Genetically Encoded Redox Probes: A Comprehensive Guide to Fabrication, Imaging, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the fabrication and application of genetically encoded redox probes.

Genetically Encoded Redox Probes: A Comprehensive Guide to Fabrication, Imaging, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the fabrication and application of genetically encoded redox probes. It covers the foundational principles of sensor design, from the structure of fluorescent proteins to the engineering of molecular switches for specific redox couples. The article details state-of-the-art methodologies for constructing and applying these biosensors in live cells and animal models, including targeted subcellular localization and real-time imaging protocols. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to mitigate common pitfalls like pH interference and photobleaching. Finally, it offers a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of sensor performance, empowering scientists to select and implement the optimal tools for deciphering redox signaling in physiology and disease.

The Molecular Blueprint: Understanding Redox Probe Design and Sensing Mechanisms

Genetically encoded redox probes are sophisticated biosensors engineered from two core molecular components: a fluorescent protein (FP) scaffold that provides a detectable optical signal, and a redox-sensory domain that undergoes specific conformational or chemical changes in response to redox dynamics [1] [2]. These probes can be introduced into living cells and organisms via DNA transfection, enabling real-time, non-invasive monitoring of redox processes such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, glutathione redox potential shifts, and metabolic changes with high spatial and temporal resolution [1] [3]. This application note details the core principles, components, and experimental protocols for utilizing these powerful tools in redox biology research and drug development.

Core Component 1: The Fluorescent Protein Scaffold

The fluorescent protein scaffold forms the structural and functional backbone of genetically encoded redox probes, serving as both a stable platform for the sensory domain and the source of fluorescence readout.

Structural and Functional Properties

Fluorescent proteins share a conserved β-barrel structure consisting of 8 to 12 β-strands arranged in a cylindrical formation, with an internal α-helix containing the self-generated chromophore [4]. This robust scaffold shields the chromophore from the external environment, providing consistent fluorescence properties while allowing strategic engineering for sensor function. The chromophore originates from an internal tripeptide sequence (typically X65-Tyr66-Gly67 in Aequorea victoria GFP) that undergoes autocatalytic cyclization, dehydration, and oxidation to form a mature, fluorescent conjugate system [4]. Molecular oxygen is the only external cofactor required for chromophore maturation, making FPs particularly suitable for genetic encoding [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Fluorescent Protein Scaffolds Used in Redox Probe Development

| FP Scaffold | Chromophore Type | Excitation/Emission Peaks (nm) | Key Properties | Applications in Redox Probes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP (Redox-sensitive GFP) | GFP-like (p-hydroxybenzylideneimidazolidone) | ~400/475 (protonated) ~490/510 (deprotonated) | Excitation-ratiometric; reversible redox response; pH-sensitive | roGFP1, roGFP2, roGFP2-Orp1, roGFP2-Grx1 |

| rxYFP (Redox-sensitive YFP) | YFP variant | ~515/525 | Emission intensity-based; reversible redox response; highly pH-sensitive | rxYFP, rxYFP-Grx fusions |

| cpYFP (Circularly permuted YFP) | YFP variant | ~490/520 | Permuted topology enables fusion to sensory domains; conformation-sensitive | HyPer sensor family |

| sfGFP (Superfolder GFP) | GFP-like | ~485/510 | Enhanced folding efficiency; high stability; resistant to aggregation | Engineered scaffolds for peptide presentation |

Engineering Strategies for Sensor Development

Several protein engineering strategies have been successfully employed to convert fluorescent proteins into sensitive redox biosensors:

- Surface cysteine introduction: Strategic placement of cysteine residues on the β-barrel surface enables formation of reversible disulfide bonds that modulate chromophore fluorescence properties, as demonstrated in roGFP and rxYFP [1] [2].

- Circular permutation: Creating new N- and C-termini near the chromophore while linking the original termini enables direct coupling of conformational changes in fused sensory domains to fluorescence changes, as utilized in the HyPer sensor [1] [2].

- Fusion protein construction: Linking full FPs to redox-sensory proteins enables fluorescence readout of redox-dependent conformational changes through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) or other mechanisms [1].

- Scaffold presentation: The rigid FP β-barrel can serve as a presentation scaffold for structurally constrained peptides, maintaining their conformation while enabling fluorescent detection of target binding [5].

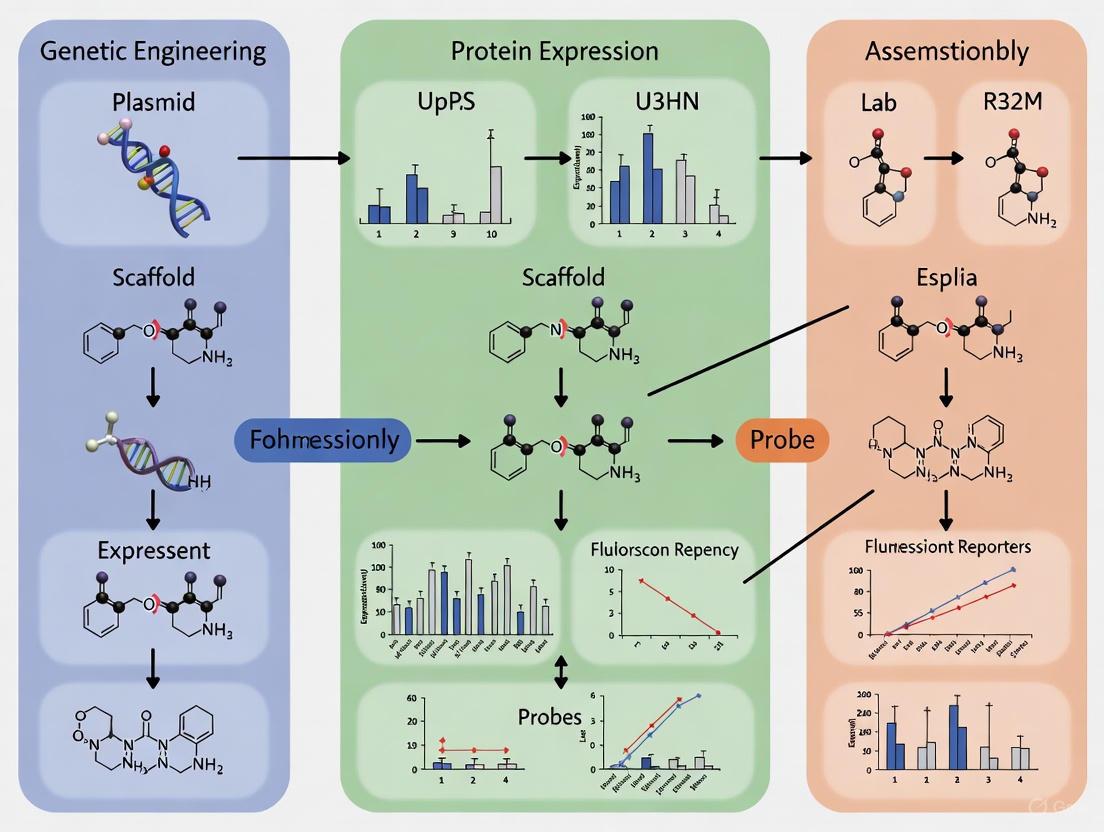

Diagram 1: Fluorescent protein scaffold engineering strategies for redox probe development.

Core Component 2: Redox-Sensory Domains

Redox-sensory domains provide the specificity and responsiveness to redox dynamics in genetically encoded probes, converting biochemical events into measurable conformational changes.

Classification and Mechanisms

Redox-sensory domains can be categorized based on their mechanism of action and target analytes:

- Thiol-disulfide switch domains: These domains contain cysteine residues that undergo reversible oxidation to form disulfide bonds, inducing conformational changes. Examples include glutaredoxin (Grx) and thioredoxin domains that equilibrate with the glutathione redox couple [1] [2].

- Peroxide-sensing domains: Specialized domains such as the bacterial OxyR regulatory domain and Orp1 peroxidase undergo conformational changes specifically in response to hydrogen peroxide and organic hydroperoxides [1].

- Heme-based sensory domains: GAF domains containing bound heme cofactors can function as redox sensors through ligand-switching mechanisms, as demonstrated in cyanobacterial proteins like All4978 [6].

- NAD(H)/NADP(H) binding domains: Domains such as those derived from Rex proteins reorient in response to the binding of reduced nicotinamide cofactors, enabling quantification of NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH ratios [3].

Table 2: Redox-Sensory Domains and Their Characteristics in Genetically Encoded Probes

| Sensory Domain | Redox Target | Mechanism of Action | Key Features | Example Probes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glutaredoxin (Grx) | Glutathione redox potential (GSH/GSSG) | Catalyzes disulfide exchange with FP scaffold; equilibrates with glutathione pool | Requires endogenous Grx for rapid response; reports glutathione redox potential | roGFP2-Grx1, rxYFP-Grx |

| Orp1/GPx3 | H₂O₂ | Peroxidase activity oxidizes domain, transferred to FP via disulfide exchange | Highly specific for H₂O₂; reversible in cellular environment | roGFP2-Orp1 |

| OxyR | H₂O₂ | Direct oxidation forms disulfide bond, inducing conformational change in cpFP | Specific for H₂O₂ over other ROS; moderate pH sensitivity | HyPer family |

| GAF domain (heme-binding) | Redox potential | Ligand switching (Cys/His) in heme coordination sphere based on oxidation state | Very low midpoint potential (-445 mV); novel signaling mechanism | All4978-based sensors |

| Rex domain | NAD+/NADH ratio | Conformational change upon NADH binding | Reports NADH/NAD+ ratio; specific for NADH over NADPH | Peredox, RexYFP |

Redox Signaling and Specificity Mechanisms

The molecular mechanisms underlying redox sensing involve precise chemical interactions that confer specificity:

- Thiol-disulfide chemistry: Sensory cysteines exist as thiolate anions at physiological pH, making them highly susceptible to oxidation. The resulting disulfide bonds alter protein conformation until reduced by cellular antioxidant systems [1] [2].

- Peroxide sensing specificity: OxyR and Orp1 domains achieve H₂O₂ specificity through reaction kinetics—they react rapidly with H₂O₂ but slowly with other oxidants. The OxyR domain in HyPer forms a reversible disulfide bond upon H₂O₂ exposure, inducing conformational changes in the fused cpYFP [1].

- Ligand switching in heme sensors: The GAF domain in All4973 undergoes a unique Cys-His ligand switch between ferric and ferrous states, with cysteine coordination in the Fe³⁺ state and histidine coordination in the Fe²⁺ state, enabling redox-dependent signaling [6].

- Cofactor binding: NADH-binding domains such as Rex undergo conformational changes when reduced cofactors bind, altering the chromophore environment of fused FPs and modulating fluorescence output [3].

Integrated Redox Probe Systems

The combination of optimized FP scaffolds with specific redox-sensory domains has produced a diverse toolkit for monitoring redox dynamics in living systems.

Major Classes of Genetically Encoded Redox Probes

Table 3: Comprehensive Overview of Genetically Encoded Redox Probes

| Probe Name | FP Scaffold | Sensory Domain | Target Analyte | Response Mechanism | Dynamic Range | Excitation/Emission (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP1/2 | GFP | Engineered cysteines | Glutathione redox potential | Excitation ratio change (405/488 nm) via disulfide formation | ~5-10 fold ratio change | ~400,490/510 |

| HyPer | cpYFP | OxyR | H₂O₂ | Emission ratio change (420/500 nm) upon conformation change | ~2-5 fold ratio change | ~420,500/516 |

| roGFP2-Orp1 | roGFP2 | Orp1 peroxidase | H₂O₂ | Excitation ratio change via disulfide relay | ~5-8 fold ratio change | ~400,490/510 |

| roGFP2-Grx1 | roGFP2 | Grx1 | Glutathione redox potential | Excitation ratio change via glutathionylation | ~3-6 fold ratio change | ~400,490/510 |

| rxYFP | YFP | Engineered cysteines | Glutathione redox potential | Intensity change via disulfide formation | ~2-3 fold intensity change | ~514/527 |

| Peredox | cpFP | T-Rex | NADH/NAD+ ratio | FRET change upon NADH binding | ~2.5 fold ratio change | ~430,500/530,610 |

Redox Signaling Pathways and Probe Integration

Diagram 2: Integration of redox probes into cellular signaling pathways.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Characterization of Redox Probe Specificity and Response

Purpose: To validate the specificity and dynamic response of a genetically encoded redox probe to its intended target analyte.

Materials:

- Purified probe protein or transfected cells expressing the probe

- Appropriate reduction/oxidation buffers (e.g., DTT, H₂O₂, diamide)

- Fluorescence spectrophotometer or fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets

- Cuvettes or imaging chambers

- Target analytes and potential interferents

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- For purified proteins: Dialyze against appropriate buffer to remove contaminants.

- For cells: Culture transfected cells to appropriate confluency in imaging-compatible dishes.

Baseline Measurement:

- Acquire fluorescence spectra or images at both excitation wavelengths (e.g., 400 nm and 490 nm for roGFP probes).

- Calculate baseline ratio (F₄₀₀/F₄₉₀) for multiple samples (n ≥ 3).

Specificity Testing:

- Apply specific oxidant (e.g., 100-500 μM H₂O₂ for HyPer) to test group.

- Apply non-target oxidants (e.g., 1-2 mM diamide, SIN-1 for peroxynitrite) to control groups.

- Monitor fluorescence changes over 5-30 minutes.

Reversibility Assessment:

- After oxidation, apply specific reductant (e.g., 5-10 mM DTT) to test reversibility.

- Monitor fluorescence recovery over 10-60 minutes.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate normalized ratio changes (ΔR/R₀) for each condition.

- Determine statistical significance using appropriate tests (e.g., Student's t-test).

- Generate dose-response curves for target analytes to determine EC₅₀ values.

Troubleshooting:

- If response is weak: Verify protein expression/folding; optimize analyte concentration.

- If reversibility is incomplete: Extend reduction time or try alternative reductants.

- If pH sensitivity interferes: Include pH controls or use pH-insensitive variants.

Protocol 2: Live-Cell Imaging of Redox Dynamics

Purpose: To monitor real-time redox changes in living cells using genetically encoded probes.

Materials:

- Cells expressing redox probe (stable or transient transfection)

- Live-cell imaging chamber with environmental control (temperature, CO₂)

- Inverted fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets and camera

- Time-lapse imaging software

- Treatment agents of interest (drugs, stressors, etc.)

- Control compounds (specific oxidants, reductants)

Procedure:

- Microscope Setup:

- Configure excitation sources and emission filters for ratiometric imaging.

- Set environmental control to maintain 37°C and 5% CO₂.

- Calibrate imaging parameters to avoid saturation and minimize photobleaching.

Cell Preparation:

- Plate cells expressing probe in imaging-compatible dishes 24-48 hours before experiment.

- Replace medium with fresh, phenol-free imaging medium before experiment.

Image Acquisition:

- Acquire baseline images at both excitation wavelengths for 5-10 minutes.

- Apply treatment of interest without disturbing imaging field.

- Continue time-lapse acquisition with appropriate interval (e.g., 30-60 seconds).

- Include positive controls (e.g., bolus H₂O₂) at experiment end.

Data Processing:

- Perform background subtraction for all images.

- Calculate ratio images (F₁/F₂) for each time point.

- Define regions of interest (ROIs) for individual cells or compartments.

- Export ratio values over time for statistical analysis.

Data Interpretation:

- Normalize data to baseline (ΔR/R₀) for comparison across experiments.

- Determine significance of treatment effects compared to controls.

- Correlate redox changes with other cellular parameters if multiplexed.

Critical Considerations:

- Include controls for photobleaching, autofluorescence, and pH effects.

- Verify proper subcellular localization of probe using targeted variants.

- Use appropriate statistical methods for time-series data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Redox Probe Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pLVX, pcDNA3.1, pEGFP backbone | Probe delivery and expression | Choose promoter strength matching application; include selection markers |

| Targeting Sequences | MLS (mitochondria), NLS (nucleus), ER retention | Subcellular localization | Verify localization with marker dyes; optimize linker length |

| Oxidation Standards | H₂O₂, diamide, menadione | Positive controls for oxidation | Use fresh stocks; calibrate concentrations; include kinetics controls |

| Reduction Standards | DTT, TCEP, N-acetylcysteine | Positive controls for reduction | Prepare fresh solutions; consider membrane permeability |

| Validation Reagents | BSO (buthionine sulfoximine), auranofin | Perturb glutathione and thioredoxin systems | Verify efficacy in specific cell types; optimize concentration and timing |

| Microscopy Tools | Ratiometric filter sets, environmental chambers | Live-cell imaging | Match filter specifications to probe spectra; maintain physiological conditions |

The strategic combination of fluorescent protein scaffolds with specific redox-sensory domains has generated a powerful toolkit for monitoring redox dynamics in living systems. Understanding the core components—the structural and spectral properties of FP scaffolds coupled with the specificity and mechanism of redox-sensory domains—enables researchers to select appropriate probes for their specific applications and correctly interpret the resulting data. The continued development of red-shifted variants, improved specificity, and expanded target analytes will further enhance our ability to visualize and quantify redox biology in health and disease.

Chromophore Formation and the Role of Molecular Oxygen

In the fabrication and application of genetically encoded redox probes, understanding chromophore formation is not merely a biochemical curiosity—it is a fundamental prerequisite for designing sensors with high sensitivity, speed, and reliability. The chromophore, the light-emitting heart of any fluorescent protein (FP), is formed through a precise post-translational self-modification of a specific tripeptide sequence within the FP's β-barrel structure [7]. This process, however, is not autonomous. A critical external reactant is molecular oxygen (O₂), which serves as the final electron acceptor in the rate-limiting oxidation step that concludes chromophore maturation [8] [7]. The absolute dependence on O₂ creates an intrinsic link between the fluorescence of many FPs and the cellular redox environment, a link that is expertly exploited in the design of genetically encoded sensors for oxidants like hydrogen peroxide and for general redox potential [9] [1] [10]. Consequently, the kinetics and efficiency of chromophore formation directly impact the performance of these essential research tools, influencing experimental timelines, detection sensitivity, and the accurate reporting of dynamic redox processes in live cells and organisms [8] [11]. This application note details the role of O₂ and provides protocols for optimizing chromophore maturation in redox probe development.

The Dual Role of Oxygen in Fluorescent Protein Function

Molecular oxygen is indispensable for FP biogenesis and function, playing two distinct but crucial roles.

Oxygen in Chromophore Maturation

The maturation of the chromophore is an autocatalytic process that proceeds through several steps. A key final step is the oxidation of the chromophore precursor. In this dehydrogenation reaction, O₂ acts as the terminal electron acceptor, leading to the formation of a conjugated π-system responsible for fluorescence [8] [7]. The general pathway for a green FP chromophore involves:

- Cyclization: Formation of a five-membered heterocyclic ring from the tripeptide residues (typically Ser65, Tyr66, and Gly67 in A. victoria GFP).

- Dehydration: Loss of a water molecule from the cyclized intermediate.

- Oxidation: Introduction of a double bond into the heterocyclic ring via a dehydrogenation reaction that requires O₂ [7].

The kinetics of this maturation process are highly temperature-dependent. Research in cell-free expression systems has demonstrated that the maturation rate for common FPs like EGFP, EYFP, and mCherry increases significantly from room temperature to 37°C [8]. This has direct implications for experiment design, indicating that probes expressed in mammalian systems will mature faster than those in systems at lower temperatures.

Oxygen as a Quencher in Sensing Mechanisms

Beyond its role in maturation, O₂ is a potent dynamic quencher of phosphorescence due to its triplet ground state. This physical property is the fundamental operating principle for a distinct class of O₂ sensors, such as the single-chromophore, dual-emission Pt(II) complex PtQTAC [12]. In these sensors, an O₂-sensitive phosphorescent emission (red) is paired with an O₂-insensitive fluorescent reference signal (green). The phosphorescence intensity is quenched upon collision with O₂ molecules, following the Stern-Volmer relationship (I₀/I = 1 + Kₛᵥ[O₂]) [12]. The ratio of the two emissions provides a quantifiable, self-referenced measure of intracellular O₂ concentration, independent of probe concentration [12].

Table 1: Key Fluorescent and Phosphorescent Probes and Their Relationship with Oxygen

| Probe Name | Probe Type | Primary Role of O₂ | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFP, roGFP, HyPer | Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Protein | Chromophore Maturation (Reactant) | Redox and ROS sensing [9] [1] |

| PtQTAC | Synthetic Phosphorescent Complex | Signal Modulation (Quencher) | Quantitative intracellular O₂ mapping [12] |

| HyPerRed | Genetically Encoded Red Fluorescent Protein | Chromophore Maturation (Reactant) | H₂O₂ sensing in multicomponent assays [10] |

Quantitative Kinetics of Chromophore Maturation

The maturation half-time is a critical parameter for experimental planning, especially in time-sensitive studies. The kinetics are not uniform across different FPs and are strongly influenced by temperature.

Table 2: Maturation Kinetics of Common Fluorescent Proteins at Different Temperatures

| Fluorescent Protein | Maturation Half-Time at ~25°C (hours) | Maturation Half-Time at 37°C (hours) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFP | ~4 - 9 (extrapolated) | ~1 | Fast maturation at 37°C, suitable for kinetic studies [8]. |

| mCherry | ~4 - 9 (extrapolated) | ~1 | Matures efficiently at physiological temperatures [8]. |

| mTagBFP | Not Reported | 0.22 | Exceptionally fast maturation, ideal for rapid reporting [7]. |

| mKate2 | Not Reported | <0.33 | Fast-maturing red FP, useful for deep-tissue imaging [7]. |

| mOrange2 | Not Reported | 4.5 | Relatively slow maturation; requires careful experimental timing [7]. |

The data indicate that FPs can be selected based on maturation speed to suit specific experimental needs. For instance, mTagBFP is an excellent choice when a rapid signal is required, whereas the slower maturation of mOrange2 must be accounted for in the experimental timeline.

Workflow: Chromophore Maturation and Its Application in Redox Sensing

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of chromophore maturation and how it is leveraged in redox biology tools, connecting the roles of O₂, the maturation process, and final sensor function.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Monitoring Chromophore Maturation Kinetics in a Cell-Free System

This protocol, adapted from studies using fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy, allows for quantitative analysis of maturation kinetics under controlled conditions [8].

Key Materials:

- S30 T7 High-Yield Protein Expression System (Promega) or equivalent cell-free expression system.

- Plasmid DNA encoding the FP or FP-fusion protein of interest.

- Nuclease-free water.

- RNase A (e.g., Sigma-Aldrich).

- Eight-well coverglass chamber slides.

- Vacuum grease.

- Fluorescence spectrometer or confocal microscope with temperature control.

Methodology:

- Cell-Free Reaction Setup: Prepare the cell-free protein expression reaction according to the manufacturer's instructions, adding the plasmid DNA encoding your FP.

- Expression: Incubate the reaction mixture at the desired temperature (e.g., 25°C, 30°C, or 37°C) for 2-4 hours to allow for protein synthesis. The chromophore will not mature fully during this time.

- Reaction Termination: Stop the synthesis reaction by adding 0.1% RNase A to degrade RNA and halt translation.

- Clarification: Centrifuge the reaction at 18,000 × g for 20 minutes to remove large particles that could interfere with fluorescence measurements.

- Sample Loading: Transfer the supernatant to a ring of vacuum grease created within a well of an eight-well coverglass chamber to prevent evaporation.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately place the chamber on a fluorescence spectrometer or microscope. Continuously monitor the fluorescence intensity (e.g., Ex: 488 nm / Em: 510 nm for EGFP) over several hours at a constant temperature.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting fluorescence time course to a first-order exponential function:

F(t) = F₀ + ΔF(1 - e^(-t/τ)), whereτis the maturation time constant. The half-time is calculated ast₁/₂ = τ * ln(2)[8].

Protocol 2: Chromophore Pre-maturation for Split-FP Assays

This protocol describes a method to pre-mature the GFP1-10 fragment, significantly accelerating signal generation in split-GFP-based protein secretion assays [11]. This principle can be applied to other split-FP systems to improve speed and sensitivity for redox signaling studies.

Key Materials:

- Purified GFP 1-10 protein (from inclusion bodies).

- His₆-Z_GFP 11 protein (soluble, purified via IMAC).

- NHS-activated Sepharose beads.

- Coupling buffer: 0.2 M NaHCO₃, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3.

- Elution buffer: 0.1 M Glycine-HCl, pH 2.5.

- Neutralization buffer: 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

Methodology:

- Immobilize GFP 11: Covalently couple the purified His₆-ZGFP 11 protein to NHS-activated Sepharose beads according to the manufacturer's protocol. Use approximately 2.5 ml of 0.87 mM His₆-ZGFP 11 for 5 ml of bead slurry.

- Pre-maturation Incubation: Incubate the GFP 1-10 protein (e.g., 40 ml of 50 µM) with the His₆-Z_GFP 11 beads overnight at room temperature with gentle agitation. During this step, GFP 1-10 binds to the immobilized GFP 11 and its chromophore matures, turning the bead slurry green.

- Washing: Wash the beads extensively to remove non-specifically bound GFP 1-10.

- Elution: Elute the pre-maturated GFP 1-10 (GFP 1-10mat) from the beads using low-pH elution buffer.

- Neutralization and Refolding: Immediately neutralize the eluate with Tris-HCl buffer and refold the protein if necessary. The resulting GFP 1-10mat is ready for use.

- Validation: Confirm maturation via mass spectrometry (observing a ~21 Da mass shift) [11]. Using GFP 1-10mat can lead to a >150-fold faster initial signal generation compared to non-maturated protein in complementation assays [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Chromophore and Redox Probe Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Protein Expression System | In vitro transcription/translation system. | Studying chromophore maturation kinetics without cellular complexity [8]. |

| roGFP (Redox-Sensitive GFP) | Genetically encoded indicator for glutathione redox potential (E_GSH). | Ratiometric measurement of subcellular redox states [9] [1] [13]. |

| HyPer Family Sensors | Genetically encoded, highly specific H₂O₂ sensors. | Detecting localized H₂O₂ production in signaling, e.g., upon growth factor stimulation [1] [10]. |

| HyPerRed | First genetically encoded red fluorescent H₂O₂ sensor. | Multiparametric imaging with other green fluorophores [10]. |

| PtQTAC Complex | Single-chromophore, dual-emission O₂ sensor. | Quantitative intracellular O₂ mapping via phosphorescence quenching [12]. |

| Split-FP Fragments (GFP 1-10/11) | Non-fluorescent FP fragments for complementation assays. | Detecting protein-protein interactions or protein secretion; pre-maturation boosts speed [11]. |

Redox processes are involved in almost every cell of the body as a consequence of aerobic life, serving as conserved regulators of numerous cellular functions [1]. Over the past decades, redox biology has been increasingly recognized as a key theme in cell signaling, facilitated by the development of fluorescent probes that can monitor redox conditions and dynamics in cells and cell compartments with subcellular resolution [1]. Genetically encoded redox probes represent a revolutionary technology that allows researchers to monitor redox dynamics in living systems in real-time. These probes are introduced into cells or organisms as DNA and expressed into functional proteins by intracellular machinery, enabling them to be precisely targeted to specific subcellular compartments through localization sequences or to the vicinity of proteins of interest via genetic fusions [1]. This versatility has transformed our ability to investigate biochemical dynamics with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution, moving beyond the limitations of traditional colorimetric, electrochemical, and chromatographic assays that often require sample processing and provide limited spatial and temporal information [1].

The fundamental advantage of genetically encoded probes lies in their self-catalyzed chromophore formation, which requires no external cofactors or enzymatic activities beyond molecular oxygen [2]. This unique property enables researchers to introduce FP-encoding genes into model organisms, resulting in expression of functional fluorescent proteins detectable by fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, and other fluorescence-based methods [2]. As these probes have evolved, they have been engineered for increased specificity, dynamic range, and compatibility with multiparametric imaging, making them indispensable tools for modern redox biology research in fields ranging from basic cell biology to drug development.

Major Classes of Redox Probes

roGFP (Redox-Sensitive Green Fluorescent Protein)

roGFP represents a cornerstone technology in genetically encoded redox sensing. Developed through the strategic introduction of surface-exposed cysteine residues into the β-barrel structure of green fluorescent protein, roGFP functions through the reversible formation of disulfide bonds in response to oxidative changes in the cellular environment [1] [2]. These engineered cysteine residues are positioned in the vicinity of the chromophore, such that disulfide bond formation alters the fluorescence properties of the protein, creating a sensitive readout of redox conditions.

Mechanism of Action: The roGFP probes are excitation-ratiometric, exhibiting shifts in their excitation spectrum when oxidized versus reduced, while the emission spectrum remains largely unchanged [1]. This ratiometric property makes them less sensitive to variations in probe expression levels and fluorescence photobleaching, enabling more reliable quantitative measurements [1]. Importantly, roGFPs do not directly react with reactive oxygen species (ROS) under physiological conditions due to the relatively low reaction rate of their cysteine residues with H₂O₂ [2]. Instead, they equilibrate with the cellular glutathione redox couple through glutaredoxin (Grx)-catalyzed mechanisms [1]. The availability of Grx thus becomes a rate-limiting factor in the thiol-disulfide exchange process, making roGFPs effectively sensors for the glutathione redox potential (GSH/GSSG ratio) in cellular compartments where Grx is present [1] [2].

Spectral Properties and Variants: roGFP typically displays excitation maxima at approximately 400 nm and 490 nm, with emission around 510 nm [2]. The ratio of fluorescence excited at 400 nm versus 490 nm provides a quantitative measure of the oxidation state, with higher ratios indicating more oxidized conditions. Researchers have developed variants of roGFP with different redox potentials, making them particularly valuable for imaging redox dynamics in cell compartments with different basal redox levels [1]. A significant advancement came with the creation of roGFP2-Orp1, where roGFP2 was fused to the yeast peroxidase Orp1, creating a probe that directly responds to H₂O₂ through a redox relay mechanism [2].

rxYFP (Redox-Sensitive Yellow Fluorescent Protein)

rxYFP operates on a similar principle to roGFP but utilizes yellow fluorescent protein as its structural scaffold. Like roGFP, rxYFP contains engineered surface-exposed cysteine residues that can form reversible disulfide bonds in response to changes in the cellular redox environment [1] [2]. The formation and reduction of these disulfide bonds directly affect the chromophore environment, leading to measurable changes in fluorescence properties.

Mechanism of Action: The redox sensitivity of rxYFP stems from the proximity of the engineered cysteine residues to the chromophore. When these residues form a disulfide bond, the structural alteration affects the chromophore's ionization equilibrium, shifting between a neutral and an anionic state [1]. This shift manifests as a change in fluorescence intensity that can be monitored to assess redox conditions. Similar to roGFP, rxYFP equilibrates with the glutathione redox couple primarily through glutaredoxin-catalyzed reactions rather than through direct interaction with ROS [1]. The kinetics of this equilibration depend on the availability and activity of glutaredoxin in the specific cellular compartment where rxYFP is expressed.

Applications and Limitations: rxYFP has been successfully used to monitor redox changes in various cellular compartments and model systems. However, a significant consideration when using rxYFP is its sensitivity to pH changes, as the chromophore equilibrium between neutral and anionic states is influenced by both redox state and pH [2]. This pH sensitivity necessitates careful controls to distinguish genuine redox changes from pH artifacts in experimental settings. Additionally, unlike the ratiometric nature of roGFP, rxYFP measurements typically rely on intensity changes, making them potentially more susceptible to artifacts from variations in probe concentration or optical path length.

HyPer Family Sensors

The HyPer family represents a distinct class of genetically encoded probes specifically designed for detecting hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). Unlike roGFP and rxYFP, which primarily report on the glutathione redox state, HyPer probes directly and selectively respond to H₂O₂ dynamics, making them invaluable tools for studying redox signaling processes [2] [10].

Molecular Design: HyPer was created by fusing a circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) with the regulatory domain of the bacterial H₂O₂-sensing protein OxyR (OxyR-RD) [2] [10]. The OxyR regulatory domain contains a critical cysteine residue (Cys199) that has a low pKa and resides in a hydrophobic pocket [10]. These features confer exceptional selectivity toward H₂O₂, as the hydrophobic pocket prevents access to charged oxidants such as superoxide [10]. When H₂O₂ oxidizes Cys199, the resulting sulfenic acid form quickly forms a disulfide bond with a nearby cysteine residue (Cys208), inducing a conformational change in the OxyR domain that is transduced to the cpYFP, altering its fluorescence properties [10].

Spectral Properties and Selectivity: HyPer is an excitation-ratiometric probe, with oxidation causing a decrease in fluorescence when excited at 500 nm and an increase when excited at 420 nm [2]. This ratiometric response enables quantitative measurements that are largely independent of probe concentration. HyPer demonstrates high specificity for H₂O₂ over other oxidants, showing minimal response to superoxide, nitric oxide, oxidized glutathione, or peroxynitrite [10]. The probe is reversible in cells, with cellular reducing systems such as thioredoxin and potentially the glutaredoxin/GSH system reducing the disulfide bond and returning the probe to its reduced state [1].

Advanced Variants: The original HyPer probe has been succeeded by improved versions, including HyPer-2 and HyPer-3, which offer expanded dynamic range and faster redox kinetics [1]. More recently, a red fluorescent variant called HyPerRed was developed by replacing the cpYFP portion with a circularly permuted red fluorescent protein (cpRed) from the R-GECO1 calcium sensor [10]. HyPerRed exhibits excitation and emission maxima at 575 nm and 605 nm, respectively, providing the same sensitivity and selectivity as its green counterparts while enabling multiparametric imaging with other green-emitting probes [10].

NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH Sensors

Beyond thiol redox state and ROS sensing, significant efforts have been dedicated to developing genetically encoded probes for monitoring the redox states of pyridine nucleotides, particularly the NAD⁺/NADH and NADP⁺/NADPH couples. These nucleotide pairs are central to metabolic pathways and redox homeostasis, making them critical targets for monitoring cellular metabolic states.

Peredox and Related NAD⁺/NADH Sensors: Peredox-mCherry was developed as an NAD redox state sensor that incorporates a circularly permuted T-Sapphire (TS) fluorescent protein nested between two copies of the NADH/NAD⁺-binding domain of the bacterial transcriptional repressor Rex [14] [2]. Structural changes in the Rex domains, depending on whether they bind NAD⁺ or NADH, induce fluorescence changes in the TS module that can be normalized against the signal from a C-terminally fused mCherry fluorescent protein [14]. Peredox offers several advantages, including limited pH sensitivity and high apparent brightness in biological systems compared to some cpYFP-based sensors [14].

NAPstars Family of NADP Redox State Sensors: More recently, the NAPstars family was introduced as a suite of genetically encoded biosensors specifically designed to monitor the NADPH/NADP⁺ redox couple [14]. These sensors were developed by mutating the binding pocket of Peredox to favor NADP binding over NAD binding, creating probes that can monitor NADP redox states across a remarkable 5000-fold range, spanning NADPH/NADP⁺ ratios from approximately 0.001 to 5 [14]. The NAPstars demonstrate pronounced NADPH-dependent changes in fluorescence excitation and emission spectra, with excitation and emission maxima at approximately 400 nm and 515 nm, respectively, and a spectroscopic dynamic range similar to Peredox [14]. Importantly, NAPstars respond to the genuine NADPH/NADP⁺ ratio rather than solely to the NADPH concentration, making them true reporters of NADP redox state [14].

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Major Genetically Encoded Redox Probes

| Probe Class | Primary Target | Sensing Mechanism | Spectral Properties | Dynamic Range | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP | GSH/GSSG ratio | Glutaredoxin-coupled disulfide formation | Excitation ratiometric (400/490 nm, emission ~510 nm) | Varies by variant | Ratiometric, subcellular targetable, multiple variants with different redox potentials | Indirect H₂O₂ sensing via glutathione system, pH-sensitive chromophore |

| rxYFP | GSH/GSSG ratio | Glutaredoxin-coupled disulfide formation | Intensity-based | Not specified in sources | Compatible with other GFP-based probes | pH-sensitive, intensity-based measurements more prone to artifacts |

| HyPer | H₂O₂ | Direct oxidation of OxyR domain | Excitation ratiometric (420/500 nm) | Responds to 10-400 μM H₂O₂ in cells | Direct, specific H₂O₂ detection, ratiometric | pH-sensitive below 7.0, can be photobleached with blue light |

| HyPerRed | H₂O₂ | Direct oxidation of OxyR domain | Excitation at 575 nm, emission at 605 nm | Responds to 10-400 μM H₂O₂ in cells | Red spectrum enables multiplexing, bright (ε×QY=11,300) | Higher pKa (8.5-8.7) limits use in alkaline conditions |

| Peredox | NAD⁺/NADH | Rex domain conformational changes | TS excitation ~400 nm/emission ~515 nm, mCherry reference | Kd(NADH) = 1.2 μM | Limited pH sensitivity, internal reference (mCherry) | Primarily responds to NAD⁺/NADH ratio |

| NAPstars | NADPH/NADP⁺ | Engineered Rex domain conformational changes | Excitation ~400 nm, emission ~515 nm | NADPH/NADP⁺ ratios 0.001-5 | Broad dynamic range, specific for NADP couple | Newer probes with ongoing characterization |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Considerations for Using Genetically Encoded Redox Probes

Before implementing any specific protocol, researchers must consider several fundamental aspects of working with genetically encoded redox probes. First, careful selection of the appropriate probe for the biological question is essential. Investigators must determine whether they aim to monitor general thiol redox state (roGFP, rxYFP), specific ROS such as H₂O₂ (HyPer, roGFP2-Orp1), or pyridine nucleotide ratios (Peredox, NAPstars) [2]. Second, the choice of expression system must align with experimental goals, considering whether transient transfection, stable expression, or viral transduction best suits the model system. For primary human coronary artery endothelial cells, for example, adenovirus-based transduction has proven effective for introducing mito-roGFP [15]. Third, proper controls are imperative, including pH controls for pH-sensitive probes, expression-level controls, and verification of subcellular localization.

Protocol: Measuring Mitochondrial Redox Status with Mito-roGFP

The following optimized protocol for measuring mitochondrial oxidative status in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC) can be adapted for other cell types with appropriate modifications [15]:

Step 1: Probe Expression

- Transduce cells with mito-roGFP adenovirus at an appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI) in complete cell culture medium. For HCAEC, incubation for 24 hours typically provides sufficient expression.

- Include control cells transduced with empty vector or expressing non-responsive probe variants.

Step 2: Live-Cell Imaging Preparation

- Plate transduced cells on appropriate imaging chambers or dishes to reach 60-80% confluency at time of imaging.

- Before imaging, replace culture medium with fresh pre-warmed imaging buffer compatible with live cells (e.g., Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution).

Step 3: Calibration and Measurement

- Acquire baseline ratiometric images using appropriate filter sets for roGFP (excitation at 400 nm and 490 nm, emission at 510 nm).

- Treat cells with 2 mM final concentration of the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) to fully reduce the probe, and acquire images after 5-10 minutes.

- Wash cells and treat with 100 μM final concentration of the oxidizing agent diamide to fully oxidize the probe, acquiring images after 5-10 minutes.

- Include experimental treatments between baseline and calibration measurements as required by the experimental design.

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Calculate the 400/490 nm excitation ratio for each condition after background subtraction.

- Determine the degree of oxidation using the formula: Oxidation degree = (R - Rmin) / (Rmax - R), where R is the measured ratio, Rmin is the ratio under fully reducing conditions, and Rmax is the ratio under fully oxidizing conditions.

- Normalize data across multiple experiments to account for variations in expression levels.

Protocol: Application of HyPerRed for Cytoplasmic H₂O₂ Detection

The following protocol outlines the use of HyPerRed for detecting cytoplasmic H₂O₂ production in response to growth factor stimulation [10]:

Step 1: Cell Preparation and Transfection

- Culture cells (e.g., HeLa Kyoto) in appropriate medium under standard conditions.

- Transfect with HyPerRed plasmid using standard transfection methods suitable for the cell type.

- Allow 24-48 hours for expression before imaging.

Step 2: Live-Cell Imaging

- Use fluorescence microscopy with excitation at 575 nm and emission collection at 605 nm.

- Acquire baseline images of cells in standard imaging buffer.

- Stimulate cells with growth factors (e.g., 100 ng/mL EGF) and continue time-lapse imaging to capture dynamic changes.

- Maintain cells at 37°C with appropriate environmental control throughout imaging.

Step 3: Specificity Controls

- Treat separate samples with the H₂O₂-scavenging enzyme catalase (1000 U/mL) prior to growth factor stimulation to confirm the specificity of the response.

- Use HyPerRed-C199S, a non-responsive mutant, as a negative control to verify that observed changes are specific to H₂O₂ sensing.

Step 4: Data Quantification

- Quantify fluorescence intensity changes over time, normalizing to baseline values.

- Express results as ΔF/F, where F is baseline fluorescence and ΔF is the change in fluorescence.

- Compare kinetics and magnitude of responses across experimental conditions.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

roGFP Redox Sensing Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanism through which roGFP senses the cellular glutathione redox state:

Diagram 1: roGFP functions as a glutathione redox potential sensor through glutaredoxin-catalyzed disulfide exchange. Oxidative stress converts reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), which then transfers disulfides to roGFP via glutaredoxin, causing conformational changes that alter fluorescence excitation properties [1] [2].

HyPer H₂O₂ Sensing Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the specific molecular mechanism by which HyPer detects hydrogen peroxide:

Diagram 2: HyPer directly detects H₂O₂ through oxidation of specific cysteine residues in the OxyR regulatory domain, leading to disulfide bond formation, conformational changes, and altered fluorescence of the circularly permuted fluorescent protein. The process is reversible through cellular reducing systems [2] [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Redox Probe Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | roGFP1/2 plasmids, HyPer plasmids, NAPstars constructs | Probe delivery and expression | Select promoters appropriate for your cell type; consider inducible systems for toxic probes |

| Validation Reagents | Dithiothreitol (DTT), Diamide, H₂O₂ | Probe calibration and functionality testing | Use fresh preparations; concentration optimization required for different cell types |

| Compromised Function Controls | roGFP-Cys-mutants, HyPer-C199S, NAPstarC | Specificity controls | Express alongside wild-type probes to distinguish specific from nonspecific responses |

| Compartmentalization Markers | Mito-DsRed, ER-GFP, Nuclear markers | Subcellular localization verification | Co-transfect or use stable lines to confirm proper targeting of redox probes |

| Redox System Modulators | Buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), Auranofin, Menadione | Manipulation of cellular redox state | Use to perturb specific pathways (GSH synthesis, thioredoxin reductase, etc.) |

| Environmental Controls | Nigericin, Monensin, CO₂-independent medium | pH control and calibration | Essential for pH-sensitive probes; use ionophores with high-K⁺ buffers for pH clamping |

| Detection Reagents | Appropriate primary/secondary antibodies | Immunodetection and validation | Useful for confirming expression levels when fluorescence is insufficient |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of genetically encoded redox probes has yielded significant insights across diverse biological systems. The NAPstars family of NADP redox state biosensors, for instance, has revealed in vivo dynamics of central redox metabolism across eukaryotes, demonstrating a conserved robustness of cytosolic NADP redox homeostasis and uncovering cell cycle-linked NADP redox oscillations in yeast [14]. Similarly, HyPer and its derivatives have enabled real-time monitoring of H₂O₂ production in response to diverse stimuli, from growth factor stimulation in mammalian cells to environmental challenges in plants [2] [10].

Future developments in genetically encoded redox probes are likely to focus on several key areas. First, expanding the color palette toward red and far-red wavelengths remains a priority, as this would enable multiplexing with other probes and reduce autofluorescence in deep-tissue imaging [2]. The recent development of HyPerRed represents a significant step in this direction [10]. Second, improving specificity and dynamic range while reducing pH sensitivity will enhance data quality and interpretation. Third, developing probes for additional redox-active molecules, such as nitric oxide (NO), superoxide (O₂•⁻), and hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), would provide a more comprehensive toolkit for interrogating redox biology [1] [2]. Finally, creating transgenic organisms expressing these probes will facilitate the study of redox processes in intact physiological systems, bridging the gap between in vitro observations and in vivo functionality.

As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly uncover new dimensions of redox biology and provide unprecedented insights into the role of redox processes in health, disease, and therapeutic interventions. The integration of these probes with other advanced technologies, such as super-resolution microscopy, high-content screening, and in vivo imaging, will further expand their utility in basic research and drug development.

The precise measurement of redox dynamics in living systems is fundamental to advancing our understanding of cellular signaling, oxidative stress, and drug mechanisms. Genetically encoded redox probes have emerged as indispensable tools for these investigations, enabling real-time, subcellular resolution imaging of redox processes in living cells and organisms [16]. This application note details the core molecular sensing mechanisms—disulfide bond formation, glutaredoxin coupling, and conformational change—that underpin the function of these sophisticated biosensors. We provide experimental protocols and quantitative characterisation data to support researchers in the fabrication, implementation, and validation of these probes within drug discovery and basic research applications.

Core Sensing Mechanisms & Molecular Architectures

Mechanism 1: Disulfide Bond Formation

The reversible formation of disulfide bonds in response to oxidants is a primary sensing mechanism for many genetically encoded probes.

- Molecular Principle: This mechanism relies on the oxidation of specific, redox-active cysteine thiolates (Cys-S-) to form a disulfide bond (Cys-S-S-Cys). This reaction is highly specific for hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) when the cysteines are situated within a hydrophobic protein pocket, which excludes charged oxidants like the superoxide anion [17] [18].

- Probe Architecture: The HyPer family of probes exemplifies this design. HyPer was constructed by inserting a circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) into the regulatory domain of the E. coli H₂O₂-sensing protein OxyR (OxyR-RD) [17]. The oxidation of Cys199 and subsequent disulfide bond formation with Cys208 induces a conformational change in the OxyR-RD, which in turn alters the fluorescence properties of the cpYFP.

- Spectral Response: The formation of the disulfide bond causes a ratiometric change in the probe's excitation spectrum, which is a key feature for quantitative imaging, as it minimizes artifacts related to probe concentration or optical path length [17] [16].

The following diagram illustrates the H₂O₂ sensing pathway via disulfide bond formation in a typical probe like HyPer.

Mechanism 2: Glutaredoxin Coupling

For measuring the redox state of specific cellular couples, sensors utilize catalytic coupling with oxidoreductase enzymes.

- Molecular Principle: Probes like Grx1-roGFP2 do not directly react with glutathione. Instead, they are coupled to human glutaredoxin 1 (Grx1), which catalyzes the reversible electron exchange between the glutathione pool (GSH/GSSG) and the probe itself [16]. This design makes the probe highly specific and responsive to the glutathione redox potential (E_GSH).

- Probe Architecture: The sensor is a fusion protein where Grx1 is tethered to roGFP2, a redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein. roGFP2 contains two cysteine residues on its beta-barrel surface that can form a disulfide bond, modulating its fluorescence [16].

- Spectral Response: Similar to HyPer, the Grx1-roGFP2 probe exhibits a ratiometric shift in its excitation spectrum upon oxidation or reduction, allowing for quantitative measurement of E_GSH [16].

The workflow below details the catalytic mechanism by which Grx1-roGFP2 reports the glutathione redox potential.

Mechanism 3: Conformational Change

Beyond simple disulfide formation, larger-scale conformational changes can be harnessed for sensing and functional control.

- Molecular Principle: The oxidation of cysteine residues can trigger extensive structural rearrangements in a protein. A demonstrated example involves a disulfide-rich peptide that, upon oxidation, folds into an amphiphilic β-hairpin conformation [19]. This folding is driven by the formation of specific disulfide bonds and is stabilized by intermolecular interactions like tryptophan-tryptophan pairing.

- Functional Output: This oxidation-induced conformational change can lead to macroscopic phenomena, such as the self-assembly of the peptides into a mechanically rigid hydrogel. The process is reversible; applying a reducing agent breaks the disulfide bonds, unfolds the peptides, and dissolves the hydrogel [19].

- Application Scope: While this mechanism is not yet widely used in classical fluorescent biosensors, it represents a powerful approach for creating redox-responsive biomaterials for applications like drug delivery [19].

The diagram below illustrates the reversible peptide assembly controlled by redox state.

Quantitative Sensor Characterization Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for representative probes based on the described mechanisms.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Genetically Encoded Redox Probes

| Probe Name | Target Analyte | Sensing Mechanism | Dynamic Range (ΔF/F or Ratio Change) | Sensitivity / Kd | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HyPerRed | H₂O₂ | Disulfide Bond Formation | ~80% fluorescence increase | 20-300 nM (H₂O₂ in vitro) | [17] |

| Grx1-roGFP2 | Glutathione Redox Potential (E_GSH) | Glutaredoxin Coupling | Ratiometric, pH-independent | N/A (Reports E_GSH) | [16] |

| geNOp | Nitric Oxide (NO) | Metal Coordination & FP Quenching | 7-18% fluorescence quenching | 50-94 nM (NOC-7 donor) | [20] |

Table 2: Key Biophysical and Optical Properties of HyPerRed

| Property | Value | Experimental Condition | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Peak | 575 nm | In vitro, purified protein | [17] |

| Emission Peak | 605 nm | In vitro, purified protein | [17] |

| Brightness | 11,300 (ϵ × QY) | Ext. coeff. 39,000 M⁻¹cm⁻¹, QY 0.29 | [17] |

| pH Sensitivity (pKa) | 8.5 (oxidized), 8.7 (reduced) | In vitro titration | [17] |

| Response Time | Reversible in 8-10 min | In E. coli cytoplasm | [17] |

| Selectivity | High for H₂O₂ | No response to NO, O₂•⁻, ONOO⁻, GSSG | [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In Vitro Characterization of a Novel H₂O₂ Probe

This protocol is adapted from the characterization of HyPerRed and is essential for determining the basic spectroscopic and kinetic properties of a new disulfide bond-based sensor [17].

1. Protein Purification:

- Cloning & Expression: Clone the gene for the probe into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET series for bacterial expression). Transform into a suitable E. coli strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Induction & Lysis: Induce expression with IPTG. Harvest cells by centrifugation and lyse using sonication or a homogenizer in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Include 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) in the lysis buffer to maintain cysteines in a reduced state.

- Purification: Purify the protein using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) if it carries a polyhistidine tag. Elute with an imidazole gradient.

- Buffer Exchange: Remove imidazole and 2-ME by passing the eluted protein through a desalting column (e.g., PD-10) equilibrated with a clean assay buffer (e.g., 100 mM KCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4).

2. Spectral Titration with H₂O₂:

- Setup: Dilute the purified probe to an optical density suitable for fluorescence measurement in a spectrophotometer.

- Baseline Reading: Acquire fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of the fully reduced probe.

- Titration: Add increasing concentrations of H₂O₂ (e.g., from 10 nM to 600 µM) to the cuvette. After each addition, incubate for a fixed time (e.g., 2-5 minutes) and record the full fluorescence spectrum.

- Data Analysis: Plot the fluorescence intensity (or ratio of intensities at two wavelengths) against the H₂O₂ concentration. Fit the data to a sigmoidal curve to determine the apparent Kd and dynamic range.

3. Selectivity Assay:

- Procedure: Incubate separate aliquots of the purified probe with various potential interfering oxidants and compounds (e.g., 1 mM MAHMA-NONOate for NO, a xanthine/xanthine oxidase system for superoxide, 1 mM SIN-1 for peroxynitrite, 1 mM oxidized glutathione (GSSG)).

- Measurement: Monitor the fluorescence signal before and after addition. A specific H₂O₂ probe should show minimal response to these other compounds.

Protocol: Functional Assessment of Cysteine Vulnerability in Glutaredoxin

This protocol, inspired by studies on glutaredoxin (GLRX), outlines a method to identify which cysteine residues are critical for activity and most susceptible to oxidation, a key step in probe optimization [21].

1. Site-Directed Mutagenesis:

- Design: Design cysteine-to-serine (Cys-to-Ser) mutants for each cysteine residue in the protein of interest, both individually and in combination.

- Verification: Verify all mutations by DNA sequencing.

2. Activity Assay under Controlled Redox Conditions:

- Recombinant Protein: Express and purify the wild-type (WT) and all mutant proteins.

- Substrate Preparation: Use a glutathionylated substrate for activity measurement. A common model is Eosin-glutathionylated-BSA (E-GS-BSA).

- Assay Setup: In a microplate reader, mix the protein (WT or mutant, at a fixed concentration) with the E-GS-BSA substrate in a deglutathionylation buffer. Omit the GSH/GR/NADPH recycling system to avoid confounding effects. Instead, include a low concentration of DTT (e.g., 5 µM) to maintain a minimal reducing environment without directly reducing the substrate.

- Kinetic Measurement: Continuously monitor the increase in fluorescence (dequenching) as eosin-labeled glutathione is released from the substrate. Compare the initial rates of the mutants to the WT protein.

3. Susceptibility to Oxidative Inactivation:

- Pre-incubation: Pre-incubate the WT and mutant proteins with a range of concentrations of H₂O₂ or GSSG.

- Residual Activity Measurement: After pre-incubation, dilute the reaction mixture and measure the remaining deglutathionylation activity using the assay described above.

- Data Analysis: Plot residual activity vs. oxidant concentration. Mutants that show resistance to inactivation at specific sites indicate those cysteines are critical vulnerability points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Redox Probe Fabrication and Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|

| H₂O₂ | Primary oxidant for sensor calibration and challenge. | Prepare fresh dilutions from high-purity stock for accurate concentration. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing agent for maintaining probe in reduced state and testing reversibility. | Often used at low concentrations (e.g., 5 µM) in activity assays. |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol (2-ME) | Reducing agent used in protein purification buffers. | Helps prevent non-specific oxidation of cysteine residues during purification. |

| E-GS-BSA (Eosin-Glutathionylated BSA) | Model substrate for measuring deglutathionylation activity. | Fluorescence increases upon deglutathionylation, enabling kinetic assays [21]. |

| diE-GSSG (Dye-labeled GSSG) | Model substrate for measuring oxidoreductase activity. | Used to probe enzyme kinetics without a GSH recycling system [21]. |

| NOC-7 / MAHMA-NONOate | Nitric oxide (NO) donors. | Used for testing sensor selectivity and for characterizing NO-specific probes like geNOps [20]. |

| SIN-1 | Simultaneous generator of superoxide and nitric oxide, producing peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻). | Used in selectivity assays to challenge probes with a potent biological oxidant [17]. |

| Xanthine/Xanthine Oxidase | Enzymatic system for generating superoxide anion (O₂•⁻). | Used to test sensor specificity and exclude superoxide sensitivity [17]. |

Cellular redox homeostasis, governed by key molecular pairs like glutathione (GSH/GSSG), NAD⁺/NADH, and reactive oxygen species such as H₂O₂, is fundamental to regulating signal transduction, gene expression, and metabolic pathways. Disruption of this delicate balance is implicated in numerous pathologies, including cancer, where aberrant metabolism leads to the accumulation of "oncometabolites." The accurate measurement of these redox couples in living systems has been transformed by the development of genetically encoded fluorescent probes, which enable real-time, subcellular monitoring of redox dynamics with high specificity and minimal cellular disruption. This application note details quantitative assessments, experimental protocols, and key reagent solutions for investigating these critical redox targets, providing a framework for their application in basic research and drug discovery.

Glutathione (GSH/GSSG)

The GSH/GSSG couple represents the primary redox buffer in aerobic cells, with the ratio serving as a crucial indicator of cellular oxidative stress. Under normal conditions, reduced glutathione (GSH) constitutes up to 98% of the cellular pool, but this ratio decreases under pathological stress [22].

Quantitative Profile of the GSH/GSSG Redox Couple

Table 1: Quantitative Profile of the GSH/GSSG Redox Couple

| Parameter | Value / Range | Context / Condition | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cellular GSH | Millimolar (mM) range | Tissue concentrations [22] | HPLC |

| Physiological GSH/GSSG Ratio | ~98:2 to 90:10 [22] | Normal conditions | Enzymatic recycling assay |

| Pathological GSH/GSSG Ratio | Reduced | Neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's, Parkinson's) [22] | Enzymatic recycling assay |

| HPLC Limit of Detection (LOD) | GSH: 0.34 µM; GSSG: 0.26 µM | Optimized reverse-phase HPLC with fluorescence detection [23] | HPLC with fluorescence |

| HPLC Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | GSH: 1.14 µM; GSSG: 0.88 µM | Optimized reverse-phase HPLC with fluorescence detection [23] | HPLC with fluorescence |

| Assay Linear Range | GSH: 0.1 µM - 4 mM; GSSG: 0.2 µM - 0.4 mM | r² = 0.998 for GSH, r² = 0.996 for GSSG [23] | HPLC with fluorescence |

Detailed Protocol: HPLC-Based Measurement of GSH and GSSG

This protocol is optimized to prevent auto-oxidation of GSH, a common source of inaccuracy [23].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Biological Sample: Tissue homogenate or cell lysate.

- Stabilization Reagent: N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) or 2-vinylpyridine to prevent GSH auto-oxidation.

- Extraction Buffer: Ice-cold metaphosphoric acid or perchloric acid.

- Derivatization Agent: O-phthaldialdehyde (OPA).

- HPLC System: Equipped with a fluorescence detector and a C18 reverse-phase column.

- Mobile Phases: Buffer A: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water; Buffer B: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in methanol or acetonitrile.

Procedure:

- Sample Stabilization and Extraction:

- Homogenize tissue or lyse cells in the presence of a stabilization reagent like NEM to rapidly alkylate and preserve reduced GSH.

- Precipitate proteins using ice-cold acidic extraction buffer (e.g., 3-5% metaphosphoric acid).

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C) and collect the acid-soluble supernatant containing glutathione.

Derivatization:

- Adjust the pH of the supernatant to an optimal range for OPA derivatization (typically pH 8-9).

- Incubate the sample with OPA reagent in the dark for a defined period (e.g., 15-30 minutes) to form the highly fluorescent GSH-OPA adduct.

Chromatographic Separation and Detection:

- Inject the derivatized sample onto a reverse-phase C18 column.

- Elute using a gradient method, increasing the percentage of organic solvent (Buffer B) over time.

- Monitor fluorescence with excitation/emission wavelengths typically set at 340/420 nm.

- Identify and quantify GSH and GSSG by comparing retention times and peak areas to those of authentic standards.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the concentrations of GSH and GSSG from their respective standard curves.

- Determine the GSH/GSSG ratio and the redox potential.

Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂)

H₂O₂ is a key redox signaling molecule involved in immune response, cell migration, and metabolic regulation. Genetically encoded probes have revolutionized the real-time visualization of H₂O₂ dynamics.

Quantitative Profile of H₂O₂ Probes

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Genetically Encoded H₂O₂ Probes

| Probe Name | Key Feature | Dynamic Range / Sensitivity | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP2-PRXIIB | Fused to endogenous plant H₂O₂ sensor PRXIIB; superior sensitivity and conversion kinetics [24] | Enhanced responsiveness compared to roGFP2-Orp1 [24] | Real-time monitoring of H₂O2 during abiotic/biotic stress and pollen tube growth in plants [24] |

| HyPer7 | Ultrasensitive, pH-stable, ratiometric; based on OxyR from N. meningitidis [25] | Ultrasensitive (designed for ultra-low concentrations), bright, ultrafast [25] | Visualizing H₂O2 diffusion from mitochondrial matrix and gradients in cell migration and wounded tissue [25] |

Detailed Protocol: Live-Cell Imaging with H₂O₂ Probes

This protocol outlines the use of genetically encoded probes like HyPer7 or roGFP2-PRXIIB for ratiometric imaging of H₂O₂ in living cells.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Genetically Encoded Probe: Plasmid DNA for HyPer7, roGFP2-PRXIIB, or similar.

- Cell Culture: Appropriate cell line or primary cells.

- Transfection Reagent: For plasmid delivery.

- Imaging System: Confocal or widefield fluorescence microscope capable of ratiometric imaging and time-series acquisition.

- Stimuli/Inhibitors: E.g., growth factors, pathogens (for immune activation), or peroxide-scavenging agents like catalase.

Procedure:

- Probe Expression:

- Transfert cells with the plasmid encoding the H₂O₂ probe. For subcellular resolution, use constructs with localization sequences (e.g., for cytosol, nuclei, mitochondria, chloroplasts).

- Generate stable cell lines for consistent long-term experiments.

Ratiometric Imaging:

- Place transfected cells in an appropriate imaging chamber on the microscope stage.

- For HyPer7 or roGFP2-based probes, acquire sequential images using two excitation wavelengths (e.g., 488 nm and 405 nm) while collecting emission at a single wavelength (e.g., 525 nm).

- Maintain controlled environmental conditions (temperature, CO₂).

Experimental Stimulation and Data Acquisition:

- Acquire a stable baseline ratio for several minutes.

- Apply the experimental stimulus (e.g., a drug, nutrient, or pathogen-associated molecular pattern) without moving the sample.

- Continue time-lapse imaging to capture dynamic changes in the fluorescence ratio.

Data Analysis:

- For each time point, calculate the ratio of fluorescence (e.g., F₄₈₈/F₄₀₅ for HyPer7).

- Normalize the ratios to the initial baseline value (ΔR/R₀) or present as the 488/405 nm ratio over time.

- The ratio is a relative measure of H₂O₂ levels. For absolute concentration, perform an in-situ calibration at the end of the experiment using bolus H₂O₂ and a reducing agent like DTT.

NAD⁺/NADH

The NAD⁺/NADH redox couple is a central regulator of cellular energy metabolism and a key indicator of the metabolic state. The SoNar sensor is a prime example of a genetically encoded tool for monitoring this couple.

Quantitative Profile of NAD⁺/NADH and the SoNar Sensor

Table 3: Quantitative Profile of NAD⁺/NADH and the SoNar Sensor

| Parameter | Value / Range | Context / Condition | Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Intracellular NAD⁺ + NADH | Hundreds of micromolar (µM) [26] | Mammalian cells | Biochemical assay |

| SoNar Apparent Kd | NAD⁺: ~5.0 µM; NADH: ~0.2 µM [26] | pH 7.4 | Fluorescence titration |

| SoNar Dynamic Range | Up to 15-fold ratio change [26] | Between saturated NAD⁺ and NADH states | Ratiometric fluorescence |

| SoNar Apparent K (NAD⁺/NADH) | ~40 [26] | The NAD⁺/NADH ratio for half-maximal response | Ratiometric fluorescence |

| Cancer Cell NAD⁺/NADH Ratio | Significantly lower | H1299 and other cancer cell lines vs. non-cancer cells [26] | SoNar sensor imaging |

| Electrochemical Sensor LOD | 3.5 µM | In mouse whole blood [27] | Electrocatalytic sensor with NPQD monolayer |

Detailed Protocol: Monitoring NAD⁺/NADH Redox State with SoNar

SoNar is a genetically encoded, intensely fluorescent, ratiometric sensor with high pH resistance, ideal for tracking cytosolic NAD⁺ and NADH redox states [26].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- SoNar Sensor: Plasmid for mammalian expression.

- Cell Culture: Cancer and non-cancer cell lines for comparison (e.g., H1299, HEK293).

- Metabolic Modulators: Pyruvate (e.g., 10 mM), Lactate (e.g., 10-20 mM), Oxamate (LDH inhibitor, e.g., 20-50 mM), 3-Bromopyruvate (glycolysis inhibitor, e.g., 50-100 µM).

- Imaging System: Fluorescence microscope or plate reader capable of ratiometric measurements (excitation: 420 nm and 485 nm, emission: ~525 nm).

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation:

- Stably express the SoNar sensor in your cell lines of interest.

Ratiometric Measurement:

- For microscopy: Image cells using dual-excitation ratiometric imaging (420/485 nm).

- For high-throughput screening: Use a fluorescent microplate reader in ratiometric mode.

Metabolic Perturbation Experiments:

- Acquire a stable baseline fluorescence ratio.

- Apply metabolic modulators to observe real-time changes in the NAD⁺/NADH ratio.

- Example: Pyruvate addition should cause a rapid decrease in the SoNar ratio (indicating a more reduced state), while the LDH inhibitor oxamate should increase it (indicating a more oxidized state) [26].

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the 420/485 nm excitation ratio over time.

- The ratio reports on the NAD⁺/NADH ratio. A higher SoNar ratio indicates a more oxidized state (higher NAD⁺/NADH), while a lower ratio indicates a more reduced state (lower NAD⁺/NADH).

Oncometabolites

Oncometabolites are metabolites that accumulate to supraphysiological levels due to metabolic alterations in cancer cells. They drive tumorigenesis by inducing genetic and epigenetic changes and modifying the tumor microenvironment [28] [29].

Quantitative and Functional Profile of Key Oncometabolites

Table 4: Key Oncometabolites: Origins, Pathogenic Roles, and Measurement

| Oncometabolite | Origin in Cancer | Key Pathogenic Roles & Mechanisms | Common Analysis Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| L-Lactate | Aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) [28] | - Suppresses immune response.- Stimulates angiogenesis via HIF-1α stabilization and NF-κB/IL-8 activation.- Acidifies the tumor microenvironment [29]. | LC-MS, enzymatic assays |

| D-2-Hydroxyglutarate (D-2HG) | Neomorphic mutations in IDH1/2 [28] | - Competitively inhibits α-KG-dependent dioxygenases.- Alters epigenetics (DNA/histone methylation).- Blocks cellular differentiation [28]. | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS |

| Succinate | Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDH) mutations or dysregulation [28] | - Inhibits HIF prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs), stabilizing HIF-1α.- Promotes epigenetic remodeling.- induces cytokine-driven inflammation [28] [29]. | LC-MS, enzymatic assays |

| Fumarate | Fumarate Hydratase (FH) mutations [28] | - Inhibits PHDs, stabilizing HIF-1α.- Covalently modifies cysteine residues (succination) in proteins like KEAP1, activating Nrf2.- Causes epigenetic changes [28] [29]. | LC-MS, NMR |

Detailed Protocol: Analyzing Oncometabolite-Driven Pathways

Studying oncometabolites involves measuring their levels and quantifying their downstream functional impacts on the epigenome and cellular signaling.

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Biological Samples: Isogenic cell lines (e.g., with/without IDH1/2 mutation), tumor tissue, patient serum.

- Extraction Solvent: 80% methanol, ice-cold.

- Mass Spectrometry System: LC-MS/MS with appropriate columns (e.g., HILIC for polar metabolites).

- Antibodies: For HIF-1α, histone methylation marks (e.g., H3K9me3), DNA methylation analysis kit.

- Angiogenesis Assay Kits: For measuring VEGF levels or endothelial tube formation.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Metabolite Extraction:

- Quench cell metabolism rapidly by washing with ice-cold saline and adding 80% methanol.

- Scrape cells, vortex, and incubate at -80°C for 1 hour.

- Centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C) and collect the supernatant for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Targeted Metabolomic Analysis:

- Analyze the extracts using a targeted LC-MS/MS method optimized for polar organic acids.

- Quantify oncometabolites by comparing peak areas to those of authentic standards of known concentration.

Functional Downstream Analysis:

- HIF-1α Stabilization: Perform western blotting for HIF-1α on nuclear extracts from cells grown under normoxic conditions.

- Epigenetic Alterations: Perform chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) for specific histone marks or analyze global DNA methylation patterns.

- Angiogenesis Assays: Measure VEGF secretion by ELISA or co-culture cancer cells with endothelial cells to assess tube formation.

Data Integration:

- Correlate oncometabolite levels with the magnitude of the functional readouts (e.g., HIF-1α protein levels, specific histone methylation marks) to establish causative links.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Redox and Metabolic Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Utility | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SoNar Sensor | Genetically encoded, ratiometric sensor for NAD⁺/NADH ratio [26] | High-throughput screening for agents targeting tumor metabolism; real-time monitoring of cytosolic redox state. |

| HyPer7 Probe | Ultrasensitive, pH-stable, genetically encoded indicator for H₂O₂ [25] | Visualizing H₂O₂ gradients in cell migration and mitochondrial function. |

| roGFP2-PRXIIB Probe | Genetically encoded probe fused to endogenous plant peroxidase for H₂O₂ [24] | Monitoring subcellular H₂O₂ dynamics during immune responses and stress in plants. |

| 4-ATP / NPQD Monolayer | Electrocatalytic surface for electrochemical NADH detection [27] | Fabrication of disposable electrocatalytic sensors for NADH detection in whole blood. |

| OPA (o-phthaldialdehyde) | Derivatizing agent for glutathione to form a fluorescent adduct [23] | HPLC-based quantification of GSH and GSSG with fluorescence detection. |

| N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Thiol-alkylating agent | Sample stabilization to prevent GSH auto-oxidation during GSH/GSSG ratio measurement. |

| Oxamate | Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) inhibitor | Experimentally modulating the cytosolic NAD⁺/NADH ratio in live cells. |

| IDH1/2 Mutant Models | Cellular or animal models with mutant IDH1/2 genes [28] | Studying the effects of the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate on tumorigenesis and epigenetics. |

From DNA to Data: Fabrication Protocols and Live-Cell Imaging Applications

Cellular redox homeostasis, governed by the balance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and antioxidant systems, is a critical regulator of numerous physiological and pathological processes. Redox signaling, once considered primarily a source of oxidative damage, is now recognized as a key component of cellular communication, influencing growth-factor signaling, inflammation, and metabolic regulation [30]. One of the major effectors of ROS in redox signaling are thiol groups of cysteine residues in proteins, which can undergo reversible oxidative post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as S-sulfenylation, disulfide-bond formation, and further oxidation to S-sulfinylation and S-sulfonylation [30]. The reversibility of certain modifications like S-sulfenylation makes them particularly suitable for temporal signal transduction, analogous to phosphorylation events in other signaling cascades.

The emergence of genetically encoded fluorescent redox probes has revolutionized our ability to monitor these dynamic redox processes directly within living cells and specific subcellular compartments. Unlike synthetic probes that require loading into cells, genetically encoded probes are introduced as DNA constructs and expressed intracellularly, allowing for precise targeting to organelles and tissues of interest [31]. This review provides a comprehensive overview of the modular design principles, genetic construction strategies, and practical applications of these powerful research tools, with a focus on their implementation in drug discovery and basic research contexts.

Principal Classes of Genetically Encoded Redox Probes

Redox-Sensitive Fluorescent Proteins (roGFP and rxYFP)

Redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein (roGFP) and redox-sensitive yellow fluorescent protein (rxYFP) represent the foundational architectures for many genetically encoded redox probes. These probes were developed by introducing surface-exposed cysteine residues into the β-barrel structures of fluorescent proteins, positioned strategically to form reversible disulfide bonds in response to oxidation [31]. The oxidation status alters the chromophore environment, resulting in measurable fluorescence changes.