Overcoming Kinetic Hurdles: Advanced Strategies for Accurate Redox Signaling Measurement in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing kinetic limitations in redox signaling measurements.

Overcoming Kinetic Hurdles: Advanced Strategies for Accurate Redox Signaling Measurement in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing kinetic limitations in redox signaling measurements. We explore the fundamental principles of redox kinetics, from defining rate constants to understanding short-lived reactive species. The article details current methodological approaches, including real-time fluorescent probes and genetically encoded sensors, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common experimental pitfalls. Finally, we present a comparative analysis of validation techniques to ensure data reliability, equipping scientists with the knowledge to generate more physiologically relevant and reproducible data in redox biology and therapeutic development.

Redox Signaling Kinetics: Decoding the Speed and Limits of Cellular Communication

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Why does my probe signal (e.g., roGFP, H2DCFDA) plateau before my expected stimulus endpoint, suggesting a false equilibrium?

A: This is a classic sign of kinetic limitation, where the probe reaction rate cannot match the production rate of the target ROS. The measured signal reflects probe kinetics, not actual cellular redox potential. Verify by:

- Performing an in vitro calibration with bolus H₂O₂ at the end of the experiment. A further signal increase indicates the probe was not saturated in vivo.

- Using a positive control (e.g., direct oxidase expression). If the probe response is slow even with known production, the limitation is confirmed.

- Switching to a faster probe (e.g., Hyper7 from roGFP2) for the same species and repeating the experiment.

Q2: I observe a lack of correlation between my redox probe signal and downstream phenotypic effects (e.g., kinase activation). How do I determine if my measurement is at fault?

A: This disconnect often arises from compartment-specific signaling not resolved by a cytosolic probe, or kinetic delays. Troubleshoot with:

- Compartment-Specific Targeting: Express your redox probe (e.g., Grx1-roGFP2) in the specific organelle of interest (mitochondria, ER).

- Temporal Analysis: Stagger your measurements. Perform high-frequency sampling immediately post-stimulus (first 30 sec) to capture rapid, transient oxidation peaks a slower probe might miss.

- Inhibitor Check: Use a scavenger (e.g., PEG-catalase) or inhibitor of the putative ROS source. If the phenotype is blocked but your probe signal is unchanged, the probe is likely not measuring the relevant pool.

Q3: My genetically encoded redox sensor shows poor dynamic range in my cell model. What optimization steps can I take?

A: Poor dynamic range exacerbates kinetic limitations. Follow this protocol:

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Range Optimization for roGFP-based Sensors

- Transduction/Transfection: Use a low MOI/low plasmid amount to avoid sensor overexpression and buffering.

- Calibration In Situ: At experiment end, permeabilize cells with 50 µM digitonin in calibration buffer (e.g., 130 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4).

- Apply Redox Buffers:

- Fully reduced state: Treat with 10 mM DTT for 5 min.

- Fully oxidized state: Treat with 10 mM H₂O₂ or 2 mM diamide for 5 min.

- Image & Calculate: Acquire images at 400 nm and 480 nm excitation (510 nm emission). Calculate the 400/480 ratio for reduced (Rred) and oxidized (Rox) states.

- Determine Dynamic Range: Dynamic Range (DR) = Rox / Rred. A DR < 5 suggests suboptimal performance. Consider:

- Checking sensor integrity via Western blot.

- Switching to a sensor with higher DR (e.g., rxRFP1 for disulfides).

- Verifying correct excitation filters.

Q4: How do I choose between a chemical probe (e.g., H2DCFDA) and a genetically encoded probe (e.g., roGFP) to minimize kinetic artifacts?

A: The choice is critical and depends on the timescale and compartment.

| Probe Type | Example | Key Kinetic Limitation | Best Use Case | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small-Molecule | H2DCFDA, MitoSOX | Irreversible reaction; consumption; ester hydrolysis kinetics; artifact generation (e.g., oxidation chain reactions). | Initial, rapid screening for broad ROS changes. Use with caution for quantification. | Use low concentrations (µM); include extensive controls (scavengers); avoid for long-term tracking. |

| Genetically Encoded (GE) | roGFP, HyPer | Reversible, but limited by the kinetics of the fused redox-active protein (e.g., Orp1 for roGFP2). Faster than most chemical probes but may still lag. | Compartment-specific, long-term, ratiometric measurement of specific redox couples (e.g., GSH/GSSG, H₂O₂). | Select the fastest variant available (e.g., HyPer7 vs. HyPer3); confirm response time in your system via calibration. |

Q5: What are the essential controls to include in every redox signaling experiment to account for kinetic confounders?

A: A mandatory control table should be implemented:

| Control Type | Purpose | Example Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Post-Experiment Full Oxidation/Reduction | Confirms probe is functional and not saturated, defining measurement limits. | Permeabilize cells, treat with 10 mM DTT (reduced) and 5 mM H₂O₂ (oxidized). Measure final ratios. |

| Source Inhibition | Validates that the measured signal originates from the intended biology. | Pre-treat with Apocynin (NOX inhibitor) or Rotenone (mitochondrial complex I inhibitor) before stimulus. |

| Scavenger Control | Confirms the signal is specific to the ROS/RNS species. | Co-apply PEG-SOD (for O₂•⁻), PEG-Catalase (for H₂O₂), or NaN₃ (for ONOO⁻). |

| Probe-Less Control | Identifies stimulus-induced autofluorescence changes. | Perform identical experiment in non-transfected/unloaded cells. |

| Kinetic Calibration | Establishes the time-lag of the probe in your specific system. | Use a photoactivatable ROS generator (e.g., KillerRed) and measure the time from activation to 90% probe response. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Addressing Kinetic Limitations |

|---|---|

| roGFP2-Orp1 / HyPer7 | Genetically encoded probes for H₂O₂. HyPer7 offers significantly faster kinetics than earlier versions, reducing measurement lag. |

| Grx1-roGFP2 | Genetically encoded probe for the glutathione redox potential (GSH/GSSG). Grx1 catalysis accelerates equilibration with the glutathione pool. |

| Aconitase-2 (mitochondrial) Activity Assay | Endogenous enzyme-based "probe" for matrix O₂•⁻. Inactivation is rapid and specific, providing a kinetic snapshot complementary to fluorescent probes. |

| PEGylated Antioxidants (PEG-Catalase, PEG-SOD) | Cell-impermeable scavengers used to distinguish intracellular from extracellular ROS events, clarifying the site of rapid signaling. |

| Photoactivatable ROS Generators (e.g., KillerRed, SOPP3) | Tools to generate a precise, rapid, and localized ROS bolus for probe kinetic calibration and pathway triggering. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | For detecting stable, endogenous redox-modified proteins (e.g., cysteine sulfenylation) as a kinetic "snapshot" that is not limited by probe turnover rates. |

| Microfluidic Perfusion Systems | Enables rapid, precise, and repeatable stimulus delivery (sub-second mixing) to synchronize cellular responses and measure true initial kinetics. |

| Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting (TCSPC) FLIM | Measures fluorescence lifetime of probes like roGFP, which is a ratiometric parameter insensitive to probe concentration, photobleaching, and excitation intensity, improving fidelity in kinetic traces. |

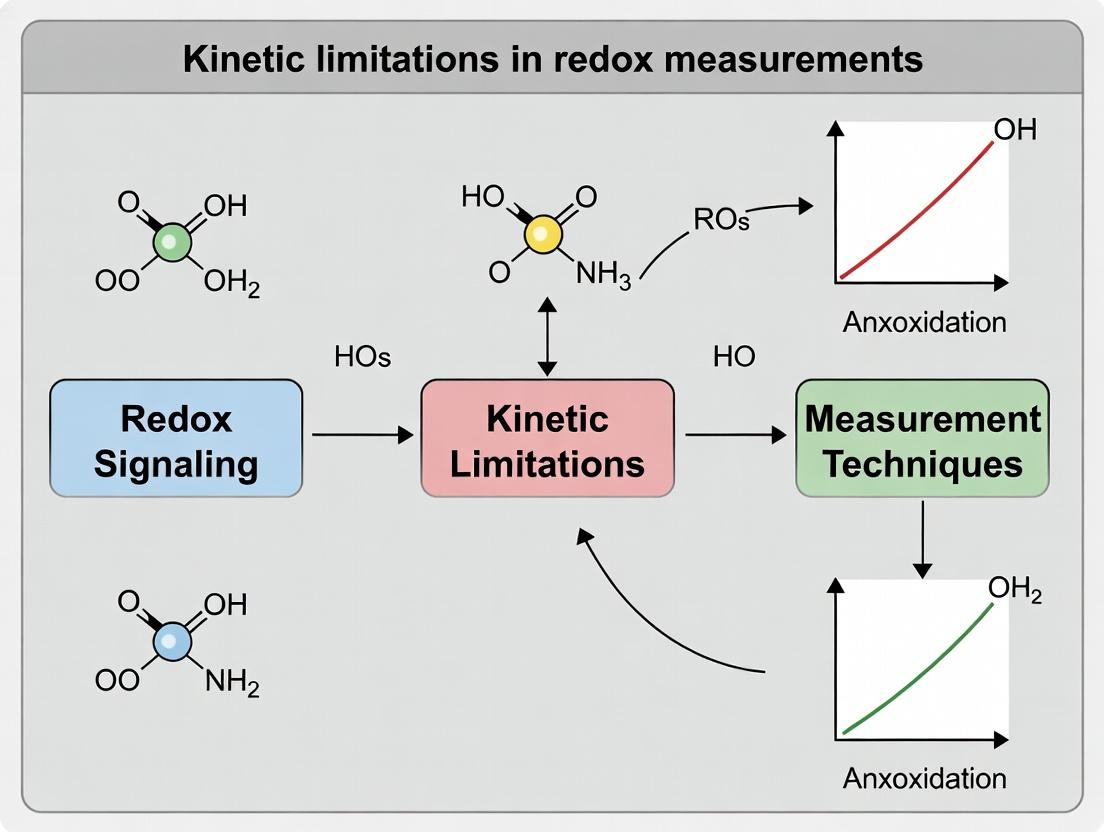

Visualizations

Title: How Kinetic Limitations Skew Data Interpretation

Title: Redox Signal Disconnect Troubleshooting Path

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ 1: My fluorescent redox probe shows a weak or unstable signal. What could be the issue?

A: Weak or unstable signals often stem from kinetic limitations. The probe's reaction rate constant (k) with the target ROS/RNS may be too slow relative to the species' diffusion limit and lifetime. For example, if the rate constant is below ~10³ M⁻¹s⁻¹ for a short-lived species like peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻), the probe will not compete effectively with its decomposition or reaction with other biomolecules. Ensure your probe's k is matched to the kinetics of the target. Check for photobleaching or improper loading protocols.

FAQ 2: How do I know if my measurement is diffusion-limited or reaction-limited?

A: Perform a concentration-dependence experiment. If the observed rate (kobs) scales linearly with probe concentration and reaches a plateau (saturates) at high concentrations, the system is moving from reaction-limited to diffusion-limited control. Compare kobs to the theoretical Smoluchowski diffusion limit (~10⁹ - 10¹⁰ M⁻¹s⁻¹ in aqueous systems). A significantly lower k_obs indicates reaction limitations.

FAQ 3: My genetically encoded sensor (e.g., roGFP, HyPer) responds slowly to a stimulus. Is this a sensor problem or a biological reality?

A: It could be both. First, consult the published rate constants for the sensor's thiol-disulfide exchange or peroxide reaction. Slow response may indicate that the local redox potential changes gradually, or that the sensor is not in kinetic equilibrium with the target couple due to compartmentalization or competing reactions. Verify sensor targeting and consider using a faster-responding small-molecule probe for comparison.

FAQ 4: How can I accurately measure the lifetime of a transient redox species in my cellular model?

A: Direct in-cell measurement is challenging. Use a combination of computational modeling and competitive kinetics experiments. Employ a panel of scavengers or probes with known, graded rate constants. The pattern of which probes "see" the species can bracket its effective lifetime. Alternatively, use rapid-mix/stopped-flow techniques in cell lysates with a fast probe like ABEL-F to establish a baseline.

Table 1: Representative Rate Constants for Redox Reactions

| Reactant A | Reactant B | Rate Constant (k, M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Approx. Lifetime of B in Cell | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂O₂ | Catalase | ~10⁷ | 1-10 ms | Diffusion-limited for enzyme |

| H₂O₂ | Typical boronate probe (e.g., PF1) | ~1 - 10 | Seconds | Reaction-limited, slow |

| H₂O₂ | Innovative fast probe (e.g., ABEL-F) | ~10⁶ | Seconds | Near diffusion-limited |

| ONOO⁻ | Typical probe (e.g., B-MitoPY1) | ~10⁵ | < 20 ms | Must compete with CO₂ |

| O₂⁻ (Superoxide) | SOD1 | ~2 x 10⁹ | Microseconds | Diffusion-limited |

| •NO | Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase | ~10⁸ | Seconds | Heme-binding, fast |

| Glutathione (GSH) | Protein sulfenic acid | 10¹ - 10³ | Variable | pH-dependent, often slow |

Table 2: Key Kinetic Parameters Influencing Measurement Fidelity

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Measurement | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Limit (k_diff) | 10⁸ - 10¹⁰ M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Ultimate speed ceiling for bimolecular reaction | Use tethered probes or enzymes. |

| Probe Reaction Rate (k) | 10⁰ - 10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹ | Determines signal amplitude and timing | Select probe with k matched to target lifetime. |

| Target Lifetime (τ) | µs to minutes | Defines the time window for detection | Increase probe concentration to outcompete decay. |

| Local Concentration | nM to mM (microdomains) | Alters observed reaction rates | Use targeted probes; interpret data cautiously. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining an Apparent Rate Constant (k_app) for a Redox Probe in Cells

Objective: To estimate the effective rate of reaction between a probe and a redox species in a cellular environment. Materials: Cells, redox probe (e.g., fluorescent dye), stimulus (e.g., bolus H₂O₂, SIN-1 for ONOO⁻), fluorescent plate reader or confocal microscope, kinetic analysis software. Method:

- Load cells with the probe according to manufacturer protocol.

- Acquire baseline fluorescence for 1-2 minutes.

- Rapidly add stimulus at a known, final concentration ([S]₀). Use rapid mixing accessories if available.

- Record fluorescence (F) time course until a plateau is reached.

- Fit the trace to a single exponential: F(t) = F₀ + ΔF(1 - e^(-kobs * t)), where kobs is the observed rate.

- Vary probe concentration ([P]₀) and repeat. Plot kobs vs. [P]₀. The slope of the linear region provides kapp.

Protocol 2: Competitive Kinetics Assay to Gauge ROS Lifetime

Objective: To bracket the effective lifetime of a transient species by competition between two probes. Materials: Cell system, two redox probes (ProbeF: fast, ProbeS: slow) with known in vitro rate constants (kF, kS), stimulus. Method:

- Divide samples into three groups: ProbeF alone, ProbeS alone, ProbeF + ProbeS together.

- Apply identical stimulus and record signal development for each group.

- Analyze initial rates (v) of signal increase for each condition.

- Calculate the concentration ratio of the species "seen" by each probe using the relation: [Species]F / [Species]S = (vF / kF[PF]) / (vS / kS[PS]).

- Interpretation: If the fast probe detects significantly more species, the lifetime is too short for the slow probe to compete. Modeling can convert this ratio into an effective lifetime estimate.

Visualizations

Title: Kinetic Competition for a Transient Redox Species

Title: Workflow for Kinetic Redox Measurement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Kinetic Redox Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fast Peroxide Probes (e.g., ABEL-F, NpF) | High rate constant (~10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹) for H₂O₂ enables detection of rapid signaling fluxes. | Requires specific imaging setups; may need custom synthesis. |

| Genetically Encoded Redox Sensors (roGFP, HyPer, rxYFP) | Rationetric, targetable probes for specific couples (e.g., GSH/GSSG, H₂O₂). | Relatively slow response (seconds). Calibration is pH-sensitive. |

| Caged ROS/RNS Donors (e.g., Caged H₂O₂, SIN-1) | Allows precise, rapid uncaging of redox species upon UV light or physiological trigger. | Uncaging kinetics and byproducts must be controlled. |

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Mimetics (e.g., MnTBAP) | Scavenges O₂⁻ with known rate constant; used as a diagnostic tool and control. | Specificity for O₂⁻ over H₂O₂ can vary. |

| Catalase & Permeative Catalase Mimetics (e.g., PEG-Catalase) | Scavenges H₂O₂; distinguishes H₂O₂-mediated events. | Large size of native catalase limits cellular access. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer/Fluorimeter | Instrument for mixing reagents in <1 ms to measure very fast reaction kinetics in vitro. | Essential for determining pure chemical rate constants (k). |

| Rapid-Perfusion Systems for Microscopy | Enables sub-second solution exchange around cells during live imaging. | Critical for applying stimuli in kinetic cellular experiments. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Our Amplex Red assay for H2O2 shows high background fluorescence, obscuring the signal. What could be the cause and how do we fix it? A: High background is often due to auto-oxidation of the Amplex Red reagent or contamination with trace metals. Ensure the assay buffer is prepared fresh with high-purity water (e.g., Milli-Q) and contains a metal chelator like DTPA (Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid, 100 µM). Protect reagents from light. Include a no-enzyme control to subtract background. Pre-incubate the plate with assay buffer for 30 minutes in the dark to assess background levels before adding your sample.

Q2: Our DAF-FM DA (for NO detection) signal is weak and inconsistent between cell passages. What are the critical steps? A: Inconsistent loading of the cell-permeable DAF-FM DA is the likely issue. Ensure cells are washed thoroughly with warm, dye-free buffer after the 30-60 minute loading incubation to completely remove extracellular esterase activity. Use a consistent cell confluence (e.g., 80%). Avoid using serum during the loading phase, as serum esterases can cleave the DA ester extracellularly, trapping the dye outside. Confirm intracellular esterase activity is normal.

Q3: During chemiluminescence detection of O2•− with Lucigenin, we observe a rapid, unsustained burst instead of a kinetic curve. Is this valid? A: A rapid, unsustained burst often indicates an artifact. Lucigenin can redox cycle, itself generating O2•−, especially at high concentrations (>10 µM). This leads to a non-physiological signal spike. Switch to a more specific probe like dihydroethidium (DHE) with HPLC validation of the 2-hydroxyethidium product, or use the cytochrome c reduction assay, and ensure your Lucigenin concentration is ≤5 µM.

Q4: Our ONOO− donor (SIN-1) doesn’t produce the expected oxidation of our target probe. What should we check? A: SIN-1 co-generates NO and O2•−, which react to form ONOO−. The kinetics are sensitive to buffer composition and pH. Perform these checks:

- pH: Use a buffer at physiological pH (7.4). ONOO− is unstable at low pH.

- Catalysts: Ensure no contaminating transition metals (use chelators).

- Donor Freshness: Prepare SIN-1 solution immediately before use. Its half-life in buffer is short (~1 hour).

- Validating Donor Activity: Always include a positive control, such as the oxidation of the fluorescent probe DHR123 (dihydrorhodamine 123) under your exact experimental conditions.

Q5: Our cell viability drops significantly when using ROS/RNS probes in live-cell imaging. How can we minimize cytotoxicity? A: Probes like DCFH-DA and DHE can generate additional ROS upon photoexcitation (photo-oxidation). To mitigate:

- Reduce laser power or exposure time.

- Use lower probe concentrations (e.g., 1-5 µM instead of 10-20 µM).

- Image cells less frequently (take time points minutes apart, not seconds).

- Consider using genetically encoded sensors (e.g., HyPer for H2O2) which are more specific and less toxic.

Table 1: Key Kinetic Parameters of Primary ROS/RNS

| Species | Typical Physiological Concentration (nM) | Approximate Half-Life | Primary Detection Method(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2O2 | 1 - 100 | ~1 ms | Amplex Red/HRP, HyPer, Boronate probes |

| NO• | 1 - 1000 | 1-5 s | DAF-FM, DAF-2, FRET sensors (e.g., geNOps) |

| O2•− | 0.01 - 1 | ~1 µs | DHE/HPLC, Cytochrome c reduction, MitoSOX |

| ONOO− | < 1 - 10 | ~10 ms | DHR123, Tyrosine nitration, specific fluorescent probes (e.g., HKGreen) |

Table 2: Comparison of Common Detection Methodologies

| Method | Target | Advantage | Limitation | Typical LOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplex Red/HRP | H2O2 | Highly sensitive, specific | Subject to interference by cellular peroxidases | ~50 nM |

| DAF-FM DA | NO | Cell-permeable, ratiometric possible | Requires intracellular esterases, not NO-specific in all contexts | ~3 nM |

| DHE/HPLC | O2•− | Specific for O2•− when validated by HPLC | Not real-time due to HPLC requirement | ~0.1 unit/ml SOD-inhibitable |

| DHR123 | ONOO−/ oxidation | Sensitive to strong oxidants | Not perfectly specific for ONOO− (reacts with •OH, CO3•−) | ~10 nM |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Specific Measurement of Extracellular H2O2 Kinetics using Amplex Red Objective: To quantify real-time, steady-state extracellular H2O2 production from cells or enzyme systems.

- Prepare fresh Amplex Red Reaction Buffer: 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 100 µM DTPA, 50 µM Amplex Red, 0.1 U/mL Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP).

- Wash cells 2x with warm, serum-free buffer. For enzymes, prepare in appropriate buffer.

- Add Amplex Red Reaction Buffer to sample in a well plate (96- or 384-well). Final volume 100 µL.

- Immediately measure fluorescence (Ex/Em = 530-560/590 nm) kinetically using a plate reader at 37°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Generate a standard curve (0-1000 nM H2O2) in parallel under identical conditions.

- Data Analysis: Subtract the no-sample control (background) fluorescence. Convert fluorescence units to [H2O2] using the standard curve. Report rate as nM/min/mg protein or per 10^6 cells.

Protocol 2: Validated Intracellular O2•− Detection using Dihydroethidium (DHE) Objective: To specifically detect intracellular superoxide formation, minimizing artifactual signals.

- Cell Loading: Load cells with 5 µM DHE in serum-free medium for 30 minutes at 37°C in the dark.

- Stimulation: After washing, add stimulus or vehicle control and incubate for desired time.

- Cell Extraction & HPLC: Lyse cells in acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Centrifuge and collect supernatant.

- HPLC Separation: Inject sample onto a C18 reverse-phase column. Use a mobile phase gradient from 37% to 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid over 20 min. Flow rate: 1 mL/min.

- Detection: Monitor fluorescence (Ex/Em = 510/580 nm for 2-hydroxyethidium (2-OH-E+), specific for O2•−; and 510/480 nm for ethidium (E+), non-specific oxidation).

- Quantification: Quantify peaks by area and normalize to protein content. Report the ratio of 2-OH-E+ to total DHE products or to E+.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: ROS/RNS Interconversion & Key Detection Points

Title: ROS/RNS Network and Detection Methods

Diagram 2: Workflow for Validated O2•− Measurement

Title: DHE/HPLC Superoxide Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Amplex Red | Fluorogenic substrate for HRP; reacts 1:1 with H2O2 to produce resorufin. | Susceptible to auto-oxidation. Use with metal chelator (DTPA). |

| Dihydroethidium (DHE) | Cell-permeable probe oxidized by O2•− to 2-hydroxyethidium (specific). | Requires HPLC/MS validation to distinguish specific product from artifacts. |

| DAF-FM DA | Cell-permeable, NO-sensitive dye. Intracellular esterases cleave DA, trapping fluorescent DAF-FM. | Measures NO-related species (N2O3), not NO directly. Sensitive to pH. |

| SIN-1 | Chemical donor that simultaneously releases NO and O2•−, forming ONOO−. | Kinetics are buffer/pH dependent. Use fresh and include an activity control. |

| PEG-SOD / PEG-Catalase | Enzymatic scavengers (polyethylene glycol conjugated) for extracellular O2•− and H2O2. | Cell-impermeable. Critical controls for identifying extracellular vs. intracellular ROS. |

| Metal Chelators (DTPA, DFX) | Bind free transition metals (Fe²⁺, Cu⁺) to prevent Fenton chemistry & probe artifacts. | Prefer DTPA over EDTA for ROS experiments; EDTA can catalyze •OH formation. |

| Specific Inhibitors (e.g., L-NAME, Apocynin, FCCP) | Pharmacologically modulate ROS/RNS producing enzymes (NOS, NADPH oxidase, mitochondria). | Verify specificity and toxicity for each cell type. Use multiple inhibitors. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Kinetic Measurements of Redox Signaling

Issue 1: Inconsistent ROS Detection Kinetics in Mitochondria

- Problem: Measured H₂O₂ burst kinetics vary widely between replicates in isolated mitochondria.

- Diagnosis: Likely due to variability in mitochondrial membrane potential or integrity of the outer membrane.

- Solution: Validate membrane potential with JC-1 or TMRM dye prior to each kinetic run. Include an integrity check using cytochrome c retention assay.

- Protocol: 1) Load mitochondria with redox probe (e.g., MitoPY1). 2) Calibrate fluorescence to nM H₂O₂ using a standard curve with glucose/glucose oxidase. 3) Initiate signal (e.g., add succinate). 4) Record fluorescence every 2 seconds for 10 mins. 5) Normalize data to mitochondrial protein content.

Issue 2: Slow or Damped Kinetics in Nuclear GSH/GSSG Ratio Measurements

- Problem: Grx1-roGFP2 probes in the nucleus show slower response times compared to cytosolic readings.

- Diagnosis: Nucleo-cytoplasmic transport limitations or improper probe targeting/nuclear export.

- Solution: Ensure probe construct has a validated nuclear localization signal (NLS, e.g., SV40). Verify nuclear confinement via confocal microscopy. Use shorter excitation pulses to minimize photobleaching in the smaller volume.

- Protocol (Nuclear Targeting Validation): 1) Transfect cells with NLS-roGFP2. 2) Stain nucleus with Hoechst 33342. 3) Perform high-resolution z-stack confocal imaging. 4) Calculate fluorescence co-localization coefficient (Pearson's >0.85 is acceptable).

Issue 3: ER Redox Potential (Eₕ) Measurements Show High Static Values, No Kinetic Response

- Problem: eroGFP or HyPer readings from the ER lumen are stable and do not reflect induced stress kinetics.

- Diagnosis: Probe is not correctly oxidized by the ER-specific system (Ero1/PDI) or is saturated.

- Solution: Confirm probe is functional via in-situ calibration with DTT (reducing) and diamide (oxidizing). Check expression levels; overexpression can swamp the native system.

- Protocol (In-situ Calibration): 1) Image baseline eroGFP ratio (405/488 nm ex). 2) Perfuse with 10mM DTT for 15 min, record. 3) Wash. 4) Perfuse with 5mM diamide for 15 min, record. A dynamic range (Rmin to Rmax) of at least 2.0 is required for kinetic studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary kinetic limitation when measuring H₂O₂ diffusion between organelles? A1: The major limitation is the effective permeability constant, which is not a simple diffusion constant. H₂O₂ must traverse lipid bilayers via aquaporins. The kinetics are governed by the local concentration gradient, the density of peroxiporins (e.g., AQP3, AQP8), and the immediate scavenging capacity (e.g., peroxiredoxins, GPx) in each compartment. This creates organelle-specific lag times and amplitude dampening.

Q2: Why do calcium-induced ROS signals from the ER show biphasic kinetics, while mitochondrial signals are often monophasic? A2: ER signals are biphasic due to sequential release from two pools: 1) A rapid, initial burst from IP3 receptor-mediated Ca²⁺ release activating NOX4 complexes. 2) A slower, sustained phase from ER stress (unfolded protein response) and secondary store-operated Ca²⁺ entry. Mitochondrial signals are typically monophasic and triggered by a single event: the uptake of released Ca²⁺ via the MCU, stimulating the TCA cycle and ETC superoxide production.

Q3: How do I synchronize kinetic measurements across different organelles in a live cell? A3: Use a universal, synchronous trigger and parallel imaging. For example:

- Trigger: Use a microfluidic system to rapidly switch media to a precise concentration of a stimulus (e.g., 100µM histamine).

- Imaging: Use a widefield or confocal microscope with multi-channel, rapid alternating excitation to simultaneously capture probes for different organelles (e.g., Mito-roGFP, eroGFP, NLS-HyPer).

Q4: What are common pitfalls in deriving rate constants from organelle-specific redox data? A4:

- Pitfall 1: Assuming first-order kinetics. Many redox reactions are pseudo-first-order or follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics due to enzyme saturation.

- Pitfall 2: Not accounting for probe kinetics. The fluorescent probe (e.g., roGFP) has its own oxidation/reduction rate, which must be significantly faster than the process being measured.

- Pitfall 3: Ignoring compartment volume. Signal amplitude is concentration-dependent; smaller volumes (e.g., nucleus) fill/empty faster than larger ones (e.g., cytosol) for identical flux rates.

Table 1: Characteristic Time Constants and Apparent Rate Constants for Redox Events

| Organelle | Redox Event / Probe | Typical Stimulus | Apparent t₁/₂ (Seconds) | Apparent Rate Constant (k, s⁻¹) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondria | H₂O₂ release (MitoPY1) | Succinate / Antimycin A | 30 - 120 s | 0.023 - 0.006 | Highly dependent on substrate and membrane potential. |

| ER Lumen | Oxidation (eroGFP) | DTT Washout / Ero1α Overexpression | 90 - 300 s | 0.0077 - 0.0023 | Limited by disulfide isomerase activity and glutathione transport. |

| Nucleus | Glutathione Redox (Grx1-roGFP2) | H₂O₂ Bolus (100 µM) | 10 - 30 s | 0.069 - 0.023 | Fast equilibration via nuclear pore; kinetics mirror cytosol unless export is blocked. |

| Cytosol | Peroxiredoxin Oxidation (Prx2-roGFP) | Local H₂O₂ Uncaging | 1 - 5 s | 0.693 - 0.139 | Extremely fast, diffusion-limited reaction. Sets baseline for cellular kinetics. |

Table 2: Key Physical and Chemical Factors Affecting Kinetics

| Factor | Mitochondria Impact | ER Impact | Nuclear Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Alkaline matrix (~8.0) accelerates thiol oxidation. | Acidic lumen (~7.2-7.4) favors protein disulfide formation. | Neutral pH (~7.2) similar to cytosol. |

| Membrane Potential | High ΔΨm (~180 mV) drives antioxidant (GSH) import via OGC. | Potential exists but less studied; impacts Ca²⁺ and ROS dynamics. | No membrane potential across nuclear envelope. |

| Primary Scavenger | Peroxiredoxin 3, Glutathione Peroxidase 1, SOD2 | Glutathione Peroxidase 7/8, Peroxiredoxin 4 | Glutathione, Thioredoxin 1, Nucleoredoxin |

| Key Regulatory Protein | Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (MPTP) | Protein Disulfide Isomerase (PDI) | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2–Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Simultaneous Kinetic Imaging of Mitochondrial and Nuclear ROS

- Objective: Measure the kinetic delay between mitochondrial ROS production and nuclear antioxidant response.

- Materials: Cells stably expressing Mito-HyPer and NLS-roGFP2-Grx1.

- Steps:

- Seed cells in glass-bottom dishes 48h prior.

- Replace media with live-cell imaging buffer (HBSS with 10mM HEPES, 5mM glucose).

- Mount dish on pre-warmed (37°C) stage with CO₂ control.

- Baseline: Acquire HyPer (488/405 ex, 520 em) and roGFP (405/488 ex, 520 em) ratio images every 10s for 2 mins.

- Stimulate: Rapidly add 200µM Tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide (tBHP) via perfusion system.

- Kinetic Acquisition: Acquire dual-ratio images every 5s for 15 mins.

- Data Analysis: Define ROIs for mitochondria and nucleus. Plot ratio over time. Calculate time-to-half-maximum (t₁/₂) for oxidation for each compartment.

Protocol B: Assessing ER Redox Kinetics During Protein Folding Stress

- Objective: Quantify the rate of ER lumen oxidation upon inhibition of protein disulfide reduction.

- Materials: HEK293T cells transfected with eroGFP, thapsigargin, DTT.

- Steps:

- Transfert cells with eroGFP-ER plasmid using standard methods.

- 24h post-transfection, treat cells with 2µM thapsigargin (in DMSO) or vehicle for 0, 15, 30, 60 mins.

- Rapidly wash cells with PBS and lyse in degassed, thiol-free buffer.

- Immediately measure eroGFP fluorescence (ex 400/490 nm, em 510 nm) in a plate reader equipped with injectors.

- In-well calibration: Inject DTT to 10mM final (Rmin), then diamide to 5mM final (Rmax).

- Calculate % oxidation = (Rsample - Rmin) / (Rmax - Rmin) * 100.

- Plot % oxidation vs. time to derive the rate of stress-induced oxidation.

Visualization: Signaling Pathways & Workflows

Diagram Title: Inter-Organelle Redox Signaling Kinetic Cascade

Diagram Title: Workflow for Comparative Organelle Redox Kinetics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration for Kinetics |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically-Encoded Redox Probes (e.g., roGFP2, HyPer, rxYFP) | Target-specific, ratiometric measurement of redox potential or ROS. | Kinetics Critical: Choose probe with reaction speed faster than biological process (e.g., roGFP2 ~1s). |

| Mito/ER/Nuclear Targeting Sequences | Directs probe to correct organelle (e.g., COX8, KDEL, SV40 NLS). | Validation Required: Mislocalization invalidates compartment-specific kinetic data. |

| Microfluidic Perfusion Systems | Enables precise, rapid, and uniform delivery of stimulants/inhibitors. | Essential for Synchronization: Reduces mixing time to <1s, enabling precise t=0. |

| Live-Cell Imaging Buffer (Phenol Red-Free) | Maintains cell health during imaging without interfering with fluorescence. | pH Stability: Use HEPES or CO₂ control to prevent pH shifts that alter probe kinetics. |

| Calibration Reagents (DTT, Diamide, H₂O₂/Glucose Oxidase) | Determines minimum (Rmin) and maximum (Rmax) ratio of ratiometric probes in-situ. | Must be performed for each experiment/field to convert ratio to quantitative metric (e.g., % oxidation). |

| Potent and Specific Inhibitors | Dissect contributions of specific pathways (e.g., Antimycin A, Rotenone, VAS2870). | Pre-incubation Time: Varies; must be optimized to achieve full block before kinetic run. |

| Rationetric Analysis Software (e.g., ImageJ/Fiji, SlideBook) | Processes time-lapse images to calculate ratio (405/488) over time for each ROI. | Batch Processing Capability is essential for analyzing multi-cell, multi-compartment datasets. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Our amperometric measurements show sudden, high-amplitude spikes. Are these hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) bursts or electrical artifacts? A: This is a common artifact. First, confirm the source:

- Motion Artifact: Ensure the working electrode is securely immobilized. Vibrations from perfusion systems or plate readers cause spike-like currents. Use vibration-damping platforms.

- Reference Electrode Instability: Check the Ag/AgCl reference electrode for air bubbles or clogged frits. Replenish the electrolyte solution.

- Solution-borne Interference: Ascorbate and certain drugs can be oxidized at similar potentials. Use selective coatings (e.g., MnO₂ nanoparticles for H₂O₂, or ascorbate oxidase) or paired electrode subtraction techniques.

Experimental Protocol for Artifact Verification:

- Title: Protocol for Distinguishing H₂O₂ Signal from Motion Artifact.

- Method:

- Set up your amperometric system (e.g., with a Pt working electrode at +0.65V vs. Ag/AgCl).

- Record a baseline in PBS with stirring.

- Test 1 (Signal): Add a bolus of known H₂O₂ (e.g., 10 µM final concentration). Note the current profile.

- Test 2 (Artifact): Gently tap the electrode holder or perfusion line to simulate vibration.

- Analysis: Compare traces. Authentic H₂O₂ addition typically shows a sharp rise followed by a gradual decay (due to diffusion/consumption). Motion artifacts are often bidirectional spikes.

Q2: We observe a slow, continuous drift in baseline current with genetically encoded redox probes (e.g., roGFP). Is this physiological or probe photobleaching/instability? A: Drift often indicates probe limitation, not biology. Key culprits:

- Photobleaching: roGFP is susceptible. Reduce excitation light intensity and frequency of acquisition. Use ratiometric measurements (400nm/490nm excitation) to correct for concentration loss.

- pH Sensitivity: roGFP's redox potential is pH-dependent. Maintain stable pH with robust buffers (e.g., 25 mM HEPES). Perform parallel calibration with dithiothreitol (DTT) and hydrogen peroxide at experimental pH.

- Expression Dynamics: Slow drift may reflect changes in probe expression/localization. Include a fluorescence protein control (e.g., GFP) to monitor expression changes independently of redox state.

Q3: Our EPR spin trapping data for superoxide is inconsistent between biological replicates. What are the critical points for sample preparation? A: Superoxide (O₂•⁻) detection is highly kinetic-limited. Consistency requires strict control of:

- Spin Trap Concentration: Use a molar excess (typically 0.5-10 mM) relative to expected O₂•⁻ flux. Pre-incubate cells/tissue with trap for 30 min.

- Oxygenation: Maintain consistent O₂ levels, as O₂•⁻ generation is oxygen-dependent. Use a tonometer or sealed vials with fixed headspace.

- Cell Number/Protein Content: Normalize results to cell count (exact) or protein concentration. Small variations cause large signal differences.

Experimental Protocol for EPR Spin Trapping:

- Title: Protocol for Consistent Superoxide Detection via EPR.

- Method:

- Sample Prep: Harvest cells by gentle scraping. Wash and resuspend in PBS containing the spin trap (e.g., 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine, CMH) and metal chelators (e.g., deferoxamine 25 µM, diethyldithiocarbamate 5 µM).

- Loading: Incubate 30-40 min at 37°C. Keep samples in the dark.

- Measurement: Transfer to a capillary tube or flat cell. Immediately record EPR spectra at room temperature using the following typical settings:

- Microwave power: 20 mW

- Modulation amplitude: 2 G

- Scan time: 60 s

- Quantification: Double-integrate the central peak of the triplet signal. Compare to a standard curve of the nitroxide radical product.

Q4: When using chemiluminescent probes (e.g., L-012), the signal saturates rapidly and does not return to baseline. How can we improve kinetic resolution? A: L-012 has a high quantum yield but non-reversible kinetics, limiting temporal resolution.

- Solution 1: Dilution & Reduced Load. Use lower probe concentrations (e.g., 50-100 µM vs. 500 µM) and fewer cells to slow the reaction and prevent rapid probe exhaustion.

- Solution 2: Use a Flow System. For cell culture, employ a perfusion chamber to continuously supply fresh probe and remove spent media, allowing continuous monitoring.

- Solution 3: Switch to Electrochemical or Genetically Encoded Probes for real-time, reversible measurements if the experimental question allows.

Table 1: Common Artifacts in Redox Signaling Measurements & Diagnostic Tests

| Artifact Type | Typical Cause | Diagnostic Experiment | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spike Noise | Mechanical vibration, loose connections | Tap test during recording in buffer. | Secure electrodes, use damping, check connections. |

| Baseline Drift | Reference electrode degradation, temperature flux. | Record in stable buffer with no cells. | Replace reference electrolyte, use temperature control. |

| Non-Specific Signal | Direct oxidation of drugs/analytes (e.g., acetaminophen). | Record signal in presence of analyte without cells. | Use selectively permeable membranes (e.g., Nafion), different potential. |

| Probe Saturation | Rapid, irreversible probe reaction (e.g., chemiluminescence). | Titrate cell number vs. signal time-to-peak. | Reduce cell number/probe concentration, use flow system. |

| pH-Confounded Signal | roGFP/pHlorin sensitivity to pH shifts. | Calibrate with DTT/H₂O₂ at different pHs. | Use stronger buffers, employ pH-insensitive controls (e.g., GFP). |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Key Redox Detection Modalities

| Method | Target | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Primary Kinetic Limitation | Artifact Prone? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometry | H₂O₂, NO | Milliseconds to seconds | ~µm (microelectrode) | Diffusion to electrode surface | High (electrical, motion) |

| Genetically Encoded (roGFP) | GSH/GSSG, H₂O₂ | Seconds to minutes | Subcellular | Thiol-disulfide exchange kinetics | Medium (pH, expression, bleaching) |

| EPR Spin Trapping | O₂•⁻, •NO | Minutes | Tissue/Organ | Spin trap reaction rate & stability | Medium (oxygen sensitivity, metal interference) |

| Chemiluminescence (L-012) | Extracellular O₂•⁻/ONOO⁻ | Seconds to minutes | Bulk solution | Probe consumption rate | High (probe exhaustion, non-specificity) |

| Borosilicate Fe²+ Sensors | Labile Fe²+ | Seconds | Subcellular | Fe²+ binding kinetics | Low (but specificity challenges exist) |

Experimental Protocol Detail

Protocol: Validating Authentic H₂O₂ Signaling with Pharmacological & Genetic Controls

- Objective: To confirm that an observed amperometric signal originates from authentic cellular H₂O₂ flux.

- Materials: Cell culture, carbon fiber microelectrode, amplifier, perfusion system, inhibitors.

- Method:

- Baseline Recording: Record current from cells in physiological buffer.

- Stimulus Application: Apply receptor agonist (e.g., growth factor) or mechanical stimulus.

- Inhibition Test (Pharmacological): Pre-treat cells with 50 U/mL PEG-catalase (extracellular scavenger) for 30 min. Repeat stimulus. Signal should be abolished.

- Source Inhibition Test: Pre-treat cells with 10 µM Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI, NADPH oxidase inhibitor) for 60 min. Repeat stimulus. Signal should be significantly reduced.

- Genetic Control (if applicable): Use cells with CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of NOX2 (or relevant NADPH oxidase). Compare signal to wild-type cells.

- Calibration: After experiments, calibrate electrode with known H₂O₂ additions (1, 5, 10 µM) to convert current (pA) to concentration (nM).

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Decision Tree for Diagnosing Redox Signal Artifacts

Diagram 2: Key Pathways in NADPH Oxidase-Dependent Redox Signaling

Diagram 3: Workflow for Kinetic-Limited Redox Experiment Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Addressing Kinetic Limitations in Redox Measurements

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration for Kinetic Studies |

|---|---|---|

| PEGylated Catalase | Extracellular H₂O₂ scavenger. Validates origin of H₂O₂ signal (membrane-impermeable). | Use to confirm signal is extracellular. Does not quench intracellular probes. |

| Cell-Permeable PEG-Catalase | Intracellular H₂O₂ scavenger. Tests for intracellular H₂O₂ mediation of effects. | Slower uptake; requires pre-incubation (1-2 hrs). Controls for probe specificity. |

| Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) | Flavoprotein inhibitor (e.g., inhibits NADPH oxidases). Identifies enzymatic O₂•⁻/H₂O₂ source. | Not entirely specific; can inhibit other flavoenzymes (e.g., NOS). Use with genetic controls. |

| Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) | Electroactive interferent control for amperometry. Oxidizes at similar potential to H₂O₂. | Use to test electrode selectivity. A signal from acetaminophen indicates need for better coating. |

| Temporally Controlled, Genetic Inducers/Suppressors (e.g., Doxycycline-inducible NOX, shRNA) | Modulates redox enzyme expression with precise timing. Overcomes limitations of slow pharmacological inhibitors. | Crucial for dissecting signaling kinetics without long-term compensatory adaptations. |

| Nitroblue Tetrazolium (NBT) / Cytochrome c | Classical, colorimetric superoxide detection. Useful for quick, endpoint validation. | Has significant kinetic limitations (slow reduction rate). Not for real-time tracking. |

| Deferoxamine (DFO) & Diethyldithiocarbamate (DETC) | Metal chelators for EPR experiments. Remove interfering metal ions that degrade spin adducts. | Essential for stabilizing superoxide-nitronyl adducts, improving signal-to-noise and reliability. |

| pH-Stable Buffers (e.g., HEPPS, Tricine) | Maintain physiological pH for probes like roGFP which are pH-sensitive. | Prevents false redox signals from pH shifts during stimulation (e.g., metabolic acidification). |

Tools and Techniques: Modern Methodologies for Capturing Fast Redox Events

Within the broader thesis on Addressing kinetic limitations in redox signaling measurements research, the development and application of genetically encoded biosensors have been transformative. These real-time kinetic probes, such as roGFP (redox-sensitive Green Fluorescent Protein) and HyPer (hydrogen peroxide sensor), allow for the dynamic, compartment-specific quantification of redox potential and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in living cells. This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in troubleshooting common experimental issues to obtain reliable, kinetically resolved data.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Sensor Expression & Localization

Q: My roGFP2 signal is cytosolic, but I targeted it to the mitochondria. What could be wrong? A: Incorrect localization often stems from insufficient or cleaved targeting sequences.

- Check: Verify your plasmid sequence for the complete mitochondrial targeting sequence (e.g., COX8 presequence). Perform immunofluorescence with organelle-specific markers to confirm co-localization.

- Solution: Use a validated plasmid from a reputable repository (Addgene). Consider using a different, stronger targeting sequence (e.g., for ER: roGFP2-KDEL).

Q: I see no fluorescence in my cells after transfection with HyPer7. A: This indicates failed expression or sensor bleaching.

- Check: Image using a standard GFP filter set first. HyPer is a cpYFP derivative. Ensure your microscope lasers/lamp is functional.

- Solution: Include a positive control (e.g., cytosolic GFP plasmid). Optimize transfection protocol (e.g., increase DNA amount, use fresh transfection reagent). For stable lines, use higher antibiotic concentration or FACS sorting.

FAQ 2: Calibration & Quantification

Q: My ratiometric calibration for roGFP is not producing two clear, maximally oxidized and reduced plateaus. A: Incomplete equilibration with calibrants is the most common cause.

- Protocol: Use a robust calibration protocol in situ:

- Image cells in initial state.

- Treat with 10 mM DTT (strong reductant) in imaging buffer for 5-10 min. Image for fully reduced state.

- Wash and treat with 1-5 mM H₂O₂ or 100 µM Diamide (oxidant) for 5-10 min. Image for fully oxidized state.

- Ensure permeabilization with 0.05% Digitonin if calibrants are not cell-permeant.

- Solution: Increase treatment time and concentration. Verify pH of calibration buffers, as extremes can affect fluorescence. Use freshly prepared DTT and H₂O₂.

Q: The dynamic range of my HyPer sensor seems low in my experimental system. A: Dynamic range can be affected by basal H₂O₂ levels or sensor saturation.

- Check: Perform a positive control by adding a bolus of H₂O₂ (100 µM - 1 mM) at the experiment end. If the ratio increases significantly, your basal signal may be already oxidized.

- Solution: Express the sensor at lower levels to avoid buffering the signal. Work in low serum/media during imaging to reduce external ROS sources. Use the appropriate HyPer variant (e.g., HyPer7 has faster kinetics and reduced pH sensitivity).

FAQ 3: Data Interpretation & Artifacts

Q: My roGFP ratio changes during a treatment, but I'm unsure if it's due to redox changes or pH artifacts. A: roGFP2 is pH-sensitive at extremes. This must be controlled.

- Experimental Control: Perform parallel experiments with a pH-only sensor like pHluorin or SypHer (a pH-sensitive, redox-insensitive HyPer variant).

- Solution: If a pH change coincides with your treatment, use a redox sensor with reduced pH sensitivity (e.g., roGFP2-Orp1, Grx1-roGFP2) or perform experiments in pH-clamped buffers.

Q: The kinetics of the HyPer signal are slower than expected based on the literature. A: This often relates to sensor expression level or cellular antioxidant capacity.

- Check: Ensure you are not overexpressing the sensor, which can buffer H₂O₂ and slow observed kinetics.

- Solution: Generate stable cell lines with lower expression via FACS. Use the newer HyPer7 variant, which has faster oxidation/reduction kinetics (~60 s halftime) compared to older versions.

Key Sensor Properties & Data

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Genetically Encoded Redox Sensors

| Sensor Name | Target | Excitation/Emission Peaks (nm) | Readout Mode | Dynamic Range (Ratio Ox/Red) | Typical Response Time | Key Interferant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP2 | Glutathione redox potential (EGSSG/2GSH) | 400/510 & 490/510 | Ratiometric (400/490 nm exc.) | ~5 - 10 (in vitro) | Oxidation: seconds-minutes | pH (<6.5, >8.5) |

| Grx1-roGFP2 | Glutathione redox potential (via Glutaredoxin) | 400/510 & 490/510 | Ratiometric (400/490 nm exc.) | ~5 - 8 (in vivo) | ~5 minutes (equilib.) | Specific for GSH/GSSG |

| HyPer (e.g., HyPer7) | H₂O₂ | 420/516 & 500/516 (for cpYFP) | Ratiometric (420/500 nm exc.) | ~3 - 5 (in vivo) | Oxidation: <1 min; Reduction: ~minutes | pH (cpYFP is pH-sensitive) |

| rxYFP | Thioredoxin redox potential | 514/527 | Intensity-based | N/A | Minutes | Less specific; general thiol redox |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Experiment | Example/Brief Protocol Note |

|---|---|---|

| DTT (Dithiothreitol) | Strong reducing agent for roGFP calibration. | Use at 10 mM in imaging buffer for 5-10 min. Freshly prepared. |

| Diamide | Thiol-specific oxidant for roGFP calibration. | Use at 100 µM - 2 mM for 5-10 min. Less likely than H₂O₂ to cause non-specific damage. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Physiological oxidant; used for calibration and stimulation. | For HyPer calibration, use 100 µM - 1 mM. Aliquot and store frozen; avoid repeated freeze-thaw. |

| Digitonin | Mild detergent for cell permeabilization during calibration. | Use at 0.005-0.05% in calibration buffer to allow entry of non-permeant reagents (e.g., GSSG). |

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) | Antioxidant precursor; negative control for redox perturbations. | Pre-treat cells with 1-5 mM NAC for 1-2 hrs to dampen endogenous ROS signals. |

| Butylated Hydroxyanisole (BHA) | Synthetic antioxidant; positive control for reducing environment. | Use at 100 µM to reduce cellular ROS. Can affect multiple pathways. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1:In SituCalibration of roGFP for Absolute Redox Potential Calculation

Objective: To convert ratiometric roGFP data into absolute glutathione redox potential (EGSSG/2GSH). Materials: Cells expressing roGFP, imaging buffer, 10 mM DTT, 5 mM H₂O₂ or 2 mM Diamide, 0.05% Digitonin, fluorescence microscope capable of rapid excitation switching. Steps:

- Image Baseline: Acquire ratio (F405/488) images of cells in standard imaging buffer.

- Reduce: Incubate cells in imaging buffer + 0.05% Digitonin + 10 mM DTT for 10 min. Acquire ratio images (Rmin).

- Wash: Rinse cells 2x with Digitonin-free imaging buffer.

- Oxidize: Incubate cells in imaging buffer + 0.05% Digitonin + 5 mM H₂O₂ (or 2 mM Diamide) for 10 min. Acquire ratio images (Rmax).

- Calculate: Determine the degree of oxidation (OxD) for each time point: OxD = (R - Rmin) / (Rmax - Rmin).

- Convert to EGSSG/2GSH: Use the Nernst equation: E = E0 - (RT/nF) ln([GSH]²/[GSSG]). For roGFP2, E0 is approximately -280 mV. With known total glutathione pool, E can be derived from OxD.

Protocol 2: Measuring H₂O₂ Flux with HyPer

Objective: To dynamically measure localized changes in H₂O₂ concentration. Materials: Cells expressing HyPer (e.g., HyPer7), phenol-red free culture medium, 100 µM - 1 mM H₂O₂ for positive control, stimulus of interest (e.g., Growth Factors, Drugs). Steps:

- Setup: Culture cells in glass-bottom dishes. Switch to pre-warmed, phenol-red free imaging medium 30 min before experiment.

- Acquisition: Set up time-lapse imaging with dual-excitation (ex: 420/10 nm and 500/10 nm, em: 516/10 nm). Acquire images every 30-60 seconds.

- Baseline: Record baseline ratio for 5-10 minutes to establish stability.

- Stimulate: Add your experimental stimulus directly to the medium without moving the dish. Continue acquisition.

- Control: At the experiment end, add a bolus of H₂O₂ (final 100 µM - 1 mM) to record the maximum ratio change for normalization.

- Analysis: Calculate the 420/500 nm ratio over time. Normalize data as (R - Rbaseline) / (Rmax H2O2 - Rbaseline) or report as ratio change (ΔR/R0).

Visualizations

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FSCV-Specific Issues

Q: I observe excessive charging current and a unstable baseline during my FSCV experiments, obscuring faradaic signals. What could be the cause?

A: This is typically due to a compromised electrode or poor electrical connections. First, ensure all connections (headstage, reference, working electrode) are clean and secure. Re-polish or re-carbon your microelectrode. If the problem persists, the issue may be with the Ag/AgCl reference electrode; check its chloride coating and replate if necessary. Ensure your electrolyte solution is properly grounded.

Q: My catecholamine oxidation peak potential shifts significantly between calibration and in-vivo measurement. How should I address this?

A: This is a common challenge when moving from a simple buffer to a complex biological milieu (e.g., brain tissue). The shift is often due to changes in local pH, ionic strength, or protein adsorption. To address kinetic limitations in signaling measurements, always perform in-situ or post-experiment calibration in a solution that closely mimics the experimental environment (e.g., artificial cerebrospinal fluid). Do not rely solely on pre-experiment buffer calibrations.

Q: The sensitivity of my carbon-fiber microelectrode has dropped dramatically. How can I restore it?

A: Follow this electrode reconditioning protocol: 1) Sonicate in isopropyl alcohol for 5 minutes. 2) Rinse thoroughly with deionized water. 3) Electrochemically clean by applying a triangular waveform (e.g., -0.4V to +1.3V vs. Ag/AgCl at 400 V/s) in 0.5 M PBS for 10-15 minutes until the cyclic voltammogram stabilizes. 4) Perform a final calibration.

MEA-Specific Issues

Q: I am detecting electrochemical interference (cross-talk) between adjacent microelectrodes on my MEA during simultaneous voltammetry. How can I mitigate this?

A: Cross-talk is a kinetic limitation for high-density, parallel measurements. Implement time-division multiplexing where adjacent electrodes are scanned at slightly offset times. Alternatively, use a "checkerboard" pattern, scanning only non-adjacent electrodes simultaneously. Ensure your instrument's ground paths are optimal and consider using a bipotentiostat with independent control for critical channels.

Q: My MEA recordings show inconsistent sensitivity across electrodes. What is the standard quality control procedure?

A: Perform a uniformity check before each experiment. Immerse the MEA in a standard solution (e.g., 1 µM dopamine in PBS). Run identical CV scans on all electrodes and tabulate the peak oxidation current. Electrodes with a sensitivity deviation >15% from the array mean should be disabled or noted for data exclusion. This step is critical for generating reliable, spatially resolved signaling data.

Q: How do I differentiate between a true redox signal and a pH shift on an MEA?

A: This is a key challenge in interpreting in-vivo signaling. The primary method is via voltammetric "fingerprinting." Collect the full cyclic voltammogram at each electrode. A pH change typically causes a concerted, proportional shift in both oxidation and reduction peaks. A true redox event (e.g., dopamine release) shows a characteristic shape with distinct peak separations. Using principal component analysis (PCA) with training sets for pH and your analyte can automate this discrimination.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In-Vivo FSCV for Transient Dopamine Detection

- Electrode Preparation: Pull a single carbon-fiber (7 µm diameter) into a glass capillary, seal with epoxy, and bevel at 45° to a tip length of ~50-100 µm.

- Electrochemical Conditioning: Insert the electrode into PBS. Apply a triangle waveform (-0.4 V to +1.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 400 V/s, 60 Hz) for 15 min until stable.

- Calibration: Transfer to a stirred solution of 1 µM dopamine in PBS. Apply the experimental waveform (e.g., -0.4 V to +1.3 V and back, 400 V/s, 10 Hz). Record the average oxidation current at the peak potential (~0.6-0.7 V). Calculate sensitivity (nA/µM).

- In-Vivo Implantation: Stereotaxically implant the working electrode alongside a reference and bipolar stimulating electrode in the target region (e.g., striatum).

- Data Acquisition: Apply the FSCV waveform continuously. Use electrical stimulation (e.g., 60 pulses, 60 Hz, 300 µA) to evoke release. Record the voltammetric current in 3D (time, potential, current).

- Data Analysis: Use background subtraction to isolate faradaic current. Identify analytes by their characteristic CV "fingerprint." Convert current to concentration using the pre-calibration sensitivity.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening of Redox-Modulating Compounds with MEAs

- MEA Pre-treatment: Sterilize the MEA (e.g., 16-channel Pt microelectrode) with 70% ethanol and UV light. Coat with a biocompatible layer like Nafion to enhance selectivity for cations.

- Cell Seeding: Seed the MEA chamber with the target cell line (e.g., SH-SY5Y or primary neurons) at a density of 50,000-100,000 cells per well. Culture for 5-7 days to allow adhesion and network formation.

- Experimental Setup: Place the MEA in a Faraday cage on a heated stage (37°C). Connect to a multi-channel potentiostat. Add pre-warmed recording medium.

- Baseline Recording: Perform amperometric or FSCV recordings at all electrodes simultaneously for 10 minutes to establish a stable baseline.

- Compound Addition: Using a microfluidic perfusion system or careful pipetting, introduce the test compound (e.g., a drug candidate) at a range of concentrations (e.g., 1 nM, 10 nM, 100 nM).

- Signal Acquisition & Analysis: Record continuously for 30-60 minutes post-addition. Analyze parameters such as: amplitude of oxidative events, frequency of transient signals, and changes in resting current. Compare to vehicle controls to identify compounds that significantly alter redox signaling kinetics.

| Technique | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Primary Analytes | Key Limitation for Kinetic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) | <100 ms | Single point (µm scale) | Catecholamines, serotonin, pH, O2 | Limited chemical identification in complex mixtures; surface fouling. |

| Microelectrode Arrays (MEA) - Amperometry | <10 ms | Multipoint (mm to µm scale) | Any electroactive species (single potential) | No chemical identification; cross-talk between electrodes. |

| MEA - Multiplexed FSCV | <500 ms per channel | Multipoint (mm to µm scale) | Catecholamines, serotonin | Trade-off between number of channels and scan rate per channel. |

| Artifact/Symptom | Likely Cause | Diagnostic Test | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drifting Baseline | Temperature fluctuation, unstable reference electrode, electrode fouling. | Record in temperature-controlled buffer without analyte. | Allow system to thermally equilibrate; replace/plate reference electrode; clean/polish working electrode. |

| Broad, ill-defined peaks | Slow scan rate, high solution resistance, damaged electrode. | Check electrode CV in standard ferricyanide solution. | Increase scan rate if possible; use higher ionic strength buffer; re-prepare microelectrode. |

| Spontaneous current spikes | Electrical noise, bubble formation on electrode, cellular debris. | Observe if spikes correlate with equipment (pumps, lights) or are random. | Improve Faraday cage grounding; degas solutions; filter culture media; use a vibration isolation table. |

Visualizations

Figure 1: In-Vivo FSCV Experimental Workflow

Figure 2: Key Kinetic Steps in Redox Signaling at a Microelectrode

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes | The working electrode. Provides a biocompatible, high-surface-area, conductive surface for electron transfer. | Single 7µm cylindrical fiber or 33µm disc. Choice affects sensitivity and spatial resolution. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential against which the working electrode voltage is controlled. | Can be a traditional cell or a chlorinated silver wire. Stability is critical for reproducible potentials. |

| Fast Potentiostat | Applies the voltage waveform and measures the resulting nanoampere-scale current with high temporal fidelity. | Must be capable of high scan rates (>300 V/s) for FSCV and have low-noise specifications. |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Polymer | Cation-exchange coating applied to electrode surface. Repels anions (e.g., ascorbate) to improve selectivity for cationic neurotransmitters. | Typically applied by dip-coating. Thickness must be optimized to avoid hindering analyte diffusion kinetics. |

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | Physiologically relevant electrolyte solution for in-vitro and in-vivo calibration and experiments. | Contains NaCl, KCl, NaHCO3, CaCl2, MgCl2, buffered to pH 7.4. |

| Dopamine Hydrochloride | Primary standard for calibration and positive control. A model catecholamine for redox signaling studies. | Prepare fresh daily in 0.1M HClO4 or aCSF to prevent oxidation. Used to determine electrode sensitivity. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This technical support center addresses common issues encountered when using advanced microscopy techniques to study the kinetics of redox signaling.

FAQ 1: My TIRF images show uneven illumination or aberrantly high background, obscuring membrane-proximal redox events.

- Answer: This is typically caused by improper alignment of the laser beam or contamination on optical components. Ensure the incident angle is precisely calibrated to achieve total internal reflection. Clean the objective lens and the sample-facing side of the TIRF prism/slider. Verify that the evanescent field penetration depth (typically 60-150 nm) is appropriate for your cell type; excessive depth increases background from cytoplasmic fluorescence.

FAQ 2: FLIM measurements for NAD(P)H or redox biosensors exhibit low photon counts and poor fit reliability.

- Answer: Low signal is the primary challenge for FLIM. Increase laser power within the limits of photobleaching and cellular toxicity. Use a high-numerical-aperture (NA >1.45) objective to collect more photons. Ensure your biosensor (e.g., roGFP, HyPer) is expressed at optimal levels—too low gives poor signal, too high causes buffering artifacts. For TCSPC systems, confirm that the count rate does not exceed 5% of the laser repetition rate to avoid pile-up distortion.

FAQ 3: Ratiometric imaging signals (e.g., from roGFP) are noisy, hindering kinetic analysis of redox transients.

- Answer: Noise in ratiometric imaging often stems from sequential acquisition of the two excitation channels. Implement rapid alternating excitation (≤ 100 ms switch time) to minimize temporal mismatch. Use a high-sensitivity, low-read-noise camera (sCMOS or EMCCD). Apply a gentle temporal binning (e.g., 3-frame moving average) post-acquisition, ensuring it does not obscure the kinetic event of interest (e.g., a ROS burst).

FAQ 4: Correlative TIRF-FLIM experiments show temporal drift between modalities.

- Answer: Synchronization is key. Use hardware-triggered acquisition controlled by a single master software (e.g., Micro-Manager) to align TIRF and FLIM data streams temporally. Introduce fiducial markers (immobile fluorescent beads) in the sample to correct for spatial drift post-hoc. Regularly calibrate the delay times between system components.

FAQ 5: My biosensor response is sluggish and does not capture expected rapid redox kinetics.

- Answer: This may be a biosensor limitation, not microscopy. Verify the kinetics of your biosensor (e.g., roGFP oxidation/reduction in vitro half-times). Ensure experimental conditions (e.g., temperature at 37°C, proper perfusion) do not limit the reaction. Consider using faster biosensors (e.g., Mrx1-roGFP2 for H2O2) and confirm expression is targeted to the correct subcellular compartment.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Advanced Modalities for Redox Kinetics

| Technique | Temporal Resolution | Key Measurable Parameter | Advantage for Redox Signaling | Typical Kinetics Measurable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIRF | 10-1000 ms | Membrane proximity, localization | Isolates membrane-initiated signaling (e.g., receptor oxidation) | Fast recruitment (>1 s) |

| FLIM | 0.2-2 s (TCSPC) | Fluorescence lifetime (τ), sensitive to microenvironment | Rationetric, independent of probe concentration; detects molecular interactions | Lifetime shifts due to oxidation (ns scale) |

| Ratiometric Imaging | 50-500 ms | Emission or excitation ratio | Internally referenced, cancels out artifacts from focus drift | ROS bursts (sub-second to minutes) |

| Correlated TIRF-FLIM | 1-5 s | Co-localization + lifetime changes | Links spatial localization with conformational changes | Slower redox modifications (>5 s) |

Table 2: Common Redox Biosensors & Imaging Parameters

| Biosensor | Redox Species | Excitation/Emission (nm) | Modality of Choice | Dynamic Range (Ratio) | Reported Response Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP2-Orp1 | H₂O₂ | 400/490; 480/510 | Ratiometric (Ex) TIRF/FLIM | ~8-10 fold | ~30-60 s |

| HyPer7 | H₂O₂ | 490/516; 405/516 | Ratiometric (Ex) TIRF | ~5 fold | <1 s |

| Grx1-roGFP2 | Glutathione redox potential (E_GSSG) | 400/490; 480/510 | Ratiometric (Ex) FLIM | ~6 fold | ~3-5 min |

| Mito-roGFP2 | Mitochondrial H₂O₂ | 400/510; 480/510 | Ratiometric (Ex) FLIM | ~5 fold | ~1-2 min |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: TIRF Setup for Imaging Growth Factor-Induced Redox Signaling at the Membrane

- Cell Preparation: Plate cells on high-quality, #1.5H glass-bottom dishes. Transfect with a membrane-targeted redox biosensor (e.g., Lyn-tagged roGFP).

- TIRF Calibration: Using the alignment laser, adjust the beam to achieve a clean, elliptical profile at the objective's back focal plane. Fine-tune the incident angle until background from the cytosol is minimized.

- Acquisition: Set up sequential or alternating excitation at 405 nm and 488 nm. Use exposure times of 50-200 ms per channel. Maintain focus using a hardware autofocus system.

- Stimulation: Perfuse cells with pre-warmed growth factor (e.g., EGF at 100 ng/mL) while imaging continuously. Record for at least 5 minutes post-stimulation.

- Analysis: Calculate the 405/488 nm ratio per pixel over time. Identify regions of interest (ROIs) at the membrane to generate kinetic traces.

Protocol 2: FLIM Measurement of NAD(P)H during Metabolic Oscillations

- Sample Preparation: Use wild-type or relevant mutant cells. Do not transfect; rely on endogenous NAD(P)H autofluorescence. Maintain cells in imaging medium without phenol red.

- FLIM Setup (TCSPC): Use a two-photon excitation at 740 nm or a UV laser at 355 nm. Set repetition rate to 20 MHz. Adjust the gain and discriminator levels on the detector to optimize the photon counting rate.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire timestamps until 1000-2000 photons per pixel are collected, typically requiring 1-5 seconds per frame. Acquire a time-series over 10-20 minutes.

- Lifetime Fitting: Fit the decay curves to a double-exponential model using software (e.g., SPCImage, FLIMfit). Report the mean fluorescence lifetime (τ_m) or the relative contributions of free (short τ) and protein-bound (long τ) NAD(P)H.

- Correlation: Correlate shifts in τ_m with simultaneous ratiometric measurements from a redox biosensor like roGFP.

Visualization Diagrams

Title: TIRF Workflow for Membrane Redox Kinetics (100 chars)

Title: FLIM & Ratiometric Correlation Workflow (100 chars)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| roGFP2-Orp1 Plasmid | Genetically encoded biosensor for specific detection of H₂O₂ with high dynamic range. |

| HyPer7 Plasmid | Ultrasensitive, fast-responding genetically encoded biosensor for H₂O₂. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Strong reducing agent used for in situ calibration of redox biosensors to define the fully reduced state. |

| Diamide | Thiol-oxidizing agent used for in situ calibration to define the fully oxidized state of biosensors. |

| #1.5H Coverslips/Dishes | High-precision glass optimized for TIRF microscopy, ensuring consistent evanescent field depth. |

| Poly-D-Lysine | Coating reagent to improve adherence of cells to glass surfaces for stable TIRF imaging. |

| Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with 10 mM HEPES | Common imaging medium without phenol red, maintaining pH and ion balance during live-cell experiments. |

| NAD(P)H (Sodium Salt) | Pure chemical for generating calibration curves or testing FLIM system response. |

| Rothenium-based FLIM reference standard | Fluorophore with a known, stable lifetime for daily calibration and validation of the FLIM system. |

Stopped-Flow and Rapid-Mixing Techniques for In Vitro Kinetic Analysis

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: We observe poor signal-to-noise ratios in our stopped-flow absorbance measurements of cytochrome c reduction. What are the primary causes and solutions? A: Common causes are air bubbles, contaminant quenching, or inadequate mixing. First, ensure thorough degassing of all buffers and reagent solutions. Perform a "water shot" test to check for air bubbles in the drive syringes and observation chamber. Clean all fluidic paths with 0.5 M NaOH followed by copious distilled water to remove any protein or fluorescent contaminants. Verify that the dead time of your instrument (typically 1-3 ms) is appropriate for your expected reaction rates; if your reaction is too fast, consider a continuous-flow instrument. Increase protein concentration if possible, but ensure it remains within the linear range of the detector.

Q2: Our rapid-quench flow experiment shows inconsistent product yield at very short time points (<10 ms). How can we improve reproducibility? A: Inconsistency at sub-10 ms time points typically indicates issues with the quenching process or timing. Calibrate the delay line length meticulously using a standard reaction with a known rate constant (e.g, hydrolysis of 2,4-dinitrophenyl acetate). Ensure the quenching reagent is in at least a 5-fold molar excess and that mixing with the quench is complete and instantaneous. Check for wear on the mechanical stop syringe or pneumatic actuators, as mechanical lag can cause timing drift. Pre-incubate both reactant syringes at the same precise temperature (±0.1°C) before the experiment.

Q3: When measuring fast electron transfer kinetics, we get artifacts suggesting multiple kinetic phases. Are these real or instrumental? A: They may be instrumental. First, perform a "no mix" control by loading the same solution into both syringes; any observed signal change is an artifact (e.g., from shear or pressure changes). Next, perform a "double-mix" experiment to distinguish sequential steps. A common artifact is "teething," where incomplete mixing in the first few milliseconds creates a transient gradient. Verify that the Reynolds number in the mixer is >2000 to ensure turbulent flow. If phases persist, they may be real, indicative of conformational gating or multiple redox-active sites.

Q4: How do we determine the precise dead time of our stopped-flow instrument for a critical kinetic model? A: The dead time must be determined experimentally using a standard reaction with a known second-order rate constant under your specific conditions (buffer, temperature). The most common standard is the reduction of 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) by ascorbic acid at pH 4.0. Monitor the absorbance decrease at 600 nm. By varying concentrations and using the known rate constant (≈ 1.2 x 10^4 M^-1 s^-1 at 15°C), you can extrapolate the observed initial rate back to the true start time, defining the dead time. Perform this calibration monthly.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Loss of Pressure / Incomplete Drive Syringe Displacement. Symptoms: Short, truncated signals; inconsistent shot volumes; error messages from the pneumatic drive. Diagnostic Steps:

- Check for leaks in the fluid path by performing a drive test with water onto a weigh scale.

- Inspect O-rings and seals on drive pistons and syringes for wear or cracking.

- Verify the stop syringe is not bent or obstructed. Solutions: Replace all worn seals. Lubricate seals with manufacturer-recommended grease. Ensure the stop syringe is correctly aligned. Check that the gas drive pressure is set to the recommended level (typically 80-120 psi).

Problem: Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) Saturation or Unstable Fluorescence Baseline. Symptoms: Signal peaks then flatlines; high baseline noise; drifting baseline between shots. Diagnostic Steps:

- Test with a stable fluorescent standard (e.g., quinine sulfate).

- Check for ambient light leaks.

- Monitor high voltage supply for the PMT. Solutions: Always start with the PMT high voltage at its minimum. Use neutral density filters if the signal is too strong. Ensure the observation chamber is fully shrouded. Allow the instrument and lamp (if Xenon arc) to warm up for at least 30 minutes for stability. Replace the lamp if it is near the end of its rated life.

Problem: Cross-Contamination Between Experiments. Symptoms: Non-zero baseline; evidence of reaction in control shots. Diagnostic Steps: Run a strong cleaning solution (e.g., 1% Hellmanex) followed by water, then observe the signal for residual absorbance/fluorescence. Solutions: Implement a rigorous cleaning protocol: 1) Flush with experimental buffer (3x volume of fluidics). 2) Use a "cleaning shot" of 10% ethanol or 0.5 M NaOH between different protein samples. 3) For stubborn contaminants, use a pepsin/HCl solution for protein deposits. Always include a buffer-versus-buffer control shot at the start of any experiment series.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Calibration Reactions for Stopped-Flow & Rapid-Mixing Instruments

| Reaction | Detection Method | Typical Conditions | Known Rate Constant (k) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCPIP + Ascorbate | Abs @ 600 nm | pH 4.0, 15°C | 1.2 x 10^4 M⁻¹ s⁻¹ | Dead Time Determination |

| NBD-Chloride + Butylamine | Fluor. (Ex470/Em540) | pH 9.0, 25°C | ~50 M⁻¹ s⁻¹ | Mixing Efficiency Check |

| Fe(EDTA)⁻ + H₂O₂ | Abs @ 260 nm | pH 7.0, 25°C | 5 x 10^3 M⁻¹ s⁻¹ | Peroxide Kinetics Standard |

| Catalase + H₂O₂ | O₂ Electrode / Abs 240 nm | pH 7.0, 20°C | k_cat ≈ 10^7 s⁻¹ | Very Fast Enzyme Check |

Table 2: Impact of Common Issues on Measured Kinetic Parameters in Redox Signaling Studies

| Artifact / Issue | Typical Effect on k_obs | Effect on Amplitude | Diagnostic Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incomplete Mixing | Biphasic, initial k too high | Unreliable | Vary flow velocity; use standard reaction |

| Photobleaching | Apparent first-order decay | Decreases over shots | Run without mixing (light only) |

| Enzyme Inactivation | k_obs decreases with shot # | Decreases with shot # | Plot signal amplitude vs. shot number |

| Contaminant Quenching | k_obs artificially low | Lower than expected | Clean system; use fresh reagents |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Instrument Dead Time via DCPIP Reduction. Objective: To empirically measure the dead time (τ) of a stopped-flow spectrophotometer. Reagents: 50 µM 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP) in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.0. 10 mM L-ascorbic acid in the same buffer (prepare fresh). Procedure:

- Load one drive syringe with DCPIP solution and the other with ascorbic acid solution.

- Thermostat both syringes and the observation cell to 15.0°C.

- Set detector to monitor absorbance at 600 nm.

- Perform a minimum of 5 shots, averaging the traces.

- Fit the exponential phase of the averaged trace to obtain the observed rate constant (k_obs) at these concentrations.

- The known second-order rate constant k (1.2 x 10^4 M⁻¹ s⁻¹) allows calculation of the expected initial velocity: vi = k [DCPIP]0 [Asc]_0.

- Extrapolate the initial tangent of the observed curve back to the initial absorbance (A0). The time difference between the trigger point (t=0) and the intersection of the tangent with A0 is the dead time (τ).

Protocol 2: Rapid-Quench Flow Kinetics for Phosphotransfer in a Kinase Cascade. Objective: To measure the rate of protein phosphorylation in a redox-regulated MAPK pathway. Reagents: Activated upstream kinase (MEK1), downstream kinase substrate (ERK2), ATP mix (with [γ-³²P]ATP), quench solution (5% TCA, 2% SDS, 100 mM NaPPi). Procedure:

- Prepare Syringe A: 2x MEK1 in reaction buffer.

- Prepare Syringe B: 2x ERK2 + 2x ATP mix (including tracer).

- Set the delay line to achieve the desired first time point (e.g., 20 ms).

- Initiate mixing. The reaction proceeds in the delay line for the set time before being expelled and mixed 1:1 with the quench solution from Syringe C.

- Collect the quenched sample and process for scintillation counting or SDS-PAGE/autoradiography.

- Repeat for a series of delay times (e.g., 20 ms, 50 ms, 100 ms, 200 ms, 500 ms, 1 s, 2 s).

- Plot product formed (pmol) vs. time and fit to the appropriate kinetic model.

Mandatory Visualization

Stopped-Flow Experiment Workflow

Simplified Redox Signaling Relay

Troubleshooting Low Signal-to-Noise

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Stopped-Flow/Rapid-Mixing | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Buffer Systems (e.g., Glucose/Glucose Oxidase, Sparging with Argon) | Removes O₂ to study anaerobic redox reactions or prevent oxidase side-reactions. | Must be coupled with sealed syringes; check for gas bubble formation. |