Hormesis in Redox Biology: Unraveling Biphasic Mechanisms from NRF2 Signaling to Therapeutic Innovation

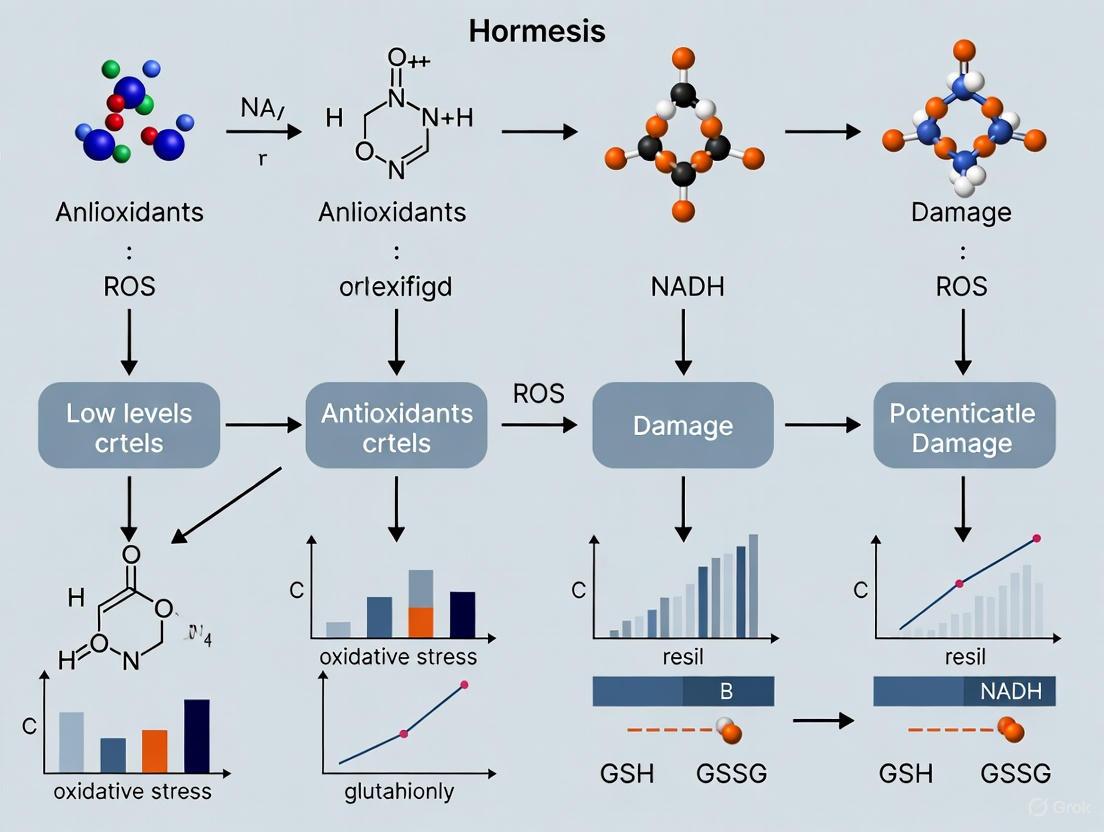

This article explores the fundamental principle of hormesis, the biphasic dose-response phenomenon where low doses of stressors induce adaptive beneficial effects, within the context of redox biology.

Hormesis in Redox Biology: Unraveling Biphasic Mechanisms from NRF2 Signaling to Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This article explores the fundamental principle of hormesis, the biphasic dose-response phenomenon where low doses of stressors induce adaptive beneficial effects, within the context of redox biology. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current evidence on how mild oxidative stress activates conserved molecular pathways, including NRF2, AMPK, and mTOR, to enhance cellular defense systems. The scope ranges from foundational mechanisms and experimental methodologies to the challenges of translating hormesis into reliable clinical applications, such as preconditioning strategies and combating therapeutic resistance. It also provides a critical comparative analysis against linear dose-response models, underscoring hormesis's profound implications for developing novel interventions in aging, degenerative diseases, and oncology.

The Redox Hormesis Paradigm: From Biphasic Dose-Response to Evolutionary Adaptation

Hormesis describes an evolutionarily conserved adaptive response where exposure to a low dose of a stressor that is damaging at higher doses induces a beneficial effect on the cell or organism [1] [2]. In redox biology, this phenomenon is characterized by a biphasic dose-response curve, typically exhibiting a J- or U-shape, where low levels of oxidative stress activate protective signaling pathways, enhancing cellular resilience [1] [3]. This whitepaper details the molecular mechanisms, quantitative parameters, and experimental methodologies underlying redox hormesis, providing a technical guide for research and therapeutic development. The core mechanistic pathways involve the activation of transcription factors like Nrf2 and NF-κB, leading to the upregulated expression of cytoprotective proteins such as antioxidant enzymes, heat-shock proteins, and growth factors [1] [4] [2]. A precise understanding of the "hormetic zone" is critical, as its boundaries define the transition from adaptive beneficial responses to detrimental oxidative damage [5] [6].

The conceptual foundation of hormesis was established by the adage of Paracelsus, "the dose makes the poison" [4] [6]. In modern toxicology, hormesis is specifically defined as "a process in which exposure to a low dose of a chemical agent or environmental factor that is damaging at higher doses induces an adaptive beneficial effect on the cell or organism" [1] [2]. This biphasic dose-response relationship is a fundamental feature observed across various biological models, from microbial systems to humans, and in response to a diverse array of stressors, including chemicals, radiation, heat, and exercise [1] [7].

Within redox biology, the hormetic response is principally triggered by mild oxidative stress, which involves a transient, non-damaging increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4] [3]. These ROS molecules function as critical signaling intermediates that activate specific cytoprotective pathways, a concept often referred to as "mitohormesis" when the signaling originates from mitochondria [3]. The resulting adaptive response enhances the cell's capacity to maintain redox homeostasis, thereby increasing its resilience to subsequent, more severe oxidative insults [8] [6]. This mechanism is integral to the health-promoting effects of several lifestyle interventions, including exercise, dietary energy restriction, and exposure to certain phytochemicals [1] [3].

Molecular Mechanisms of Redox Hormesis

The adaptive benefits of redox hormesis are mediated through the activation of highly conserved cellular signaling pathways. These pathways coordinate the expression of a network of genes responsible for antioxidant defense, detoxification, protein repair, and survival.

Core Signaling Pathways

- Nrf2/ARE Pathway: The transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) is a primary regulator of the antioxidant response. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its repressor, Keap1. Low-dose oxidative stress induces conformational changes in Keap1, leading to Nrf2 stabilization and its translocation to the nucleus. There, it binds to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), driving the expression of a battery of cytoprotective genes, including those for glutathione S-transferases, heme oxygenase-1, and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 [4] [2] [6].

- NF-κB Pathway: The transcription factor NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) is another key player. Moderate ROS levels can activate NF-κB, which promotes the expression of genes encoding anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-2 and other pro-survival factors [1] [2]. This pathway often operates in parallel with Nrf2 to ensure coordinated cell protection.

- Kinase Signaling Cascades: Several kinases are activated by hormetic stimuli. AMPK, mTOR, and MAPK pathways are involved in sensing cellular energy status and stress, thereby modulating metabolic adaptation and survival [4]. Additionally, specific isoforms of Protein Kinase C (PKC), particularly PKC-δ, can phosphorylate Nrf2, facilitating its release from Keap1 and contributing to the hormetic response [2].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated signaling network activated by mild oxidative stress, leading to cytoprotective outcomes.

Effector Molecules and Cellular Outcomes

The activation of the above signaling cascades culminates in the increased production of effector molecules that execute the protective functions:

- Antioxidant Enzymes: Enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase are upregulated, directly enhancing the cell's capacity to neutralize ROS [1] [2].

- Phase II Detoxifying Enzymes: Enzymes like NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 facilitate the elimination of toxic electrophiles [1] [6].

- Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs): Proteins such as HSP70 and HSP90 function as molecular chaperones, promoting correct protein folding and preventing aggregation under stress conditions [1] [2].

- Growth Factors: Production of factors like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) can be induced, supporting cell growth, survival, and plasticity [1].

Quantitative Characterization of the Biphasic Response

The biphasic dose-response curve of hormesis can be quantitatively modeled to define critical parameters for experimental design and interpretation.

Mathematical Modeling

The hormetic response can be effectively modeled using a Gaussian function that describes an inverted U-shaped curve [5]. The equation is: [ y = \text{baseline} + \text{amplitude} \cdot e^{-\frac{(x - x_0)^2}{2\sigma^2}} ] Where:

- ( y ) is the biological response (e.g., cell viability).

- ( \text{baseline} ) is the response level of the control.

- ( \text{amplitude} ) is the maximum stimulatory response.

- ( x_0 ) is the dose at which the peak stimulatory response occurs.

- ( \sigma ) controls the width of the hormetic zone.

A study on the flavonoid Brosimine B provided a precise quantitative example. The model fitted to retinal cell viability data yielded a peak response (( x_0 )) at 10.2 µM and a hormetic zone width (( \sigma )) of 6.5 µM, with a high coefficient of determination (( R^2 = 0.984 )), confirming a well-defined hormetic relationship [5].

Key Quantitative Parameters from Empirical Data

The table below summarizes quantitative parameters of hormetic responses from various experimental models in the literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters of Hormetic Responses in Experimental Models

| Hormetic Agent / Stressor | Biological System | Endpoint Measured | Stimulatory Dose (Peak or Range) | Maximum Stimulation (% over control) | Inhibitory Dose | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brosimine B | Avian retinal cell culture | Cell viability (under OGD) | 10 µM (Peak) | ~150% (at 10 µM) | >10 µM | [5] |

| Sulforaphane | Human mesenchymal stem cells | Cell protection / Oxidative damage | 1 µM | Protection from apoptosis & DNA damage | 20 µM (promotes damage) | [6] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Preconditioning) | L929 cell line (in vitro) | Adaptive cytoprotection | 50 µM (for 9h) | Increased resistance to severe stress | Higher, prolonged exposure | [2] |

| Olive Oil Polyphenol Extract | HeLa cells (in vitro) | Intracellular Glutathione (GSH) levels | 10-25 µg/mL (depending on extract) | Significant increase in GSH | Higher doses decreased GSH | [6] |

| Ionizing Radiation | Mice (in vivo) | Mean Lifespan | Chronic low-dose | Up to 22% extension | High, acute doses | [3] |

The "hormetic zone" is typically constrained, with the maximum stimulatory response often ranging between 30-60% above the control baseline, and the stimulatory dose range usually falling within a less than 10-fold window below the threshold for toxicity [1] [7].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Redox Hormesis

Robust experimental design is essential for accurately characterizing hormetic dose-responses. The following provides a generalized protocol and a specific example.

General Workflow for In Vitro Dose-Response Analysis

This workflow outlines the key steps for establishing a hormetic response to a chemical agent in a cell culture model.

Detailed Protocol: Brosimine B in a Retinal Neuroprotection Model

This specific protocol from recent research demonstrates the practical application of the general workflow [5].

- Cell Culture Preparation: Primary mixed retinal cells are isolated from 7-day-old chicken embryos (Gallus gallus domesticus). The retinae are dissected in a calcium and magnesium-free salt solution and cultured for 7 days in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM glutamine, and 2% penicillin-streptomycin.

- Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Model: To simulate ischemic conditions, cells are subjected to OGD by incubation in a sealed chamber for 3, 6, or 24 hours. The culture medium is replaced with glucose-free DMEM without FBS. Control cells are maintained in high-glucose (25 mM) DMEM with 10% FBS in unsealed plates.

- Hormetic Treatment: For dose-response analysis, retinal cells are treated with a range of Brosimine B concentrations (e.g., 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µM) for 24 hours. To test preconditioning (hormetic) effects, a protective dose of 10 µM Brosimine B is applied at the beginning of the OGD period.

- Cell Viability Assessment: Cell viability is quantified using the MTT assay. Cells are incubated with 0.5 mg/mL MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) for 3 hours. The resulting formazan crystals are solubilized with DMSO, and absorbance is measured at 570 nm.

- Redox Biomarker Analysis: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is measured using fluorescent probes. Antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., catalase) is assessed via specific kinetic assays.

- Computational Modeling: The biphasic dose-response data for cell viability is fitted to the Gaussian hormetic model to derive biologically interpretable parameters like the peak response dose and the hormetic zone width.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Research in redox hormesis requires a suite of specific reagents and tools to induce stress, measure responses, and probe molecular mechanisms.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Hormesis Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | A direct-acting oxidant used to induce mild oxidative stress for preconditioning experiments. | Establishing an oxidative conditioning hormesis (OCH) model (e.g., 50 µM for 9h in L929 cells) [2]. |

| Sulforaphane | A natural compound and potent Nrf2 inducer; a classic hormetic agent. | Studying Nrf2/ARE pathway activation and its role in cytoprotection at low doses (e.g., 1 µM) vs. toxicity at high doses (e.g., 20 µM) [6]. |

| MTT Assay Kit | A colorimetric method for assessing cell viability and metabolic activity, a common endpoint for hormesis. | Quantifying the biphasic effect of a test compound like Brosimine B on cell survival [5]. |

| ROS Detection Probes (e.g., DCFH-DA) | Fluorescent dyes that detect intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). | Measuring the initial ROS burst from a hormetic stressor and the subsequent reduction due to adapted antioxidant defenses [5]. |

| Nrf2 & NF-κB Antibodies | For Western Blot and Immunofluorescence to monitor the localization and expression of key transcription factors. | Confirming nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and NF-κB following low-dose oxidative stress [2]. |

| GSH/GSSG Assay Kit | For quantifying the ratio of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), a key indicator of cellular redox state. | Demonstrating the improvement in antioxidant capacity after hormetic preconditioning (e.g., with olive oil extracts) [6]. |

| Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Setup | A chamber or system to create controlled hypoxic/ischemic conditions in cell culture. | Modeling ischemic stress to test the neuroprotective hormetic effects of compounds like Brosimine B [5]. |

The biphasic dose-response curve of hormesis is a fundamental concept in redox biology, representing a highly conserved adaptive survival mechanism. Its molecular architecture, centered on the Nrf2/ARE pathway and integrated with pro-survival signals from NF-κB and kinase cascades, provides a robust framework for explaining how mild stress can enhance cellular resilience [1] [4] [2]. The quantitative characterization of the hormetic zone is not merely an academic exercise; it is critical for translating this knowledge into clinical applications.

Future research and therapeutic development must rigorously account for hormesis. In drug development, this means carefully mapping dose-response relationships to avoid underdosing, which could inadvertently induce protective responses in target diseases like cancer or infections, leading to resistance [3]. Conversely, harnessing hormesis through preconditioning strategies—such as in ischemic heart disease, neurodegenerative disorders, and metabolic diseases—holds immense promise for preventing or slowing disease progression [1] [3]. Furthermore, the hormetic effects of lifestyle interventions like exercise and dietary energy restriction provide a mechanistic understanding of their well-documented health benefits [1] [9]. As the field advances, integrating hormesis into the core of redox biology research and translational medicine will be essential for developing novel strategies to enhance healthspan and combat age-related diseases.

The concept that the effects of a substance are determined by its dosage is a cornerstone of modern pharmacology and toxicology. This principle, central to the phenomenon of hormesis—a biphasic dose-response characterized by low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition—has evolved from ancient empirical observations into a foundational concept in modern molecular biology, particularly in redox biology research [4] [10]. The journey of this idea spans from the self-experimentation of King Mithridates VI to the foundational toxicology of Paracelsus, and now to the molecular dissection of cellular signaling pathways [11]. This whitepaper traces this historical trajectory, documenting how this enduring principle has been refined through centuries of scientific inquiry to inform contemporary research and therapeutic development.

The historical narrative of hormesis provides more than just academic interest; it offers a crucial framework for interpreting modern experimental data in redox biology. Understanding this evolution is essential for today's researchers, as it contextualizes why biological systems frequently exhibit biphasic responses to oxidative stressors, phytochemicals, and therapeutic agents [12]. This report integrates historical context with current molecular understanding, providing technical guidance and methodological resources for investigating hormetic mechanisms in experimental models.

Historical Foundations of the Dose-Response Concept

Ancient and Classical Precedents

Long before the term "hormesis" was coined, the fundamental concept was recognized in various ancient philosophical and practical traditions. Key historical milestones established the foundational idea that the amount of a substance determines its biological effect:

- 8th Century BC Greek Philosophy: Hesiod, in his work Harmonia, introduced the concept of 'moderation and harmony' [11]. This philosophical principle was physically inscribed at the Apollo Temple in Delphi as 'meden agan' (μηδὲν ἄγαν), translating to 'nothing too much' [11]. Cleobulus of Lindos (625-555 BCE) further articulated the principle as 'metron ariston' (μέτρoν ἄριστoν), meaning 'the optimal is the right measure' [11].

- Roman Era Expressions: Latin proverbs such as "ne quid nimis" (nothing in excess) by Terentius and "aurea mediocritas" (the golden mean) by Horace reinforced this dosage-dependent view of substance effects [11].

- Hippocratic Contributions: Hippocrates (460-377 BCE) advanced beyond philosophical principles to practical application, recognizing individual variability in response to drugs. In the Hippocratic Corpus, he noted that "the sweet ones do not benefit everyone, nor do the astringent ones, nor are all the patients able to drink the same things," acknowledging factors such as personal "constitution" that we now understand in terms of genetic susceptibility and epigenetics [11].

Mithridates VI and Practical Toxicology

Mithridates VI Eupator (132-63 BCE), King of Pontus, represents a pivotal figure in the transition from philosophical concept to practical application of hormetic principles [11]. Fearing assassination by poisoning, he systematically experimented with poisons and antidotes, developing what would become known as mithridatism [11] [12].

Table 1: Key Components of Mithridates' Approach to Toxicology

| Aspect | Description | Modern Hormetic Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Methodology | Regular ingestion of sublethal doses of poisons, particularly arsenic [11]. | Preconditioning: Mild, intermittent exposure to a stressor to build resilience against larger, damaging exposures [11]. |

| Formula Development | Created a complex antidote known as mithridatium or theriac, containing over 50 ingredients to counteract poisons [11]. | Combination Therapies: Use of multiple compounds with synergistic protective effects, activating several defense pathways simultaneously [2]. |

| Experimental Approach | Conducted experiments on prisoners to test poisons and antidotes [11]. | Experimental Models: Use of in vitro and in vivo systems to quantify dose-response relationships and mechanisms. |

| Demonstrated Phenomenon | Acquired resistance to normally lethal doses of poison, demonstrating it at banquets [11]. | Acquired Tolerance: Adaptive responses through enzymatic induction and metabolic functional changes [11]. |

Mithridates' approach demonstrated early understanding of several principles central to modern hormesis research: tolerance development, adaptive immunity to toxins, and the paradoxical benefit of low-dose exposure to otherwise harmful substances [11]. His eventual failure to commit suicide by poison due to his acquired tolerance dramatically illustrates the effectiveness—and potential limitations—of this adaptive strategy [11].

Paracelsus and the Foundation of Modern Toxicology

The 16th-century Swiss-German physician Paracelsus (1493-1541) made the single most influential contribution to the conceptual foundation of dose-response with his seminal declaration: "Sola dosis facit venenum" ("only the dose makes the poison") [4] [13]. This statement established the fundamental principle that any substance can be toxic or beneficial depending on its concentration, moving beyond the notion of inherently "good" or "bad" compounds [13].

Paracelsus' insight provided the philosophical bridge between ancient observations of moderation and the future scientific study of dose-response relationships. His principle implicitly acknowledged what would later be termed the biphasic nature of biological responses to chemical agents, though it would take centuries for this concept to be formally developed and accepted [4].

Modern Conceptualization and Terminology

The formal scientific recognition of hormesis progressed through several key developments in the 19th and 20th centuries:

- 1880s: Arndt-Schulz Law: German pharmacologist Hugo Schulz observed that low concentrations of disinfectants paradoxically stimulated metabolism in yeast, contrary to their inhibitory effects at high concentrations [12] [10]. Initially dismissed as experimental error, this finding eventually led to the formulation of the Arndt-Schulz Law with Rudolf Arndt, proposing that weak stimuli accelerate vital activity, medium stimuli suppress it, and strong stimuli halt it [12].

- 1943: Term Coined: The term "hormesis" (from the Greek hormáein, meaning "to set in motion") was first introduced in published literature by Southam and Ehrlich in their study of red cedar tree extract effects on fungal metabolism [10] [14].

- Late 20th Century: Systematic Validation: After periods of marginalization and controversy (partly due to incorrect associations with homeopathy), the hormesis concept experienced a resurgence led by researchers including Thomas Luckey (radiation hormesis) and Edward J. Calabrese, who conducted systematic, large-scale analyses demonstrating the generality of hormetic dose responses [10].

Table 2: Historical Evolution of Key Hormesis Concepts

| Time Period | Key Figure/Concept | Contribution to Hormesis Understanding |

|---|---|---|

| 8th Century BC | Greek Proverbs ('meden agan') | Philosophical foundation of moderation and avoidance of excess [11]. |

| 1st Century BC | Mithridates VI | Practical application through systematic low-dose poison exposure (mithridatism) [11]. |

| 16th Century | Paracelsus ('Sola dosis facit venenum') | Established dose as primary determinant of toxicity/therapeutic effect [4] [13]. |

| 19th Century | Hugo Schulz & Rudolf Arndt | First experimental evidence of biphasic dose-response (Arndt-Schulz Law) [12] [10]. |

| 20th Century | Southam & Ehrlich | Coined the term "hormesis" [10]. |

| 21st Century | Calabrese et al. | Quantitative analysis, mechanistic studies, and database development [4]. |

Quantitative Characterization of Hormetic Responses

Modern research has established consistent quantitative characteristics of hormetic dose responses that transcend biological models, endpoints, and mechanisms [10]. Understanding these parameters is essential for designing experiments and interpreting results in redox biology and drug development.

Fundamental Quantitative Features

Hormetic responses display remarkably consistent quantitative properties across biological systems:

- Response Magnitude: The maximum stimulatory response in hormesis is typically modest, generally ranging between 30-60% above control/background levels, rarely exceeding two-fold [10]. This constrained amplification reflects the biological limits of plasticity and adaptive capacity.

- Dose-Response Width: The stimulatory range typically extends from approximately 0.1 to 10 times the No-Observed-Adverse-Effect Level (NOAEL) [13]. This defines the "therapeutic window" for hormetic effects.

- Temporal Dynamics: Hormetic responses can occur via either direct stimulation or overcompensation stimulation following an initial disruption in homeostasis [10]. The quantitative features are similar regardless of mechanism, but timing of measurement is critical.

Mathematical Modeling of Biphasic Responses

The biphasic nature of hormetic dose responses can be quantitatively described using mathematical models. Recent research on natural products like Brosimine B demonstrates the application of Gaussian functions to characterize these relationships [15]:

For the flavonoid Brosimine B, the dose-response relationship for retinal cell viability followed an inverted U-shaped curve effectively modeled by the equation:

Y = baseline + amplitude × e^(-(x - x₀)² / (2σ²))

Where:

- Y = measured response (cell viability)

- baseline = control response level

- amplitude = maximum hormetic enhancement

- x₀ = peak hormetic dose (10.2 µM for Brosimine B)

- σ = hormetic zone width (6.5 µM for Brosimine B) [15]

This modeling approach yielded a high coefficient of determination (R² = 0.984), confirming the hormetic response and providing biologically interpretable parameters for optimizing therapeutic applications [15].

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters of Documented Hormetic Responses

| Hormetic Agent | Biological System | Peak Stimulatory Dose | Response Magnitude | Hormetic Zone Width |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brosimine B [15] | Retinal cells (OGD model) | 10.2 µM | ~40% increased viability | σ = 6.5 µM |

| Hydrogen Peroxide [2] | L929 cell line (OCH model) | 50 µM | 30-60% increased survival | Not specified |

| General Hormetic Response [10] | Multiple models | Varies by system | Typically 30-60% increase | ~0.1-10 × NOAEL |

Molecular Mechanisms: Linking History to Modern Redox Biology

Contemporary research has revealed the sophisticated molecular machinery underlying the hormetic observations made by ancient and historical figures. The Nrf2-Keap1 antioxidant defense pathway represents a central mechanism through which mild oxidative stress activates adaptive cellular responses [4] [16] [2].

The Nrf2-Keap1 Signaling Pathway

The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway serves as a primary sensor for electrophilic and oxidative stress, coordinating the expression of numerous cytoprotective genes:

Nrf2-Keap1 Pathway Activation

This pathway explains at a molecular level the adaptive responses observed in historical practices. When Mithridates regularly consumed sublethal doses of arsenic, he was likely activating his Nrf2 pathway, enhancing the production of detoxification enzymes and antioxidant proteins that provided protection against higher, lethal doses [11] [13].

Parallel Response Mechanisms in Hormesis

Successful hormetic responses typically involve the coordinated activation of multiple protective pathways beyond just antioxidant defenses [2]. These parallel mechanisms ensure comprehensive cellular protection:

- Antioxidant Response: Activation of Nrf2 and subsequent upregulation of enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) to manage redox homeostasis [2].

- Survival Pathway Activation: Simultaneous activation of transcription factors like NF-κB, leading to increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 [2].

- Protein Quality Control: Enhanced expression of heat shock proteins (HSP70, HSP90) to maintain proper protein folding and degradation [2].

- Metabolic Adaptation: Activation of pathways such as AMPK and sirtuins that modulate energy metabolism and mitochondrial function in response to low-energy stress [4].

The integration of these parallel responses ensures that cells not neutralize oxidative damage but also enhance their repair capacity and resist apoptotic signals, creating a comprehensive adaptive response [2].

Mitohormesis and Metabolic Regulation

Mitohormesis describes the specific adaptive responses of mitochondria to mild stress, particularly relevant to redox biology [12]. Low levels of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) activate signaling pathways that enhance mitochondrial function and cellular resilience:

- Sirtuin Activation: Low-dose oxidative stress activates sirtuins (e.g., SIRT1), which deacetylate and activate transcription factors like PGC-1α, promoting mitochondrial biogenesis [4] [13].

- AMPK Signaling: Energy stress activates AMPK, which inhibits anabolic processes and promotes catabolic pathways to restore energy balance [4].

- mTOR Modulation: Hormetic stressors can transiently inhibit mTOR signaling, promoting autophagy and cellular repair mechanisms [4].

These mitochondrial adaptations illustrate how the hormesis principle operates at the subcellular level, with mild stress optimizing organelle function and contributing to systemic health benefits.

Experimental Methodologies in Hormesis Research

Establishing Oxidative Conditioning Hormesis (OCH) Models

Research into redox hormesis requires carefully controlled experimental models that mimic the mild, intermittent stress that triggers adaptive responses. The Oxidative Conditioning Hormesis (OCH) model provides a standardized approach:

Protocol: Hydrogen Peroxide OCH in L929 Cells [2]

- Cell Culture: Maintain L929 murine fibroblast cells in standard culture conditions (DMEM with 10% FBS, 37°C, 5% CO₂).

- Hormetic Conditioning: Treat cells with a low dose of H₂O₂ (50 µM) for 9 hours.

- Recovery Period: Replace medium with fresh complete medium and incubate for 24 hours.

- Challenge Exposure: Expose preconditioned cells to a normally toxic dose of H₂O₂ (typically 300-500 µM).

- Assessment: Measure cell viability (MTT assay), apoptosis markers (annexin V/PI staining), and activation of defense pathways (Nrf2 nuclear translocation, antioxidant enzyme activity).

This OCH model demonstrates the fundamental hormesis principle: pretreatment with a mild stressor enhances cellular resistance to subsequent, more severe stress [2]. The molecular mechanisms include simultaneous activation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses and NF-κB-mediated survival pathways [2].

Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Model for Neuroprotective Hormesis

The OGD model simulates ischemic conditions to study hormetic neuroprotection, particularly relevant for retinal and neuronal applications:

Protocol: Brosimine B Hormesis in Retinal Cells [15]

- Retinal Cell Culture: Prepare primary cultures of retinal cells from 7-day-old chicken embryos (Gallus gallus domesticus).

- OGD Induction:

- Transfer cells to glucose-free DMEM with low glucose (5.5 mM)

- Place in a sealed hypoxia chamber with 5% CO₂ and balanced N₂ for 3, 6, or 24 hours

- Maintain control cells in high-glucose DMEM (25 mM) in normal oxygen conditions

- Brosimine B Treatment: Apply Brosimine B across a concentration range (1-100 µM) at the beginning of the OGD period.

- Endpoint Assessments:

- Cell viability (MTT assay at 570 nm)

- ROS production (DCFH-DA fluorescence)

- Antioxidant enzyme activity (catalase, SOD assays)

- Computational modeling of dose-response using Gaussian hormetic model

This approach confirmed Brosimine B's hormetic neuroprotection, with peak efficacy at 10 µM enhancing cell viability and reducing ROS production, while higher concentrations (>10 µM) became cytotoxic [15].

OGD Experimental Workflow

In Vivo Models for Systemic Hormetic Responses

Translating cellular hormesis to whole-organism responses requires animal models that capture systemic adaptive mechanisms:

Protocol: Negative Air Ion (NAI) Exposure in Mice [8]

- Animal Subjects: Twenty 19-week-old C57BL/6J male mice divided into four groups:

- Short-term exposure (18 days NAI)

- Long-term exposure (28 days NAI)

- Corresponding control groups without NAI exposure

- NAI Exposure: Continuous exposure to NAI-enriched air generated by an air Cold Atmospheric Plasma-Nanoparticle Removal (aCAP-NR) device.

- Sample Collection: Blood and liver tissue collection after exposure period for metabolomic analysis.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Targeted metabolomics using UHPLC-MS to assess:

- Glutathione metabolism

- Lipid peroxidation products

- Purine metabolism

- Energy metabolism intermediates

This study demonstrated that NAI exposure elicits a hormetic metabolic response, with short-term exposure enhancing mitochondrial efficiency and long-term exposure inducing adaptive reprogramming, including increased inosine levels suggesting enhanced antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Models

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Models for Hormesis Research

| Reagent/Model | Application in Hormesis Research | Experimental Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide [2] | Oxidative Conditioning Hormesis (OCH) | Induces mild oxidative stress to trigger adaptive Nrf2 and NF-κB pathways | 50 µM for 9 hours in L929 cells to establish preconditioning [2] |

| Brosimine B [15] | Natural Product Hormesis | Flavonoid with biphasic effects on cell viability; model for therapeutic window determination | 10 µM for neuroprotection in retinal OGD model [15] |

| Sulforaphane [13] | Nrf2 Pathway Activation | Isothiocyanate from cruciferous vegetables; directly modifies Keap1 cysteine residues | Prototype inducer of phase II detoxification enzymes via Nrf2 [13] |

| Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) [15] | Ischemic Preconditioning Model | In vitro simulation of ischemia to study neuroprotective hormesis | 3-24 hour exposure in retinal cells to study Brosimine B effects [15] |

| Primary Retinal Cell Culture [15] | Neuronal Hormesis Model | Highly metabolically active tissue sensitive to oxidative stress; model for CNS hormesis | Avian retinal cells for studying oxidative stress neuroprotection [15] |

| L929 Fibroblast Cell Line [2] | Standardized OCH Model | Murine connective tissue cell line for reproducible oxidative conditioning studies | Hydrogen peroxide OCH model establishment [2] |

| C57BL/6J Mice [8] | In Vivo Hormesis Modeling | Well-characterized mouse strain for whole-organism metabolic and physiological adaptations | NAI exposure studies on metabolic reprogramming [8] |

The journey from Mithridatism and Paracelsus' foundational principle to contemporary molecular understanding of hormesis represents one of the most enduring narratives in biological science. What began as ancient observations of moderation and practical attempts to build poison resistance has evolved into a sophisticated framework for understanding how biological systems dynamically respond to stress through redox signaling pathways, transcriptional reprogramming, and metabolic adaptations [11] [4] [16].

For today's researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing the historical context of hormesis provides crucial insights for experimental design and therapeutic development. The consistent quantitative features of hormetic responses—their modest magnitude (typically 30-60% enhancement) and defined dose range (0.1-10 × NOAEL)—offer practical guidelines for identifying genuine hormetic effects versus experimental artifacts [10]. The molecular machinery centered around the Nrf2-Keap1 pathway provides mechanistic validation of Paracelsus' principle that "the dose makes the poison," revealing how cells distinguish between signaling and damaging levels of oxidative stress [16] [2] [13].

As redox biology continues to advance, the hormesis concept provides a unifying framework for investigating diverse phenomena—from mitochondrial adaption and inflammatory preconditioning to dietary phytochemical benefits and exercise-induced resilience [4] [8] [13]. The experimental methodologies and research tools detailed in this whitepaper offer starting points for exploring these applications across different biological systems and therapeutic areas.

The continuing evolution of hormesis from ancient observation to modern molecular mechanism underscores its fundamental importance in biology and medicine. Future research will likely refine our understanding of how these adaptive responses are integrated across organ systems and how they might be harnessed for precision medicine approaches to prevent and treat disease.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are oxygen-derived chemical molecules characterized by their reactivity. This group includes both free radicals, such as the superoxide anion (O₂•⁻) and hydroxyl radical (HO•), and non-radical species like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [17]. For decades, ROS were primarily viewed as toxic byproducts of aerobic metabolism, inflicting damage on cellular components. However, a paradigm shift has occurred with the understanding that at low levels, ROS serve as essential signaling molecules in numerous physiological processes, while at high levels, they cause oxidative distress and damage [18] [19]. This concentration-dependent dualism is a classic example of hormesis, where low-level exposure elicits an adaptive beneficial response, and high-level exposure causes harm [17].

The conceptual framework of redox biology posits that the intracellular redox potential is a tightly regulated homeostatic parameter. The balance between pro-oxidant generation and antioxidant defenses determines the cellular outcome [17]. This review will delve into the molecular mechanisms of ROS as signaling messengers and toxic agents, frame this duality within the hormesis model, and provide researchers with the quantitative data and methodological tools essential for probing this complex field.

Molecular Mechanisms: From Signaling to Damage

ROS as Second Messengers in Redox Signaling

At low, physiological concentrations (typically in the nanomolar range for H₂O₂), ROS function as pivotal second messengers in redox signaling [19]. A primary mechanism involves the reversible oxidation of cysteine residues within proteins. At physiological pH, certain cysteine residues exist as a thiolate anion (Cys-S⁻), making them highly susceptible to oxidation by H₂O₂ to form sulfenic acid (Cys-SOH) [19]. This modification can alter protein function, activity, and interaction.

A canonical example is the signaling cascade initiated by growth factors such as Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF) and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF). Their binding to Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs) activates NADPH oxidases (NOX), which generate a localized burst of O₂•⁻, rapidly dismutated to H₂O₂ [19]. This H₂O₂ then reversibly oxidizes and inactivates protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) like PTP1B, as well as the lipid phosphatase PTEN. The transient inhibition of these negative regulators reinforces and prolongs the activation of downstream pro-growth and pro-survival pathways, such as PI3K-AKT and RAS-MEK-ERK [19]. The redox signal is terminated when enzymes like thioredoxin (TRX) reduce the oxidized cysteine back to its thiol state, demonstrating the precise and reversible nature of this regulation [17] [19].

The Transition to Oxidative Stress and Damage

When ROS generation overwhelms the antioxidant capacity of the cell—a state of oxidative distress—the same chemical properties that enable signaling lead to irreversible damage [17]. The sulfenic acid modification on cysteines can be further oxidized to sulfinic (Cys-SO₂H) and sulfonic (Cys-SO₃H) acids, which are often irreversible and lead to permanent protein dysfunction [19].

Furthermore, highly reactive species like the hydroxyl radical (HO•), produced via the Fenton reaction between H₂O₂ and ferrous iron (Fe²⁺), can indiscriminately attack all major classes of macromolecules [19]. This results in:

- Lipid peroxidation: Damaging cell membranes and generating reactive aldehydes that can propagate injury [20].

- Protein carbonylation: Irreversibly modifying proteins, leading to loss of function and aggregation [20].

- DNA damage: Causing strand breaks and base modifications, which can lead to genomic instability [20] [19].

This oxidative damage to biomolecules is a hallmark of numerous chronic diseases and contributes to the aging process [17] [21].

Table 1: Key Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Roles in Signaling and Damage

| ROS | Chemical Nature | Primary Sources | Signaling Role | Damaging Actions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Free radical | Mitochondrial ETC, NOX enzymes | Limited; precursor for H₂O₂, can inactivate Fe-S cluster proteins | Inactivates Fe-S cluster enzymes, precursor to more reactive species |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Non-radical | SOD action on O₂•⁻, NOX | Major redox messenger; reversibly oxidizes protein cysteine thiols | Precursor to HO•, can cause irreversible protein overoxidation |

| Hydroxyl Radical (HO•) | Free radical | Fenton reaction (H₂O₂ + Fe²⁺) | None; too reactive and non-specific | Indiscriminate oxidation of lipids, proteins, and DNA |

The following diagram illustrates the central hormesis concept of ROS, showing the transition from physiological signaling to pathological damage as concentrations increase.

The Hormetic Framework in Redox Biology

The biphasic dose-response of ROS is a textbook example of hormesis. Hormesis in redox biology refers to the phenomenon where mild, subtoxic levels of ROS induce an adaptive, protective resilience in cells and tissues [17]. This "pre-conditioning" effect is achieved through the stimulation of redox-sensitive signaling pathways that lead to:

- Upregulation of antioxidant defenses: Increased expression of enzymes like superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and peroxiredoxins (Prx) via transcription factors such as Nrf2 [17].

- Stimulation of repair mechanisms: Enhanced systems for clearing and repairing damaged proteins and DNA.

- Promotion of cell survival and proliferation: Activation of growth-promoting pathways [17].

Conversely, supraphysiological ROS production exhausts these adaptive systems, leading to the damaging consequences of oxidative distress [17]. The GSH/GSSG ratio is one of the most reliable markers of this intracellular redox equilibrium, shifting towards a more oxidized state under distress [17]. The therapeutic implication is profound: strategies aiming to broadly suppress all ROS with high-dose antioxidants may inadvertently blunt beneficial hormetic signaling, whereas approaches that modulate ROS or boost the endogenous antioxidant response may be more successful [17].

Quantitative Data: Measuring ROS and Oxidative Stress

Quantifying ROS is methodologically challenging due to their high reactivity, short half-lives, and low steady-state concentrations [20]. The choice of technique depends on the specific research question, including the ROS of interest, desired spatial and temporal resolution, and the biological system.

Table 2: Quantitative Methods for ROS Detection and Analysis

| Method | Principle | Key Metrics | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Direct detection of unpaired electrons in radical species using spin traps. | Absolute concentration of radical species (e.g., in capillary blood) [20]. | "Gold standard" for direct ROS measurement; validated in human studies comparing healthy vs. diseased states [20]. | Provides a snapshot of "instantaneous" ROS production; can be technically complex. |

| Fluorescent Probes (e.g., DCFH-DA) | Oxidation of non-fluorescent probe to a fluorescent product by ROS. | Relative fluorescence intensity, proportional to cellular ROS levels. | Cell-based assays, flow cytometry; high-throughput screening. | Susceptible to artifacts (e.g., auto-oxidation); semi-quantitative. |

| Histochemical Staining (DAB, NBT) | ROS-mediated precipitation of colored dyes (brown for DAB/H₂O₂, blue for NBT/O₂•⁻). | Staining area and intensity, quantified by image analysis [22]. | Spatial distribution of ROS in tissues (e.g., plant leaves, histological sections) [22]. | Qualitative to semi-quantitative; requires careful validation and image analysis. |

| Two-Photon Microscopy (TP-FRIM/TP-FLIM) | Ratiometric (FRIM) or fluorescence lifetime (FLIM) imaging of redox-sensitive probes. | Spatial distribution and quantification of specific redox couples (e.g., GSH:GSSG) [23]. | Intravital imaging of deep tissues; high spatiotemporal resolution of redox state [23]. | Requires specialized equipment and genetically encoded or chemical probes. |

Experimental Protocols for ROS Research

Protocol: Direct ROS Measurement in Human Blood Using EPR

This microinvasive method allows for the direct quantification of ROS production rates in capillary blood and has been applied to compare different physiological and pathological states [20].

- Sample Collection: Collect approximately 50 μL of capillary blood from a fingertip into a heparinized capillary tube. Alternatively, 3 mL of venous blood can be drawn from an antecubital vein into heparinized Vacutainer tubes [20].

- Sample Preparation:

- For venous blood, separate plasma by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- After plasma removal, carefully collect aliquots of red blood cells (RBCs), discarding the buffy coat.

- Immediately transfer 50 μL of capillary blood, venous whole blood, plasma, or RBCs to EPR analysis.

- EPR Analysis: Mix the blood sample with a spin trap solution (e.g., CMH spin trap). The spin trap reacts with short-lived radicals to form more stable, detectable adducts.

- Data Acquisition and Quantification: Record the EPR spectrum. The amplitude of the EPR signal is proportional to the concentration of the radical adduct, allowing for the calculation of the absolute ROS production rate. Studies show a significant linear relationship between ROS measured in capillary blood and venous blood/plasma/RBCs, validating the capillary method [20].

Protocol: Imaging ROS in Plant Leaves via Histochemistry and Automated Image Analysis

This protocol details the visualization and quantification of H₂O₂ and O₂•⁻ in plant leaves using histochemical staining and automated analysis via the Fiji (ImageJ) platform [22].

- Leaf Staining:

- For H₂O₂ detection: Infiltrate leaves with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (1 mg/mL, pH 3.8). Incubate in the dark for 4-8 hours. H₂O₂ polymerizes DAB, producing a brown precipitate [22].

- For O₂•⁻ detection: Infiltrate leaves with nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) solution (0.1 mg/mL in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.8). Incubate in the dark for 30-90 minutes. O₂•⁻ reduces NBT to an insoluble blue formazan precipitate [22].

- Destaining and Preservation: After staining, clear the leaves by boiling in 96% ethanol for 10 minutes to remove chlorophyll, which masks the staining. Store the destained leaves in 50% glycerol [22].

- Image Acquisition: Scan the destained leaves using a flatbed scanner at a standard resolution (e.g., 600 DPI).

- Automated Image Analysis with Fiji:

- Open the leaf image in Fiji.

- Use the Trainable Weka Segmentation (TWS) plugin. Manually label representative areas of the stained regions and the unstained leaf background on a subset of images to train a pixel classifier.

- Apply the trained classifier to all images to segment and identify stained (ROS-positive) pixels automatically.

- Quantify the results as the percentage of the total leaf area that is stained. This method has shown high accuracy (Dice Similarity Coefficient ≈ 0.92) compared to manual assessment [22].

The workflow for this automated image analysis is summarized below.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Redox Biology

| Tool / Reagent | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CMH Spin Trap | Cyclic hydroxylamine that reacts with O₂•⁻ and other radicals to form stable nitroxides detectable by EPR. | Direct quantification of superoxide production rates in biological samples like blood [20]. |

| DAB (3,3'-Diaminobenzidine) | Chromogen that polymerizes to a brown precipitate in the presence of H₂O₂ and peroxidase. | Histochemical staining for visualizing spatial distribution of H₂O₂ in tissues (e.g., plant leaves) [22]. |

| NBT (Nitro Blue Tetrazolium) | Yellow-colored tetrazolium salt reduced to insoluble blue formazan by O₂•⁻. | Histochemical staining for detecting superoxide anion localization in tissues and cells [22]. |

| Genetically Encoded Sensors (e.g., roGFP, HyPer) | Fluorescent proteins whose excitation/emission properties change upon oxidation or binding to specific ROS (e.g., H₂O₂). | Real-time, compartment-specific monitoring of redox dynamics in live cells [23]. |

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) | Precursor for glutathione (GSH) synthesis; acts as a broad-spectrum antioxidant. | Experimentally modulating cellular redox state to test the role of ROS in signaling pathways [19]. |

| NADPH Oxidase (NOX) Inhibitors (e.g., VAS2870, Apocynin) | Pharmacological agents that inhibit specific sources of ROS generation. | Dissecting the contribution of NOX-derived ROS vs. mitochondrial ROS in cellular processes [17]. |

The understanding of reactive oxygen species has evolved from a monolithic view of them as purely toxic agents to a nuanced appreciation of their dual role governed by the hormesis principle. Low, finely controlled concentrations of ROS are indispensable for physiological signaling, regulating processes from growth to immunity. Conversely, a loss of this control leads to oxidative stress, which is implicated in a myriad of diseases and aging. The future of therapeutic intervention in this field lies not in the non-selective scavenging of all ROS, but in the precise modulation of redox pathways—either by boosting endogenous antioxidant systems in states of deficiency or by selectively inducing ROS in contexts like cancer therapy to push malignant cells beyond their redox tolerance [17]. Mastering this delicate balance is the next frontier in redox biology and medicine.

The Oxygen Paradox and Evolutionary Conservation of Redox Adaptive Responses

The Oxygen Paradox describes the fundamental biological contradiction wherein oxygen, while indispensable for aerobic life, generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage vital cellular structures and contribute to aging and disease [24]. This paradox is resolved through evolutionarily conserved redox adaptive responses known as hormesis, wherein low-dose oxidative stress activates protective signaling pathways that enhance cellular resilience. These adaptive mechanisms, observed from bacteria to humans, involve sophisticated sensing of redox imbalances and activation of genes coordinating antioxidant defense, protein homeostasis, and metabolic reprogramming. This whitepaper examines the molecular underpinnings of these conserved pathways, their quantitative dynamics, and their implications for therapeutic development, providing researchers with methodological frameworks for investigating redox biology in experimental and clinical contexts.

The Oxygen Paradox represents a foundational concept in redox biology, capturing the dual nature of oxygen as both essential for energy metabolism and inherently dangerous due to its conversion to reactive species [24]. This paradox emerged evolutionarily approximately 2.5 billion years ago with the Great Oxidation Event, which forced organisms to develop sophisticated antioxidant networks to mitigate oxygen toxicity while harnessing its metabolic potential [25]. The resolution to this paradox lies in the phenomenon of hormesis—an adaptive response where exposure to low doses of a stressor induces resistance to higher, potentially toxic doses of the same or similar stressors [4].

Hormetic responses follow a characteristic biphasic dose-response curve, typically J-shaped or inverted U-shaped, where low doses stimulate beneficial adaptations while high doses cause damage [4]. In redox biology, this manifests as adaptive homeostasis, wherein transient expansion of the homeostatic range occurs in response to subtoxic oxidative signaling molecules [24]. The mechanistic basis involves activation of conserved redox-sensitive transcription factors, enhancement of antioxidant systems, and remodeling of proteostatic networks [24] [4]. Understanding these evolutionarily conserved mechanisms provides crucial insights for developing interventions targeting age-related diseases, cancer, and degenerative disorders where redox imbalance is a pathological feature.

Evolutionary Conservation of Redox Adaptation

Phylogenetic Evidence and Molecular Mechanisms

The molecular machinery governing redox adaptation demonstrates remarkable evolutionary conservation from simple organisms to humans. The glutathione (GSH) system, a pivotal component of the antioxidant network, appears across phylogeny, with homologous synthesis and utilization pathways in bacteria, plants, invertebrates, and mammals [25]. Even phototrophic bacteria possess GSH synthesis capabilities, indicating the ancient origin of this redox buffering system [25]. The preparation for oxidative stress (POS) hypothesis further demonstrates this conservation, documenting 83 animal species across 8 phyla that upregulate antioxidant defenses during hypoxia to prepare for reoxygenation stress [26].

At the molecular level, key redox-sensing transcription factors show striking conservation:

- The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway (or its orthologs) is conserved from Drosophila (CncC-Keap1) to vertebrates, regulating proteasome expression and oxidative stress resistance [24]

- Hypoxia-inducible factors mediate oxygen sensing across metazoans

- NF-κB and FoxO pathways integrate redox signals in immune and stress responses from insects to mammals

These conserved pathways enable organisms to dynamically adjust their antioxidant capacity based on oxidative challenges, representing a fundamental adaptation to the Oxygen Paradox [25] [26].

Temporal Adaptation Patterns

Redox adaptation mechanisms operate across different timescales, from rapid post-translational modifications to long-term evolutionary adaptations:

Table 1: Timescales of Redox Adaptive Mechanisms

| Timescale | Adaptive Mechanism | Key Components | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seconds-Minutes | Enzyme modification | GST oxidation, γGCS activation | Immediate antioxidant enhancement |

| Hours-Days | Transcriptional activation | Nrf2 translocation, ARE activation | Increased antioxidant gene expression |

| Days-Weeks | Epigenetic modification | DNA methylation, histone changes | Sustained adaptive phenotypes |

| Generations | Genomic evolution | Gene selection, pathway refinement | Species-level adaptation |

The short-term adaptations include direct oxidation of glutathione-S-transferases, enhancing their activity, and oxidation-induced conformational changes in γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase relieving feedback inhibition to boost GSH synthesis [25]. On an intermediate timescale, ROS oxidize specific cysteine residues (Cys273, 288, 151) on Keap1, promoting Nrf2 nuclear translocation and antioxidant response element-mediated gene expression [25]. Long-term adaptations occur through epigenetic modifications and selective pressures on genomic sequences, fine-tuning redox regulatory networks over evolutionary timescales [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Redox Adaptive Responses

Redox Potentials and Homeostatic Ranges

Quantitative redox biology provides crucial insights into the dynamics of adaptive responses. The redox state of key thiol couples, particularly the GSSG/2GSH couple, serves as an important indicator of cellular redox environment, best assessed using the Nernst equation:

[ E_{hc} = -252 - \frac{61.5}{2} \log \frac{[GSH]^2}{[GSSG]} \text{ in mV at } 37^\circ C, \text{pH} = 7.2 ]

where (E_{hc}) represents the half-cell reduction potential [27]. Notably, the absolute concentration of GSH significantly influences interpretation—a cell with 10 mM GSH requires a [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio of only 16.6 to achieve the same -228 mV potential as a cell with 1 mM GSH needing a ratio of 166 [27]. This quantitative understanding is essential for comparing redox states across different experimental systems and biological states.

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Redox Adaptive Responses

| Parameter | Typical Range | Measurement Significance | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio | 1-100 mM (GSH), <1% GSSG | Major cellular redox buffer | Total GSH concentration affects ratio interpretation |

| H₂O₂ flux | Nanomolar signaling range | Secondary messenger concentration | Spatial compartmentalization critical |

| Mitochondrial ROS | ~0.2% O₂ conversion | Primary endogenous ROS source | Electron availability limits production |

| Nrf2 activation | Picomolar-nanomolar inducer | Adaptive homeostasis trigger | Different from toxic millimolar concentrations |

| Antioxidant induction | 30-80% increase in POS | Protection magnitude | Transient, returns to baseline post-challenge |

The Superoxide-Peroxide Removal System

The superoxide-peroxide removal (SPR) system forms the core network balancing ROS generation and elimination [27]. This system comprises several interconnected enzymes:

- Superoxide dismutases convert O₂•⁻ to H₂O₂

- Catalase decomposes H₂O₂ to H₂O and O₂

- Glutathione peroxidases reduce H₂O₂ and lipid peroxides using GSH

- Peroxiredoxins eliminate H₂O₂, organic hydroperoxides, and peroxynitrite

- Thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems regenerate oxidized protein thiols

The SPR system exhibits organelle-specific isoforms that maintain compartmentalized redox environments, with mitochondrial (MnSOD), cytosolic (CuZnSOD), and extracellular SOD isoforms performing specialized functions [27]. Quantitative analysis reveals that mitochondrial MnSOD concentration can be 10-fold higher in the mitochondrial matrix than cytosolic CuZnSOD concentration, despite similar activity units, highlighting the importance of absolute quantification over relative measurements [27].

Methodologies for Investigating Redox Adaptive Responses

Experimental Models and Protocols

Investigation of the Oxygen Paradox and redox adaptation employs diverse model systems and methodological approaches:

Invertebrate Models:

- Drosophila melanogaster: Studies demonstrate age-dependent decline in adaptive homeostasis, with young flies showing H₂O₂ stress adaptation and increased Lon protease expression, while old flies lose this capacity [24]. Transgenic Nrf2 (CncC) activation in young flies upregulates proteasome expression and confers proteotoxic stress resistance.

Mammalian Cell Systems:

- Human Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs): The "normobaric oxygen paradox" model exposes cells to varying oxygen concentrations (30%, 100%, 140% O₂) followed by return to normoxia, measuring time-dependent activation of HIF-1α, Nrf2, and mitochondrial biogenesis factors [28].

- Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitor Cells: Redox proteomic analyses compare fetal versus adult cells, identifying 4,438 cysteine residues with differential oxidation susceptibility, highlighting ontogenic changes in redox regulation [29].

POS Induction Protocol:

- Subject organisms to mild hypoxia (2-8 hours, depending on species)

- Maintain at reduced oxygen tension (1-5% O₂)

- Monitor antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, catalase, GST) during hypoxia and reoxygenation

- Assess oxidative damage markers (protein carbonylation, lipid peroxidation)

- Measure phosphorylation status of redox-sensitive kinases

This protocol typically yields 30-80% increases in antioxidant activities during hypoxia, which return to baseline during reoxygenation [26].

Redox Proteomics and Quantitative Mass Spectrometry

Quantitative redox proteomics enables comprehensive mapping of reversible cysteine oxidation across the proteome:

Workflow:

- Cell lysis under non-reducing conditions with alkylating agents

- Protein digestion with trypsin

- Enrichment of oxidized peptides using thiol-affinity techniques

- LC-MS/MS analysis with isotopic labeling for quantification

- Bioinformatic analysis to identify redox-sensitive cysteine residues

This approach identified ontogenic changes in oxidation state of thiols acting in mitochondrial respiration and protein homeostasis during hematopoietic development and MLL-ENL leukemogenesis [29]. The technology enables detection of specific oxidative post-translational modifications including S-glutathionylation, S-nitrosylation, and sulfenic acid formation that function as redox switches in signaling [30].

Signaling Pathways in Redox Adaptation

The Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Pathway

The Nrf2-Keap1 pathway represents the master regulator of antioxidant gene expression and is highly conserved in redox adaptation:

Pathway Mechanism: Under basal conditions, Keap1 targets Nrf2 for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. During oxidative stress, specific cysteine residues (Cys151, 273, 288) on Keap1 become oxidized, causing conformational changes that disrupt Nrf2 ubiquitination. Stabilized Nrf2 translocates to the nucleus, heterodimerizes with small Maf proteins, and binds to Antioxidant Response Elements upstream of genes encoding GST, GSH synthesizing enzymes, NADPH-quinone oxidoreductase, and heme oxygenase-1 [24] [30]. This pathway exemplifies adaptive homeostasis by transducing subtoxic oxidative signals into protective gene expression.

Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Redox Adaptation

Mitochondrial biogenesis integrates with redox adaptation through coordinated regulation by PGC-1α, Nrf2, and TFAM:

Regulatory Network: The normobaric oxygen paradox demonstrates that pulsed hyperoxia (30-140% O₂) activates PGC-1α nuclear translocation, which coactivates Nrf2 expression [28]. Nrf2 then induces NRF1 expression, which together with PGC-1α activates mitochondrial transcription factor A expression, driving mitochondrial biogenesis [28]. This coordinated response enhances mitochondrial quality and function, improving cellular capacity to manage oxidative challenges. The specificity of response varies with oxygen dose—mild hyperoxia (30% O₂) robustly induces TFAM expression, while higher doses (100-140% O₂) show attenuated effects despite PGC-1α activation [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Models

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Biology Investigations

| Reagent/Model | Application | Key Function | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drosophila melanogaster | Aging studies, genetic screens | Conserved Nrf2 ortholog (CncC) | Age-dependent response differences |

| Human PBMCs | Normobaric oxygen paradox | HIF-1α and Nrf2 activation | Dose-dependent response to O₂ levels |

| NADPH oxidase inhibitors | ROS source identification | Selective blockade of enzymatic ROS | Compartment-specific effects |

| Nrf2 activators | Hormesis induction | Subtoxic pathway priming | Concentration-critical window |

| GSH/GSSG probes | Redox potential measurement | Quantitative assessment with Nernst equation | Absolute concentration matters |

| Redox proteomics | Cysteine oxidation mapping | Identification of redox-sensitive proteins | Preservation of oxidation state |

| POS animal models | Hypoxia-tolerant species | Natural hormesis models | Tissue-specific antioxidant responses |

The Oxygen Paradox continues to frame our understanding of redox biology, with evolutionarily conserved adaptive responses providing protection against oxidative challenges. The field is advancing toward quantitative redox biology that integrates absolute measurements of reactive species, redox potentials, and reaction kinetics to model network behavior [27]. Future research will leverage single-cell redox imaging to resolve spatial compartmentalization of signaling, cryo-EM to visualize redox-sensitive protein complexes, and multi-omics integration to map systems-level responses to oxidative challenges.

Therapeutic applications targeting redox adaptation mechanisms show promise in preclinical models, with NRF2 activators in clinical trials for chronic kidney disease and neurodegenerative disorders [30]. However, the hormetic principle necessitates precise dosing, as excessive NRF2 activation promotes tumor growth in some contexts [24] [30]. The emerging paradigm recognizes ROS as specific signaling molecules rather than mere toxic byproducts, suggesting future therapies will target specific redox-sensitive nodes rather than applying blanket antioxidant approaches [17] [30]. This refined understanding of the Oxygen Paradox and its evolutionary solutions continues to inspire novel therapeutic strategies for diseases of aging and metabolism.

This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of the glutathione (GSH) system and redox-sensitive transcription factors, framing their interplay within the mechanistic context of hormesis in redox biology. The tripeptide glutathione serves as the central coordinator of cellular redox homeostasis, while transcription factors including Nrf2, NF-κB, and AP-1 function as molecular sensors that translate oxidative challenges into adaptive genetic responses. We examine how low-level oxidative stress activates these pathways to enhance cellular resilience—a phenomenon fundamental to hormesis. The content includes detailed experimental methodologies, structured quantitative data comparisons, and visual representations of signaling pathways to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the intersection of redox biology and therapeutic development.

The Glutathione (GSH) System: Architecture and Functions

Biochemical Fundamentals and Homeostasis

Glutathione (γ-L-glutamyl-L-cysteinyl-glycine) represents the most abundant low-molecular-weight thiol in biological systems, functioning as the primary redox buffer against oxidative and nitrosative stress [31]. Its reducing power resides in the thiol (-SH) group of its cysteine residue, which serves as an electron donor in redox reactions. The glutathione system maintains a dynamic equilibrium between reduced (GSH) and oxidized (GSSG) forms, with physiological GSH:GSSG ratios typically ranging from 10:1 to 100:1 in various cellular compartments [31]. This redox couple exists in a metastable state rather than a true equilibrium, with its reducing power maintained through enzymatic catalysis rather than spontaneous reactions [32].

Cellular glutathione distribution follows a compartment-specific pattern: approximately 90% resides in the cytosol (the primary site of synthesis), with the remainder distributed to mitochondria, nucleus, and endoplasmic reticulum [31]. The endoplasmic reticulum uniquely maintains a more oxidized environment where GSSG predominates, supporting disulfide bond formation during protein folding [31]. This subcellular partitioning enables compartment-specific redox regulation tailored to organellar functions.

Table 1: Glutathione System Components and Characteristics

| Component | Characteristics | Localization | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSH | Tripeptide (Glu-Cys-Gly); 1-10 mM concentration | Cytosol, mitochondria, nucleus | Redox buffering, detoxification, peroxide scavenging |

| GSSG | Disulfide-linked dimer; <10% of total GSH pool | All compartments, enriched in ER | Oxidized storage form; protein disulfide formation |

| GCL | Heterodimer (GCLC + GCLM); rate-limiting enzyme | Cytosol | Catalyzes γ-glutamylcysteine formation from Glu and Cys |

| GS | Homodimer; ATP-dependent | Cytosol | Adds glycine to γ-glutamylcysteine to form GSH |

| GR | NADPH-dependent flavoenzyme | Cytosol, mitochondria | Reduces GSSG back to GSH, maintaining reduced pool |

| GGT | Membrane-bound heterodimeric glycoprotein | Plasma membrane (kidney, biliary, brain) | Initiates extracellular GSH degradation and recycling |

Synthesis, Regulation, and Recycling

Glutathione biosynthesis occurs through two consecutive ATP-dependent enzymatic reactions [31]. The first and rate-limiting step is catalyzed by glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL), a heterodimeric enzyme composed of catalytic (GCLC) and modulatory (GCLM) subunits that forms an unusual γ-peptide bond between glutamate and cysteine. The second reaction, catalyzed by glutathione synthetase (GS), adds glycine to form the complete tripeptide. Multiple factors control GSH synthesis, including substrate availability (particularly L-cysteine), GCL subunit expression ratios, feedback inhibition of GCL by GSH, and ATP provision [31].

The glutathione reduction-recycling system maintains the reduced GSH pool through NADPH-dependent enzymes. Glutathione reductase (GR) catalyzes the reduction of GSSG back to GSH, consuming NADPH in the process [33]. In fission yeast (and homologs in higher eukaryotes), GR (Pgr1) demonstrates dual cytosolic and mitochondrial localization, with mitochondrial GR being particularly essential for maintaining redox balance in that compartment [33]. The thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems provide complementary electron donor pathways that work in concert with glutathione to maintain cellular reducing conditions [33].

Molecular Mechanisms of Redox Regulation

Glutathione participates in redox regulation through multiple mechanistic pathways. It directly scavenges reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) through non-enzymatic reactions and serves as an essential cofactor for glutathione peroxidase (GPX) in the reduction of hydroperoxides [31]. Perhaps most significantly, glutathione mediates reversible post-translational protein modifications through S-glutathionylation—the formation of mixed disulfides between protein cysteinyl residues and glutathione [31].

Unlike spontaneous thermodynamic equilibration, protein S-glutathionylation is enzymatically controlled, primarily by glutaredoxins (Grxs) and certain glutathione S-transferases, which catalyze both the addition and removal of glutathione moieties [32]. This enzymatic control ensures specificity and appropriate reaction kinetics for signaling purposes. Through this mechanism, glutathione regulates numerous cellular processes including DNA synthesis via ribonucleotide reductase, apoptosis via caspase-3 modulation, and vessel formation via sirtuin 1 regulation [32].

Redox-Sensitive Transcription Factors: Molecular Sensors and Effectors

Redox-sensitive transcription factors function as molecular sensors that convert changes in cellular redox state into altered gene expression patterns. These factors contain critical cysteine residues that undergo reversible oxidative modifications, leading to conformational changes, altered DNA binding affinity, or modified interactions with regulatory proteins [34]. The primary transcription factors involved in redox sensing include Nuclear Factor-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2), Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and Activator Protein-1 (AP-1), each responding to distinct but overlapping redox signals.

Table 2: Redox-Sensitive Transcription Factors and Functions

| Transcription Factor | Redox Sensor | Target Genes | Biological Functions | Role in Hormesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nrf2 | Cysteine residues in Keap1 | ARE-driven genes: antioxidant enzymes, phase II detoxification enzymes | Antioxidant defense, detoxification, metabolic adaptation | Primary mediator of adaptive responses to low-dose stressors |

| NF-κB | Cysteine residues in IKK complex and DNA-binding domains | Pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules | Inflammation, immune response, cell survival | Biphasic response: low doses enhance defense, high doses promote damage |

| AP-1 | Redox-sensitive cysteine residues in Fos/Jun subunits | Matrix metalloproteinases, cyclin D1, pro-inflammatory genes | Cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis | Context-dependent modulation of stress responses |

| HIF-1α | Oxygen-dependent degradation domain; redox-sensitive | Glycolytic enzymes, VEGF, erythropoietin | Angiogenesis, metabolic adaptation to hypoxia | Links oxygen sensing to redox adaptation |

Nrf2-Keap1-ARE Pathway: Master Regulator of Antioxidant Defense

The Nrf2-Keap1 system represents the primary cellular defense mechanism against oxidative and electrophilic stress [34] [30]. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm by its inhibitor Keap1, which targets Nrf2 for constitutive ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Oxidative stress or exposure to electrophilic compounds triggers conformational changes in Keap1 through modification of specific cysteine residues, leading to Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation [13]. In the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to Antioxidant Response Elements (AREs) in the promoter regions of over 500 cytoprotective genes [30].

Nrf2 target genes include those encoding antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase), glutathione synthesis enzymes (GCL, GS), phase II detoxification enzymes (glutathione S-transferases, NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase), and proteins involved in glutathione regeneration [30] [35]. This coordinated gene expression program enhances cellular capacity to neutralize reactive species, eliminate electrophilic toxins, and maintain redox homeostasis. The Nrf2 pathway is particularly significant in hormesis, as many hormetic compounds (e.g., sulforaphane, curcumin, quercetin) act through this mechanism to induce adaptive protection [13].

NF-κB Pathway: Inflammatory Signaling and Redox Control

NF-κB comprises a family of Rel-related transcription factors that serve as critical regulators of inflammatory and immune responses [36]. In unstimulated cells, NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitory IκB proteins. Various stimuli, including ROS, RNS, and inflammatory cytokines, activate the IκB kinase (IKK) complex, which phosphorylates IκB, leading to its ubiquitination and degradation [36]. This process liberates NF-κB, allowing its translocation to the nucleus and binding to κB enhancer elements in target genes.

NF-κB regulates the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [36] [35]. The pathway demonstrates complex redox sensitivity, with low levels of ROS potentially activating NF-κB while higher levels may inhibit its DNA-binding activity through oxidation of critical cysteine residues [36]. This biphasic response pattern positions NF-κB as a key mediator in hormetic processes, particularly those involving inflammatory preconditioning.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Assessing Glutathione System Status

Comprehensive evaluation of the glutathione system requires multiple complementary approaches to capture its dynamic nature:

GSH/GSSG Quantification: Accurate measurement of reduced and oxidized glutathione remains fundamental to assessing cellular redox status. The standard protocol involves rapid acid extraction (typically with perchloric or metaphosphoric acid) to prevent artifactual oxidation during sample processing, followed by derivatization with fluorescent tags such as monobromobimane and separation with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection [31]. This method allows simultaneous quantification of GSH, GSSG, and mixed disulfides with sensitivity in the picomole range. Care must be taken to minimize auto-oxidation during sample preparation through rapid processing and acid stabilization.

Enzymatic Activity Assays: Glutathione-related enzyme activities provide functional readouts of system capacity. Glutathione reductase activity is measured by monitoring NADPH oxidation at 340 nm during the reduction of GSSG to GSH [33]. Glutathione peroxidase activity is typically assayed using hydrogen peroxide or cumene hydroperoxide as substrates, coupled with NADPH consumption through the glutathione reductase reaction [31]. Glutamate-cysteine ligase activity, representing the rate-limiting step in GSH synthesis, is measured by following the formation of γ-glutamylcysteine using HPLC or colorimetric methods [31].

Compartment-Specific Redox Probes: Genetically encoded fluorescent probes such as roGFP (redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein) fused to glutaredoxin provide compartment-specific measurements of glutathione redox potential (EGSH) in real-time within living cells [32]. These probes utilize the equilibrium between roGFP and glutaredoxin to report on the GSH:GSSG ratio, allowing dynamic monitoring of redox changes in specific organelles such as mitochondria or endoplasmic reticulum.

Monitoring Transcription Factor Activation

Nuclear Translocation Assays: Transcription factor activation is commonly assessed through subcellular localization studies. Immunofluorescence staining followed by confocal microscopy allows visual determination of Nrf2 or NF-κB translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus [34] [35]. Quantitative image analysis provides statistical data on activation kinetics. Alternatively, cellular fractionation followed by Western blotting of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts offers a biochemical approach to quantify distribution changes.

DNA-Binding Activity Measurements: Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) using radiolabeled oligonucleotides containing ARE or κB sequences assess the DNA-binding capacity of transcription factors in nuclear extracts [35]. Supershift assays with specific antibodies confirm protein identity. For higher throughput, ELISA-based DNA-binding assays commercialize this approach with colorimetric or fluorescent readouts.

Transcriptional Activity Reporter Systems: Luciferase reporter constructs under the control of ARE or κB promoter elements provide sensitive, dynamic measurements of transcription factor activity [35]. Stable cell lines with integrated reporters enable long-term studies and compound screening. Simultaneous use of multiple reporters with different promoters allows specificity assessment.