workflow

For researchers and drug development professionals, the distinction between pH and ORP measurement reliability has significant practical implications. While pH measurement benefits from mature, standardized protocols that yield highly reproducible results, ORP measurement demands greater rigor, understanding of limitations, and meticulous adherence to SOPs. The development and implementation of detailed SOPs for ORP measurement is not optional but essential for generating reliable, reproducible data. These SOPs must address electrode pre-treatment, regular calibration, contamination control, and interpretation within the context of a mixed potential. As research continues to illuminate the importance of redox biology in drug mechanisms and disease pathways, improving the reliability of ORP measurements through rigorous standardization represents a critical frontier in measurement science. The evidence clearly indicates that without such standardized approaches, ORP data remain qualitative at best and misleading at worst, potentially compromising research validity and drug development outcomes.

In laboratory research and drug development, accurately measuring the chemical properties of solutions is fundamental. Two key electrochemical parameters are pH, which measures hydrogen ion activity and expresses the acidity or alkalinity of a solution, and oxidation-reduction potential (ORP or redox potential), which quantifies a solution's overall oxidizing or reducing capacity [32]. While ORP is emerging as a valuable metric in fields like environmental health and toxicology for assessing oxidative stress potential of pollutants [37] [14], pH measurement remains the more established, reliable, and widely standardized technique for most laboratory and industrial applications, including pharmaceutical development [38].

The reliability of pH measurement is heavily dependent on a rigorously followed calibration protocol, proper buffer selection, and consistent best practices. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these critical components to ensure measurement accuracy and consistency across scientific disciplines.

Fundamental Principles of pH Measurement

The pH value of a substance represents the negative logarithm of hydrogen ion activity, providing a scale from 0 to 14 that indicates whether a solution is acidic (pH < 7), neutral (pH = 7), or alkaline/basic (pH > 7) [38]. pH is measured potentiometrically using a pH meter, a reference electrode, and a pH probe. The combination electrode measures changes in H+ ion concentrations, generating a millivolt (mV) potential that the meter converts into a pH value [39] [38]. The relationship between mV and pH is described by the Nernst equation, which is temperature-dependent, making temperature control an important factor for high-accuracy measurements [38].

dot-1 pH Measurement Principle

pH Versus Redox Potential: A Reliability Comparison

While both pH and ORP are electrochemical measurements, they serve different purposes and exhibit varying levels of measurement reliability and standardization, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of pH and ORP Measurement Reliability

| Feature | pH Measurement | Redox Potential (ORP) Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Measures hydrogen ion activity [38] | Measures overall electron-transfer capability [32] |

| Standardization | Highly standardized protocols and buffers [40] [38] | Limited standardization; method-dependent variability [37] [14] |

| Primary Applications | Process control, R&D, quality assurance [39] [40] | Disinfection monitoring, oxidative stress assessment [37] [32] |

| Calibration | Uses certified NIST-traceable buffers (e.g., pH 4, 7, 10) [39] [38] | Limited commercial standards; often verified with single-point checks [25] [41] |

| Signal Stability | Generally stable and reproducible with proper technique [42] [40] | Often unstable; fluctuates over time in complex media [25] |

| Sensor Fouling | Managed with established cleaning procedures [42] [39] | Highly susceptible to poisoning by organics and sulfides [25] [41] |

| Quantitative Value | Direct, absolute reading on a universal scale | Relative value; dependent on specific probe and reference system |

A key challenge in ORP measurement is its inherent instability and lack of standardized calculation methods. For instance, a 2023 study found ORP measurements in fecal water to be "highly unstable and rapidly fluctuated throughout time," making it an unreliable diagnostic tool for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease [25]. Similarly, a 2025 comparative study on the oxidative potential (OP) of particulate matter highlighted that different calculation methods for the same assay could yield variations of 12-18%, underscoring the critical impact of protocol choice on results [37]. Recent advances, such as a 2025 report on a miniaturized ingestible sensor, show promise for more stable in vivo ORP measurements, but the technology is not yet widely established [9]. In contrast, pH measurement benefits from well-established protocols, widely available traceable standards, and generally stable readings, making it the more reliable and comparable metric for most laboratory applications.

Detailed pH Calibration Protocol and Buffer Selection

Accurate pH measurement is impossible without proper calibration. The process aligns the meter's readings with known reference points provided by buffer solutions.

Buffer Solutions: Types and Selection

Buffer solutions resist changes in pH when small amounts of acid or base are added [38]. They are characterized by their pH value, buffer capacity (ability to resist pH change), and range (the pH interval over which they are effective).

Table 2: Types of pH Buffer Solutions and Their Applications

| Buffer Type | pH Range | Composition Example | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acidic Buffers | < 7 (e.g., pH 4.0) | Potassium hydrogen phthalate [38] | Fermentation products, electroplating baths (Ni, Cu) [38] |

| Neutral Buffers | ≅ 7.0 | Potassium dihydrogen phosphate & NaOH [38] | Cosmetic/personal hygiene products, microbial cultures [38] |

| Basic/Buffers | > 7 (e.g., pH 10.0) | Sodium carbonate & sodium bicarbonate [38] | Fabric dyeing, electroplating baths (Au, Zn) [38] |

Best Practice for Buffer Selection:

- Always use fresh, high-quality, NIST-traceable buffer solutions to ensure accuracy [42] [38]. Check expiration dates, as buffers—particularly basic ones like pH 10—have a limited shelf life because they can adsorb CO₂ from the air, which lowers their pH [40].

- Select buffers that bracket your expected sample pH. For a two-point calibration, use one buffer below and one above the sample pH. For the highest accuracy over a wider range, a three-point calibration using pH 4, 7, and 10 buffers is recommended [39] [38].

- Ensure the buffers and samples are at the same, stable temperature, as pH is temperature-dependent [42] [38].

Step-by-Step Calibration Procedure

A three-point calibration is the gold standard for high-accuracy measurements [39]. The following workflow outlines the complete calibration and verification process.

dot-2 pH Calibration Workflow

Detailed Calibration Steps:

Pre-Calibration Preparation:

- Inspect the Electrode: Check for cracks in the glass membrane or damage to the reference junction. Replace damaged electrodes [42].

- Clean the Electrode: Rinse the pH probe thoroughly with deionized or distilled water to remove any contaminants. If necessary, clean with a solution appropriate for the contamination (e.g., dilute HCl for inorganic deposits) [42] [39].

- Hydrate the Electrode: If the electrode has dried out, hydrate it by soaking it in a storage solution or pH 4 buffer for the manufacturer-recommended time (e.g., 4 hours) [42] [39].

Perform the Three-Point Calibration:

- Step 1: Mid-Point (pH 7.0). Rinse the probe with clean water and immerse it in the pH 7.0 buffer. Wait for the reading to stabilize (1-2 minutes), then calibrate to the pH 7.0 point. This step sets the zero point [39] [38].

- Step 2: Low-Point (pH 4.0). Rinse the probe, immerse it in the pH 4.0 buffer, wait for stabilization, and calibrate. This sets the slope for the acidic region [39].

- Step 3: High-Point (pH 10.0). Rinse the probe, immerse it in the pH 10.0 buffer, wait for stabilization, and calibrate. This sets the slope for the alkaline region [39].

Post-Calibration Verification:

- Check the Calibration Slope: After calibration, review the slope value calculated by the meter. An optimal slope is between 95% and 105% (or -59.2 mV/pH unit ±5%) [42] [40]. A slope outside this range indicates an aging, dirty, or damaged electrode that requires cleaning or replacement.

- Verify with a Buffer: Periodically verify calibration accuracy by measuring a different buffer solution (e.g., pH 10 if you calibrated with pH 4 and 7) and ensuring the reading is within tolerance [40].

Best Practices for Reliable pH Measurements

- Proper Electrode Storage: Never allow the pH electrode to dry out. For short-term storage, soak the tip in a storage solution or pH 4 buffer. For long-term storage, follow the manufacturer's instructions, which may involve using a cap filled with a solution of 4M KCl [42] [39].

- Consistent Sample Measurement: When measuring samples, gently stir them consistently, preferably using a stir plate without creating a vortex that can draw in air [40]. Always rinse the electrode with deionized water between samples and gently blot it dry with a lint-free wipe to prevent cross-contamination [40].

- Regular Maintenance and Cleaning: Regularly clean the electrode to remove coatings or fouling. Use specific cleaning solutions based on the contaminant (e.g., detergent for oils, pepsin solution for proteins, dilute HCl for scale) [42] [39] [40].

- Understand Sensor Lifespan: pH electrodes have a finite lifespan. Be prepared to replace them when response times become consistently slow, calibrations fail frequently, or the slope cannot be adjusted to within an acceptable range [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for pH Measurement and Calibration

| Item | Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NIST-Traceable Buffer Solutions (pH 4, 7, 10) | Calibration standards for the pH meter [38] | Must be fresh and unexpired; basic pH 10 buffers have a short shelf life [39] [40]. |

| Combination pH Electrode | Sensing element that measures H+ ion activity [38] | Requires proper hydration and cleaning; finite lifespan of 1-2 years with typical use. |

| Laboratory pH Meter | Instrument that displays the pH reading from the electrode. | Should be capable of multi-point calibration and display slope/offset values. |

| Deionized/Distilled Water | For rinsing the electrode between measurements and solutions [39] [40] | Prevents contamination and carryover. |

| Electrode Cleaning Solutions | Removes fouling or coatings from the electrode membrane [42] [39] | Type depends on contaminant (e.g., 0.1M HCl, mild detergent, enzyme solutions). |

| Electrode Storage Solution | Prevents the electrode from drying out and maintains the gel layer [42] [39] | Typically a pH 4 buffer or a KCl-based solution. |

pH measurement, when supported by a rigorous calibration protocol, proper buffer selection, and consistent best practices, provides a highly reliable and reproducible metric for researchers and drug development professionals. While redox potential offers valuable insights in specific applications, its current limitations in standardization and signal stability make it less universally dependable than pH. By adhering to the detailed methodologies and guidelines presented in this comparison, scientists can ensure the accuracy and integrity of their pH-sensitive processes and research outcomes.

In the comparative analysis of redox potential versus pH measurement reliability, Oxidation-Reduction Potential (ORP) measurement stands as a critical technique for assessing the electron-transfer activity in various solutions. While pH measures hydrogen ion activity to determine acidity or alkalinity, ORP quantifies a solution's tendency to either gain or lose electrons, providing vital insights into oxidative stress in biological systems or disinfectant efficacy in water treatment [16]. Traditional ORP measurement methods, however, face significant challenges including electrode fouling, slow stabilization times, and poor reproducibility in complex biological matrices [3]. These limitations have driven the development of advanced techniques, particularly electrode pretreatment protocols and the depolarization curve method, which offer enhanced reliability for critical applications in pharmaceutical research and clinical diagnostics.

Fundamental Principles of ORP Measurement

Theoretical Foundation

ORP measurement operates on electrochemical principles, specifically employing the Nernst equation to relate potential measurements to redox activity. Unlike pH, which measures proton concentration on a logarithmic scale from 0-14, ORP is measured in millivolts (mV) with positive values indicating oxidizing conditions and negative values indicating reducing conditions [16]. The theoretical relationship for a solution containing both oxidized (Ox) and reduced (Red) species can be expressed as:

E = E° - (RT/nF) × ln([Red]/[Ox])

Where E is the measured potential, E° is the standard potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant, and [Red]/[Ox] is the ratio of reduced to oxidized species [21]. This fundamental relationship forms the basis for all ORP measurements, though its practical application faces challenges in complex biological systems where multiple redox couples coexist.

Comparison of ORP and pH Measurement Characteristics

The table below summarizes key differences between ORP and pH measurement techniques:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between ORP and pH Measurement

| Characteristic | ORP Measurement | pH Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Parameter | Electron transfer activity | Hydrogen ion concentration |

| Measurement Units | Millivolts (mV) | pH units (0-14 scale) |

| Electrode Type | Inert metal (Pt, Au) | Glass membrane |

| Typical Applications | Disinfection monitoring, oxidative stress assessment | Process control, corrosion prevention |

| Temperature Dependence | Approximately 0.2-0.3 mV/°C per pH unit shift [21] | Approximately 0.03 pH/°C |

| Standardization | Qualified with Zobell's solution | Buffered standards |

Challenges in Conventional ORP Measurement

Traditional ORP measurement methods face several significant limitations that affect their reliability in research and clinical settings. A primary issue is the lengthy time required to establish equilibrium potential due to limitations in the electrochemical properties of electrodes and complex redox reaction systems in biological samples [3]. This slow stabilization impedes real-time monitoring applications essential for dynamic biological processes.

Electrode fouling presents another critical challenge, particularly in complex matrices like wastewater or biological fluids. ORP electrodes are easily poisoned by organic compounds, proteins, and other contaminants that adsorb to the electrode surface, creating insulating layers that impair electron transfer and produce inaccurate readings [34]. Studies have demonstrated that ORP sensors can register negative values for extended periods (up to 29 hours in one documented case) when exposed to compounds like synthetic perspiration, indicating severe electrode poisoning [34].

Furthermore, conventional ORP measurements exhibit poor reproducibility between different instruments. Different probes from the same manufacturer often show variations of 20-50 mV when measuring the same sample due to differences in electrode surface characteristics and reference electrode potentials [34]. This variability poses significant challenges for standardizing measurements across laboratories and establishing reliable comparative data in multi-center research studies.

Electrode Pretreatment Methods

Platinum Electrode Pretreatment Protocols

Effective electrode pretreatment is essential for reliable ORP measurements, particularly in biological applications. The depolarization curve method incorporates specific polarization processes that help remove oxide films and other adsorbates from the working electrode surface [3]. This pretreatment accelerates redox reaction kinetics and significantly shortens measurement time compared to traditional methods.