NADPH and NADH: Mastering the Redox Code in Health, Disease, and Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the distinct yet interconnected roles of NADPH and NADH in cellular redox biology.

NADPH and NADH: Mastering the Redox Code in Health, Disease, and Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the distinct yet interconnected roles of NADPH and NADH in cellular redox biology. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational knowledge on biosynthesis, compartmentalization, and core functions in energy metabolism, antioxidation, and reductive biosynthesis. The content delves into advanced methodologies for real-time monitoring of these coenzyme pools, addresses the pathological consequences of their dysregulation in aging and cancer, and evaluates emerging therapeutic strategies targeting their metabolism. By integrating foundational principles with cutting-edge applications and comparative analysis, this review serves as a critical resource for navigating the complexities of redox biology in drug discovery and development.

The Redox Essentials: Defining the Distinct Roles of NADH and NADPH

Chemical Structures and Fundamental Redox Properties

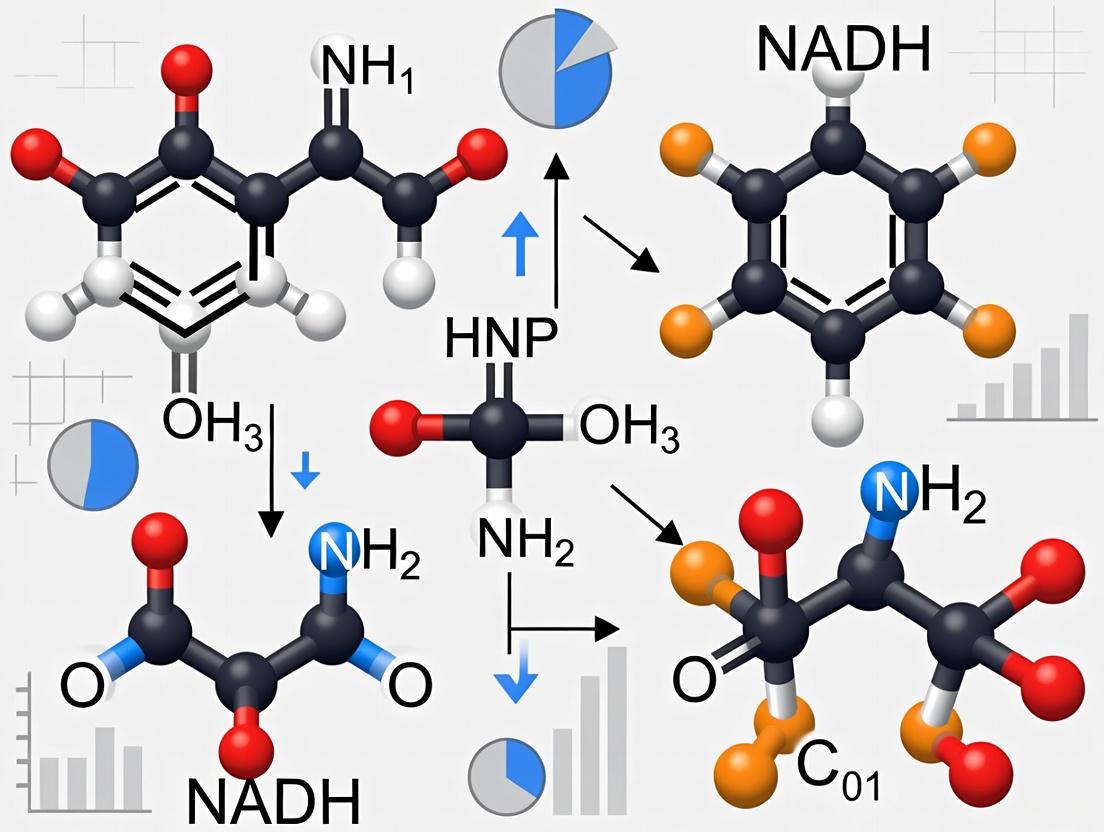

The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide cofactors, NAD(H) and NADP(H), are fundamental to cellular redox biochemistry, serving as essential electron carriers in all living organisms [1]. The NAD pool is primarily engaged in regulating energy-producing catabolic processes, such as glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [1] [2]. In contrast, the NADP pool is crucial for anabolic biosynthesis and maintaining the cellular antioxidant defense system [1] [2]. These cofactors exist in interconvertible oxidized and reduced forms: NAD+ accepts electrons to become NADH, while NADP+ accepts electrons to become NADPH [3]. This redox interchange represents a central biochemical mechanism for transferring reducing equivalents between metabolic pathways. The chemical basis of this electron transfer involves a hydride ion transfer to the nicotinamide ring of NAD+ or NADP+, which serves as an electron sink [3]. Understanding the structural characteristics and redox properties of these molecules is crucial for interpreting their roles in cellular metabolism, energy homeostasis, and redox signaling [1] [4].

Chemical Structures and Redox Reactions

Fundamental Structural Characteristics

NAD+ and NADP+ are derivatives of nicotinic acid or nicotinamide [3]. The core structure of both molecules consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups: one nucleotide contains an adenine base, and the other contains a nicotinamide base [3]. The critical structural distinction between NAD+ and NADP+ lies in the presence of an additional phosphate group on the 2' carbon of the ribose moiety attached to adenine in NADP+ [3]. This seemingly minor modification creates a significant functional divergence, enabling enzymes to distinguish between the two cofactors and compartmentalize their metabolic roles.

The redox-active component of both molecules is the nicotinamide ring, which undergoes reversible reduction through a two-electron hydride transfer mechanism [3]. When reduced, NAD+ and NADP+ accept a hydride ion (H-, which is equivalent to a proton and two electrons), converting to NADH and NADPH, respectively. This reduction occurs specifically at the 4-position of the pyridine ring in the nicotinamide moiety, converting the quaternary nitrogen to a tertiary nitrogen, which eliminates its positive charge [3].

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of NAD(H) and NADP(H)

| Characteristic | NAD(H) | NADP(H) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Two nucleotides (adenine and nicotinamide) | Identical to NAD(H) with additional phosphate |

| Phosphate Groups | One phosphate group connecting nucleotides | Additional phosphate at 2' position of adenine ribose |

| Redox Active Site | Nicotinamide ring | Identical nicotinamide ring |

| Primary Cellular Role | Catabolic processes | Anabolic processes and antioxidant defense |

| Typical Reduction State | Maintained predominantly oxidized (low NADH/NAD+ ratio) | Maintained predominantly reduced (high NADPH/NADP+ ratio) |

| Redox Reaction | NAD+ + 2e- + H+ NADH | NADP+ + 2e- + H+ NADPH |

The Hydride Transfer Mechanism

All NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH reactions in biological systems involve two-electron redox steps in which a hydride ion is transferred from an organic molecule to the positively charged nitrogen of the nicotinamide ring, which serves as an electron sink [3]. This hydride transfer mechanism is fundamental to the redox function of these cofactors in dehydrogenase-catalyzed reactions. The reaction is reversible, allowing both oxidized and reduced forms to participate in metabolic pathways according to cellular requirements.

The structural similarity between NADH and NADPH means they share identical spectral properties, with both exhibiting intrinsic fluorescence in their reduced forms while their oxidized forms are non-fluorescent [5] [2]. This photophysical property has been exploited for monitoring cellular redox states since the 1950s [2], though it presents challenges in distinguishing between the two pools in living systems without advanced techniques such as fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) [5] [6].

Quantitative Redox Properties and Metabolic Roles

Cellular Homeostasis and Compartmentalization

The NAD(H) and NADP(H) pools are maintained in distinct redox states to support their specialized metabolic functions. The NADH/NAD+ ratio is typically kept low (approximately 0.01-0.05) in the cytosol to facilitate catabolic processes, as NAD+ is required as an electron acceptor in glycolysis and other oxidative pathways [2] [4]. Conversely, the NADPH/NADP+ ratio is maintained high to support reductive biosynthesis and antioxidant defense mechanisms [2] [4]. This differential regulation is achieved through compartmentalization, with distinct enzymatic machineries regulating these pools in different subcellular locations [1] [7].

The conversion between NAD(H) and NADP(H) is tightly controlled by specific enzymes. NAD kinases (NADKs) facilitate the synthesis of NADP+ from NAD+ by adding the additional phosphate group, while NADP(H) phosphatases (specifically MESH1 and nocturnin in mammals) convert NADP(H) back to NAD(H) [4]. This interconversion represents a crucial regulatory node in maintaining cellular redox homeostasis [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Properties and Metabolic Roles of NAD(P)H

| Parameter | NADH | NADPH |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Lifetime (free) | ~400 ps [5] | ~400 ps [5] |

| Fluorescence Lifetime (enzyme-bound) | 1340-5300 ps (depending on conformation) [5] | 1590-5300 ps (depending on conformation) [5] |

| Typical Cellular Ratio (Reduced/Oxidized) | Low (0.01-0.05 in cytosol) [2] | High (maintained in reduced state) [2] |

| Primary Metabolic Functions | Glycolysis, TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation [1] [2] | Fatty acid synthesis, cholesterol synthesis, antioxidant defense [1] [2] |

| Binding Affinity to NAPstar Biosensors (Kr) | 24.4-248.9 µM [7] | 0.9-11.6 µM (NADPH/NADP+ ratio) [7] |

Fluorescence Properties and Lifetime Characteristics

The intrinsic fluorescence of NADH and NADPH provides a valuable window into cellular metabolism. When probed using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), NAD(P)H emission typically resolves into two lifetime components: a short component (τ1 = 300-500 ps) associated with freely diffusing species, and a longer component (τ2 = 1500-4500 ps) attributed to enzyme-bound forms [5]. The relative abundance of these species is quantified as α2, representing the fraction of the emitting population exhibiting the longer lifetime [5].

Recent research has revealed that different enzyme binding configurations influence the fluorescence decay of NAD(P)H in live cells [5]. Specifically, the fluorescence lifetimes of bound NADH and NADPH are sensitive to enzyme conformations, with the ~400 ps lifetime of free NADH increasing to 1340(±40)ps in open enzyme conformations and 3200(±200)ps in substrate-free closed conformations [5]. The increases for NADPH were similarly significant, from ~400 ps to 1590(±50)ps and 4400(±200)ps, respectively [5]. These lifetime changes reflect the environmental sensitivity of the nicotinamide moiety, which becomes constrained in enzyme active sites during catalytic cycles.

Advanced Measurement Techniques and Methodologies

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM)

FLIM has emerged as a powerful technique for probing NAD(P)H redox states in living systems with subcellular resolution. The methodology exploits the environmental sensitivity of NAD(P)H fluorescence lifetimes to distinguish between free and protein-bound populations, providing insights into metabolic activity [5] [2] [6]. Modern implementation typically involves time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) on multiphoton microscopy systems to achieve optimal spatial and temporal resolution [5].

Detailed FLIM Protocol for NAD(P)H:

- Sample Preparation: Cells or tissues are cultured in appropriate medium (e.g., DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum for HEK293 cells) and plated on glass-bottom dishes for imaging [5].

- Image Acquisition: A femtosecond pulsed laser (e.g., 80 MHz Ti:Sapphire laser at 720 nm excitation) is used for two-photon excitation. Emission is collected through a 440±40 nm bandpass filter to isolate NAD(P)H fluorescence [5].

- Photon Counting: Fluorescence photons are detected using hybrid photomultiplier tubes and processed with TCSPC electronics, histogramming counts at 14.6-ps time intervals [5].

- Lifetime Analysis: Fluorescence decay curves are fitted to a bi-exponential model: I(t) = α1exp(-t/τ1) + α2exp(-t/τ2), where τ1 and τ2 represent the short and long lifetime components, respectively, and α1 and α2 their relative amplitudes [5] [6].

- Data Interpretation: Changes in the mean lifetime (τmean = α1τ1 + α2τ2) and bound fraction (α2) are interpreted in the context of metabolic perturbations, with increased α2 generally indicating a more oxidized NAD(H) pool [6].

Genetically Encoded Biosensors

The development of genetically encoded biosensors represents a significant advancement in monitoring subcellular NADP redox dynamics. The recently introduced NAPstar family of biosensors enables real-time, specific measurements of NADPH/NADP+ ratios across a broad dynamic range with subcellular resolution [7]. These sensors are based on the bacterial transcriptional repressor Rex, which undergoes conformational changes upon NADPH/NADP+ binding that alter the fluorescence of a fused fluorescent protein [7].

NAPstar Implementation Protocol:

- Sensor Expression: Cells are transfected with NAPstar constructs using appropriate gene delivery methods (e.g., lentiviral transduction for stable expression).

- Ratiometric Imaging: Fluorescence is excited at approximately 400 nm, and emission is collected at 515 nm for the T-Sapphire component and at the appropriate wavelength for the mCherry reference fluorophore (excitation ~587 nm, emission ~610 nm) [7].

- Calibration: The TS/mCherry fluorescence ratio is calibrated against known NADPH/NADP+ ratios to establish a standard curve.

- In Vivo Measurement: Live-cell imaging is performed under experimental conditions, with the TS/mCherry ratio providing quantitative information about compartment-specific NADP redox states [7].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NAD(P)H Redox Studies

| Reagent / Technology | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| NADMED Assay Kits | Precise measurement of all NAD(P)H forms [8] | Quantifies NAD+, NADH, NADP+, NADPH, GSSG, GSH; compatible with standard lab workflows |

| NAPstar Biosensors | Genetically encoded NADPH/NADP+ ratio sensing [7] | Real-time monitoring; subcellular resolution; Kr(NADPH/NADP+) range: 0.9-11.6 µM |

| FLIM with trFAIM | Time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy imaging [5] | Identifies enzyme binding configurations; distinguishes NADH vs NADPH contributions |

| FK866 (NAD+ Biosynthesis Inhibitor) | Experimental NAD(H) pool depletion [6] | NAMPT inhibitor; reduces NAD(H) pool size; increases NADH fluorescence lifetime |

| Nicotinamide Riboside (NR) | NAD+ precursor to increase NAD(H) pool [6] | Boosts NAD(H) levels via salvage pathway; decreases NADH fluorescence lifetime |

Experimental Applications and Methodological Considerations

Distinguishing Pool Size from Redox State

A critical advancement in NAD(P)H fluorescence research has been the development of methodologies to differentiate between changes in NAD(H) pool size versus alterations in redox state. Traditional intensity-based measurements cannot distinguish these parameters, as both increased reduction and increased total pool size elevate NAD(P)H fluorescence intensity [6]. FLIM addresses this limitation through careful analysis of lifetime components.

Experimental Approach for Pool Size Assessment:

- Chemical Modulation: Treat cells with NAD+ precursors (e.g., nicotinamide riboside, 300 µM) to increase pool size, or inhibitors (e.g., FK866, 5 nM) to decrease pool size [6].

- FLIM Measurement: Acquire NADH lifetime data across cellular compartments (mitochondria, cytoplasm, nucleus).

- Biochemical Validation: Quantify NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH levels biochemically from parallel samples to correlate lifetime changes with actual pool sizes [6].

- Metabolic Cross-Validation: Assess respiratory parameters (e.g., Oroboros respirometry) and glycolytic flux (lactate secretion) to confirm that lifetime changes reflect pool size alterations rather than redox state modifications [6].

This approach has revealed that increased NAD(H) pool size decreases the mean NADH lifetime, particularly in mitochondria, while decreased pool size increases lifetime across cellular compartments [6]. These patterns can be distinguished from redox-induced changes through their differential effects on lifetime components and correlation with biochemical measurements.

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While NAD(P)H fluorescence techniques provide powerful insights into cellular metabolism, several important considerations must be addressed for proper experimental design and data interpretation:

- pH Sensitivity: The fluorescence properties of NAD(P)H, particularly lifetime measurements, can be influenced by local pH variations, especially in the mitochondrial matrix where pH fluctuations occur during metabolic transitions [6].

- Protein Binding Specificity: The fluorescence lifetime of enzyme-bound NAD(P)H varies significantly depending on the specific enzyme and its conformational state, with different binding configurations associated with lifetimes both longer and shorter than unbound NAD(P)H [5].

- Spectral Overlap: The identical spectral properties of NADH and NADPH necessitate advanced techniques such as FLIM or genetically encoded biosensors to distinguish their contributions to the total fluorescence signal [2] [7].

- Compartmentalization: The NAD(H) and NADP(H) pools are highly compartmentalized within cells, with distinct subcellular redox states that may not be reflected in whole-cell measurements [1] [7].

Advanced techniques such as time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy imaging (trFAIM) can address some of these limitations by identifying multiple enzyme binding configurations and their influence on fluorescence decay kinetics [5]. Combined with mathematical modeling of redox-dependent binding equilibria, these approaches provide increasingly sophisticated interpretation of NAD(P)H fluorescence in the context of cellular biochemistry.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a fundamental coenzyme essential for cellular metabolism, serving as a critical cofactor for oxidoreductases and a substrate for NAD+-consuming enzymes such as sirtuins, PARPs, and CD38. The biosynthesis and balance of NAD+ and its phosphorylated counterpart, NADP+, are pivotal for maintaining redox homeostasis, energy metabolism, and numerous biological processes. This whitepaper delineates the three primary NAD+ biosynthetic pathways—de novo, Preiss-Handler, and salvage—framed within the context of redox biology research. We provide a comprehensive technical guide detailing pathway mechanisms, key enzymes, and regulatory checkpoints, supplemented with structured quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualization tools. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review underscores the interconnectedness of NAD+ metabolism with cellular redox states and highlights emerging therapeutic strategies targeting these pathways for treating metabolic diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer.

The nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) / reduced NAD+ (NADH) and NADP+ / reduced NADP+ (NADPH) redox couples are indispensable for maintaining cellular redox homeostasis and modulating a plethora of biological events, including cellular metabolism [1]. NAD+ functions not only as a coenzyme for oxidoreductases but also as a substrate for NAD+-consuming enzymes, such as sirtuins (SIRT1-7), poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), and cADP-ribose synthases (CD38/CD157) [1]. The phosphorylated form, NADP+, together with its reduced form, NADPH, is primarily involved in maintaining redox balance and supporting biosynthetic pathways for fatty acids and nucleic acids [1]. Deficiency or imbalance of these redox couples has been associated with numerous pathological disorders, including cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and aging [1]. The biosynthesis and distribution of cellular NAD(H) and NADP(H) are highly compartmentalized, making it critical to understand how cells maintain the steady levels of these redox couples to ensure normal functions and avoid redox stress [1]. This review focuses on the three major NAD+ biosynthetic pathways, examining their distinct roles, regulation, and contributions to the cellular redox state.

NAD+ Biosynthetic Pathways

In mammalian cells, NAD+ is synthesized from various precursors, including tryptophan (Trp), nicotinic acid (NA), nicotinamide (NAM), and nicotinamide riboside (NR), through three established pathways: the de novo pathway, the Preiss-Handler pathway, and the salvage pathway [1]. The salvage pathway predominates in most cell types, but all pathways are crucial for maintaining NAD+ pools in different tissues and under varying physiological conditions [1].

The De Novo Pathway from Tryptophan

De novo NAD+ synthesis from the amino acid L-tryptophan is an eight-step process mediated by enzymes in the kynurenine pathway [9] [1]. The first and rate-limiting step is the conversion of L-tryptophan to N-formylkynurenine, catalyzed by either indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO) [1]. TDO is primarily expressed in the liver, while IDO expression has been detected in extrahepatic cells, including human vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, dermal fibroblasts, macrophages, neurons, microglia, and astrocytes [1]. Subsequent steps involve the transformation of N-formylkynurenine to kynurenine, then to 3-hydroxykynurenine, and finally to an unstable intermediate, 2-amino-3-carboxy-muconate-semialdehyde (ACMS) [9] [1]. ACMS represents a critical branch point: it can be decarboxylated by ACMS decarboxylase (ACMSD) and removed from the NAD+ synthesis pathway, or it can spontaneously cyclize to form quinolinic acid (QA) [1]. QA is then converted to nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NAMN) by quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase (QPRT). This QPRT reaction is inefficient and constitutes a second rate-limiting step, rendering tryptophan-dependent synthesis less efficient than the other NAD+ biosynthetic pathways [1]. From NAMN, the pathway converges with the Preiss-Handler route.

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the De Novo Synthesis Pathway

| Enzyme | Gene | Function | Tissue/Organelle Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase | TDO2 | Converts Trp to N-formylkynurenine (rate-limiting) | Primarily liver [1] |

| Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase | IDO1 | Converts Trp to N-formylkynurenine (rate-limiting) | Extrahepatic; endothelial cells, fibroblasts, immune cells [1] |

| Kynurenine 3-hydroxylase | N/A | Hydroxylates kynurenine to 3-hydroxykynurenine | Abundant in liver, placenta [1] |

| ACMS decarboxylase | ACMSD | Decarboxylates ACMS, diverting it from NAD+ synthesis | Regulates NAD+ yield from Trp [1] |

| Quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase | QPRT | Converts quinolinic acid to NAMN (rate-limiting) | Low efficiency [1] |

Diagram 1: The de novo biosynthesis pathway of NAD+ from tryptophan. Key regulatory enzymes and branch points are highlighted.

The Preiss-Handler Pathway

The Preiss-Handler pathway utilizes dietary nicotinic acid (NA, or niacin) as a precursor [9]. This pathway was first identified in human erythrocytes and rat liver and involves a three-step process to convert NA into NAD+ [1]. The first step is the conversion of NA to NAMN, catalyzed by NA phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT) at the expense of phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) [9] [1]. NAPRT expression is widespread, and its mRNA has been detected in almost all human tissues tested [1]. Interestingly, NAPRT activity is subject to complex allosteric regulation by ATP and various metabolites. ATP can stimulate or inhibit NAPRT activity at low or high concentrations, respectively, while metabolites like dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and pyruvate stimulate its activity, and others like glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) and acetyl-CoA inhibit it [1]. NAMN, the product of this reaction, serves as the converging point with the de novo pathway. It is then adenylated to NAAD by nicotinic acid mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNATs) [9]. The final step is the amidation of NAAD to NAD+ by NAD+ synthetase (NADSYN), which uses glutamine or ammonia as an amide donor [9] [1]. NA is a more efficient NAD+ precursor than tryptophan, as 1 mg of dietary NA is equivalent to approximately 60 mg of dietary Trp [1].

The Salvage Pathway

The NAD+ salvage pathway recycles nicotinamide (NAM) generated as a by-product of the enzymatic activities of NAD+-consuming enzymes, such as sirtuins, PARPs, and CD38 [9]. This pathway is crucial for maintaining NAD+ levels in most cell types and predominates under normal physiological conditions [1]. The rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway is nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which recycles NAM into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) [9] [1]. Subsequently, NMN is converted into NAD+ via the action of NMN adenylyltransferases (NMNATs) [9]. In mammals, three isoforms of NMNATs exist with distinct tissue and organelle-specific distributions, which explains the cellular compartmentalization of NAD+ synthesis [1]. NMNAT1 is an exclusively nuclear enzyme ubiquitously expressed, with high abundance in the heart and skeletal muscle. NMNAT2 is located in the cytosol and Golgi apparatus and is principally expressed in the brain. NMNAT3 is found in the cytosol and mitochondria and is mostly present in the human lung and spleen [1]. The salvage pathway is a key regulatory point in NAD+ metabolism, and its inhibition can significantly impact cellular NAD+ levels.

Table 2: Core Enzymes of the Preiss-Handler and Salvage Pathways

| Pathway | Enzyme | Gene | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preiss-Handler | Nicotinic Acid Phosphoribosyltransferase | NAPRT1 | Converts NA to NAMN | Widespread expression; allosterically regulated by ATP & metabolites [1] |

| NMN Adenylyltransferases | NMNAT1/2/3 | Converts NAMN to NAAD | Three isoforms with distinct subcellular localizations [9] [1] | |

| NAD+ Synthetase | NADSYN1 | Converts NAAD to NAD+ | Uses glutamine/ammonia [9] | |

| Salvage | Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase | NAMPT | Recycles NAM to NMN (rate-limiting) | Key regulator of NAD+ levels via salvage [9] [1] |

| NMN Adenylyltransferases | NMNAT1/2/3 | Converts NMN to NAD+ | Same enzymes as Preiss-Handler, different substrate [9] | |

| NAD+-Consuming Enzymes | SIRTs, PARPs, CD38 | Generate NAM as a by-product | Create demand for the salvage pathway [9] |

Diagram 2: The Preiss-Handler and Salvage pathways. The salvage pathway forms a cycle, recycling NAM generated by NAD+-consuming enzymes.

Quantitative Pathway Comparison

The three biosynthetic pathways contribute differently to the cellular NAD+ pool, exhibit distinct efficiencies, and are active in various tissue types. Understanding these quantitative differences is essential for designing targeted metabolic interventions.

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of NAD+ Biosynthetic Pathways

| Characteristic | De Novo Pathway | Preiss-Handler Pathway | Salvage Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Precursor | Tryptophan [1] | Nicotinic Acid (NA) [9] | Nicotinamide (NAM) [9] |

| Precursor Efficiency | ~60 mg Trp ≈ 1 mg NA [1] | High efficiency [1] | High efficiency; dominant in most cells [1] |

| Key Rate-Limiting Enzyme(s) | IDO/TDO; QPRT [1] | NAPRT [1] | NAMPT [1] |

| Tissue Prevalence | Liver (TDO); widespread extrahepatic (IDO) [1] | Widespread (NAPRT expressed in most tissues) [1] | Predominant in most cell types [1] |

| Major Metabolic Role | De novo generation from amino acid | Generation from vitamin precursor | Recycling of NAM from signaling enzymes |

Interplay with NADPH and Redox Biology

The cellular redox state is centrally regulated by the balance of NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH. These redox couples engage in distinct but interconnected metabolic pathways. The NAD+/NADH ratio is a primary regulator of cellular energy metabolism, governing glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. In contrast, the NADP+/NADPH ratio is crucial for reductive biosynthesis (e.g., of fatty acids and nucleic acids) and antioxidant defense, primarily through the glutathione system [1] [10]. The phosphorylation of NAD+ to NADP+ is catalyzed by NAD+ kinase (NADK), the key determinant of cellular NADPH concentration [10]. Research using fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) has demonstrated that the balance between enzyme-bound NADPH and NADH can be quantitatively measured in live cells, as they exhibit distinct fluorescence decay rates when bound to their respective enzymes [10]. This technology has revealed that perturbations in the NADPH/NADH balance are a hallmark of various diseases, including cancer [10]. Furthermore, the redox state of another key metabolite, coenzyme Q (CoQ), which is intricately linked to NADH oxidation in the mitochondrial electron transport chain, also reflects and influences the cellular metabolic state and can contribute to redox signaling [11]. Therefore, the biosynthesis of NAD+ via the de novo, Preiss-Handler, and salvage pathways directly fuels the pools of both NADH and NADPH, making these pathways upstream masters of the cellular redox environment.

Experimental Protocols and Research Tools

Investigating NAD+ biosynthetic pathways and their roles in redox biology requires a combination of genetic, pharmacological, and advanced imaging techniques.

Genetic and Pharmacological Modulation of Pathways

A common experimental approach involves genetically or pharmacologically manipulating key enzymes in the NAD+ biosynthetic pathways to observe the resulting metabolic and phenotypic consequences.

- NADK Manipulation: To alter NADPH levels, researchers can overexpress or knock down NAD+ kinase (NADK). This manipulation significantly changes the [NADPH] without drastically affecting [NADH], allowing for the study of NADPH-specific roles [10].

- NAMPT Inhibition: The inhibitor FK866 is a potent and specific blocker of NAMPT, the rate-limiting enzyme in the salvage pathway. Treating cells with FK866 rapidly depletes NAD+ levels, making it a valuable tool for studying the dependence of cellular processes on the salvage pathway [12].

- Pathway Bypass Strategy: A sophisticated pharmacological strategy to study axon degeneration involved combining FK866 (to inhibit the NMN-producing salvage pathway) with nicotinic acid riboside (NAR). NAR is converted to NAMN via NRK, forcing NAD+ synthesis through the Preiss-Handler pathway and bypassing NMN accumulation. This combination protected neurons, demonstrating a therapeutic strategy for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy [12].

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) of NAD(P)H

FLIM is a powerful non-destructive technique to study the redox state of live cells and tissues by exploiting the autofluorescence of NADH and NADPH.

- Principle: While NADH and NADPH are spectrally identical, their fluorescence decay rates (lifetimes) differ when bound to different enzymes. FLIM measures these nanosecond-scale decay rates, allowing for the quantitative separation of the signals from enzyme-bound NADH and NADPH [10] [13].

- Protocol Outline:

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells (e.g., HEK293) on glass-bottom dishes.

- FLIM Imaging: Acquire images using a two-photon microscope equipped with a time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) system. Excitation wavelength is typically ~740 nm for two-photon excitation of NAD(P)H, with emission collected at 440–470 nm [10] [13].

- Data Fitting: Fit the fluorescence decay curve at each pixel to a multi-exponential model. The short lifetime component (~0.4 ns) corresponds to free NAD(P)H, while the longer, variable lifetime component (τbound, ~1.9–5.7 ns) represents the enzyme-bound pool [10] [13].

- Interpretation: An increase in the average Ï„bound indicates a higher ratio of enzyme-bound NADPH to NADH, as NADPH exhibits a longer fluorescence lifetime when bound [10]. This was validated using NADK+ cells (high NADPH) and the NADPH-binding competitor epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) [10].

Diagram 3: Experimental workflow for Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) to separate NADH and NADPH signals in live cells.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for NAD+ Pathway and Redox Biology Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Brief Description & Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| FK866 | NAMPT inhibitor [12] | Small molecule inhibitor of the salvage pathway's rate-limiting enzyme; used to deplete cellular NAD+ and study pathway dependence. |

| Nicotinic Acid Riboside (NAR) | NAD+ precursor [12] | A deamidated form of NR; channels NAD+ synthesis through the Preiss-Handler pathway (via NAMN), bypassing NMN. Used in combination with FK866. |

| E. coli NMN Deamidase (NMNd) | Enzyme converting NMN to NAMN [12] | A genetic tool expressed in cells to reduce NMN levels. Used to investigate the specific role of NMN in axonal degeneration. |

| EGCG (Epigallocatechin gallate) | Competitive inhibitor of NADPH-binding [10] | Preferentially competes for NADPH-binding sites on enzymes. Used in FLIM experiments to specifically reduce the bound NADPH signal. |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | e.g., NAD+/NADH or NADP+/NADPH sensors [14] | Fluorescent protein-based sensors (e.g., SoNar, iNAP) that allow real-time, compartment-specific monitoring of pyridine nucleotide ratios in live cells. |

| FLIM (Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging) | Endogenous NAD(P)H fluorescence [10] [13] | An advanced microscopy technique that quantifies fluorescence decay rates to separate the contributions of NADH and NADPH based on their enzyme-bound lifetimes. |

| CS17919 | CS17919, MF:C22H20F4N6O2, MW:476.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sinapinic acid | Sinapinic acid, CAS:7361-90-2, MF:C11H12O5, MW:224.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The de novo, Preiss-Handler, and salvage pathways form an integrated network for NAD+ biosynthesis, each with unique characteristics, regulatory mechanisms, and tissue-specific importance. The salvage pathway, centered on NAMPT, is the dominant route for NAD+ production in many cells and represents a critical regulatory node. The de novo and Preiss-Handler pathways provide essential backup and alternative inputs, with the Preiss-Handler pathway being particularly efficient. The interplay between these pathways ensures the maintenance of NAD+ and NADPH pools, which in turn govern cellular redox balance, energy metabolism, and signaling. Disruptions in this balance are implicated in a spectrum of diseases, making enzymes in these pathways attractive therapeutic targets. Contemporary research tools, including specific inhibitors like FK866, precursor molecules like NAR, and advanced imaging techniques like FLIM, are revolutionizing our ability to probe these pathways with high specificity in live cells and tissues. A deep understanding of NAD+ biosynthetic pathways is therefore fundamental to advancing redox biology research and developing novel therapeutics for metabolic, neurodegenerative, and oncological diseases.

In redox biology, the distinct roles of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and its phosphorylated counterpart, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), are fundamentally defined by their subcellular localization. Although these molecules share closely related structures, they are recognized by unique compartmentalized enzymes and exert dramatically different functions within the cell [1] [15]. The NAD pool, comprising NAD+ and NADH, is primarily engaged in catabolic reactions and cellular energy metabolism, functioning as a central regulator of glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [1] [2]. In contrast, the NADP pool (NADP+/NADPH) is predominantly involved in cellular antioxidative effects and anabolic reductive biosynthesis [1] [15]. This functional specialization necessitates strict compartmentalization, with separate cytosolic, mitochondrial, and nuclear pools providing reducing power in each respective location to maintain redox homeostasis and support compartment-specific metabolic needs [16].

The redox states of these separate pyridine nucleotide pools play critical roles in defining the activity of energy-producing pathways, driving oxidative stress, and maintaining antioxidant defences [2]. Defects in the balance of these pathways are associated with numerous diseases, from diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases to heart disease and cancer, making the understanding of their compartmentalization essential for therapeutic development [2] [15]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of the distinct pools of NAD(H) and NADP(H) within cellular compartments, their metabolic roles, and the advanced methodologies used to investigate them.

Compartmentalized NAD(H) and NADP(H) Pools: Distribution and Functions

Quantitative Distribution of Pyridine Nucleotides Across Compartments

The biosynthesis and distribution of cellular NAD(H) and NADP(H) are highly compartmentalized, with distinct pools maintained in the cytosol, mitochondria, and nucleus [1]. The following table summarizes the quantitative distribution and characteristics of these pools based on current research findings.

Table 1: Characteristics of NAD(P)H Pools in Cellular Compartments

| Cellular Compartment | Primary Redox Couple | Typical Ratio | Concentration | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytosol | NAD+/NADH | NADH/NAD+: 0.01-0.05 [2] | NADPH: 3.1 ± 0.3 µM (HeLa cells) [15] | Glycolysis, PPP, fatty acid synthesis, antioxidant defense (GSH system) |

| Mitochondria | NAD+/NADH | Low NADH/NAD+ [2] | NADPH: 37 ± 2 µM (HeLa cells) [15] | TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation, antioxidant defense (mitochondrial TRX, GSH) |

| Nucleus | NAD+/NADH | Varies by cell state | Information not available in search results | Substrate for Sirtuins, PARPs, DNA repair, epigenetic regulation |

Molecular Machinery Maintaining Compartmentalized Pools

The maintenance of separate NAD(H) and NADP(H) pools requires specialized enzymatic machinery and transport systems in each compartment:

NAD Biosynthesis Enzymes: The three isoforms of NMN adenylyltransferases (NMNATs) exhibit distinct organelle-specific distribution. NMNAT1 is an exclusively nuclear enzyme ubiquitously expressed in human tissues, with high abundance in the heart and skeletal muscle. NMNAT2 is located in the cytosol and Golgi apparatus, principally expressed in the brain. NMNAT3 is found in the cytosol and mitochondria, mostly present in human lung and spleen [1]. This tissue- and organelle-specific expression pattern explains the cellular compartmentalization of NAD+ [1].

NADP Biosynthesis: NADP+ is synthesized from NAD+ via NAD kinases (NADKs), which are found in almost all human organs except skeletal muscle and are localized in both cytosol (cNADK) and mitochondria (mNADK) [15]. The mitochondrial NADK (mNADK) has a distinctive feature—it can directly phosphorylate NADH to generate NADPH to alleviate oxidative stress in mitochondria [15].

Redox Shuttles: The malate-aspartate shuttle facilitates the transfer of reducing equivalents from cytosolic NADH to mitochondrial NAD+, linking glycolytic NADH production to mitochondrial respiration [2]. This shuttle plays a significant role in numerous biological processes, including insulin secretion, cancer cell survival, and heart and neurodegenerative diseases [2].

Methodologies for Investigating Compartmentalized Pools

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM)

The intrinsic fluorescence of the reduced forms (NADH and NADPH) has been used as a label-free method for monitoring intracellular redox state for more than 60 years [2]. However, since the fluorescence spectra of NADH and NADPH are indistinguishable, interpreting the signals resulting from their combined fluorescence (labeled NAD(P)H) is complex. Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) offers the potential to discriminate between the two separate pools, as the fluorescence lifetime of these molecules is highly sensitive to changes in their local environment [2].

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Studying Compartmentalized NAD(P)H Pools

| Methodology | Key Principle | Compartment Resolution | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD(P)H FLIM | Measures fluorescence lifetime (optical half-life) sensitive to molecular environment [2] | Subcellular (mitochondrial vs. cytosolic) | Discrimination between free and protein-bound NAD(P)H; metabolic state assessment |

| Stable Isotope Tracing (²H) | Tracing hydrogen in compartmentalized reactions using NADPH as cofactor [16] | Can resolve cytosolic vs. mitochondrial pathways | Quantifying PPP contribution to cytosolic NADPH; resolving direction of compartmentalized redox reactions |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | Protein-based sensors with selective compartment targeting [1] | Specific compartment targeting (e.g., mito-GFP) | Real-time monitoring of compartment-specific NADPH/NADP+ ratios or NADH levels |

| Biochemical Fractionation | Physical separation of cellular compartments followed by HPLC/MS analysis | Isolated mitochondria, cytosol, nuclei | Absolute quantification of pool sizes and redox ratios in purified organelles |

Stable Isotope Tracing for NADPH Metabolism

A sophisticated approach to resolve NADP(H)-dependent pathways in distinct compartments involves using ²H stable isotopes to trace NADPH metabolism. This method enables researchers to:

- Quantify the pentose phosphate pathway contribution to cytosolic NADPH [16]

- Distinguish between cytosolic and mitochondrial NADPH using specialized reporter systems [16]

- Resolve the direction of otherwise identical compartmentalized redox reactions in intact cells [16]

By tracing hydrogen in compartmentalized reactions that use NADPH as a cofactor, including the production of 2-hydroxyglutarate by mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase enzymes, researchers can observe metabolic pathway activity in these distinct cellular compartments [16]. Using this system, scientists have determined the direction of serine/glycine interconversion within the mitochondria and cytosol, highlighting the ability of this approach to resolve compartmentalized reactions in intact cells [16].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: NAD(P)H FLIM for Mitochondrial Redox State Assessment

Principle: This protocol utilizes the natural fluorescence of NADH and NADPH to assess compartmentalized redox states through fluorescence lifetime measurements, which can help distinguish between protein-bound and free states of these cofactors [2].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Culture cells on glass-bottom dishes or prepare tissue slices (100-300 µm thickness) to maintain physiological conditions.

- Two-Photon Excitation: Use a mode-locked titanium-sapphire laser tuned to 740 nm for two-photon excitation of NAD(P)H fluorescence.

- Emission Collection: Collect emitted fluorescence through a 460/80 nm bandpass filter to isolate the NAD(P)H signal.

- Lifetime Data Acquisition: Acquire time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) data using a high-sensitivity detector (e.g., photomultiplier tube or hybrid detector).

- Lifetime Analysis: Fit fluorescence decay curves to a bi-exponential model using specialized software:

- Short lifetime component (τ₠≈ 0.4 ns): Represents free NAD(P)H

- Long lifetime component (τ₂ ≈ 2.0 ns): Represents protein-bound NAD(P)H

- Compartment-Specific Analysis: Use mitochondrial markers (e.g., TMRM) to isolate mitochondrial signals, or analyze distinct subcellular regions.

Data Interpretation: Shifts toward longer average lifetimes indicate increased protein binding of NAD(P)H, typically associated with a more oxidized state of the NAD pool in energy-producing pathways [2].

Protocol: Compartment-Specific NADPH Production Using ²H Tracing

Principle: This method uses deuterated water (²H₂O) to trace NADPH metabolism in specific cellular compartments by following the incorporation of deuterium into metabolites dependent on NADPH as a cofactor [16].

Procedure:

- Isotope Labeling: Incubate cells in culture medium supplemented with 4% ²H₂O for 24-48 hours to achieve equilibrium labeling.

- Metabolite Extraction: Harvest cells and use methanol:water extraction to preserve redox metabolites.

- Compartmental Fractionation (Optional): Use digitonin-based permeabilization or mechanical fractionation to isolate mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions.

- LC-MS Analysis: Analyze metabolites using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) with multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for NADPH-dependent metabolites.

- Deuterium Incorporation Quantification: Calculate the percentage of deuterium enrichment in metabolites such as 2-hydroxyglutarate (produced by mutant IDH enzymes) that serve as reporters for NADPH utilization.

- Pathway Contribution Analysis: Use mathematical modeling to attribute NADPH production to specific pathways (PPP, ME, IDH) in each compartment.

Applications: This approach can determine the relative contributions of different pathways to cytosolic versus mitochondrial NADPH pools and resolve the direction of redox reactions within specific compartments [16].

Visualization of Compartmentalized NAD(P)H Metabolism

Diagram Title: NAD(P)H Metabolism Across Cellular Compartments

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying NAD(P)H Compartmentalization

| Tool/Reagent | Vendor/Provider | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD/NADP Assay Kits | NADMED [8] [17] | Precise measurement of all four forms (NAD+, NADH, NADP+, NADPH) | Eliminates limitations of previous methods; fast, reliable, cost-effective; integrates with standard workflows |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | Multiple academic sources | Real-time monitoring of compartment-specific NADPH/NADP+ ratios or NADH levels | Targetable to specific compartments (e.g., mito-roGFP); enables live-cell imaging |

| Deuterated Tracers (²H₂O) | Cambridge Isotopes | Tracing NADPH metabolism in specific compartments | Enables quantification of pathway contributions to NADPH pools |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy Systems | Multiple manufacturers (e.g., Leica, Zeiss) | NAD(P)H FLIM for metabolic state assessment | Discriminates between NADH and NADPH based on lifetime; subcellular resolution |

| Compartment-Specific Enzyme Inhibitors | Multiple suppliers (e.g., Sigma, Tocris) | Selective inhibition of compartment-specific NADPH-producing enzymes | cNADK vs mNADK inhibitors; G6PD inhibitors; IDH-specific inhibitors |

| Sugemalimab | Sugemalimab, CAS:2256084-03-2, MF:C6H11ClN2, MW:146.62 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nlrp3-IN-13 | Nlrp3-IN-13, MF:C19H15N3O3S, MW:365.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The compartmentalization of NAD(H) and NADP(H) pools represents a fundamental organizational principle of eukaryotic cells that enables the simultaneous regulation of diverse metabolic processes. Understanding these separate pools—with their distinct biosynthesis pathways, redox states, and functional roles—is crucial for advancing redox biology research and developing targeted therapeutic interventions. The continued refinement of research tools, particularly those enabling precise measurement and spatial resolution of these metabolites, will drive future discoveries in metabolic diseases, cancer, aging, and degenerative disorders. As these methodologies become more sophisticated and accessible, researchers will be better equipped to address a host of pathological conditions characterized by disrupted NAD(P)H homeostasis.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) serves as a central redox coenzyme in catabolic energy metabolism, channeling electrons from metabolic pathways to the mitochondrial electron transport chain. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of NADH's role in glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, emphasizing its critical function in energy transduction. We present quantitative data on ATP yields, detailed methodologies for investigating NADH metabolism, and visualization of key pathways. The integration of NADH production and oxidation represents a fundamental coupling mechanism that enables efficient energy harvesting from fuel molecules, with significant implications for therapeutic targeting in metabolic diseases and cancer.

NADH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced form) functions as an essential electron carrier in cellular redox reactions, operating in concert with its oxidized form NAD+ [18]. This redox couple facilitates the transfer of electrons in numerous metabolic processes, particularly those involved in energy extraction from organic fuels. The NAD+/NADH ratio reflects the cellular redox state and regulates metabolic flux between anabolic and catabolic pathways [18]. In the context of energy metabolism, NADH serves as a critical link between carbon-oxidizing pathways and the proton-motive force generation system, ultimately driving ATP synthesis.

The molecular structure of NADH enables its electron-carrying capacity through the nicotinamide ring, which undergoes reversible oxidation and reduction reactions. When NAD+ accepts two electrons and one proton (a hydride ion), it converts to NADH, storing potential energy that can be harnessed for ATP production [19]. This redox coupling is particularly crucial in the two primary ATP-generating processes in aerobic cells: glycolysis in the cytosol and oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria.

NADH in Glycolysis

Glycolytic Pathway and NADH Production

Glycolysis is a ten-step metabolic pathway occurring in the cytosol that converts one glucose molecule into two pyruvate molecules [20] [21]. This process can be divided into two distinct phases: the preparatory (investment) phase requiring ATP consumption, and the pay-off phase generating ATP and reducing equivalents [20]. A critical NADH-producing step occurs at the sixth reaction of glycolysis, where glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate undergoes oxidation to 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, catalyzed by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [20]. During this reaction, NAD+ is reduced to NADH, simultaneously with the incorporation of inorganic phosphate to create a high-energy acyl phosphate group.

The glycolytic pathway yields a net production of 2 ATP molecules and 2 NADH molecules per glucose molecule [20] [21]. Under aerobic conditions, these NADH molecules must be reoxidized to regenerate NAD+, which is essential for sustaining glycolytic flux. In eukaryotic cells, this is accomplished by shuttling the reducing equivalents into mitochondria for oxidation by the electron transport chain.

Regulation at the Molecular Level

Glycolytic regulation occurs at several key enzymatic steps, including those catalyzed by hexokinase, phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), and pyruvate kinase [20]. PFK-1 represents the primary regulatory point, controlled by allosteric effectors including ATP, citrate, and fructose-2,6-bisphosphate. The latter is generated by phosphofructokinase-2 (PFK-2), whose activity is hormonally regulated through insulin-mediated dephosphorylation [20]. This intricate regulatory network ensures that glycolytic flux responds to cellular energy status and substrate availability.

Table 1: NADH and ATP Balance in Glycolysis

| Reactant/Product | Quantity per Glucose Molecule | Cellular Location |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | -1 | Cytosol |

| NAD+ | -2 | Cytosol |

| ADP | -2 | Cytosol |

| Pyruvate | +2 | Cytosol |

| NADH | +2 | Cytosol |

| ATP | +2 (net) | Cytosol |

NADH in Oxidative Phosphorylation

Electron Transport Chain Architecture

The mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) consists of four protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane, plus two mobile electron carriers [22] [23] [24]. NADH derived from both glycolysis and the citric acid cycle delivers electrons to Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase), initiating the electron transfer process [23]. Complex I catalyzes the transfer of electrons from NADH to ubiquinone (coenzyme Q), coupled with the translocation of four protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane [23] [24].

The electron flow continues through Complex III (ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductase) and Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), with additional proton pumping at each complex [22] [23]. The final electron acceptor is molecular oxygen, which is reduced to water at Complex IV [23]. Throughout this process, the stepwise transfer of electrons through complexes with progressively higher reduction potentials enables the controlled release of energy, which is harnessed to create the proton gradient.

Chemiosmotic Coupling and ATP Synthesis

The proton gradient generated by electron transport creates an electrochemical potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane, comprising both a pH gradient (ΔpH) and an electrical potential (ΔΨ) [22]. This proton-motive force drives ATP synthesis through Complex V (ATP synthase), which couples the energetically favorable flow of protons back into the mitochondrial matrix with the phosphorylation of ADP to ATP [22] [23]. The ATP synthase operates through a rotational catalytic mechanism, where proton passage through the F₀ subunit induces conformational changes in the F₠subunit that facilitate ATP synthesis [22].

The oxidation of one NADH molecule typically drives the synthesis of approximately 2.5-3 ATP molecules, though theoretical yields may be higher [22] [23]. This high ATP yield underscores the metabolic advantage of aerobic respiration over anaerobic pathways.

Table 2: ATP Yield from Glucose Oxidation via NADH-Dependent Processes

| Metabolic Process | ATP Produced | NADH Produced | FADHâ‚‚ Produced | Total ATP (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycolysis | 2 (net) | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pyruvate Oxidation | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Citric Acid Cycle | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | 0 | -10 (consumed) | -2 (consumed) | ~28 |

| Total | 4 | - | - | ~32 |

Experimental Approaches for NADH Metabolism

Glycolysis Inhibition Studies

Research investigating the interplay between glycolysis and cellular redox state often employs specific glycolytic inhibitors to dissect metabolic contributions [25]. Common inhibitors include:

- 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG): A glucose analog that competitively inhibits hexokinase, the first enzyme in glycolysis [25].

- 3-bromopyruvate (3-BP): A potent alkylating agent that inhibits hexokinase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [25].

- Dichloroacetate (DCA): Inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, thereby activating pyruvate dehydrogenase and promoting oxidative metabolism over glycolysis [25].

Experimental protocols typically involve treating cells (e.g., HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells) with these inhibitors alone or in combination with chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin [25]. Treatment duration of 48 hours at physiologically relevant concentrations (e.g., 1μM doxorubicin, 2mM 2-DG, 10μM 3-BP, or 1mM DCA) allows assessment of metabolic and oxidative stress parameters [25].

Assessment of Oxidative Stress Markers

Methodologies for evaluating cellular response to metabolic perturbation include:

- Cytotoxicity analysis: MTT assay measuring mitochondrial reductase activity as an indicator of cell viability [25].

- Apoptosis and necrosis detection: Annexin V staining combined with ethidium homodimer III exclusion assessed via image cytometry [25].

- Oxidative stress markers: Measurement of lipid peroxidation products (malondialdehyde, 4-hydroxyalkenals), reduced glutathione (GSH) levels, and NADPH concentrations [25].

- Gene expression analysis: Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of genes involved in energy metabolism and antioxidant defense [25].

- Metabolite consumption assays: Measurement of glutamine uptake to assess alternative metabolic pathway activation [25].

NADH Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM)

Advanced techniques such as Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) enable non-invasive monitoring of NADH metabolic states in living cells [26]. This approach capitalizes on the inherent fluorescence of NADH and its sensitivity to enzyme binding, which alters fluorescence decay kinetics. Time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy imaging can distinguish between free and protein-bound NADH, providing insights into the redox state and metabolic flux in different cellular compartments [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for NADH Metabolism Studies

| Reagent | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Deoxyglucose (2-DG) | Competitive hexokinase inhibitor | Mimics glucose; traps glycolysis at first step [25] |

| 3-Bromopyruvate (3-BP) | Alkylating agent; inhibits HK and GAPDH | Potent glycolysis inhibitor; induces oxidative stress [25] |

| Dichloroacetate (DCA) | PDK inhibitor; promotes oxidative metabolism | Shifts metabolism from glycolysis to glucose oxidation [25] |

| NAD+ Precursors (NMN, NR) | Boost cellular NAD+ levels | Enhance sirtuin activity; improve mitochondrial function [18] |

| MTT Assay Kit | Cell viability assessment | Measures mitochondrial reductase activity [25] |

| Annexin V Apoptosis Assay | Apoptosis and necrosis detection | Distinguishes early/late apoptosis and necrosis [25] |

| Cytochrome c | Electron transport chain component | Mobile electron carrier between Complex III and IV [23] [24] |

| Coenzyme Q10 | Electron transport chain component | Lipid-soluble electron carrier between Complex I/II and III [23] [24] |

Pathway Visualizations

Therapeutic Implications and Research Perspectives

The central role of NADH in energy metabolism presents attractive targets for therapeutic intervention, particularly in cancer and metabolic disorders. Cancer cells frequently exhibit enhanced glycolytic flux (the Warburg effect) with subsequent lactate production, even under aerobic conditions [25]. This metabolic reprogramming creates dependencies that can be exploited therapeutically. Glycolysis inhibitors such as 2-DG, 3-BP, and DCA can selectively target cancer cells by disrupting their primary ATP and biomass production pathways [25]. Furthermore, these inhibitors can sensitize tumor cells to conventional chemotherapeutic agents like doxorubicin by impairing cellular antioxidant defenses through NADPH depletion [25].

Emerging research focuses on NAD+ precursor supplementation (e.g., nicotinamide mononucleotide [NMN] and nicotinamide riboside [NR]) to boost cellular NAD+ levels, potentially ameliorating age-related metabolic decline and mitochondrial dysfunction [18]. These approaches aim to enhance NAD+-dependent processes including sirtuin-mediated deacetylation and DNA repair by PARP enzymes, with implications for healthy aging and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases [18].

Future research directions include elucidating the complex regulation of NAD+ biosynthesis through de novo, Preiss-Handler, and salvage pathways [18], and developing more specific inhibitors targeting NADH-generating or consuming processes. Advanced imaging techniques like FLIM will continue to provide insights into compartmentalized NADH metabolism in living cells [26], enabling more precise manipulation of these fundamental metabolic pathways for therapeutic benefit.

NADPH in Anabolic Processes and Antioxidant Defense Systems

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) serves as an essential electron donor critical for cellular redox homeostasis, reductive biosynthesis, and antioxidant defense. This whitepaper examines the dual role of NADPH in fueling anabolic processes for cell proliferation and maintaining oxidative stress balance through reduced glutathione and thioredoxin systems. We explore the compartmentalized regulation of NADPH metabolism across cytosolic, mitochondrial, and other cellular environments, highlighting recent advances in measurement technologies and therapeutic targeting. Within the broader context of NADPH/NADH redox biology, understanding NADPH homeostasis provides crucial insights for drug development in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and age-related diseases where redox imbalance underpins pathological progression.

NADPH represents a critical redox cofactor that exists in a predominantly reduced state within cells, maintaining a favorable ratio for reductive biochemical reactions [27]. While NADH primarily fuels catabolic processes to generate ATP, NADPH serves as an indispensable electron donor for anabolic reactions and redox defense systems [15]. The structural distinction between these cofactors—an additional phosphate group on the 2' position of the adenosine ribose in NADP(H)—ensures functional separation, as enzymes specifically recognize either NAD(H) or NADP(H) [28] [15].

The regulation of NADPH homeostasis occurs through multiple compartmentalized pathways including the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), folate metabolism, and NAD kinase activity [15]. Recent research has illuminated how distinct NADPH pools in cytosol and mitochondria independently support different cellular functions, with mitochondrial NADPH generated via NADK2 and several NADP+-reducing enzymes [27]. This compartmentalization allows NADPH to simultaneously support biosynthetic pathways while maintaining redox balance in different cellular locations.

The critical balance between NADPH production and consumption creates a vulnerability that can be therapeutically exploited, particularly in cancer cells that maintain high NADPH levels to support rapid growth and combat oxidative stress [15]. This whitepaper comprehensively examines NADPH's multifaceted roles, with specific quantitative data on its metabolic functions, experimental approaches for its study, and emerging therapeutic strategies targeting NADPH metabolism.

Biological Functions of NADPH

Antioxidant Defense Systems

NADPH serves as the primary reducing power for cellular antioxidant systems, maintaining redox homeostasis by regenerating reduced glutathione and thioredoxin [15].

- Glutathione System: NADPH is an essential cofactor for glutathione reductase, which converts oxidized glutathione (GSSG) back to its reduced form (GSH). Reduced glutathione then serves as a cosubstrate for glutathione peroxidase (GPX) to detoxify hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) and other peroxides into water or alcohol [15].

- Thioredoxin System: Thioredoxin reductase (TRXR) utilizes NADPH as an electron donor to maintain reduced thioredoxin (TRX), which contributes to Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ scavenging and provides reducing equivalents for ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) in DNA synthesis [15].

- Enzyme Reactivation: In some cell types, NADPH binds to and reactivates catalase when this Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-disposing enzyme becomes inactivated by its own substrate [15].

The critical role of NADPH in redox defense is particularly evident in cancer cells, which maintain high NADPH levels to prevent excessive oxidative stress while permitting ROS-mediated signaling that supports proliferation [15].

Anabolic Processes

NADPH provides essential reducing power for multiple biosynthetic pathways that support cell growth and proliferation:

Table 1: NADPH-Dependent Anabolic Processes

| Anabolic Process | Key NADPH-Dependent Enzymes | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty Acid Synthesis | Fatty acid synthase (FASN) [28] | Synthesis of fatty acids using acetyl-CoA as primer and malonyl-CoA as two-carbon donor [15] |

| Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Synthesis | Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis (mtFAS) enzymes [27] [29] | Generation of acyl chains for protein lipoylation; enables efficient mitochondrial translation and oxidative metabolism [27] [29] |

| Cholesterol Synthesis | HMG-CoA reductase (HMGCR) [15] | Rate-limiting enzyme of mevalonate pathway for cholesterol and nonsterol isoprenoid synthesis [15] |

| Nucleotide Synthesis | Dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) [15] | Reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate (THF) for de novo biosynthesis of thymidylate and purines [15] |

| Amino Acid Synthesis | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) [27] | Conversion of glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate for proline biosynthesis [27] |

| Drug/Xenobiotic Metabolism | Cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) [15] | Metabolism of drugs, xenobiotics, and steroid hormones [15] |

NADPH in Reactive Oxygen Species Generation

Beyond its antioxidant role, NADPH also serves as a substrate for NADPH oxidases (NOX), which catalyze the generation of superoxide anions or H₂O₂ from NADPH and oxygen [15]. These NOX-mediated ROS function as signaling molecules that regulate various redox-sensitive pathways involved in cancer progression, including those stimulating oncogenes such as Src and Ras [15]. This dual function positions NADPH at the center of redox balance—both preventing oxidative damage through antioxidant systems and facilitating ROS signaling when required for cellular processes.

NADPH Metabolic Pathways and Homeostasis

NADPH homeostasis is regulated by several metabolic pathways that exhibit cell-type and context-dependent contributions. The major NADPH-producing systems maintain compartmentalized NADPH pools to support distinct cellular functions.

Table 2: Major NADPH Producing Pathways and Enzymes

| Pathway/Enzyme | Subcellular Localization | Reaction Catalyzed | Relative Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway (PPP) | Cytosol [15] | G6PD: Glucose-6-phosphate → 6-phosphogluconolactone + NADPH [15] | Primary cytosolic source; major contributor in most cells [15] |

| 6PGD: 6-phosphogluconate → Ribulose-5-phosphate + CO₂ + NADPH [15] | |||

| NAD Kinase (NADK) | Cytosol (NADK1) [15] | NAD⺠+ ATP → NADP⺠+ ADP [15] | De novo NADP⺠synthesis [15] |

| NAD Kinase (NADK2) | Mitochondria [27] [15] | NAD⺠+ ATP → NADP⺠+ ADP [27] [15] | Primary mitochondrial NADP⺠source [27] |

| Malic Enzyme (ME1) | Cytosol [15] | Malate + NADP⺠→ Pyruvate + CO₂ + NADPH [15] | Varies by cell type and metabolic state [15] |

| Malic Enzyme (ME2) | Mitochondria [27] | Malate + NADP⺠→ Pyruvate + CO₂ + NADPH [27] | Mitochondrial NADPH generation [27] |

| Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH1) | Cytosol [15] | Isocitrate + NADP⺠→ α-ketoglutarate + CO₂ + NADPH [15] | Secondary cytosolic source [15] |

| Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH2) | Mitochondria [27] | Isocitrate + NADP⺠→ α-ketoglutarate + CO₂ + NADPH [27] | Mitochondrial NADPH generation [27] |

| Folatemetabolism (MTHFD1) | Cytosol/Mitochondria [30] | Methylenetetrahydrofolate + NADP⺠→ Methenyltetrahydrofolate + NADPH [30] | Secondary source; important in endothelial cells [30] |

The diagram below illustrates the compartmentalization of NADPH metabolism and the key pathways involved in its production and consumption:

Quantitative studies of NADPH concentrations reveal significant compartmental differences. In HeLa cells, NADPH concentration is approximately 3.1 ± 0.3 µM in the cytosol and 37 ± 2 µM in the mitochondrial matrix [15]. The redox potentials of both mitochondrial and cytosolic NADP(H) systems are similar at approximately -400 mV in the liver [15]. These quantitative differences highlight the specialized roles of each compartment, with mitochondria maintaining substantially higher NADPH levels to support its diverse oxidative metabolic functions.

Quantitative NADPH Data in Physiological Contexts

Understanding NADPH concentrations and flux in different physiological and pathological states provides critical insights for therapeutic targeting.

Table 3: Quantitative NADPH Data Across Biological Contexts

| Biological Context | NADPH Level/Parameter | Measurement Method | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| HeLa Cells | Cytosol: 3.1 ± 0.3 µM [15] | Genetically encoded sensors [15] | Baseline compartmental distribution |

| Mitochondria: 37 ± 2 µM [15] | Genetically encoded sensors [15] | Higher mitochondrial capacity | |

| Rat Liver | Total NADP(H): 420 nmol/g wet weight [15] | Enzymatic cycling assays [15] | Tissue-level quantification |

| Mitochondrial: 59% of total [15] | Subcellular fractionation [15] | Major mitochondrial pool | |

| Senescent Endothelial Cells | Cytosolic NADPH significantly elevated [30] | iNap1 sensor [30] | Adaptive response to oxidative stress |

| Mitochondrial NADPH unchanged [30] | iNap3 sensor [30] | Compartment-specific regulation | |

| Cancer Cells | High NADPH maintained [15] | Multiple methods [15] | Supports biosynthesis and redox defense |

| L-threonine Production | NADPH limitation impacts yield (0.65 g/g) [31] | Metabolic engineering [31] | Industrial application dependency |

The regulation of NADPH production pathways shows remarkable plasticity across different cellular states. In senescent endothelial cells, cytosolic NADPH increases through G6PD upregulation, while mitochondrial NADPH remains stable [30]. This compartment-specific regulation highlights how cells can fine-tune NADPH distribution to address distinct metabolic needs in different subcellular locations.

Experimental Approaches for NADPH Research

Genetically Encoded NADPH Sensors

Recent advances in genetically encoded biosensors have revolutionized the study of NADPH dynamics in live cells:

iNap Sensors: The iNap1 sensor enables real-time monitoring of NADPH levels in specific cellular compartments. The experimental workflow involves:

- Transfection of cyto-iNap1 or mito-iNap3 constructs into target cells

- Confocal imaging with excitation at 405/420 nm and 488/485 nm

- Ratio metric analysis (405/488 or 420/485) to determine NADPH concentration

- In situ calibration using digitonin (0.001% for plasma membrane, 0.3% for mitochondrial membrane) permeabilization followed by NADPH titration [30]

Validation: Specificity is confirmed using oxidants like diamide (100 µM) that decrease cyto-iNap1 fluorescence but not mito-iNap3 signals, demonstrating stronger antioxidant capacity in mitochondria [30]. The non-responsive variant iNapc serves as a control for environmental effects [30].

Direct Measurement of Mitochondrial Fatty Acid Synthesis

A novel biochemical method developed by Kim et al. enables direct quantification of mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis (mtFAS) activity:

- Acyl Group Analysis: Modification of a method used in Camelina sativa to directly assess acyl modifications on mammalian NDUFAB1 using mass spectrometry [27] [29]

- Sample Preparation: Isolation of mitochondrial fractions and cleavage of acyl chains from target proteins (DLAT, DLST, or NDUFAB1) [27]

- Mass Spectrometry: Relative quantification of various acyl chains attached to NDUFAB1 provides direct readout of mtFAS pathway activity [27]

- Application: Demonstration that NADK2-derived mitochondrial NADPH is required for acyl chain synthesis by mtFAS [27]

Metabolic Engineering Approaches

The Redox Imbalance Forces Drive (RIFD) strategy represents an innovative approach to manipulate NADPH metabolism:

- NADPH Pool Expansion: "Open source" strategies including:

- Expression of cofactor-converting enzymes

- Heterologous cofactor-dependent enzymes

- Enzymes in NADPH synthesis pathways [31]

- Consumption Reduction: Knocking out non-essential NADPH-consuming genes [31]

- Directed Evolution: Using MAGE to evolve redox-imbalanced engineered strains [31]

- Biosensor Integration: NADPH and product dual-sensing biosensors combined with FACS for high-throughput screening [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for NADPH Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| iNap1/iNap3 | Genetically encoded sensor | Real-time NADPH monitoring in cytosol/mitochondria [30] | Live-cell imaging of NADPH dynamics during senescence [30] |

| SoNar | Genetically encoded sensor | Monitoring NADH/NAD+ ratios [30] | Parallel assessment of NAD and NADPH redox states [30] |

| Digitonin | Chemical reagent | Selective membrane permeabilization [30] | Sensor calibration in specific compartments [30] |

| NADK2 knockout models | Genetic model | Study mitochondrial NADPH functions [27] | Elucidating mtFAS and proline synthesis requirements [27] |

| MTHFD1 inhibitors | Small molecule compounds | Block folate-mediated NADPH production [30] | Investigating endothelial cell senescence [30] |

| G6PD modulators | Chemical compounds | Regulate PPP flux and NADPH production [32] [15] | Studying antioxidant capacity in neuronal systems [32] |

| Folic Acid | FDA-approved drug | Enhances NADPH production via MTHFD1 [30] | Testing therapeutic intervention in vascular aging [30] |

| Sos1-IN-16 | Sos1-IN-16, MF:C30H31F3N4O3, MW:552.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Elironrasib | Elironrasib, CAS:2641998-63-0, MF:C55H78FN9O8, MW:1012.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The experimental workflow for studying compartmentalized NADPH metabolism integrates these tools as shown below:

Therapeutic Implications and Research Directions

Targeting NADPH metabolism represents a promising strategy for various diseases:

- Cancer Therapy: Cancer cells maintain high NADPH levels to support rapid growth and combat oxidative stress, creating a therapeutic vulnerability [15]. Strategies include inhibiting NADPH production pathways (PPP, NADK) or increasing NADPH consumption through pro-oxidant therapies [15].

- Neurodegenerative Disorders: In Parkinson's disease, RAS components regulate G6PD expression and NADPH availability in dopaminergic neurons, suggesting angiotensin receptor modulation as a potential therapeutic approach [32].

- Vascular Aging: Folic acid, identified through high-throughput screening of FDA-approved drugs, increases NADPH via MTHFD1 and ameliorates vascular aging in mouse models [30].

- Metabolic Engineering: The RIFD strategy demonstrates that creating redox imbalance forces can drive production of valuable compounds like L-threonine (117.65 g/L yield) [31].

Future research directions should focus on developing more specific compartment-targeted NADPH modulators, understanding tissue-specific NADPH regulation, and exploring combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple NADPH homeostasis mechanisms.

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Monitoring NAD(H) and NADP(H) Dynamics

Genetically Encoded Biosensors (e.g., iNap, SoNar) for Compartment-Specific Real-Time Imaging

Cellular metabolism relies on the intricate balance of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide cofactors, with NADH serving as a central carrier of reducing equivalents in catabolic processes and NADPH providing reducing power for anabolic reactions and antioxidant defense [1]. The NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH redox couples constitute essential metabolic redox buffers that regulate cellular energy metabolism, redox homeostasis, and signaling pathways [1]. Disruption of these redox systems has been implicated in numerous pathological conditions, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and aging [1]. Historically, methods for measuring these metabolites relied on destructive techniques such as chromatography, mass spectrometry, and enzymatic cycling assays, which provided only static snapshots and failed to preserve spatial and temporal information [33] [34].

The development of genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors has revolutionized our ability to monitor metabolic dynamics in live cells with subcellular resolution [35]. These molecular tools combine ligand-binding domains with fluorescent proteins, enabling real-time tracking of metabolite fluctuations, enzymatic activities, and signaling events in their native cellular context [35]. This technical guide focuses on the emerging class of biosensors designed specifically for monitoring NADPH and NADH redox states, with particular emphasis on compartment-specific imaging applications that are illuminating the spatial organization of redox metabolism in health and disease.

Biosensor Engineering and Design Principles

Molecular Architecture of Redox Biosensors

Genetically encoded biosensors for NADPH and NADH typically employ a modular design consisting of a sensing domain and a reporting domain [35] [7]. The sensing domain is derived from natural bacterial transcriptional regulators or metabolic enzymes that specifically bind NADPH or NADH, while the reporting domain consists of fluorescent proteins whose spectral properties change upon ligand binding.

The Rex protein from Thermus aquaticus (T-Rex) has served as a particularly versatile sensing domain for both NADH and NADPH biosensors [33] [7]. In its native form, T-Rex preferentially binds NADH, but strategic mutagenesis of key residues in the binding pocket can switch its specificity toward NADPH [33]. Structural analyses reveal that NADP(H)-binding proteins typically contain positively charged residues that interact electrostatically with the 2'-phosphate group of NADP(H), while NAD(H)-binding proteins feature negatively charged residues in equivalent positions [33].

For the reporting domain, circularly permuted fluorescent proteins (cpFPs) have proven particularly valuable because their fluorescence properties are highly sensitive to conformational changes in the sensing domain [33] [7]. Commonly used cpFPs include cpYFP (circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein) in sensors like iNap and SoNar, and cpT-Sapphire in the newer NAPstar sensors [33] [7]. The circular permutation rearranges the FP structure such that the original N- and C-termini are connected by a short linker while new termini are created at another location in the barrel structure, making the chromophore more accessible to environmental changes.

Key Design Strategies and Optimization

Several strategic approaches have been employed to optimize the performance of redox biosensors:

Affinity tuning: By introducing specific mutations in the ligand-binding pocket, researchers have created biosensor variants with a range of dissociation constants (Kd), enabling measurements across different concentration ranges [33]. For example, the iNap family includes variants with apparent Kd values for NADPH ranging from ~1.3 µM to ~29 µM [33].

Ratiometric design: Most modern redox biosensors incorporate ratiometric measurement capabilities, either through dual-excitation or through fusion with a reference fluorescent protein of different color [33] [7]. This design minimizes artifacts caused by variations in sensor expression level, photobleaching, or cell thickness.

pH resistance: Since intracellular pH fluctuations can affect fluorescence, leading biosensors have been engineered for reduced pH sensitivity [33]. The iNap sensors, for instance, exhibit minimal fluorescence changes in response to pH variations within the physiological range [33].

Subcellular targeting: Addition of localization sequences (e.g., mitochondrial targeting sequence, nuclear localization signal) enables compartment-specific measurements [33] [36]. This has revealed striking differences in NADPH concentrations between cellular compartments, with mitochondrial matrix levels (~37 μM) significantly exceeding cytosolic levels (~3 μM) [33].

Leading NAD(P)H Biosensors and Their Characteristics

The iNap Sensor Family for NADPH Detection

The iNap (indicator for NADPH) sensors represent a breakthrough in specific NADPH monitoring [33]. Developed through structure-guided engineering of the SoNar sensor, iNap sensors feature a chimeric design combining cpYFP with the NAD(H)-binding domain of T-Rex that has been mutated to favor NADPH binding [33].

Key characteristics of iNap sensors:

- High selectivity: iNap sensors show strong responsiveness to NADPH but minimal reaction to NADH, NAD+, or NADP+ [33]

- Wide dynamic range: iNap1 exhibits an ~900% ratiometric fluorescence change upon NADPH binding [33]