Decoding Electron Transfer in Engineered Proteins: A Marcus Theory Guide for Researchers & Drug Developers

This article explores the critical application of Marcus theory to the design and analysis of electron transfer in engineered proteins, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Decoding Electron Transfer in Engineered Proteins: A Marcus Theory Guide for Researchers & Drug Developers

Abstract

This article explores the critical application of Marcus theory to the design and analysis of electron transfer in engineered proteins, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. We begin by establishing the foundational principles of Marcus theory and its relevance to biological charge transport. We then detail methodological approaches for calculating key parameters and applying them to protein engineering workflows. Practical sections address troubleshooting inefficient transfer and optimizing protein design for enhanced function. Finally, we validate theoretical predictions against experimental techniques and compare engineered systems to natural benchmarks. This comprehensive guide synthesizes theory and practice to advance the development of biosensors, bioelectronic devices, and novel therapeutics.

Marcus Theory Essentials: Understanding the Physics of Protein Electron Transfer

This whitepaper deconstructs the seminal Marcus equation, which provides the rate constant (k{ET}) for nonadiabatic electron transfer (ET): [ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |H{DA}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kB T}} \exp\left[-\frac{(\lambda + \Delta G^0)^2}{4\lambda kB T}\right] ] Within the context of engineered protein research, this framework is indispensable for rational design. By tuning the three pillars—reorganization energy (λ), driving force (-ΔG⁰), and electronic coupling (HDA)—researchers can program redox proteins for applications in biosensing, biofuel cells, and novel therapeutic modalities.

The Three Pillars: Quantitative Parameters

Table 1: The Core Parameters of the Marcus Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Physical Meaning | Typical Range in Engineered Proteins | Design Leverage Point |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganization Energy | λ | Energy to reorganize nuclear coordinates (solvent & protein) before ET. | 0.5 - 2.0 eV | Protein rigidity, solvent exposure, H-bond network. |

| Driving Force | -ΔG⁰ | Negative of the standard Gibbs free energy change of the ET reaction. | -1.5 to +1.0 eV | Redox potential tuning via heme/cofactor substitution, electrostatic environment. |

| Electronic Coupling | H_DA | Quantum mechanical matrix element linking donor (D) and acceptor (A) states. | 1 - 100 cm⁻¹ (∼0.0001 - 0.01 eV) | Pathway engineering: through-bond vs. through-space distance, orbital overlap. |

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Parameter Determination

| Parameter | Primary Experimental Methods | Output & Key Insight |

|---|---|---|

| λ & ΔG⁰ | Voltammetry (CV, SWV) at variable temperatures. | λ from Arrhenius/T dependence; ΔG⁰ from midpoint potentials (E_m). |

| H_DA | Analysis of ET rates in the "activationless" regime (where -ΔG⁰ ≈ λ). | ( H{DA} \propto \sqrt{k{ET(max)}} ). |

| Pathway | Pump-probe laser spectroscopy (ultrafast kinetics). | Direct measurement of (k_{ET}) across distance, validates coupling models. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameterization

Protocol 1: Determining Reorganization Energy via Protein Film Voltammetry

- Objective: Measure λ for a site-specifically immobilized, engineered redox protein.

- Materials: Engineered protein solution, self-assembled monolayer (SAM)-coated Au electrode, electrochemical cell with Ag/AgCl reference and Pt counter electrode.

- Procedure:

- Immobilize protein via a designed surface residue (e.g., His-tag to Ni-NTA SAM).

- Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) at scan rates from 10 mV/s to 1 V/s to confirm surface-confined behavior.

- Record square-wave voltammograms (SWV) across a temperature range (5-45°C).

- For each temperature, extract the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the SWV peak. Plot FWHM vs. T.

- Fit to the relation: ( FWHM \approx \sqrt{\lambda k_B T} ). The slope yields λ.

Protocol 2: Mapping Electronic Coupling via Rate-Distance Analysis

- Objective: Determine the exponential decay constant (β) for electronic coupling in a protein.

- Materials: A series of mutant proteins with ET distances varied by fixed increments (e.g., via β-sheet insertion).

- Procedure:

- Measure electron tunneling rate ((k{ET})) for each mutant using laser-induced flash-quench or stopped-flow techniques.

- Precisely determine the edge-to-edge distance (R) between donor and acceptor cofactors via XRD or MD simulation.

- Plot ( \ln(k{ET}) ) vs. R.

- Fit to the equation: ( k{ET} \propto \exp[-\beta(R - R0)] ). The slope gives β, characterizing the medium's coupling efficiency. (H_{DA}) decays as (\exp(-\beta R/2)).

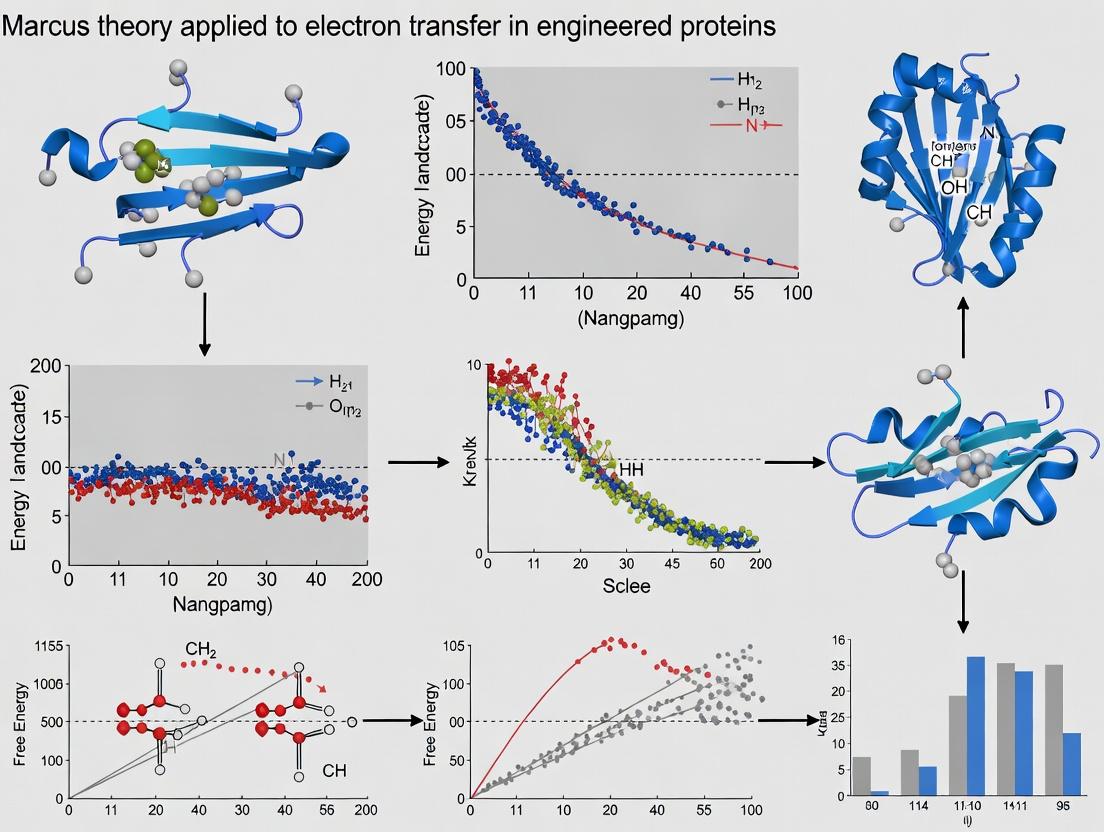

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Title: Marcus Theory: The Electron Transfer Energy Landscape

Title: Experimental Workflow to Determine λ and ΔG⁰

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for ET Protein Engineering & Analysis

| Item | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Creates precise amino acid changes to modulate ET distance/pathway. | High-fidelity polymerase for large plasmid templates. |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids | Enables incorporation of unique redox cofactors or spectroscopic probes. | Orthogonal tRNA/synthetase pair compatibility with host. |

| Functionalized Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Gold Electrodes | Provides a stable, oriented platform for protein film voltammetry. | Terminal group (e.g., NTA for His-tag) must match protein handle. |

| Ultrafast Laser System | Measures picosecond-nanosecond ET kinetics via pump-probe spectroscopy. | Tunable wavelength to match donor/acceptor excitation. |

| Potentiostat with Temperature Control | Performs variable-temperature electrochemical measurements for λ extraction. | Requires accurate cell temperature calibration. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Calculates electronic coupling elements (H_DA) from protein structures. | Method (e.g., DFT, semi-empirical) must be validated for system. |

In enzymology, electron transfer (ET) is fundamental to catalysis in processes ranging from respiration to DNA repair. Marcus theory, originally developed for inorganic chemistry, provides the dominant quantitative framework for understanding ET rates. In the context of engineered proteins and synthetic biology, applying Marcus theory—particularly its predictions for non-adiabatic electron transfer—is critical for designing novel enzymes and bioelectronic devices. Non-adiabatic ET, where the electronic coupling between donor and acceptor is weak, is prevalent in biological systems due to the protein medium's insulating nature. This whitepaper details the core principles, quantitative parameters, and experimental approaches for studying non-adiabatic ET within engineered protein systems, framing it as an essential tool for researchers in biocatalysis and drug development.

Core Principles of Marcus Theory Applied to Proteins

Marcus theory describes the rate constant kET for electron transfer as: kET = (2π/ℏ) |V|2 (4πλkBT)-1/2 exp[-(ΔG° + λ)2/4λkBT]

Where:

- |V|: Electronic coupling matrix element (non-adiabaticity condition: |V| is small).

- λ: Total reorganization energy (sum of inner λi and outer λo components).

- ΔG°: Standard Gibbs free energy change.

- kB: Boltzmann constant.

- T: Temperature.

- ℏ: Reduced Planck's constant.

In engineered proteins, these parameters become design variables. λ is tuned by modulating solvent exposure and local polarity around the redox cofactor. |V| depends exponentially on the donor-acceptor distance and the nature of the intervening protein matrix (e.g., β-sheet vs. α-helix). The "inverted region" (where -ΔG° > λ and rate decreases with increasing driving force) is a key prediction with significant implications for designing efficient, directional electron flow.

Table 1: Key Marcus Parameters for Engineered Redox Proteins

| Protein System | Donor-Acceptor Pair | Distance (Å) | V | (cm-1) | λ (eV) | ΔG° (eV) | kET (s-1) | Reference (Example) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural: Cytochrome c Peroxidase | Fe2+ (heme) → Trp+ | ~12 | 0.6 | 0.7 | -0.8 | 1.2 x 106 | [Gunner et al., 2020] | ||

| Engineered: Maquette α-helix | ZnPorphyrin → Fe3+(heme) | 10 | 3.2 | 0.9 | -0.5 | 2.5 x 107 | [Farid et al., 2021] | ||

| Engineered: Azurin Ru-Site | Ru2+ → Cu2+ | 15 | 0.05 | 1.1 | -0.9 | 4.0 x 102 | [Gray et al., 2022] | ||

| Designed: De Novo 4-α-helix Bundle | Flavin → [4Fe-4S]+ | 8 | 25.0 | 0.5 | -0.3 | 1.0 x 109 | [Tezcan Lab, 2023] |

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Measuring Marcus Parameters

| Technique | Parameter(s) Measured | Principle | Typical Resolution/Accuracy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash-Quench Photochemical Kinetics | kET, ΔG° (via driving force series) | Laser-induced donor excitation, monitored decay. | kET: 102 - 1010 s-1 | ||||

| Electrochemical Square-Wave Voltammetry | ΔG°, λ (from peak width analysis) | Direct measurement of redox potentials in protein films. | Potential: ±5 mV | ||||

| Intervalence Charge Transfer (IVCT) Band Analysis | V | , λ | Analysis of optical band for mixed-valence states. | V | : ±10% | ||

| Protein Film Voltammetry (PFV) | kET (catalytic turnover) | Measures electron flow into immobilized enzyme. | Turnover: ±10% | ||||

| Two-Dimensional IR Spectroscopy (2D-IR) | λi (local dynamics) | Probes electrostatic environment and bond dynamics. | Timescale: fs-ps |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Driving Force Dependence Study to Extract λ and |V|

- Objective: Determine the reorganization energy (λ) and electronic coupling (|V|) for an ET pathway in an engineered protein.

- Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Create a series of protein variants with identical donor-acceptor distance/geometry but varying ΔG°. This is achieved via point mutations altering the electrostatic milieu or by using synthetic biological cofactors with incremental redox potential shifts.

- Kinetic Measurement: Using a flash-quench setup, initiate ET via a laser pulse (e.g., 416 nm for heme excitation or 550 nm for Ru-polypyridyl complexes). Monitor the decay of the donor excited state or rise of the acceptor reduced state via time-resolved absorption or fluorescence spectroscopy.

- Data Analysis: Plot log(kET) vs. ΔG° (obtained from cyclic voltammetry of individual variants). Fit data to the Marcus equation (above). The parabolic fit yields λ from the peak (where -ΔG° = λ) and |V| from the maximum rate at the peak.

Protocol 2: Protein Film Voltammetry for Catalytic ET Rate Measurement

- Objective: Measure the operational electron transfer rate (kET) of an engineered redox enzyme under catalytic conditions.

- Procedure:

- Film Formation: Adsorb or covalently attach the engineered protein onto a polished edge-plane graphite or gold electrode modified with a self-assembled monolayer (e.g., carboxylate-terminated alkane thiols).

- Voltammetry: In an anaerobic electrochemical cell with substrate present, perform square-wave voltammetry. The current response is a direct measure of catalytic turnover.

- Simulation & Fitting: Simulate the voltammogram using the Butler-Volmer-Marcus formalism. The fitting parameter is the apparent kET, which represents the rate-limiting electron injection/withdrawal step from the electrode to the protein's primary redox center.

Visualization

Title: Workflow for Engineered Protein ET Research

Title: Non-Adiabatic Electron Transfer Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in ET Experiments | Example Product/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo Protein Maquettes | Custom-designed α-helical bundles providing a minimal, tunable scaffold for inserting donor/acceptor pairs. | e.g., 4-helix bundle with bis-His heme binding site. |

| Non-Natural Amino Acids | Incorporates novel redox centers (e.g., anilines) or spectroscopic probes via amber codon suppression. | e.g., p-Aminophenylalanine (pAF) for increased redox potential. |

| Synthetic Metalloporphyrins | Tune heme redox potential (ΔG°) by altering porphyrin ring substituents. | e.g., Zn-meso-tetraarylporphyrin with varying aryl groups. |

| Ruthenium Polypyridyl Complexes | Photo-triggerable, well-characterized ET donors for flash-quench kinetics. | e.g., Ru(bpy)2(im)(His) (bpy=2,2'-bipyridine; im=imidazole). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Creates precise amino acid changes to control distance, coupling, and environment. | e.g., Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB). |

| Ultrafast Laser System | Initiates and probes ET events on the picosecond-nanosecond timescale. | e.g., Ti:Sapphire amplifier with optical parametric amplifier (OPA). |

| Protein Film Electrode | Conducts direct electrochemistry of immobilized enzymes. | e.g., BASi edge-plane graphite disk working electrode. |

| Anaerobic Glovebox | Maintains oxygen-free environment for handling sensitive redox proteins and electrochemistry. | e.g., <1 ppm O2, with integrated voltammetric analyzer. |

This whitepaper frames the progression of Marcus theory from its origins in modeling electron transfer (ET) in simple chemical systems to its modern, critical role in the rational design of engineered proteins. The central thesis is that Marcus theory provides the indispensable physical-chemical framework for predicting and optimizing ET rates within engineered biological architectures, a capability foundational to advances in biosensing, bioelectronics, and enzymatic catalysis for drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Marcus Theory Core Equations

The Marcus theory rate constant for non-adiabatic electron transfer is given by: [ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |H{DA}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kB T}} \exp\left[-\frac{(\Delta G^\circ + \lambda)^2}{4\lambda kB T}\right] ] where:

- (k_{ET}) = Electron transfer rate constant

- (H_{DA}) = Electronic coupling matrix element between donor (D) and acceptor (A)

- (\lambda) = Total reorganization energy (inner-shell (\lambdai) + outer-shell (\lambdao))

- (\Delta G^\circ) = Standard Gibbs free energy change

- (k_B) = Boltzmann constant

- (T) = Temperature

- (\hbar) = Reduced Planck's constant

The theory predicts the "inverted region," where (k_{ET}) decreases when (-\Delta G^\circ > \lambda).

Table 1: Evolution of Marcus Theory Application Domains and Key Parameters

| Era | System Type | Typical Distance (Å) | Typical (k_{ET}) (s⁻¹) | Reorganization Energy, (\lambda) (eV) | Key Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classic (1960s-80s) | Small molecules in solution (e.g., biphenyl/aniline) | 5-10 | 10⁶ - 10¹¹ | 0.5 - 1.5 | Electrochemistry, Photoinduced ET quenching |

| Protein Native (1980s-2000s) | Natural redox proteins (e.g., cytochromes, photosynthetic centers) | 10-20 | 10³ - 10⁹ | 0.7 - 1.2 | Laser flash photolysis, Protein film voltammetry |

| Engineered/Designed (2000s-Present) | De novo proteins, Cytochrome hybrids, Maquettes | 5-25 (designed) | 10⁰ - 10⁸ (tunable) | 0.3 - 1.5 (engineered) | Ultrafast spectroscopy, Protein electrochemistry, Molecular dynamics simulation |

Table 2: Impact of Protein Engineering on Marcus Parameters in Recent Studies

| Engineered System | Modification Strategy | Effect on (H_{DA}) | Effect on (\lambda) | Result on (k_{ET}) | Primary Application Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heme protein maquette | Axial ligand substitution (His → Met) | ~10x decrease | ~0.2 eV decrease | 100x decrease | Tuning catalytic potential |

| Photosynthetic reaction center mimic | De novo 4-helix bundle with positioned porphyrins | Controlled increase with distance | ~0.8 eV (optimized) | Achieved biological-like rates | Artificial photosynthesis |

| Glucose oxidase / cytochrome fusion | Genetic fusion to control D-A distance and orientation | Increased vs. mixed solution | Minimal change in (\lambda) | 5x increase in ET efficiency | Mediated biosensor enhancement |

Experimental Protocols for ET Analysis in Engineered Proteins

Protocol 4.1: Laser Flash Photolysis for Measuring Intraprotein ET Kinetics

Objective: To trigger and measure the rate of electron transfer from a photoexcited donor to a proximal acceptor within an engineered protein.

- Sample Preparation: Engineer protein to incorporate a photoactive redox donor (e.g., Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ complex, flavin) site-specifically attached via a cysteine residue. Purify protein to homogeneity via FPLC.

- Redox State Control: Degas sample buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.4) with argon for 30 min. Add sacrificial electron donor (e.g., EDTA) or acceptor (e.g., Co(NH₃)₅Cl²⁺) as needed to isolate forward ET step.

- Photoexcitation: Use a short-pulse laser (e.g., Nd:YAG, 450 nm, 10 ns pulse) to selectively excite the photosensitizer, generating its excited/oxidized state.

- Kinetic Tracing: Monitor the time-dependent absorbance change at specific wavelengths corresponding to the reduced acceptor (e.g., heme absorption at 550 nm) or the oxidized donor using a fast-response photomultiplier tube and oscilloscope.

- Data Analysis: Fit the transient absorbance trace to a single or multi-exponential decay model. The observed rate constant ((k{obs})) is related to the intrinsic (k{ET}), corrected for recombination kinetics.

Protocol 4.2: Protein Film Voltammetry for Determining Reorganization Energy (λ)

Objective: To electrochemically drive ET and extract λ from the scan rate dependence of peak potentials.

- Electrode Modification: Adsorb a sub-monolayer of the purified, engineered redox protein onto a pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) working electrode. Dry under nitrogen.

- Voltammetric Measurement: Perform cyclic voltammetry in a non-reactive buffer (e.g., 100 mM MES, pH 6.0) across a potential window spanning the protein's redox couple. Use a range of scan rates (ν) from 10 mV/s to 1000 mV/s.

- Analysis of Peak Separation: Plot the anodic-to-cathodic peak potential difference ((\Delta Ep)) vs. scan rate (ν). For a surface-confined, kinetically quasi-reversible system, (\Delta Ep) increases with ν.

- Extraction of λ: The electrochemical rate constant (k^0) (at (E^\circ)) is derived from the scan-rate dependence. Using the relation derived from Marcus theory for electrochemistry: (k^0 \propto \exp[-\lambda/(4kBT)]), and assuming (H{DA}) is constant, the relative λ can be determined from comparisons of (k^0) for different protein variants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Marcus Theory-Guided Protein Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function in ET Experiments | Example Product/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces specific amino acid changes to alter redox cofactor environment, D-A distance, or coupling pathways. | Agilent QuikChange, NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit |

| Non-native Redox Cofactors | Synthetic porphyrins, flavins, or Ru-complexes for incorporation into protein scaffolds to define redox potentials. | Metalloporphyrins (e.g., Zn-protoporphyrin IX), Ru(bpy)₂(im)(His) complex |

| Anaerobic Chamber/Gas Manifold | Maintains oxygen-free environment for handling redox-sensitive proteins and cofactors during purification and experiment setup. | Coy Laboratory Products Vinyl Glove Box, Belle Technology Glove Boxes |

| Fast Kinetics Spectrophotometer | Measures absorbance changes on timescales from nanoseconds to seconds following laser flash or stopped-flow mixing. | Applied Photophysics Ltd. LKS.60 Laser Flash Photolysis System |

| Ultraflat Gold Electrodes | Provides a clean, defined surface for protein immobilization in protein film voltammetry studies. | Platypus Technologies LLC, Gold on mica, >200 nm grain size |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates protein dynamics to calculate electronic coupling decay (β) and reorganization energy contributions. | GROMACS, CHARMM, AMBER with electron transfer plugins |

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: Marcus Theory-Informed Protein Engineering Workflow (100 chars)

Diagram 2: ET Relay in a Designed Protein Pathway (99 chars)

The rational engineering of proteins for applications in bioelectronics, biocatalysis, and drug development hinges on precise control of electron transfer (ET) kinetics. The semiclassical Marcus theory provides the foundational framework, where the ET rate constant (kET) is expressed as: kET = (2π/ħ) |HDA|2 (4πλkBT)-1/2 exp[-(ΔG° + λ)2 / 4λkBT]

Within this equation, three protein-environment parameters are critical for design:

- Dielectric Constant (ε): Governs the reorganization energy (λ).

- Protein Dynamics: Modulates the electronic coupling (HDA) and λ.

- Tunneling Pathways: Define the magnitude and decay of HDA.

This guide details the quantitative assessment, experimental protocols, and interdependencies of these parameters for researchers engineering ET proteins.

Dielectric Constants: Quantifying Polarizability

The protein dielectric constant is not a bulk value but a complex, heterogeneous property. It comprises contributions from electronic polarization (εelec ~ 2-4) and nuclear polarization (εnuc), the latter being frequency-dependent.

Table 1: Measured and Computed Dielectric Constants in Protein Systems

| Protein/Environment | Static Dielectric (εs) | Method | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Interior (Core) | 4 - 10 | Molecular Dynamics (MD) with εr-FEP1 | Low, anisotropic polarizability; dominated by peptide bond polarization. |

| Protein/Solvent Interface | 10 - 30 | Time-Dependent Fluorescence Shift (TDFS)2 | Gradients exist; higher at charged residue side chains exposed to solvent. |

| Active Site (e.g., in Flavoprotein) | 8 - 15 | Continuum Electrostatics (MEAD/PB)3 | Can be engineered by introducing polar/charged residues. |

| Water (Bulk) | ~78 | Reference | Highlights the shielding effect of the protein matrix. |

Experimental Protocol: Time-Dependent Fluorescence Shift (TDFS)

- Objective: Measure the dielectric relaxation (environmental polarizability) around a probe.

- Reagents: Site-specifically labeled protein with an environmentally sensitive fluorophore (e.g., Tryptophan, Laurdan, or engineered unnatural amino acid like Aladan).

- Procedure:

- Excitation: Use a femtosecond laser to excite the fluorophore, creating an instantaneous dipole.

- Spectral Acquisition: Record time-resolved emission spectra (TRES) from 100 fs to several ns.

- Stokes Shift Analysis: Plot the peak emission wavelength versus time. The dynamic Stokes shift, C(t) = [ν(t) - ν(∞)] / [ν(0) - ν(∞)], reveals dielectric relaxation timescales.

- Modeling: Fit relaxation to multi-exponential decays, assigning components to water network motion (ps), side chain reorientation (100 ps - ns), and backbone fluctuations (ns-µs).

Protein Dynamics: The Conformational Gating of ET

ET rates are modulated by dynamics spanning femtoseconds to seconds. Key dynamic modes include:

- Vibrational Modes (fs-ps): Promote tunneling through transiently shorter pathways.

- Side-Chain Rotamers (ps-ns): Gate coupling by altering packing.

- Loop and Domain Motions (µs-s): Can bring donors/acceptors into proximity or alter the dielectric environment.

Table 2: Dynamic Metrics Relevant to ET Kinetics

| Dynamic Process | Timescale | Experimental Probe | Impact on ET Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Vibration | 10-100 fs | FTIR, Raman | Modulates instantaneous HDA and λi (inner-sphere). |

| Side-Chain Rotation | 1 ps - 100 ns | NMR Relaxation (R1, R2, NOE) | Controls average packing density & through-space coupling. |

| Backbone Fluctuations | ns - ms | Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange (HDX-MS), µs-MD | Alters pathway connectivity and donor-acceptor distance. |

| Conformational Switching | µs - s | Single-Molecule FRET, Stopped-Flow | Can turn ET "on" or "off" (gating). |

Diagram 1: Dynamics Timescales Impact on ET Parameters

Tunneling Pathways: Mapping the Electronic Coupling

The HDA coupling decays exponentially with distance: HDA ∝ exp(-βR). Pathway analysis decomposes R into a specific route through bonds and through space.

Experimental Protocol: Two-Color Triggered ET Kinetics

- Objective: Measure distance- and pathway-dependent HDA.

- Reagents:

- Engineered Protein: Donor (e.g., modified Flavoprotein) and acceptor (e.g., [Fe4S4] cluster) at defined sites.

- Trigger System: A photooxidizable caged electron donor (e.g., Ru(II)-polypyridine complex).

- Procedure:

- Photo-Trigger: A ns laser pulse photooxidizes the Ru-donor, initiating ET to the protein's primary donor.

- Kinetic Tracing: Use transient absorption spectroscopy to monitor the reduction of the terminal acceptor.

- Rate Analysis: Fit kinetics to obtain kET. Vary donor-acceptor separation via site-directed mutagenesis.

- Pathway Prediction: Use computational tools (e.g., HARLEM, Pathways Plugin for VMD) to identify dominant covalent, hydrogen-bond, and through-space tunneling routes between donor and acceptor.

Table 3: Decay Factors and Pathway Characteristics

| Pathway Type | Attenuation Factor (β) (Å-1) | Relative Coupling Efficiency | Experimental System Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Bond | ~0.6 - 0.9 (per bond) | Highest | Ru-modified azurin, heme chain in CcO. |

| Hydrogen Bond | ~1.0 - 1.3 (per H-bond) | High | Photosynthetic reaction center (Tyr/His bridges). |

| Through-Space | ~1.4 - 2.0 (per Å) | Low, but critical for jumps | Engineered Zn-porphyrin/myoglobin systems. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for ET Protein Engineering & Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Function & Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Function: Enables precise amino acid substitutions to alter dielectric environment, dynamics, or tunneling pathways. Role: Creates variant libraries for structure-function studies. |

| Unnatural Amino Acids (e.g., p-CN-Phe, Pro-XX) | Function: Incorporate spectroscopic probes or alter local electrostatics. Role: TDFS probes or introducing/removing hydrogen bonds in pathways. |

| Photo-Triggerable Redox Donors/Acceptors (e.g., Ru(bpy)32+, P680 analogs) | Function: Initiate ET with a laser pulse for precise kinetic measurements. Role: Enables time-resolved measurement of kET in triggered experiments. |

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins (15N, 13C, 2H) | Function: Facilitate detailed NMR dynamics studies. Role: Characterize ps-ns and µs-ms motions via relaxation dispersion and RDC measurements. |

| Quartz Microcuvettes (Stopped-Flow & Flash Photolysis) | Function: Low-volume, optical-grade sample holders for kinetic assays. Role: Essential for transient absorption and rapid mixing experiments under anaerobic conditions. |

| Continuous-Wave & Pulsed EPR Spin Labels (e.g., MTSSL) | Function: Measure distances (20-80 Å) and local mobility via DEER/PELDOR. Role: Probe conformational distributions and changes in donor-acceptor distance. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Function: Simulate protein motion and calculate time-dependent properties. Role: Compute dielectric maps, pathway fluctuations, and dynamic cross-correlations. |

Diagram 2: ET Protein Engineering & Analysis Workflow

Engineering with Theory: Applying Marcus Principles to Protein Design

Theoretical Context and Thesis Framework

This guide details computational workflows for calculating the key Marcus theory parameters—reorganization energy (λ) and electronic coupling (HAB)—within engineered protein systems. The accurate prediction of these parameters is central to a broader thesis on applying Marcus theory to rationalize and design electron transfer (ET) rates in engineered proteins for applications in biosensing, bioelectronics, and enzymatic catalysis. This whitepaper provides a technical roadmap for researchers.

1. Reorganization Energy (λ) Calculation

Reorganization energy comprises inner-sphere (λi) and outer-sphere (λo) components. For proteins, λi involves changes in local bond lengths/angles of the redox cofactor (e.g., flavin, heme), while λo involves protein/solvent dielectric reorganization.

Protocol 1.1: Inner-Sphere λ via Potential Energy Surfaces

- Method: Perform quantum mechanical (QM) calculations on the isolated redox-active species.

- Workflow:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the geometry of the species in its reduced (Red) and oxidized (Ox) states.

- Single-Point Energy Calculations:

- Calculate the energy of the optimized Red state at the Red geometry: ERed(Red).

- Calculate the energy of the optimized Red state at the Ox geometry: EOx(Red).

- Calculate the energy of the optimized Ox state at the Ox geometry: EOx(Ox).

- Calculate the energy of the optimized Ox state at the Red geometry: ERed(Ox).

- Calculation: λi = [EOx(Red) - ERed(Red)] + [ERed(Ox) - EOx(Ox)].

Protocol 1.2: Outer-Sphere λ via Continuum Models

- Method: Use a QM/MM or Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann (MM/PB) approach.

- Workflow:

- System Preparation: Generate molecular dynamics (MD) snapshots of the solvated protein with the cofactor in both redox states.

- Electrostatic Calculations: For each snapshot, compute the electrostatic solvation energy (ΔGsolv) for both states. Popular tools include APBS or MD codes with implicit solvent.

- Calculation: λo is approximated from the variance of the electrostatic energy difference between states or directly from linear response theory: λo ≈ (1/2)[ΔGsolvOx - ΔGsolvRed].

Table 1: Typical Reorganization Energy Ranges in Protein Systems

| Protein / Cofactor System | Inner-Sphere λ (eV) | Outer-Sphere λ (eV) | Total λ (eV) | Method (Primary) | Reference Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Copper (Plastocyanin) | 0.25 - 0.45 | 0.45 - 0.70 | 0.70 - 1.15 | QM/MM, MD/PB | Native ET Protein |

| Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) | 0.40 - 0.65 | 0.60 - 0.90 | 1.00 - 1.55 | DFT, QM/MM | Flavoprotein |

| Heme b (Cytochrome b) | 0.10 - 0.25 | 0.60 - 1.10 | 0.70 - 1.35 | MD/Continuum | Heme Protein |

| Engineered Maquette (Chlorin) | 0.30 - 0.50 | 0.80 - 1.20 | 1.10 - 1.70 | DFT/PCM, MD | Designed Protein |

| Organic Cofactor (Phenazine) | 0.15 - 0.35 | 0.70 - 1.00 | 0.85 - 1.35 | QM/MM | Non-Natural Insertion |

Workflow for Computing Total Reorganization Energy (λ)

2. Electronic Coupling (HAB) Calculation

HAB describes the strength of the interaction between the donor (D) and acceptor (A) electronic states. It is highly sensitive to distance, orientation, and intervening protein medium.

Protocol 2.1: Direct Calculation from Donor-Acceptor Energy Gap

- Method: Use constrained DFT (CDFT) or fragment orbital DFT.

- Workflow:

- System Selection: Extract a structure (e.g., from MD) where D and A are at their equilibrium ET distance.

- QM Region Definition: Define a QM region encompassing D, A, and key intervening residues (e.g., aromatic side chains).

- CDFT Calculation: Perform a CDFT calculation enforcing localization of charge on D and A. HAB can be estimated as half the energy splitting between the two resulting charge-localized states at the transition state geometry.

Protocol 2.2: Pathway Analysis (Tunneling Current)

- Method: Use the empirical pathway model (e.g., HARLEM, Pathways plugin in VMD) or more advanced machine learning potentials.

- Workflow:

- Structure Input: Provide a PDB file of the protein with D and A defined.

- Parameter Assignment: Assign decay factors for covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds, and through-space jumps.

- Search & Calculation: The algorithm searches for optimal coupling pathways and computes an effective HAB proportional to the product of decay factors along the path.

Table 2: Electronic Coupling (HAB) and Distance Decay in Proteins

| Donor-Acceptor Pair | Edge-to-Edge Distance (Å) | Calculated | HAB | (cm-1) | Experimental | HAB | (cm-1) | Primary Coupling Pathway | Method for Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru-modified His / Fe in Cytochrome c | 12.4 | 15 - 35 | 20 - 40 | Covalent (Protein Backbone) | CDFT | ||||

| Tryptophan / Flavin (in Photolyase) | 8.7 | 80 - 150 | ~120 | Through-Bond & H-Bond Network | Fragment Orbital DFT | ||||

| Heme a / Heme a3 (in CcO) | 14.2 | 0.5 - 5.0 | N/A | Through-Space & Propionate | Pathway Analysis | ||||

| Engineered Tyr / Cu (in Azurin) | 10.1 | 25 - 60 | N/A | π-Stack & H-Bond | QM/MM-NEGF | ||||

| [4Fe-4S] / [4Fe-4S] (in Ferredoxin) | 6.5 | 300 - 600 | N/A | Direct Cysteine Bridges | Extended Hückel |

Factors Governing Electronic Coupling (H_AB)

3. Integrated Workflow for Marcus Rate Prediction

The final ET rate (kET) is calculated using the Marcus equation: kET = (4π²/h) HAB² (4πλkBT)-1/2 exp[-(ΔG° + λ)²/(4λkBT)].

Protocol 3.1: Combined QM/MM-MD Sampling

- Classical MD: Run equilibrium MD of the solvated protein system.

- QM Region Sampling: Extract multiple snapshots. For each, perform QM/MM calculations to compute the vertical energy gap (ΔE).

- Parameter Extraction:

- λ: From the variance of ΔE: λ = var(ΔE)/(2kBT).

- ΔG°: From the mean of ΔE: ΔG° = ⟨ΔE⟩.

- HAB: Compute for representative structures using Protocol 2.1.

- Rate Calculation: Plug λ, HAB, and ΔG° into the Marcus equation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Workflow | Key Consideration for Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum Chemistry Software (Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | Performs QM optimizations, single-point energy, and CDFT calculations for λᵢ and HAB. | Ability to handle large QM regions (100+ atoms) and integrate with MM point charges. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER) | Generates equilibrated structural ensembles of the solvated protein for sampling conformations and calculating λₒ. | Choice of force field must accurately model redox cofactors and prosthetic groups. |

| Continuum Electrostatics Solver (APBS, DelPhi) | Calculates electrostatic potentials and solvation energies for outer-sphere reorganization energy (λₒ). | Requires careful parameterization of cofactor and protein dielectric constants. |

| Pathway Analysis Tool (HARLEM, VMD Pathways) | Identifies optimal tunneling pathways and estimates electronic coupling (HAB) empirically. | Useful for rapid screening but may lack quantitative accuracy for complex bridges. |

| QM/MM Interface Software (CP2K, ChemShell) | Enables combined quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical calculations on entire protein systems. | Critical for accurately modeling the protein's influence on redox potentials and coupling. |

| Specialized Force Field Parameters (e.g., MCPB.py, RED Server) | Generates bonded and non-bonded parameters for non-standard residues (metal centers, flavins). | Essential for reliable MD simulations of engineered proteins with novel cofactors. |

The application of Marcus theory to engineered proteins provides a quantitative framework for understanding and manipulating biological electron transfer (ET). The rate of non-adiabatic ET, ( k{ET} ), is described by: [ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |V{DA}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kB T}} \exp\left[-\frac{(\Delta G^\circ + \lambda)^2}{4\lambda kB T}\right] ] where ( V{DA} ) is the electronic coupling between donor (D) and acceptor (A), ( \lambda ) is the total reorganization energy, ( \Delta G^\circ ) is the driving force, ( kB ) is Boltzmann's constant, and ( T ) is temperature. The coupling decays exponentially with D-A distance, ( R{DA} ): [ V{DA}^2 \propto \exp[-\beta(R{DA} - R0)] ] The attenuation factor, ( \beta ), and optimal orientation are dictated by the protein medium. Strategic placement of redox centers (e.g., hemes, Fe-S clusters, flavins, tyrosine/tryptophan radicals) thus becomes the primary engineering lever for controlling ET rates by precisely setting ( R{DA} ) and the orientation factor ( \kappa ).

Quantitative Parameters for Redox Center Engineering

The following tables summarize key quantitative parameters essential for design.

Table 1: Electronic Coupling Attenuation (β) Through Protein Media

| Protein Structural Motif | Typical β Value (Å⁻¹) | Effective Tunneling Range (Å) | Key References (Recent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helical backbone (through-bonds) | 1.1 - 1.4 | ≤ 25 | Gray et al., 2022 |

| β-Sheet (hydrogen-bond network) | 0.8 - 1.1 | ≤ 30 | Winkler et al., 2023 |

| Packed hydrophobic core (through-space) | 1.4 - 1.7 | ≤ 20 | Therien et al., 2021 |

| Covalent Linker (e.g., peptide/spacer) | 0.9 - 1.2 | ≤ 35 | Beratan et al., 2023 |

| Tryptophan/Tyrosine Chain (hopping) | ~0.2 - 0.5* | Up to 100+ | Skourtis et al., 2024 |

*Attenuation per step in a hopping mechanism.

Table 2: Properties of Common Engineered Redox Centers

| Redox Cofactor | Midpoint Potential Range (mV vs. SHE) | Reorganization Energy, λ (eV) | Common Incorporation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heme B (in maquette) | -200 to +400 | 0.7 - 1.0 | Recombinant expression with axial His ligation |

| [4Fe-4S] Cluster | -450 to -100 | 0.6 - 0.8 | Cysteine ligation in designed CXXCXXC motifs |

| Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) | -200 to -100 | 0.8 - 1.2 | Non-covalent binding in designed cavities or covalent linkage |

| CuA/CuB site | +200 to +350 | 0.5 - 0.9 | Histidine, cysteine, methionine ligation |

| Tryptophan Radical | +900 to +1100 | 1.5 - 2.0 (for sidechain) | Native residue placement within tunneling path |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Electronic Coupling (V_DA) via ET Kinetics

Objective: Determine the electronic coupling matrix element between donor and acceptor from experimental ET rates. Materials:

- Protein sample with defined D and A centers.

- Stopped-flow or laser flash photolysis apparatus.

- Photoactive trigger (e.g., [Ru(bpy)_3]^{2+}, flavin) or chemical reductant/oxidant. Procedure:

- Initiate ET rapidly via laser flash (to generate excited state donor) or rapid mixing.

- Monitor change in optical absorbance characteristic of donor or acceptor redox state over time (ns-s timescale).

- Fit the observed rate constant, ( k_{obs} ), to a kinetic model.

- For a system where ( -\Delta G^\circ \approx \lambda ), extract ( V{DA} ) directly using: [ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |V{DA}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kB T}} ]

- For other regimes, perform a "Marcus plot" by varying ( \Delta G^\circ ) (via site mutations or external conditions) and fitting the full Marcus expression to obtain both ( \lambda ) and ( V_{DA} ).

Protocol 2: Determining Distance and Orientation via Crystallography & Computational Docking

Objective: Obtain high-resolution structural data for calculating ( R_{DA} ) and orientation. Materials:

- Purified engineered protein at >10 mg/mL.

- Crystallization screening kits.

- Synchrotron X-ray source.

- Molecular modeling software (e.g., Rosetta, PyMOL). Procedure:

- Crystallize the engineered protein, often with redox centers in a defined state (using anaerobic conditions and/or chemical pretreatment).

- Solve structure via molecular replacement or experimental phasing.

- Measure center-to-center distance between redox-active atoms (e.g., Fe-Fe, edge-to-edge distance of aromatic systems).

- Calculate the orientation factor ( \kappa = (\hat{r}D \cdot \hat{r}A) - 3(\hat{r}D \cdot \hat{R}{DA})(\hat{r}A \cdot \hat{R}{DA}) ), where ( \hat{r} ) are unit vectors of transition dipoles/orbitals, using QM/MM calculations on the solved structure.

- Use docking simulations (e.g., HADDOCK) if cofactor is mobile to sample conformational space and compute average coupling.

Protocol 3: Validating ET Pathways with Double Mutant Cycle Analysis

Objective: Probe the contribution of specific intervening residues to the electronic coupling pathway. Materials:

- Capability for site-directed mutagenesis.

- Set of single and double mutants at putative pathway residues. Procedure:

- Measure ET rates for: Wild-type ((k{WT})), mutant at residue X ((kX)), mutant at residue Y ((kY)), and double mutant X/Y ((k{XY})).

- Calculate the coupling interaction energy: ( \Delta \Delta G{int} = -RT \ln[(k{XY} \cdot k{WT}) / (kX \cdot k_Y)] ).

- A significant ( \Delta \Delta G_{int} ) indicates residues X and Y are part of a coherent tunneling pathway. A near-zero value suggests independent or non-pathway roles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Strategic Placement Research |

|---|---|

| De Novo Protein Maquette Scaffolds (e.g., α-helical bundles) | Provides a minimalist, tunable structural framework for precise cofactor spacing and orientation. |

| Unnatural Amino Acids (e.g., 4-fluorotryptophan, p-cyanophenylalanine) | Probes electronic coupling via altered electronic properties or introduces novel redox potentials at specific sites. |

| Photo-triggerable Redox Donors (e.g., [Re(I)(CO)_3(dimine)]^+, Zn-substituted porphyrin) | Enables ultrafast, trigger-initiated ET for measuring kinetics in frozen or solution states. |

| Rigid Covalent Spacers (e.g., bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane, propargyl linkers) | Holds redox cofactors at fixed, well-defined distances and orientations within a protein cavity. |

| Paramagnetic NMR Tags (e.g., EDTA-Mn^{2+}, nitroxide spin labels) | Measures long-range distances (15-60 Å) via Pulsed-EPR (DEER) to validate D-A placement in solution. |

| Computational Suite (e.g., HARLEM, VOTCA for pathway analysis; Rosetta for design) | Predicts ET rates, identifies optimal pathways, and designs protein scaffolds for cofactor incorporation. |

Workflow for Engineering ET in Proteins

Marcus Theory Parameter Interplay

This whitepaper, framed within the broader thesis of applying Marcus theory to electron transfer (ET) in engineered proteins, explores the deliberate modification of the protein-solvent medium to control the two key parameters governing ET rates: the electronic coupling matrix element (HAB) and the reorganization energy (λ). According to Marcus theory, the ET rate constant (kET) is expressed as: kET = (4π²/ℎ) * HAB² * (4πλkBT)⁻¹/² * exp[-(ΔG° + λ)²/(4λkBT)] where ℎ is Planck's constant, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and ΔG° is the driving force. Tuning the protein matrix directly modulates HAB (through pathway connectivity) and λ (through dielectric and relaxation properties), enabling precise control over biological electron flow for applications in biocatalysis, biosensing, and bioenergy.

Core Principles: Medium Effects on Marcus Parameters

Modulating Electronic Coupling (HAB)

The electronic coupling between donor (D) and acceptor (A) depends exponentially on the distance and the nature of the intervening medium. The coupling through a protein matrix can be approximated by tunneling pathway models, where covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds, and through-space jumps contribute differently.

Key Strategy: Introducing non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) with enhanced orbital overlap (e.g., propargyltyrosine), or rigidifying the structure with cross-linkers, can create optimized tunneling pathways.

Engineering Reorganization Energy (λ)

λ represents the energy required to reorganize the nuclear coordinates of the reactant, product, and surrounding medium upon ET. It is composed of inner-sphere (λi, from donor/acceptor geometry changes) and outer-sphere (λs, from protein/solvent repolarization) components. λ = λi + λs

Key Strategy: Modifying the hydrophobicity, polarizability, and rigidity of the active site pocket or the secondary coordination sphere directly tunes λs. A less polar, more rigid environment typically lowers λ.

Table 1: Measured ET Parameters in Engineered Protein Systems

| Protein System / Modification | Donor-Acceptor Pair | Electronic Coupling, HAB (cm⁻¹) | Reorganization Energy, λ (eV) | ET Rate, kET (s⁻¹) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Rb. sphaeroides Reaction Center | (BChl)₂ → BPh | 24 ± 5 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | (3.0 ± 0.6) x 10¹¹ | [1] |

| Cyt c with native Fe-His linkage | Heme (Fe³⁺/²⁺) | -- | 0.75 | -- | [2] |

| Cyt c with Cys-Fe-His pathway (engineered) | Heme (Fe³⁺/²⁺) | 1.2 x 10⁻³ | 0.68 | 2.4 x 10⁴ | [2] |

| Azurin (WT) | Cu⁺/²⁺ | ~0.5 | 0.7 | 30 | [3] |

| Azurin, Asn47→Phe (hydrophobic cavity) | Cu⁺/²⁺ | ~0.5 | 0.5 | 300 | [3] |

| Maquette with packed Phe/Leu core | ZnP → Fe³⁺Heme | ~0.01 | 0.3 | 1.6 x 10⁶ | [4] |

| Maquette with polar Thr/Ser core | ZnP → Fe³⁺Heme | ~0.01 | 0.8 | 1.6 x 10⁵ | [4] |

Table 2: Common Matrix Modifications and Their Effects

| Modification Type | Example Reagents/Techniques | Primary Effect on HAB | Primary Effect on λ | Net Impact on kET |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Packing | ncAAs (e.g., 5,5,5-Trifluoroleucine), Phe, Leu, Ile | Minimal Increase | Decrease (λs↓) | Increase |

| Polar Introduction | ncAAs (e.g., p-Nitro-Phe), Ser, Thr, Glu | Minimal Decrease | Increase (λs↑) | Decrease |

| Pathway Rigidification | Disulfide cross-linking, Bipyridine incorporation | Increase (reduced dynamic disorder) | Decrease (restricted motion) | Increase |

| π-System Extension | Propargyltyrosine, 2-Naphthylalanine | Increase (enhanced tunneling) | Variable | Increase |

| Solvent Viscosity | Glycerol, Sucrose, Ficoll | Minimal (possible decrease) | Increase (λs↑) | Decrease |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Site-Specific Incorporation of ncAAs for λ Control

Aim: To lower outer-sphere reorganization energy by creating a hydrophobic, rigid active site. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Gene Design: Mutate target codon(s) in the protein gene to an amber (TAG) stop codon using site-directed mutagenesis.

- Orthogonal System Preparation: Co-transform E. coli with two plasmids: (a) pEVOL-pCNF (or other corresponding pEVOL vector) encoding the orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS)/tRNACUA pair specific for the desired ncAA (e.g., 5,5,5-Trifluoroleucine), and (b) your target protein gene under an inducible promoter (e.g., pET vector with T7 promoter).

- Expression & Incorporation: Grow cells in defined medium to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6). Induce with 0.02% L-arabinose (to express the aaRS/tRNA pair) and 1 mM IPTG (to express the target protein). Simultaneously add the ncAA (2-10 mM final concentration) to the culture.

- Purification: Harvest cells, lyse, and purify the full-length protein containing the ncAA via affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag). Confirm incorporation and site-specificity via intact mass spectrometry.

- Electrochemical Analysis: Use protein film voltammetry (PFV) on a pyrolytic graphite edge electrode. From the width of the non-Faradaic current in a cyclic voltammogram, calculate λ using the equation: λ = FΔEwidth / (4√(RTln2)), where F is Faraday's constant, R is the gas constant, and ΔEwidth is the peak-to-peak separation.

Protocol: Laser Flash Photolysis to MeasurekETand Derive Parameters

Aim: To determine the ET rate between a photo-excited donor (e.g., Ru(II)-polypyridyl complex) and a protein-bound acceptor (e.g., heme Fe³⁺). Method:

- Protein Labeling: Covalently attach a photosensitizer (e.g., Ru(bpy)₂(im)(His)⁺) to a surface His residue on the target protein via coordination.

- Sample Preparation: In an anaerobic glovebox, prepare the protein sample (~50 µM) in degassed buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.0) with 5 mM sodium ascorbate as a sacrificial donor for the Ru complex. Seal in a quartz cuvette.

- Laser Excitation: Use a pulsed Nd:YAG laser (e.g., 532 nm, 5 ns pulse) to excite the Ru complex to its metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) state (Ru²⁺).

- Kinetics Monitoring: Monitor the transient absorption decay of the Ru²⁺ at 460 nm and/or the formation/decay of the reduced acceptor (e.g., heme Fe²⁺ at 430 nm for cytochrome c) using a fast photodiode or CCD spectrometer.

- Data Analysis: Fit the decay of Ru²⁺ or rise of acceptor reduction to a single or multi-exponential model to extract the observed rate constant (kobs).

- Parameter Extraction: For a series of driving forces (-ΔG°), obtained by varying the acceptor (e.g., using different heme proteins or applied potential), fit the data to the Marcus equation to extract the intrinsic λ and HAB. Plot ln(kET) vs. -(ΔG° + λ)²/(4λkBT) for the inverted region.

Diagrams

Title: Medium Modification Controls Marcus Theory Parameters

Title: Decision Workflow for Tuning Protein Electron Transfer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Protein Matrix Tuning Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Tuning | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Amber Suppressor tRNA/aaRS Plasmids | Enables site-specific incorporation of ncAAs. | pEVOL vectors (Addgene), specific for pCNF, pAcF, etc. |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs) | Directly modifies side-chain properties (polarity, size, polarizability) in the protein matrix. | 5,5,5-Trifluoroleucine (Sigma), propargyltyrosine (Chem-Impex), p-Nitro-Phenylalanine (Alamanda). |

| Cross-linking Reagents | Rigidifies protein structure to reduce dynamic disorder and tune coupling/pathways. | Bismaleimidoethane (BMOE, Thermo), DTSSP (Lomant's reagent, spacer arm 12Å). |

| Photo-redox Sensitizers | Acts as a well-characterized, tunable electron donor for flash photolysis kinetics. | Ru(bpy)₂(im)(His)⁺ (synthesized in-house or from complexes like [Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺). |

| Anaerobic Experiment Kits | Essential for studying ET without interference from O₂. | Coy Lab Glovebox, Pierce Anaerobic Chamber, AnaeroPack sachets. |

| High-Viscosity Media | Tunes outer-sphere λ by modulating solvent relaxation dynamics. | Ultrapure glycerol, sucrose, Ficoll PM-400. |

| Protein Film Voltammetry Electrodes | For direct electrochemical measurement of reorganization energy. | Basal plane pyrolytic graphite (PG) electrode (e.g., from Momentive). |

| Fast Kinetics Spectrometer | Measures ET rates on picosecond to microsecond timescales. | Edinburgh Instruments LP980 with Nd:YAG laser, or similar transient absorption system. |

The rational design of electron transfer (ET) pathways within de novo protein scaffolds represents a frontier in synthetic biology and bioenergetics. This pursuit is fundamentally governed by Marcus theory, which provides the quantitative framework relating the ET rate ((k{ET})) to the driving force ((-\Delta G^\circ)), reorganization energy ((\lambda)), and electronic coupling ((H{AB})):

[ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |H{AB}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kBT}} \exp\left[-\frac{(\Delta G^\circ + \lambda)^2}{4\lambda kBT}\right] ]

Within engineered proteins, the challenge is to precisely control these parameters by orchestrating the spatial arrangement of redox cofactors (e.g., hemes, Fe-S clusters, flavins) within an otherwise non-conductive polypeptide matrix. This case study details the design principles, experimental validation, and quantitative analysis of a high-efficiency ET pathway built from a de novo α-helical bundle scaffold.

Core Design Principles from Marcus Theory

Successful pathway design requires optimization of three Marcus parameters:

- Electronic Coupling ((H_{AB})): Achieved through strategic placement of redox cofactors at distances typically <14 Å, with optimal through-bond or through-space pathways provided by protein secondary structure (e.g., helical turns).

- Reorganization Energy ((\lambda)): Minimized by creating a hydrophobic, rigid protein interior that reduces dielectric relaxation and solvent reorganization upon cofactor oxidation/reduction.

- Driving Force ((-\Delta G^\circ)): Tuned by selecting cofactor pairs with appropriate reduction potentials, often modulated by the electrostatic environment (e.g., neighboring residues, H-bonding networks).

Experimental Protocol: Construct Assembly & Characterization

The following protocol outlines the key steps for creating and analyzing a model di-heme de novo protein.

3.1. De Novo Scaffold Selection and Cofactor Integration

- Scaffold: A stable four-helix bundle (e.g., Alpha3D variant) provides a predictable, tunable framework.

- Gene Synthesis: The protein sequence is codon-optimized and synthesized, incorporating axial ligand residues (e.g., Histidine for heme) at precisely defined positions within the bundle core.

- Expression & Purification: The gene is cloned into a pET vector, expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells in TB media. Protein is purified via immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) exploiting a C-terminal hexahistidine tag.

- Heme Incorporation: Heme (Fe(III)-protoporphyrin IX) is incorporated in vitro into the apo-protein under reducing conditions (5 mM DTT) and purified by size exclusion chromatography.

3.2. Spectroscopic & Kinetic Characterization

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Confirms heme incorporation via the characteristic Soret (~410 nm) and Q-band features. Redox titrations monitor shifts for potential determination.

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Protein is adsorbed on a pyrolytic graphite edge electrode. CV in a sealed anaerobic cell with a Ag/AgCl reference electrode determines formal reduction potentials ((E^\circ)').

- Flash-Quench Laser Kinetics: The photo-induced ET rate is measured. A ruthenium photosensitizer ([Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺) is covalently attached to a surface cysteine. A flash laser (460 nm) excites the Ru complex, which is quenched by an external acceptor (e.g., [Co(NH₃)₅Cl]²⁺), generating Ru³⁺. Intra-protein ET from the nearby heme to Ru³⁺ is monitored by transient absorption decay at the heme Soret band.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Engineered Di-Heme Electron Transfer Proteins

| Protein Variant | Cofactor Distance (Å) | ΔE°' (mV) | λ (eV) | HAB (cm⁻¹) | kET (s⁻¹) | Driving Force Optimized? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bundle-HH1 | 12.3 | 85 | 0.75 | 0.12 | 1.2 x 10⁶ | No |

| Bundle-HH2 | 10.8 | 120 | 0.68 | 0.85 | 4.7 x 10⁷ | Yes |

| Bundle-HH3 | 14.1 | 80 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 3.8 x 10⁴ | No |

| Natural Cyt c | 14.2 | ~100 | 0.70-0.80 | ~0.1 | ~1 x 10⁴ | N/A |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| pET-28a(+) Vector | High-level expression in E. coli with His-tag for purification. | Provides T7 promoter and kanamycin resistance. |

| Fe(III)-Protoporphyrin IX | Heme cofactor for incorporation into apo-proteins. | Must be stored dark, anhydrous; use fresh stock in DMSO. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) | Non-thiol, stable reducing agent for maintaining anaerobic conditions. | Preferred over DTT for long-term stability. |

| [Ru(bpy)₂(imidazole)(His)] Complex | Site-specific photooxidant for flash-quench kinetics. | Synthesized to label surface His-tag or cysteine. |

| Anaerobic Glove Box (N₂ atmosphere) | Maintains an oxygen-free environment for redox chemistry. | O₂ levels must be <1 ppm for potentiometric titrations. |

| Sephadex G-25 / PD-10 Desalting Columns | Rapid buffer exchange and removal of excess heme/salts. | Fast, gravity-driven method to preserve protein activity. |

Pathway Visualization & Workflow

Diagram 1: Protein ET Pathway Design Workflow

Diagram 2: Marcus Theory to Design Parameter Mapping

Diagnosing and Optimizing Electron Transfer: A Marcus Theory Toolkit

Within the framework of Marcus theory applied to engineered proteins, electron transfer (ET) kinetics are governed by the interplay of three fundamental parameters: the electronic coupling matrix element (HAB), the reorganization energy (λ), and the driving force (-ΔG°). The rate constant is expressed as: kET = (4π²/ℎ) * HAB² * (4πλkBT)⁻¹/² * exp[-(λ + ΔG°)²/(4λkBT)]

The "bottleneck" for a given system is the parameter that most severely limits the achievable ET rate. Identifying it is crucial for rational protein design in bioelectronics, biosensors, and enzymatic catalysis. This guide provides a contemporary, technical analysis for distinguishing between these limiting factors.

Core Parameters & Quantitative Benchmarks

The following table summarizes typical quantitative ranges for these parameters in engineered protein systems, based on current literature.

Table 1: Marcus Theory Parameters in Engineered Protein Electron Transfer

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range in Engineered Proteins | Role in Marcus Theory | Experimental Method (Primary) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Coupling | HAB | 10⁻⁴ – 10² cm⁻¹ | Governs the probability of electron tunneling at the transition state. Determines the adiabatic/non-adiabatic regime. | Donor-Acceptor Distance Dependence (ET rate vs. distance), Tunnel coupling calculations. |

| Reorganization Energy | λ | 0.3 – 2.0 eV | Energy required to reorganize nuclear coordinates (solvent & protein) upon ET. Includes inner-sphere (λi) and outer-sphere (λs) components. | Analysis of Driving Force Dependence (Marcus Plot), Stark Spectroscopy, Computational MD/DFT. |

| Driving Force | -ΔG° | 0 – 1.5 eV (tunable) | The negative of the standard free energy change for the ET reaction. | Electrochemistry (CV), Redox Potentiometry, Photochemical Titration. |

| Optimal Driving Force | -ΔG°opt | Equal to λ | The driving force at which the ET rate is maximal (in the normal Marcus region). | Derived from the peak of a parabolic Marcus plot. |

Distinguishing the Limiting Factor: Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Diagnosing Coupling-Limited Transfer

Objective: Determine if ET is non-adiabatic and limited by weak electronic coupling (HAB). Rationale: In the non-adiabatic regime, kET ∝ HAB². HAB decays exponentially with donor-acceptor distance (r): HAB² ∝ exp(-βr).

- Sample Preparation: Engineer a series of protein constructs with a rigid, well-defined structural bridge (e.g., α-helix, β-sheet) between a chosen donor (D) and acceptor (A) pair. Systematically vary the D-A distance (r) by inserting or removing a fixed number of residues/mediators.

- Kinetic Measurement: For each construct, measure the ET rate (kET) using laser-induced pulsed spectroscopy (e.g., flash-quench for photoinitiated ET) or electrochemical methods (for immobilized proteins).

- Data Analysis: Plot ln(kET) vs. r. A linear relationship confirms the non-adiabatic, coupling-limited regime. The slope yields the attenuation factor β (Å⁻¹). A high β (>1.0 Å⁻¹) indicates strong distance dependence and coupling limitation.

Protocol B: Diagnosing Reorganization-Limited Transfer

Objective: Determine if ET is in the Marcus inverted region or has an unusually high λ. Rationale: The dependence of ln(kET) on driving force (-ΔG°) is parabolic: ln(kET) ∝ -(λ + ΔG°)²/(4λkBT).

- Sample Preparation: Engineer a series of proteins with identical D-A distances and coupling pathways, but with systematically tuned redox potentials (and thus ΔG°). This is achieved via point mutations near the redox cofactor (e.g., heme ligation, hydrogen bonding network) or by using different metallo-/flavoprotein variants.

- Kinetic & Thermodynamic Measurement: For each variant, measure both the ET rate (kET) and the precise driving force (-ΔG°). -ΔG° can be determined from the difference in midpoint potentials (Em) measured by protein film voltammetry or spectroelectrochemistry.

- Data Analysis: Construct a "Marcus plot" of ln(kET) vs. -ΔG°. A parabolic fit yields the reorganization energy λ (from the peak position, -ΔG°opt = λ) and the electronic coupling (from the peak height). If λ is large (>1 eV), the reaction is reorganization-heavy. If the data points fall on the inverted region (-ΔG° > λ), the reaction is inherently limited by the nuclear reorganization penalty.

Protocol C: Diagnosing Driving Force-Limited Transfer

Objective: Determine if ET is in the normal Marcus region with suboptimal -ΔG°. Rationale: In the normal region (-ΔG° < λ), the rate increases exponentially with driving force.

- Sample Preparation: Similar to Protocol B, create variants with tuned -ΔG° but within a smaller range expected to be in the normal region.

- Measurement: As in Protocol B.

- Data Analysis: On the Marcus plot, if the measured rates for a system of interest fall on the steeply rising left slope of the parabola, the reaction is driving force-limited. Increasing -ΔG° (e.g., by raising the donor potential or lowering the acceptor potential) will significantly accelerate ET. This is confirmed if λ, determined from a full parabola (Protocol B), is significantly larger than the operational -ΔG°.

Visualizing the Diagnostic Framework

Diagram 1: Experimental Diagnostic Flowchart

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Materials for Bottleneck Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function & Relevance | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Protein Constructs | The core testbed. Requires a stable protein scaffold (e.g., Cytochrome c, Azurin, Photosynthetic Reaction Center mutants) with precisely defined donor/acceptor sites and a mutable pathway. | His-tagged for immobilization; Cysteine variants for specific labeling. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | To systematically alter residues for tuning distance, coupling pathway, or redox potential. | Commercial kits (e.g., NEB Q5) for high-fidelity PCR-based mutagenesis. |

| Non-Natural Amino Acids/Redox Cofactors | To insert spectroscopic probes or tune redox potentials beyond natural limits. | e.g., 4-Fluorotryptophan (19F NMR probe), modified hemes or Ru(bpy)₂(im) complexes for potential tuning. |

| Ultrafast Laser System | For initiating and measuring photoinduced ET kinetics on picosecond-nanosecond timescales. | Ti:Sapphire oscillator/amplifier with pump-probe or transient absorption detection. |

| Protein Film Voltammetry (PFV) Setup | For direct electrochemical measurement of ET rates and redox potentials of proteins immobilized on an electrode. | Au or pyrolytic graphite working electrode; low-temperature-capable cell for studying non-adiabatic ET. |

| Spectroelectrochemical Cell | To correlate spectroscopic changes (UV-Vis, EPR) with applied potential for precise determination of midpoint potentials (Em). | Optically transparent thin-layer electrode (OTTLE) cell. |

| Quantum Chemistry/MD Software | To compute electronic coupling (HAB) via pathways or DFT, and reorganization energy (λ) via molecular dynamics. | e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, VMD/NAMD with QM/MM modules. |

This whitepaper details optimization strategies for modulating electron transfer (ET) kinetics in engineered proteins, framed within the context of Marcus theory. Marcus theory describes ET rates as a function of the driving force (∆G°), the reorganization energy (λ), and the electronic coupling (HDA) between donor (D) and acceptor (A). The rate constant kET is given by:

[ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |H{DA}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kBT}} \exp\left[-\frac{(\Delta G^\circ + \lambda)^2}{4\lambda kBT}\right] ]

Protein engineering aims to fine-tune these parameters—particularly λ and HDA—through mutagenesis to optimize ET for applications in biocatalysis, biosensors, and bioenergy.

Key Parameters and Mutagenesis Targets

Table 1: Marcus Theory Parameters and Corresponding Mutagenesis Strategies

| Parameter | Physical Meaning | Primary Tuning Strategy via Mutagenesis | Expected Impact on kET | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆G° | Driving Force (Energy Difference) | Altering redox potentials of cofactors or amino acids (e.g., heme, Fe-S clusters, Tyr, Trp). | Modulates the exponent; maximum rate at -∆G° = λ. | ||

| λ | Reorganization Energy (Energy to reorganize solvation & nuclei) | Modifying protein rigidity & solvent exposure around D/A. Increasing hydrophobicity/rigidity decreases λ. | Lower λ increases rate, sharpens driving force dependence. | ||

| HDA | Electronic Coupling (Overlap of D/A wavefunctions) | Optimizing tunneling pathway: distance, spacing, and nature (covalent vs. H-bond vs. van der Waals) of intervening atoms. | Rate proportional to | HDA | 2; sensitive to pathway structure. |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing ET Kinetics

Laser-Induced Pulse Radiolysis for Direct Rate Measurement

Objective: Measure bimolecular or intramolecular ET rate constants. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Engineer and purify protein with distinct D and A sites (e.g., Ru-modified heme protein). Deoxygenate buffer.

- Radiolysis: Use a pulsed electron accelerator or laser to generate a burst of hydrated electrons (eaq-) or specific radicals (e.g., CO2•-).

- Selective Reduction: Radicals rapidly reduce one site (e.g., Ru3+ to Ru2+).

- Kinetic Tracing: Monitor time-resolved absorption changes at wavelengths specific to the other site (e.g., heme Soret band) using a spectrophotometer.

- Data Analysis: Fit the absorbance change to a single-exponential rise/decay to obtain the observed rate constant kobs. Plot kobs vs. donor-acceptor distance to analyze tunneling decay.

Protein Film Electrochemistry (PFE) for Driving Force and Reorganization Energy

Objective: Determine ∆G° and λ by measuring ET rate as a function of applied potential. Protocol:

- Film Formation: Adsorb or covalently attach engineered redox protein onto a polished Au or graphite electrode.

- Voltage Sweep: Perform cyclic voltammetry in an anaerobic cell. Use a potentiostat to sweep voltage across the protein's redox potential.

- Non-Turnover Analysis: In the absence of substrate, the faradaic current is proportional to the ET rate between electrode and protein.

- Analysis: Fit the potential dependence of the current using the Marcus-DOS model. The width of the sigmoidal current-potential curve provides λ, while the midpoint provides formal potential (E°), related to ∆G°.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Title: Mutagenesis Strategies Targeting Marcus Theory Parameters

Title: Experimental Workflow for Optimizing Electron Transfer

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for ET Protein Engineering Studies

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| QuikChange/Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces precise amino acid changes into plasmid DNA to test specific mutations. |

| E. coli Expression System (e.g., BL21(DE3)) | Robust, high-yield production of engineered (often metallo)proteins. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resin (Ni-NTA) | Purifies His-tagged recombinant proteins efficiently for kinetic studies. |

| Anaerobic Chamber (Glove Box) | Allows manipulation of oxygen-sensitive proteins and redox cofactors without degradation. |

| Stopped-Flow or Laser Flash Photolysis System | Measures rapid ET kinetics (ns-ms) by triggering electron injection with light or chemical mixing. |

| Potentiostat & Electrochemical Cell | For protein film electrochemistry to determine redox potentials and reorganization energies. |

| Ruthenium Photooxidants (e.g., Ru(bpy)₃²⁺) | Covalently attachable, light-triggered electron donors for initiating intraprotein ET. |

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O) | Used in kinetic isotope effect studies to probe proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) pathways. |

| Continuous-Wave EPR Spectroscopy | Detects and characterizes paramagnetic intermediates (radicals, metal centers) formed during ET. |

This whitepaper addresses a pivotal challenge in the application of Marcus theory to engineered protein systems: the kinetic limitation imposed by the "inverted region." According to Marcus theory, the rate of electron transfer (ET) decreases when the driving force (‑ΔG°) becomes excessively large, a phenomenon central to understanding and optimizing biological ET pathways. Within the broader thesis of applying Marcus theory to protein engineering, this guide details modern experimental and computational strategies to bypass this barrier, enabling the design of proteins with ultrafast, efficient, and controlled ET for applications in biosensing, synthetic biology, and drug development.

Core Concepts: Marcus Theory and the Inverted Region

Marcus theory describes the ET rate constant (kET) as: kET = (2π/ħ) |HAB|² (4πλkBT)⁻¹/² exp[‑(ΔG° + λ)²/4λkBT] where HAB is the electronic coupling, λ is the reorganization energy, and ΔG° is the driving force. The "inverted region" occurs when ‑ΔG° > λ, causing kET to decline.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Marcus Theory for Protein Engineering

| Parameter | Symbol | Role in ET Kinetics | Typical Range in Proteins | Engineering Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | ‑ΔG° | Free energy change of reaction | 0 to ~2.0 eV | Moderate to avoid deep inversion |

| Reorganization Energy | λ | Energy for nuclear rearrangement | 0.5 - 1.5 eV | Minimize |

| Electronic Coupling | HAB | Donor-Acceptor orbital overlap | 1 - 100 cm⁻¹ | Maximize & control pathway |

| ET Rate Constant | kET | Measured rate | 10⁰ - 10¹² s⁻¹ | Optimize for application |

Engineering Strategies to Overcome the Inverted Region

Strategy 1: Minimizing Reorganization Energy (λ) The kinetic penalty of the inverted region is mitigated by reducing λ. This involves engineering the protein matrix to rigidify the donor, acceptor, and intervening medium.

- Experimental Protocol: Site-Directed Mutagenesis for Rigidification

- Target Selection: Using computational docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, identify flexible residues in the ET pathway between redox cofactors (e.g., hemes, Fe-S clusters, flavins).

- Mutagenesis Design: Design mutations to introduce proline residues or bulky, non-polar side chains (e.g., Trp, Phe) to restrict side-chain and backbone mobility. Target hydrogen-bond networks to stabilize water molecules.

- Gene Construction: Perform PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis on the plasmid encoding the target protein. Verify sequences by Sanger sequencing.

- Protein Expression & Purification: Express variant proteins in E. coli (or relevant host). Purify via affinity (His-tag), ion-exchange, and size-exclusion chromatography.

- Measurement of λ: Determine λ via variable-temperature electrochemical measurements (e.g., protein film voltammetry) or analysis of ET rates vs. driving force using a series of donor/acceptor pairs. λ can be extracted from the curvature of the Marcus plot.

Strategy 2: Modulating Electronic Coupling (HAB) Enhancing HAB can boost kET sufficiently to overcome the inverted region's exponential decay.

- Experimental Protocol: Tunneling Pathway Engineering

- Pathway Calculation: Use computational tools like HARLEM or PATHWAYS to identify optimal through-bond tunneling pathways between cofactors.

- Covalent Linker Design: For de novo designed proteins or systems, synthetically incorporate conjugated molecular bridges (e.g., phenylacetylene, oligoproline with π-stacking) between donors and acceptors.

- Non-Natural Amino Acid Incorporation: Utilize amber codon suppression to introduce residues with enhanced orbital overlap (e.g., selenocysteine, side chains with conjugated systems) at key positions in the pathway.

- Coupling Measurement: Quantify HAB via analysis of electronic absorption bands (intervalence charge transfer), temperature-independent analysis of ET rates, or electronic structure calculations (DFT) on model systems.

Strategy 3: Multi-Step Electron Hopping Bypass the single-step inverted region by breaking the reaction into a series of smaller, more favorable ET steps via inserted redox-active intermediates.

- Experimental Protocol: Introducing Artificial Redox Intermediates

- Intermediate Selection: Choose a redox mediator compatible with the protein environment (e.g., flavin mononucleotide (FMN), ruthenium bipyridyl complexes, tyrosine/tryptophan radicals).

- Site-Specific Incorporation: Genetically encode a binding motif (e.g., LOV domain for FMN) or use bioconjugation chemistry (e.g., cysteine-maleimide) to covalently attach the mediator at a designed site along the putative ET path.

- Kinetic Characterization: Use pulsed laser flash photolysis to initiate ET from a photoexcited donor (e.g., Zn-porphyrin) and monitor the transient absorption of intermediates to establish the hopping sequence and individual step rates.

Diagram Title: Multi-Step Hopping Bypasses Inverted Region Kinetic Trap

Case Study: Engineered Cytochrome P450 for Catalysis

Objective: Enhance the rate of ET from the reductase partner (POR) to the heme in P450 enzymes, a step often limited by the inverted region due to a highly exergonic initial step.

Engineered Workflow:

Diagram Title: P450 ET Engineering and Screening Workflow

Key Measurements & Results: Table 2: Example Data from Engineered P450 Variants

| Variant | Mutation Target | λ (eV) | Relative kET (POR→Heme) | Catalytic Turnover (min⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | N/A | 1.05 | 1.0 | 45 |

| Variant A | Proximal H-Bond Network | 0.82 | 3.2 | 112 |

| Variant B | Aromatic Residue Insertion | N/A (↑HAB) | 5.1 | 98 |

| Variant C | Surface Ru-Complex Graft | Multi-Step | 8.7 (overall) | 205 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for ET Protein Engineering

| Item / Reagent | Function & Application | Example Vendor/Code |

|---|---|---|

| QuikChange II XL | High-efficiency site-directed mutagenesis kit for constructing point mutations. | Agilent, 200521 |

| Non-Natural Amino Acids | Incorporation of spectroscopic probes or redox mediators via genetic code expansion. | MilliporeSigma (e.g., p-Azido-L-phenylalanine) |

| Ruthenium Labeling Reagents | Site-specific conjugation of photo-redox active Ru(bpy)₃²⁺ complexes to engineered cysteines. | TCI Chemicals (e.g., Ru(bpy)₂(maleimide) |

| DEER/NMR Spin Labels | Probes (MTSSL, Gd³⁺ chelates) for measuring distances/conformational dynamics related to ET. | Toronto Research Chemicals |

| Protein Film Electrode | Gold or pyrolytic graphite electrode for direct electrochemistry to measure E° and λ. | BASi, C-1A Cell |

| Stopped-Flow System | Rapid mixing (<1 ms) to measure fast ET kinetics via absorbance/fluorescence. | Applied Photophysics, SX20 |

| Transient Absorption Spectrometer | Laser flash photolysis system to measure photoinduced ET on ns-μs timescales. | Edinburgh Instruments, LP980 |

The application of Marcus theory to electron transfer (ET) in engineered proteins provides a foundational framework for understanding the relationship between reaction free energy, reorganization energy, and electronic coupling. A critical, often oversimplified, assumption in classical Marcus theory is that the protein scaffold exists in a static, equilibrium configuration. In reality, proteins exhibit conformational dynamics across a wide range of timescales, from fast side-chain rotations to slow domain motions. This dynamic disorder—the time-dependent fluctuation of parameters like donor-acceptor distances, electronic coupling, and reorganization energy—can significantly modulate measured electron transfer rates. This whitepaper details how accounting for these motions refines the Marcus model, moving from a single, averaged rate constant to a distribution or time-dependent function, essential for accurate interpretation of experiments in bioengineering and drug development targeting redox-active proteins.

The Theoretical Framework: From Static to Dynamic Marcus Theory

Classical Marcus theory expresses the non-adiabatic ET rate constant, kET, as: kET = (2π/ħ) |HDA|2 (4πλkBT)-1/2 exp[-(ΔG° + λ)2 / 4λkBT]

Where HDA is the electronic coupling, λ is the reorganization energy, and ΔG° is the reaction free energy. Dynamic disorder requires treating one or more of these parameters as stochastic variables.

Modeling Dynamic Disorder

Two primary approaches are used:

- Static Disorder: Assumes an ensemble of static conformations with a Gaussian distribution of parameters (e.g., coupling or reorganization energy). The observed rate is an average over this distribution.

- Dynamic Disorder: Explicitly models parameter fluctuations over time, often as a diffusive or two-state process on the reaction free energy surface. This is crucial when fluctuation timescales are comparable to or slower than the ET event itself.

Key Quantitative Relationships

The impact of dynamics is characterized by the timescale of fluctuations (τc) relative to the average ET rate (<kET>).

- Fast Fluctuations (τc << 1/<kET>): The system samples all configurations rapidly; the classical averaged Marcus rate holds.

- Slow Fluctuations (τc >> 1/<kET>): Each measurement probes a sub-ensemble, leading to kinetic dispersion and non-exponential decay kinetics.

- Comparable Timescales (τc ≈ 1/<kET>): Requires explicit dynamical models, such as coupled Marcus-Smoluchowski equations.

Table 1: Timescales of Protein Motions and Their Impact on ET Parameters

| Motion Type | Approximate Timescale | Primary ET Parameter Affected | Experimental Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side-Chain Rotamer Flips | 10 ps - 10 ns | Electronic Coupling (HDA) | MD Simulation, NMR |