Cysteine Redox Switches: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting in Human Disease

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of the redox regulation of protein cysteine residues, a dynamic post-translational mechanism central to cellular signaling and homeostasis.

Cysteine Redox Switches: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Targeting in Human Disease

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive synthesis of the redox regulation of protein cysteine residues, a dynamic post-translational mechanism central to cellular signaling and homeostasis. We explore the foundational chemistry of reactive cysteines and the spectrum of their oxidative modifications, such as S-sulfenylation and S-glutathionylation. The content details cutting-edge methodological advances in redox proteomics and computational modeling for profiling the cysteine redoxome. Furthermore, it addresses key challenges in troubleshooting pathway specificity and discusses the validation of redox-sensitive proteins as promising targets for therapeutic intervention in conditions ranging from liver disease to aging and cancer, offering a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals in the biomedical sciences.

The Chemistry and Biology of Cysteine Redox Switches

Within the intricate landscape of cellular signaling, the unique chemistry of the cysteine thiol group enables proteins to sense and transduce changes in cellular redox status. Cysteine is one of the least abundant amino acids, yet it is frequently found as a highly conserved residue within functional sites in proteins, exhibiting extreme patterns of conservation indicative of strong selective pressure [1]. This conservation stems from the singular properties of the sulfur atom in its thiol (-SH) functional group, which can undergo a remarkable array of reversible chemical modifications in response to reactive oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur species (ROS/RNS/RSS) [2] [3]. These modifications allow specific cysteine residues to act as "redox switches," controlling critical biological processes including gene expression, enzyme activity, and cellular adaptation to stress [2] [4].

The redox-sensing capability of cysteine is not merely a chemical curiosity but a fundamental mechanism of physiological regulation. Cells continually monitor their environment and adapt to changing surroundings by coordinated changes in gene expression and metabolic pathways, with cysteine thiols serving as key environmental sensors [2]. This whitepaper examines the chemical basis for cysteine's unique reactivity, the biological mechanisms of thiol-based redox switching, experimental approaches for studying these processes, and the emerging therapeutic implications for targeting redox-sensitive pathways in human disease.

Fundamental Chemical Properties of Cysteine Thiols

The Electronic Basis of Sulfur Reactivity

The exceptional reactivity of cysteine in redox sensing originates from the electronic configuration of sulfur. Unlike methionine, which contains a less reactive thioether, cysteine features a ionizable thiol group that can undergo deprotonation to form a negatively charged thiolate anion (RS-) under physiological conditions [1]. This thiolate form is significantly more nucleophilic and reactive than its protonated counterpart, enabling attacks on electrophilic centers in oxidizing molecules.

The sulfur atom in cysteine is highly polarizable, meaning its electron cloud can be easily distorted in response to environmental influences. This polarizability enhances the ability of cysteine thiols to form transition states during redox reactions, stabilizing reaction intermediates and lowering activation energies [1] [5]. Furthermore, the sulfur atom can access multiple oxidation states, from the reduced thiol (-2) to various oxidized forms including disulfides (-1), sulfenic acids (0), sulfinic acids (+2), and sulfonic acids (+4), providing a rich chemical repertoire for biological signaling [2] [1].

Environmental Tuning of Cysteine Reactivity

The protein microenvironment profoundly influences cysteine reactivity through several mechanisms:

pKa Modulation: The protonation state of a cysteine thiol is governed by its acid dissociation constant (pKa). While typical thiol pKa values range from 8-9, protein environments can significantly lower this value through stabilization of the thiolate anion [1]. Strategic positioning near basic residues (histidine, arginine, lysine) or within helix dipoles creates electrostatic environments that favor deprotonation, increasing the concentration of the reactive thiolate species at physiological pH [1]. For example, in peroxiredoxins, hydrogen-bonding networks lower the pKa of the active site cysteine and simultaneously activate incoming peroxide substrates, resulting in reaction rates with hydrogen peroxide as high as 10ⷠ– 10⸠Mâ»Â¹ sâ»Â¹ [1].

Solvent Accessibility and Polarity: Despite classification in some hydrophobicity scales as a hydrophobic residue, cysteine exhibits polarity similar to serine [1]. Bioinformatics analyses reveal that cysteine residues show extreme conservation patterns, with high conservation in functional sites but poor conservation in solvent-exposed surfaces, reflecting evolutionary pressure to minimize unpaired surface cysteines that might undergo non-specific oxidation [1]. This selective pressure results in cysteine being both one of the most conserved and most degenerate amino acids, depending on its functional context.

Table 1: Factors Influencing Cysteine Reactivity in Proteins

| Factor | Effect on Reactivity | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Lowered pKa | Increases nucleophilicity by favoring thiolate formation | Active site cysteines in peroxiredoxins and phosphatases |

| Proximity to Basic Residues | Stabilizes thiolate anion through electrostatic interactions | Helix dipoles, histidine positioning |

| Hydrogen Bonding Networks | Activates both cysteine and substrate for reaction | Peroxiredoxin catalytic sites |

| Metal Coordination | Can dramatically alter redox potential | Iron-sulfur clusters, zinc fingers |

| Local Dielectric Constant | Influences proton transfer and charge stabilization | Hydrophobic active sites |

Cysteine Clustering: Bioinformatics studies reveal that cysteine residues frequently occur in clusters, particularly in proteins from organisms living in harsh environments [1]. This clustering facilitates disulfide bond formation and metal binding, creating specialized redox-active sites with enhanced sensitivity to oxidative changes. The spatial arrangement of multiple cysteine residues enables cooperative interactions that can fine-tune redox potential and create threshold responses to oxidative stimuli.

Biological Mechanisms of Thiol-Based Redox Sensing

The Spectrum of Cysteine Oxidative Modifications

Cysteine thiols undergo a diverse array of oxidative modifications that serve as molecular switches for redox signaling:

Disulfide Bond Formation: The formation of intra- or intermolecular disulfide bonds between cysteine residues represents a fundamental regulatory switch. This reversible modification can induce significant conformational changes that alter protein function, subcellular localization, or interaction partners [2] [4]. In bacteria, disulfide bond formation directly regulates transcription factors including OxyR, OhrR, and Spx, activating antioxidant gene expression in response to peroxide stress [2].

Sulfenic Acid Formation: The initial oxidation product of cysteine with hydrogen peroxide is cysteine sulfenic acid (-SOH). Although often transient, sulfenic acids can be stabilized in specific protein environments and serve both as sensory intermediates and regulatory modifications [2] [6]. For example, sulfenylation of Cys797 in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) enhances its tyrosine kinase activity, linking redox signaling to growth factor pathways [6].

S-Glutathionylation and S-Thiolation: Sulfenic acids can react with low molecular weight thiols such as glutathione to form mixed disulfides, a process known as S-glutathionylation [2]. This reversible modification can protect cysteine residues from irreversible overoxidation while simultaneously altering protein function. Similar S-thiolation reactions occur with other low molecular weight thiols, including mycothiol in Actinomycetes and bacillithiol in Firmicutes [2] [1].

S-Nitrosylation: Reactive nitrogen species can modify cysteine thiols to form S-nitrosothiols (R-SNO), providing a mechanism for nitric oxide-based signaling [2]. This modification occurs through multiple mechanisms, including reaction with nitric oxide (NO) or transnitrosation from low molecular weight S-nitrosothiols like GSNO.

Sulfenamide Formation: A more recently appreciated modification involves cyclization of sulfenic acid with a neighboring backbone amide nitrogen to form a cyclic sulfenamide [2]. This modification was first detected in structural studies of protein tyrosine phosphatases and has since been observed in bacterial redox sensors like Bacillus subtilis OhrR [2].

Table 2: Major Reversible Oxidative Modifications of Cysteine Thiols

| Modification | Chemical Structure | Representative Function | Reversibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfide | R-S-S-R' | Conformational switching in OxyR, Yap1 | Thioredoxin/Glutaredoxin |

| Sulfenic Acid | R-SOH | Redox sensing in EGFR, PTPs | Reduction or further oxidation |

| S-Glutathionylation | R-S-SG | Protection from overoxidation | Glutaredoxin |

| S-Nitrosylation | R-S-NO | NO signaling | Thioredoxin/Denitrosylases |

| Sulfenamide | Cyclic R-S-N | Stabilization of oxidized form | Reduction |

Structural Consequences of Thiol Oxidation

The biological impact of cysteine oxidation stems from the structural and functional changes induced in the modified protein. These changes can include:

Conformational Rearrangements: Disulfide bond formation can introduce covalent crosslinks that stabilize specific protein conformations. In the bacterial transcription factor OxyR, disulfide formation between Cys199 and Cys208 triggers a dramatic conformational change that activates transcription of antioxidant genes [2]. Similarly, oxidation of the yeast Yap1p transcription factor promotes structural changes that regulate its nuclear localization and DNA-binding activity [2].

Altered Protein-Protein Interactions: Redox modifications can create or disrupt interaction surfaces. For example, oxidation of the Nrf2-binding site on Keap1 disrupts the Nrf2-Keap1 complex, allowing Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus and activation of antioxidant response element (ARE)-mediated gene expression [2].

Modulated Catalytic Activity: Many enzymes contain redox-sensitive cysteine residues in their active sites. Protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) feature a nucleophilic cysteine that exists as a thiolate anion at neutral pH; oxidation to sulfenic acid inactivates these enzymes, thereby potentiating tyrosine phosphorylation signaling cascades [4] [6].

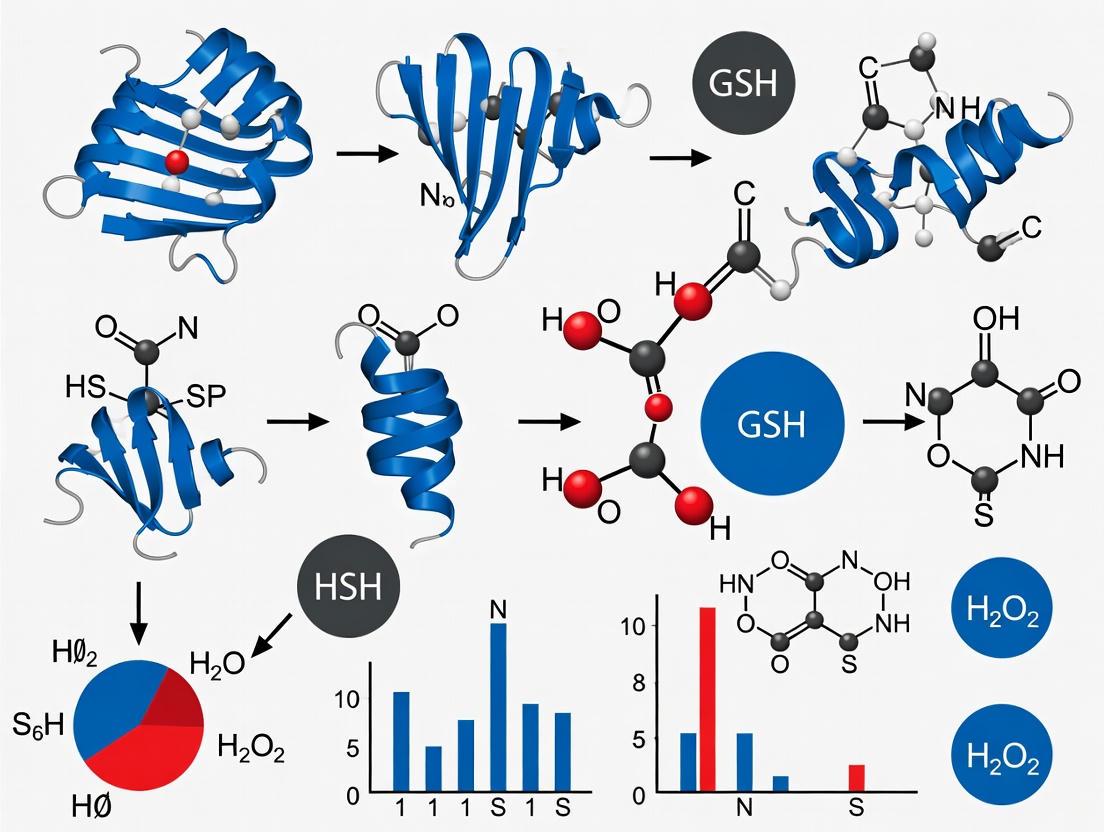

The following diagram illustrates the major oxidative pathways of cysteine thiols and their biological consequences in redox signaling:

Experimental Approaches for Studying Redox-Sensitive Cysteines

Proteomic Methods for Redox Profiling

Advanced proteomic techniques have enabled comprehensive mapping of cysteine redox states under physiological and pathological conditions. These methods generally rely on differentially labeling reduced and oxidized cysteines followed by quantification using mass spectrometry [7]. The iodoacetyl Tandem Mass Tag (iodoacetyl-TMT) approach allows multiplexed analysis of cysteine redox states across multiple samples, enabling comparisons between different experimental conditions, genetic backgrounds, or developmental stages [7].

A typical redox proteomics workflow involves:

- Cell lysis under controlled conditions to preserve native redox states

- Blocking free thiols with alkylating agents

- Reducing oxidized cysteines (disulfides, sulfenic acids)

- Labeling newly reduced thiols with isotopically distinct tags

- Protein digestion, peptide purification, and mass spectrometry analysis

- Computational determination of oxidized/reduced ratios for each cysteine

This approach was recently used to identify 151 proteins with altered redox states in lung fibroblasts from aged mice, with 69% of these changes reversible by Slc7a11 overexpression, highlighting connections between redox regulation and aging [7].

Site-Specific Manipulation of Redox Signaling

Traditional genetic and pharmacological approaches for studying cysteine function face significant limitations. Genetic mutation (e.g., cysteine-to-serine substitution) disrupts all cysteine functions, not just redox sensitivity, while exogenous oxidants lack specificity [6]. Emerging chemical biology strategies address these challenges through precise, site-specific manipulation:

Bioorthogonal Cleavage with Genetic Code Expansion: This approach enables site-specific incorporation of redox-sensitive modifications into proteins of interest. Photocaged cysteine sulfoxide analogs (e.g., DMNB-caged cysteine sulfoxide) can be incorporated as unnatural amino acids via genetic code expansion, allowing controlled generation of sulfenic acid upon UV irradiation [6]. This strategy enables precise temporal and spatial activation of redox signaling at specific sites.

Targeted Covalent Inhibitors (TCIs): Small molecules designed with moderately reactive warheads (e.g., nitroacetamide) can selectively block sulfenic acid modifications at specific target proteins without globally disrupting redox homeostasis [6]. These redox-based TCIs represent a promising therapeutic strategy for diseases involving dysregulated redox signaling.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying Cysteine Redox Biology

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thiol-Alkylating Agents | Iodoacetamide, N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) | Block free thiols to preserve redox states during analysis |

| Chemoselective Probes | Dimedone derivatives (DCP-Bio1, DYn-2) | Selective detection and enrichment of sulfenic acids |

| Redox Biosensors | roGFP, HyPer | Real-time monitoring of redox potential in living cells |

| Mass Tag Reagents | Iodoacetyl TMT, ICAT | Multiplexed quantification of cysteine oxidation states |

| Genetic Tools | CRISPR/Cas9, Redox-sensitive GFP constructs | Manipulation and monitoring of specific redox pathways |

| Low MW Thiol Analogs | Glutathione, Mycothiol, Bacillithiol | Study organism-specific thiol/disulfide systems |

Structural Biology Techniques

High-resolution structural methods including X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy have provided invaluable insights into the molecular mechanisms of thiol-based redox switches. Structures of redox-sensitive proteins in both reduced and oxidized states have revealed how disulfide formation or sulfenic acid modification triggers conformational changes that alter protein function [2] [4]. For example, structural studies of bacterial OhrR and SarZ have captured sulfenic acid intermediates and documented their structural consequences [2].

Biological Systems and Pathophysiological Implications

Prokaryotic Redox Sensing Systems

Bacteria employ sophisticated thiol-based redox sensors to adapt to oxidative stress encountered in their environments. Among the best-characterized systems is OxyR, a LysR-family transcription factor that senses hydrogen peroxide through disulfide bond formation between conserved cysteine residues [2]. Upon oxidation, OxyR activates expression of a regulon including catalases, peroxidases, and thiol-repair enzymes, coordinating the adaptive response to peroxide stress [2].

Other bacterial redox sensors include:

- OhrR/2-Cys: Repressors that sense organic hydroperoxides through cysteine oxidation

- Spx: A global regulator that controls disulfide stress responses in Gram-positive bacteria

- YodB: A MarR-family repressor that senses various electrophilic stressors

- CrtJ: A photosensor that uses cysteine oxidation to regulate photosynthesis genes

These systems demonstrate the remarkable versatility of cysteine chemistry in environmental sensing and transcriptional regulation [2].

Eukaryotic Redox Signaling in Health and Disease

In eukaryotes, thiol-based redox regulation impacts numerous physiological processes and disease states:

Aging and Longevity: Redox signaling through cysteine modifications has emerged as a key regulator of aging processes. Recent research demonstrates that ROS and hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) mediate lifespan extension in model organisms through reversible cysteine oxidation [8] [9]. Proteomic studies reveal that aging is associated with specific changes in the redox states of proteins involved in protein translation, ubiquitin-proteasome function, and cytoskeletal organization, with many of these changes reversible by manipulating redox homeostasis [7].

Fungal Pathogenesis: Pathogenic fungi utilize complex thiol-based systems to survive oxidative stress encountered during infection. Glutathione-dependent enzymes (glutaredoxins, glutathione peroxidases) and thioredoxin systems enable fungal pathogens to neutralize host-derived oxidants and establish infections [10]. These systems represent potential targets for antifungal therapies, particularly as drug resistance becomes increasingly problematic [10].

Metabolic Regulation: Redox-sensitive cysteine residues regulate key metabolic enzymes, allowing metabolic pathways to respond to changes in cellular redox state. For example, oxidation of Cys358 in pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) decreases its activity in hyperglycemic conditions, potentially contributing to diabetic complications [6].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized redox signaling pathway from signal perception to physiological response:

The unique chemistry of the cysteine thiol group makes it ideally suited for its role as a cellular redox sensor. The nucleophilicity of the thiolate anion, the diversity of reversible oxidative modifications, and the ability of protein environments to tune cysteine reactivity collectively enable precise sensing of redox challenges and appropriate adaptive responses. As research in this field advances, several emerging areas deserve particular attention:

Chemical Biology Tools: The development of more sophisticated methods for site-specific manipulation of cysteine oxidation states will be crucial for establishing causal relationships between specific redox events and biological outcomes [6]. Bioorthogonal chemistry combined with genetic code expansion represents a particularly promising approach.

Systems-Level Understanding: Integrating redox proteomics with other functional genomics data will provide a more comprehensive view of redox regulation networks and their connections to other cellular processes. This systems biology approach will be essential for understanding how redox signaling becomes dysregulated in disease states.

Therapeutic Targeting: The growing recognition of redox-sensitive cysteine residues as regulatory switches in pathogenic organisms and disease processes highlights their potential as therapeutic targets [10] [6]. Developing targeted covalent inhibitors that specifically modulate redox-sensitive cysteines represents an innovative approach for treating conditions involving oxidative stress.

The study of cysteine-mediated redox signaling continues to reveal the sophisticated mechanisms by which cells perceive and respond to their metabolic and environmental circumstances. As our tools for investigating these processes become increasingly precise, we can anticipate new insights into both fundamental biology and novel therapeutic strategies.

The redox regulation of protein cysteine residues represents a fundamental mechanism in cellular signaling and homeostasis. This in-depth technical guide examines four key oxidative post-translational modifications (oxPTMs) that constitute a critical regulatory network in redox biology: S-sulfenylation, S-nitrosation, S-glutathionylation, and S-persulfidation. These reversible modifications function as molecular sensors that dynamically modulate protein function, structure, and interactions in response to changes in the cellular redox environment [11] [12]. The intricate interplay between these modifications forms a sophisticated signaling language that enables cells to adapt to oxidative stress, regulate metabolic pathways, and control physiological processes ranging from vasodilation to immune response [13] [14]. Disruption of this delicate balance contributes significantly to the pathogenesis of numerous human diseases, including cardiovascular disorders, neurodegeneration, and cancer [11] [15] [14]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of these modifications, focusing on their chemical foundations, detection methodologies, and functional consequences within the broader context of redox regulation research.

Defining the Modifications: Core Concepts and Chemical Profiles

The following table summarizes the core definitions, chemical signatures, and key functional roles of the four cysteine modifications.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Key Cysteine Oxidative Post-Translational Modifications

| Modification | Chemical Structure | Precursor Species | Key Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-sulfenylation [11] [16] | Cys-SOH | Hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), other ROS [11] | Redox sensor; precursor for other oxPTMs; protects against irreversible oxidation [11] [16] |

| S-nitrosation [17] | Cys-SNO | Nitric oxide (NO), nitrosating agents (e.g., Nâ‚‚Oâ‚„) [18] [17] | Cell signaling (vasodilation, neurotransmission); regulation of kinase/phosphatase activity [17] |

| S-glutathionylation [15] [12] | Cys-S-SG | Oxidized glutathione (GSSG), sulfenic acid intermediate [12] | Protection from oxidative damage; redox regulation of metabolic and signaling proteins [15] [12] |

| S-persulfidation [13] [14] | Cys-SSH | Hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S), polysulfides (Hâ‚‚Sâ‚™) [13] [14] | Redox signaling; protection against oxidative stress; regulation of metabolism and inflammation [13] [14] [19] |

Formation Pathways and Interrelationships

The four modifications do not exist in isolation but are interconnected through shared biochemical pathways. The following diagram illustrates their formation and relationships.

Diagram 1: Cysteine Modification Pathways

S-sulfenylation represents the initial oxidative step, forming a sulfenic acid derivative (Cys-SOH) upon reaction with reactive oxygen species (ROS) like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) [11] [16]. This modification is highly reactive and often transient, serving as a crucial precursor for other oxPTMs. S-glutathionylation occurs when the electrophilic sulfur of a sulfenic acid reacts with the nucleophilic thiol of glutathione (GSH), forming a mixed disulfide [12]. This reaction can protect cysteine residues from irreversible over-oxidation to sulfinic (Cys-SO₂H) or sulfonic (Cys-SO₃H) acids [19]. S-nitrosation involves the attachment of a nitroso group to a cysteine thiol, forming S-nitrosothiols (RSNOs). This can occur through multiple mechanisms, including reaction with nitrous acid or transition metal-catalyzed pathways [17]. S-persulfidation (also called S-sulfhydration) generates a persulfide group (Cys-SSH) on the target protein. This can occur via the reaction of a protein thiol with hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) or, more efficiently, with polysulfides (H₂Sₙ) [13] [14]. Intriguingly, H₂S can also react with S-nitrosothiols to form persulfides, representing a potential cross-talk point between reactive nitrogen and sulfur species [13].

Quantitative Comparison of Modification Characteristics

A thorough understanding of these modifications requires comparing their biochemical properties, stability, and regulatory roles. The following table provides a detailed technical comparison to guide experimental design and data interpretation.

Table 2: Comprehensive Biochemical and Functional Comparison of Cysteine Modifications

| Characteristic | S-sulfenylation | S-nitrosation | S-glutathionylation | S-persulfidation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Half-Life | Seconds to minutes [16] | Minutes to hours | Minutes to hours [12] | Minutes [13] |

| Key Detection Methods | Dimedone probes [20] [16], DYn-2 [20] | Biotin-switch technique, Saville-Griess assay | Anti-GSH antibodies, biotinylated GSH esters [12] | Tag-switch assay, SSP4 probe [13] [14] |

| Reversibility | Highly reversible | Reversible | Reversible [12] | Highly reversible |

| Primary Regulatory Role | Early oxidative stress sensor | Signaling molecule in vasodilation, neurotransmission [17] | Protection from over-oxidation, redox regulation [12] | Hâ‚‚S-mediated signaling, oxidative stress defense [13] |

| Enzymatic Reversal Systems | Thioredoxin, Glutaredoxin (via reduction of disulfides) | Thioredoxin, S-nitrosoglutathione reductase | Glutaredoxin, Sulfiredoxin | Thioredoxin, Sulfiredoxin [13] |

| Estimated Abundance | 5-12% of cysteines oxidized (normal conditions) [11] | Tissue and protein-specific | Significant during oxidative stress | 10-25% of liver proteome [13] |

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Accurate detection of these labile modifications presents significant technical challenges. This section outlines key experimental workflows and reagents essential for rigorous research in this field.

Key Detection Workflows

Protocol for S-Sulfenylation Detection Using Chemical Probes

The most reliable method for detecting protein S-sulfenylation utilizes nucleophilic probes like dimedone that selectively trap the sulfenic acid intermediate. The following workflow is adapted from high-throughput proteomic studies [20].

- Cell Lysis and Blocking: Lyse cells under non-reducing conditions in the presence of alkylating agents such as iodoacetamide (IAM) or N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block free thiols and prevent post-lysis oxidation.

- Probe Incubation: Incubate the lysate with a sulfenic acid-specific probe (e.g., dimedone or its biotin-conjugated derivative DCP-Bio1) for 1-2 hours.

- Streptavidin Pulldown: If a biotinylated probe is used, capture the labeled proteins using streptavidin-coated beads.

- Washing and Elution: Wash beads stringently to remove non-specifically bound proteins. Elute the modified proteins for analysis.

- Downstream Analysis: Identify and quantify the modified proteins using techniques such as western blotting (for known targets) or mass spectrometry (for proteomic profiling) [20].

Protocol for S-Persulfidation Detection via Tag-Switch Assay

The tag-switch assay is a widely used method to selectively label protein persulfides, distinguishing them from other modifications like glutathionylation [13].

- Free Thiol Blocking: Treat the protein sample with methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS) to block all free thiols (Cys-SH) and other thiol-based modifications. MMTS also reacts with persulfides (Cys-SSH) to form Cys-S-S-CH₃.

- Selective Reduction: The key step involves treating the sample with a phosphine-based reducing agent (e.g., tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, TCEP) that selectively reduces the Cys-S-S-CH₃ derivative back to a free persulfide (Cys-SSH), but does not reduce disulfide bonds like those in S-glutathionylation.

- Labeling: The newly regenerated persulfide thiol is then labeled with a biotin- or fluorophore-tagged alkylating agent (e.g., biotin-maleimide).

- Detection: The labeled persulfidated proteins can be detected and analyzed via western blot, mass spectrometry, or other appropriate methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Studying Cysteine Redox Modifications

| Reagent / Tool | Chemical Nature | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Dimedone & DCP-Bio1 [20] [16] | 5,5-dimethyl-1,3-cyclohexanedione (and biotin conjugate) | Selective chemical probe that covalently labels and traps protein sulfenic acids (-SOH) for detection. |

| MMTS [13] [19] | Methyl Methanethiosulfonate | Small membrane-permeable alkylating agent used to block free thiols and as a key reagent in the tag-switch assay for persulfidation. |

| Biotin-HPDP | N-(6-(Biotinamido)hexyl)-3'-(2'-pyridyldithio)propionamide | Thiol-reactive biotinylation reagent used in techniques like the biotin-switch assay for S-nitrosation. |

| GYY4137 [14] | Morpholin-4-ium 4 methoxyphenyl(morpholino) phosphinodithioate | Slow-releasing hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) donor used to study the biological effects of Hâ‚‚S and induce protein persulfidation. |

| Sodium Nitroprusside [17] | Nitrosyl pentacyanoferrate(III) | Nitric oxide (NO) donor used in experimental settings to induce protein S-nitrosation. |

| AP39 [14] | Mitochondria-targeted Hâ‚‚S donor | A [10-oxo-10-(4-thiocyanatophenyl)decyl]triphenylphosphonium derivative that delivers Hâ‚‚S specifically to mitochondria. |

| 2-Amino-3-iodopyridine | 2-Amino-3-iodopyridine, CAS:104830-06-0, MF:C5H5IN2, MW:220.01 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4-Bromo-2-fluoro-1-iodobenzene | 4-Bromo-2-fluoro-1-iodobenzene, CAS:105931-73-5, MF:C6H3BrFI, MW:300.89 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Biological Roles and Implications for Drug Development

These cysteine modifications regulate critical cellular processes, and their dysregulation is implicated in major human diseases, making them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention.

Functional Consequences and Disease Links

S-sulfenylation in Redox Sensing and Stability: S-sulfenylation acts as a protective switch. By reversibly forming sulfenic acid, cysteine residues can be shielded from irreversible oxidation to sulfinic or sulfonic acids, which would lead to permanent protein damage [11] [16]. This modification also directly regulates protein function; for example, it can inhibit the activity of protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), thereby enhancing kinase signaling [11]. Its role is emerging in thrombotic disorders, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer [11].

S-nitrosation in Cell Signaling: S-nitrosation is a key mediator of nitric oxide (NO) signaling, regulating a wide range of physiological processes including vasodilation, neurotransmission, and immune response [17]. It exerts regulatory control over many enzymes, typically suppressing the activity of kinases like JNK and IKKβ, while also inhibiting protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) [17]. This modification is crucial in cardiovascular and neuronal systems, with alterations observed in conditions like heart failure and neurodegeneration.

S-glutathionylation in Metabolic Regulation and Cancer: This modification provides a mechanism for the redox regulation of central metabolic enzymes, effectively linking the cellular redox state to metabolic flux [15] [12]. It plays a vital protective role by shielding cysteines from irreversible oxidation during oxidative stress [12]. In cancer, altered S-glutathionylation patterns are linked to drug resistance, making the enzymes responsible for its reversal (e.g., glutaredoxin) potential therapeutic targets [15].

S-persulfidation in Physiology and Disease: Persulfidation is increasingly recognized as a fundamental redox regulation mechanism. It reprograms cysteine sensors in critical pathways involving metabolism (e.g., GAPDH), inflammation (e.g., NLRP3), and transcription (e.g., Keap1/NRF2) [14]. It has been shown to augment GAPDH activity and enhance actin polymerization, directly influencing cellular physiology [13]. Disrupted persulfidation is implicated in cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic syndromes, and cancer [14]. Endogenously produced Hâ‚‚S and subsequent persulfidation have been demonstrated as critical for physiological functions such as sperm viability [19].

Therapeutic Targeting and Future Directions

The strategic manipulation of cysteine oxPTMs represents a promising frontier in pharmacology. Several therapeutic approaches are under investigation:

- Hâ‚‚S Donors: Slow-releasing Hâ‚‚S donors like GYY4137 and mitochondria-targeted donors like AP39 are being explored for their ability to restore protective persulfidation signaling in cardiovascular disease, inflammation, and metabolic disorders [14]. The donor SG1002 has progressed to Phase II clinical trials (NCT02278276) [14].

- Diet-Derived Compounds: Natural polysulfides from garlic and isothiocyanates from cruciferous vegetables can modulate the cellular persulfidome and activate cytoprotective pathways like Nrf2, offering potential for nutritional interventions [14].

- Enzyme Inhibitors: Developing inhibitors or activators of the specific enzymes that write, erase, or read these modifications (e.g., CSE/CBS for Hâ‚‚S production, glutaredoxin for deglutathionylation) is a key strategy [15] [14].

A major challenge in the field is the narrow therapeutic margin of many donors and the difficulty in real-time quantification of these modifications in vivo. Future efforts will focus on developing smarter, tissue-targeted reagents and combining them with advanced detection techniques to translate our understanding of redox signaling into effective therapies.

The redox regulation of protein cysteine residues represents a fundamental mechanism in cellular signaling and homeostasis. Cysteine (Cys), a sulfur-containing amino acid, serves as a pivotal player in cellular redox regulation through its highly reactive thiol (–SH) group [21]. This thiol group is subject to a variety of posttranslational modifications (PTMs), such as sulfenylation, sulfinylation, glutathionylation, and nitrosylation, which modulate protein functions, redox homeostasis, and cellular responses to stress [21]. The dynamic nature of these modifications allows cells to rapidly respond to changing oxidative conditions, making cysteine-based redox switches crucial for adapting to physiological and pathological challenges. Dysregulation of these Cys-based PTMs has been implicated in disease progression, making them potential targets for therapeutic intervention [21]. Within this framework, three key regulatory systems have emerged as central players: the peroxiredoxin (Prx) family of peroxidases, the thioredoxin (Trx) system that maintains them in a reduced state, and sulfiredoxin-1 (SRXN1), which serves a unique repair function for oxidized Prxs [21] [22] [23].

Molecular Properties and Classification

Peroxiredoxins: Ubiquitous Thiol-Peroxidases

Peroxiredoxins (Prxs) are a fascinating group of thiol-dependent peroxidases (EC 1.11.1.15) that detoxify Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, aliphatic and aromatic hydroperoxides, and peroxynitrite [22]. They are ubiquitously expressed, with multiple isoforms present in most organisms (e.g., 3 isoforms in Escherichia coli, 5 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 6 in Homo sapiens, and 9 in Arabidopsis thaliana) [22]. The classification of Prxs has evolved from initial mechanistic distinctions to more sophisticated bioinformatics approaches:

Table 1: Peroxiredoxin Classification and Properties

| Classification | Representative Members | Conserved Cysteines | Structural Features | Reducing Partner |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical 2-Cys Prx | PrxI-IV (mammals), Tsa1 (yeast), AhpC (bacteria) | Cp and CR | Homodimeric with intersubunit disulfide | Thioredoxin |

| Atypical 2-Cys Prx | PrxV (mammals) | Cp and CR | Intrasubunit disulfide | Thioredoxin |

| 1-Cys Prx | PrxVI (mammals) | Cp only | No resolving cysteine | Glutathione, Ascorbate? |

The absolutely conserved peroxidatic cysteine (C~P~) residue serves as the site of oxidation by peroxides [23]. Mammalian cells express six Prx isoforms (PrxI to PrxVI), which are classified into the three groups above based on the location or absence of the resolving cysteine (C~R~) [23]. A more recent "global evolutionary classification" divided Prx proteins into six subfamilies: Prx1, Prx5, Prx6, Tpx, PrxQ, and AhpE, with mammalian PrxI-IV belonging to Prx1, PrxV to Prx5, and PrxVI to Prx6 [24].

The Thioredoxin System: Central Redox Hub

The thioredoxin (TRX) system is one of the major cellular antioxidant pathways that control redox homeostasis [25]. This system comprises NADPH, TRX reductase (TRXR), TRX itself, and the negative regulator TRX-interacting protein (TXNIP) [25]. TRXR is a selenoenzyme that utilizes reducing equivalents from NADPH generated by the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) to keep TRX in its reduced state [25]. Mammals possess three TRXR isoforms with distinct subcellular localizations: TRXR1 (cytoplasm), TRXR2 (mitochondria), and TRXR3 (testis-specific), along with corresponding TRX isoforms (TRX1 and TRX2) [25].

Thioredoxin is a 12-kD oxidoreductase protein with a characteristic tertiary structure termed the thioredoxin fold [26]. The active site contains a dithiol in a CXXC motif that is essential for its reductase activity [26]. The related glutaredoxins share many thioredoxin functions but are reduced by glutathione rather than a specific reductase, creating parallel but interconnected redox systems [26].

Sulfiredoxin-1: Redox Repair Enzyme

Sulfiredoxin-1 (SRXN1) is an essential component of the cellular redox system, specifically tasked with reversing the hyperoxidation of peroxiredoxins (Prxs), thereby restoring their peroxidase activity [21]. Human SRXN1 consists of 137 amino acids and has a molecular weight of approximately 14 kDa [21]. The Cys residue at position 99 (Cys99) in SRXN1 is directly involved in the enzymatic mechanism that facilitates the reduction of sulfinic acid, and mutations at this Cys abolish desulfinylation activity [21]. SRXN1 catalyzes the ATP-dependent reduction of Cys sulfinic acid (Cys-SOâ‚‚H) within hyperoxidized Prxs, a previously unknown reaction in biological systems [21].

Table 2: Key Redox Regulators: Genetic and Biochemical Properties

| Redox Component | Human Gene | Protein Size | Key Structural Motifs | Cellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRXN1 | SRXN1 | 14 kDa (137 aa) | Critical Cys99 | Cytosol |

| Typical 2-Cys Prx | PRDX1-PRDX4 | ~22 kDa per subunit | PxxxTxxC~P~ motif | Cytosol, Mitochondria, Nucleus, Secretory Pathway |

| Thioredoxin 1 | TXN | 12 kDa | CXXC active site motif | Cytoplasm |

| Thioredoxin Reductase 1 | TXNRD1 | ~55 kDa subunit | Selenocysteine residue | Cytoplasm |

Catalytic Mechanisms and Functional Roles

The Peroxiredoxin Catalytic Cycle

The catalytic cycle of Prxs begins with the nucleophilic attack of the peroxidatic cysteine (C~P~-Sâ») on the peroxide substrate, resulting in the formation of cysteine sulfenic acid (C~P~-SOH) and the release of water or alcohol [22] [23]. The C~P~ of Prx is oxidized by peroxides very rapidly with second-order rate constants of 10â¶-10⸠Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹, which are 5-7 orders of magnitude higher than those for small thiols [23]. This exceptional reactivity is enabled by a conserved transition state involving an extensive hydrogen bond network that comprises the C~P~ thiolate anion, peroxide, Thr and Pro residues within a universal PXXXTXXC~P~ active site motif, and a conserved Arg residue [23].

In the next step, resolution of the sulfenic acid intermediate occurs through disulfide bond formation. For typical 2-Cys Prxs, the sulfenic acid reacts with the resolving cysteine (C~R~-SH) from the other subunit to form an intersubunit disulfide bond [22]. For atypical 2-Cys Prxs like PrxV, this disulfide forms within the same subunit [23]. This resolution step requires a localized unfolding of structures around the C~P~ that removes the S~P~OH from the "fully folded" (FF) active site and exposes it in the "locally unfolded" (LU) form for disulfide bond formation [22]. The disulfide form is then reduced by thioredoxin to complete the catalytic cycle [22].

Thioredoxin System Redox Transfer

The thioredoxin system operates as a redox relay that transfers reducing equivalents from NADPH to target proteins [25]. The process begins with TRXR utilizing NADPH to reduce its FAD cofactor, which then reduces the active site disulfide in TRX [26]. Reduced TRX, with its CXXC motif in the dithiol state, can then reduce disulfide bonds in target proteins such as Prxs [26]. For Trx1, this process involves attack of Cys32 on the oxidized group of the substrate, followed immediately by disulfide bond formation with Cys35, thereby transferring two electrons to the substrate [26]. Oxidized Trx1 is then reduced by thioredoxin reductase, completing the cycle [26].

Sulfiredoxin-1-Mediated Repair of Hyperoxidized Peroxiredoxins

During their catalytic cycle, particularly under conditions of high oxidative stress, the sulfenic acid intermediate (C~P~-SOH) of Prxs can be further oxidized to sulfinic acid (C~P~-SOâ‚‚H), leading to irreversible inactivation [21]. SRXN1 catalyzes the ATP-dependent reduction of this sulfinic acid modification, restoring the catalytic cysteine to its reduced state [21]. The mechanism involves a unique ATP-dependent process where SRXN1 forms a covalent intermediate with the oxidized Prx, followed by thiol-mediated reduction [21]. This repair function is specific to 2-Cys peroxiredoxins and represents a critical defense mechanism against oxidative damage [21].

Figure 1: Integrated Redox Cycles of Peroxiredoxins, Thioredoxin, and Sulfiredoxin-1. This diagram illustrates the catalytic cycle of peroxiredoxins (Prx) in peroxide reduction, their regeneration by the thioredoxin (Trx) system, and the repair of hyperoxidized Prx by sulfiredoxin-1 (SRXN1).

Redox Signaling in Cellular Processes

Regulation of Immune Cell Function

The TRX system plays a particularly important role in immune cell activation and function [25]. Upon T cell activation, the TRX1-TRXR1 system is upregulated and supports massive proliferation by providing reducing equivalents to ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), which is essential for deoxyribonucleotide (dNTP) production during DNA biosynthesis [25]. Genetic deletion of Txnrd1 in mice results in impaired expansion of activated T cells during viral infections, demonstrating its critical role in adaptive immunity [25]. Interestingly, Txnrd1-deficient T cells do not display increased levels of ROS, indicating that the primary defect is in nucleotide synthesis rather than antioxidant defense [25].

B cells utilize a more flexible redox system, with the ability to employ glutaredoxin 1 (GRX1) as a compensatory pathway when TRX is unavailable [25]. However, innate-like B cells (B1 and marginal zone B cells) resemble T cells in their strict requirement for the TRX system, as they are unable to engage GRX1 compensation [25]. This differential requirement highlights the cell type-specific adaptations in redox regulation.

Redox Control of Gene Expression

The TRX system regulates several transcription factors, including NF-κB, AP-1, HIF1α, and the antioxidant master regulator Nrf2 [25] [26]. TRX1 reduces a disulfide bond in NF-κB, promoting its DNA-binding activity [26]. Similarly, TRX1 indirectly increases AP-1 DNA-binding activity by reducing the DNA repair enzyme redox factor 1 (Ref-1), which in turn reduces AP-1 [26]. This creates a redox regulation cascade that fine-tunes gene expression in response to oxidative stimuli.

SRXN1 itself is transcriptionally regulated by both Nrf2 and AP-1, creating feedback loops that enhance cellular antioxidant capacity [21]. The SRXN1 promoter contains a functional antioxidant response element (ARE) at -228 bp from the transcription start site that is responsive to Nrf2, as well as AP-1 binding sites that mediate induction in response to other stimuli [21].

Role in Cell Survival and Death Decisions

Redox regulators influence critical decisions between cell survival and death through multiple mechanisms. TRX1 regulates apoptosis by suppressing ASK1 activity through direct binding [25]. Under normal conditions, reduced TRX1 binds to ASK1 and inhibits its kinase activity. During oxidative stress, TRX1 is oxidized and dissociates from ASK1, allowing ASK1 to activate JNK and p38 MAPK pathways that promote apoptosis [25].

Peroxiredoxins also participate in cell death decisions through their chaperone activity. Upon hyperoxidation, some Prxs can form high molecular weight complexes that gain molecular chaperone function, protecting proteins from aggregation under stress conditions [24]. This switch from peroxidase to chaperone function represents an adaptive response to oxidative stress.

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Assessing Redox Status and Enzyme Activity

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Studying Redox Regulators

| Methodology | Application | Key Insights Provided |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive kinetics with HRP or catalase | Measuring Prx reaction rates | Second-order rate constants of 10â¶-10⸠Mâ»Â¹sâ»Â¹ for peroxide reduction |

| Stopped-flow fluorescence | Monitoring reaction intermediates | Identification of sulfenic acid formation and resolution kinetics |

| Site-directed mutagenesis | Functional analysis of catalytic residues | Cys99 in SRXN1 and C~P~ in Prxs are essential for activity |

| Redox-sensitive GFP probes | Compartment-specific redox measurements | Spatial organization of redox signaling |

| Thioredoxin trapping mutants | Identifying TRX substrates | CXXC motif mutants trap intermediate disulfides |

Transcriptional Regulation Studies

The transcriptional regulation of SRXN1 has been elucidated through promoter analysis techniques. Deletion constructs and site-directed mutagenesis of the SRXN1 promoter identified functional ARE and AP-1 binding sites [21]. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays confirmed the binding of Nrf2 and AP-1 transcription factors to these regulatory elements [21]. Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated that Nrf2 knockdown decreases SRXN1 promoter activity, while Nrf2 activators like tBHQ significantly enhance its activity [21].

Genetic Manipulation Approaches

Genetic studies including knockout mouse models have been instrumental in defining the physiological functions of redox regulators. Mice lacking peroxiredoxin 1 or 2 develop severe hemolytic anemia and are predisposed to certain hematopoietic cancers, while Peroxiredoxin 1 knockout mice have a 15% reduction in lifespan [24]. Tissue-specific knockout approaches, such as Txnrd1 deletion in T cells, have revealed cell-type-specific requirements for redox enzymes [25]. Similarly, CRISPR-Cas9 screens identified Txnrd1 as a positive regulator of the antitumor response of CD8+ T cells [25].

Figure 2: Transcriptional Regulation of SRXN1 and its Functional Consequences. This diagram illustrates how oxidative stress activates transcription factors Nrf2 and AP-1, which bind to antioxidant response elements (ARE) in the SRXN1 promoter to increase SRXN1 expression, ultimately leading to repair of hyperoxidized peroxiredoxins and restoration of redox homeostasis.

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Role in Liver Disease

SRXN1 has emerged as a significant factor in liver pathophysiology [21]. Through its regulation of Cys sulfinylation across a broad spectrum of liver diseases, SRXN1 modulates redox-sensitive signaling pathways that govern inflammation, apoptosis, and cell survival [21]. The critical role of SRXN1 in regulating oxidative stress and cellular signaling through its interaction and desulfinylation of target proteins is crucial to maintaining cellular function under pathological conditions [21]. A deeper understanding of SRXN1-mediated redox regulation may offer a novel therapeutic avenue to mitigate Cys oxidation and improve clinical outcomes in various liver disease contexts [21].

Connections to Cancer and Aging

Redox regulators display dual roles in cancer, functioning as both tumor suppressors and promoters depending on context [21] [25]. The TRX system is considered a promising target in cancer therapy, with inhibitors undergoing clinical evaluation [25]. Similarly, SRXN1 has been implicated in cancer progression, with studies showing it promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth by inhibiting TFEB-mediated autophagy and lysosome biogenesis [27]. SRXN1 also stimulates hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis and metastasis through modulating ROS/p65/BTG2 signaling [27].

The thioredoxin system has been directly linked to cellular senescence and aging-related diseases [28]. The progressive decline of redox homeostasis with age contributes to the pathogenesis of multiple age-related conditions, making redox regulators potential targets for therapeutic intervention in aging [28].

Therapeutic Targeting Strategies

Several strategies have emerged for targeting redox regulators therapeutically:

TRX System Inhibitors: Compounds like auranofin inhibit thioredoxin reductase and have shown promise in cancer therapy by disrupting redox balance in rapidly dividing cells [25].

Nrf2 Activators: Since SRXN1 is transcriptionally regulated by Nrf2, compounds that activate Nrf2 signaling could enhance cellular antioxidant defenses in degenerative diseases [21].

SRXN1 Expression Modulation: Both upregulation and inhibition of SRXN1 may have therapeutic value depending on context, with SRXN1 inhibition potentially sensitizing cancer cells to oxidative stress-inducing therapies [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Studying Redox Regulation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Plasmids | SRXN1, PRDX1-6, TXN, TXNRD1 | Overexpression studies | Functional analysis of wild-type vs. mutant proteins |

| Mutant Constructs | C99S SRXN1, C~P~ mutants of Prxs | Structure-function studies | Determining essential catalytic residues |

| Knockout Models | Global and tissue-specific KO mice | Physiological studies | Defining essential functions in different tissues |

| Specific Inhibitors | Auranofin (TRXR inhibitor) | Therapeutic targeting studies | Evaluating consequences of system inhibition |

| Activity Probes | Redox-sensitive fluorescent dyes | Real-time monitoring | Visualizing compartment-specific redox changes |

| Antibodies | Anti-SRXN1, anti-Prx-SOâ‚‚H | Detection in cells and tissues | Assessing expression and oxidation status |

| Conduritol B Tetraacetate | Conduritol B Tetraacetate|CAS 25348-63-4 | Bench Chemicals | |

| Aleoe-emodin triacetate | Triacetyl Aloe-emodin | 1,8-Bis(acetyloxy)-3-[(acetyloxy)methyl]-9,10-anthracenedione | Bench Chemicals |

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The field of cysteine redox regulation continues to evolve with several emerging research directions. The development of more specific tools to monitor and manipulate individual redox systems in specific cellular compartments remains a priority. Understanding the complex interactions and potential redundancies between the TRX, glutathione, and other redox systems in different cell types and disease contexts represents another important frontier. The therapeutic targeting of these systems requires greater specificity to avoid disrupting essential redox homeostasis while achieving desired therapeutic effects.

Single-cell analysis of redox states and the integration of redox proteomics with other omics approaches will likely provide unprecedented insights into the spatial and temporal organization of redox signaling networks. Furthermore, the role of redox regulation in emerging areas such as the microbiome-brain axis and immunometabolism represents fertile ground for future investigation.

In conclusion, Sulfiredoxin-1, peroxiredoxins, and the thioredoxin system represent interconnected components of the cellular redox regulatory network that fine-tune cysteine-based signaling events. Their study continues to yield fundamental insights into cellular homeostasis and provides promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in diverse disease contexts.

The cellular antioxidant response is a critical defense mechanism against oxidative stress, a pervasive challenge in both physiological homeostasis and pathological states. This whitepaper delineates the sophisticated transcriptional machinery governed by the transcription factors Nrf2 and AP-1, which coordinately regulate a vast network of cytoprotective genes. Central to this discussion is their synergistic and context-dependent regulation of target genes, such as sulfiredoxin (SRXN1), through shared cis-regulatory elements. Framed within the broader context of redox regulation of protein cysteine residues, this review integrates current mechanistic insights, experimental methodologies, and therapeutic implications. The content is specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking a deeper understanding of these pathways for therapeutic intervention in diseases characterized by oxidative damage, including neurodegenerative disorders and cancer.

Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the cellular antioxidant defenses, is a well-established contributor to the pathogenesis of a wide array of diseases [29] [30]. The nervous system is particularly vulnerable, and oxidative stress is a significant factor in neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [30]. At a molecular level, the thiol group of cysteine residues in proteins is a primary target of ROS, leading to a spectrum of post-translational modifications (PTMs)—including sulfinylation, glutathionylation, and nitrosylation—that profoundly influence protein function, redox homeostasis, and cellular signaling [29].

To manage this constant threat, cells have evolved intricate transcriptional programs that enhance the expression of antioxidant and detoxification enzymes. The transcription factors Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) and Activator Protein-1 (AP-1) stand as pivotal regulators of this inducible defense system [31] [32]. This review will explore their unique and overlapping roles, the molecular mechanisms of their activation, and their coordinated regulation of a shared genetic battery, with a specific focus on the redox regulator sulfiredoxin-1.

The Nrf2-Keap1 Signaling Axis

Molecular Architecture and Basal Regulation

Nrf2 is a member of the Cap 'n' Collar (CNC) subfamily of basic-region leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors [33]. Its activity is tightly controlled by its cytoplasmic repressor, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1). Under homeostatic conditions, Nrf2 is constitutively targeted for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This process is facilitated by Keap1, which acts as a substrate adaptor for a Cullin 3 (Cul3)-based E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Nrf2 is sequestered in the cytoplasm via binding through its two motifs, the ETGE and DLG motifs, which interact with the Kelch domain of Keap1 [33]. This arrangement ensures a rapid turnover of Nrf2, maintaining low basal levels under non-stressed conditions.

Mechanism of Activation by Inducers

The activation of Nrf2 is primarily post-translational and hinges on the modification of critical cysteine residues within Keap1 and Nrf2 itself. Keap1 contains numerous cysteine residues that function as redox sensors. Specific inducers, including the isothiocyanate sulforaphane (SFN) and tert-butylhydroquinone (tBHQ), modify key cysteine residues (e.g., C151 in the BTB domain and C273 and C288 in the linker region) leading to a conformational change in Keap1 [34] [35]. This modification disrupts the Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase activity, impairing Nrf2 ubiquitination. Consequently, newly synthesized Nrf2 escapes degradation, stabilizes, and translocates to the nucleus [33] [35].

Recent evidence also underscores the direct role of Nrf2 cysteine residues. Mutation of critical cysteines in Nrf2 (Cys235, Cys311, Cys316, Cys414, and Cys506) enhances its binding to Keap1, increases its polyubiquitination, and shortens its half-life. Furthermore, mutations at Cys119, Cys235, and Cys506 can impede the binding of Nrf2 to the Antioxidant Response Element (ARE) and its recruitment of the coactivator CBP/p300, illustrating that Nrf2 itself is a redox-sensitive protein [34].

Transcriptional Programming via the ARE

Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 heterodimerizes with small Maf (sMaf) proteins and binds to the cis-acting Antioxidant Response Element (ARE), with a core sequence of 5'-TGACXXXGC-3', in the promoter regions of its target genes [33]. This program coordinates the expression of over 200 genes involved in glutathione biosynthesis (e.g., GCLC, GCLM), ROS detoxification (e.g., NQO1, HO-1), xenobiotic metabolism, and NADPH regeneration [33]. The loss of Nrf2 in knockout mice leads to increased susceptibility to various chemical toxicities, autoimmune dysfunction, and cancer, highlighting its non-redundant role as a "guardian of redox homeostasis" [34] [33].

The AP-1 Signaling Pathway

Composition and Regulation

AP-1 is not a single transcription factor but a collection of dimeric complexes composed of members from the Jun (c-Jun, JunB, JunD), Fos (c-Fos, FosB, Fra-1, Fra-2), ATF, and Maf subfamilies [29] [32]. These proteins contain a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) domain that mediates dimerization and DNA binding. The composition of the AP-1 dimer determines its binding affinity and transcriptional activity [32]. AP-1 activity is rapidly induced by a diverse array of stimuli, including growth factors, cytokines, and cellular stresses. Its regulation is complex, occurring at both transcriptional and post-translational levels, with kinases from the MAPK pathways (JNK, ERK, p38) playing a central role in phosphorylating and activating components like c-Jun [32].

Genomic Targets and Functional Diversity

AP-1 dimers recognize either the TPA response element (TRE; 5'-TGAG/CTCA-3') or the cAMP response element (CRE) to regulate genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and inflammation [32]. Its role in the antioxidant response is context-dependent. While AP-1 can drive pro-survival gene expression, it can also contribute to tumor promotion and inflammatory processes. The functional outcome of AP-1 activation is thus highly specific to the cellular context, dimer composition, and nature of the stimulus.

Integrated Regulation: The Sulfiredoxin (SRXN1) Case Study

The gene encoding Sulfiredoxin-1 (SRXN1) serves as a paradigm for the integrated regulation of the antioxidant response by Nrf2 and AP-1, bridging the gap between transcriptional control and cysteine redox regulation.

Functional Role of SRXN1: SRXN1 is a key redox repair enzyme that catalyzes the ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine-sulfinic acid (Cys-SO2H) on hyperoxidized Peroxiredoxins (Prxs), thereby reactivating these critical antioxidant enzymes [31] [29]. This activity places SRXN1 at the heart of the cellular machinery that reverses oxidative cysteine modifications.

Promoter Architecture: The promoter of the human

SRXN1gene contains a conserved ARE. Notably, the core ARE sequence embeds a proximal AP-1 binding site, a common feature in many Nrf2 target genes [31] [36]. This physical overlap suggests a mechanism for synergistic or competitive interactions.Dual Transcriptional Control:

- Nrf2-dependent Regulation: SRXN1 has been conclusively identified as an Nrf2 target gene. The primary functional ARE (ARE1) is located at -228 bp from the transcription start site. Nrf2 activators like tBHQ and synthetic triterpenoids (e.g., CDDO-TFEA) potently induce

SRXN1transcription, and this induction is abrogated upon Nrf2 knockdown [31] [29] [36]. - AP-1-dependent Regulation: AP-1 also regulates

SRXN1expression. For instance, in neurons, synaptic activity inducesSRXN1via AP-1, conferring protection against oxidative stress [31] [36]. The specific composition of the AP-1 dimer (e.g., Jun–Jun or Jun–Fos) can influence the transcriptional output from the shared ARE/AP-1 element.

- Nrf2-dependent Regulation: SRXN1 has been conclusively identified as an Nrf2 target gene. The primary functional ARE (ARE1) is located at -228 bp from the transcription start site. Nrf2 activators like tBHQ and synthetic triterpenoids (e.g., CDDO-TFEA) potently induce

Biological and Therapeutic Significance: The Nrf2-mediated induction of SRXN1 is a crucial part of the protective response in models of hyperoxic lung injury [31]. Furthermore, in liver diseases, SRXN1 has been shown to modulate redox-sensitive signaling pathways governing inflammation, apoptosis, and cell survival, making it a potential therapeutic target [29]. This dual regulation allows the cell to fine-tune the expression of a critical repair enzyme through multiple signaling pathways, ensuring a robust defense against various oxidative insults.

Experimental Methods for Studying Nrf2 and AP-1

To investigate the complex regulation of Nrf2 and AP-1, researchers employ a multifaceted toolkit. The table below summarizes key experimental protocols and the reagents used to dissect these pathways.

Table 1: Key Experimental Protocols for Nrf2 and AP-1 Research

| Methodology | Key Steps | Application in Nrf2/AP-1 Research |

|---|---|---|

| Luciferase Reporter Assay [29] [32] | 1. Clone promoter region (e.g., SRXN1 or synthetic ARE) into luciferase vector.2. Co-transfect with Nrf2/AP-1 expression plasmids.3. Treat with compounds (e.g., SFN, EGCG).4. Measure luciferase activity. |

Quantifies transcriptional activity and promoter binding; identifies functional ARE/AP-1 elements and assesses effects of pharmacological activators/inhibitors. |

| Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) [34] | 1. Cross-link proteins to DNA.2. Shear chromatin.3. Immunoprecipitate with antibody against Nrf2 or AP-1 components.4. Reverse cross-links and quantify bound DNA via PCR. | Confirms direct, physical binding of transcription factors to specific genomic regions (e.g., the SRXN1 promoter). |

| Gene Expression Analysis (qRT-PCR) [37] | 1. Treat cells (e.g., SH-SY5Y) with inducer.2. Extract total RNA and synthesize cDNA.3. Perform quantitative PCR with primers for NQO1, HO-1, SRXN1. |

Measures endogenous mRNA levels of target genes to confirm pathway activation. |

| Protein Stability & Ubiquitination Assays [34] [35] | 1. Treat cells with proteasome inhibitor (MG132).2. Immunoprecipitate Nrf2.3. Immunoblot with anti-ubiquitin antibody. | Demonstrates Keap1-dependent ubiquitination and stabilizes Nrf2 for detection. |

| Cysteine Mutagenesis [34] | 1. Generate Nrf2 or Keap1 mutants with Cys-to-Ala substitutions.2. Express in knockout cells (e.g., Nrf2-KO MEFs).3. Assess protein half-life, Keap1 binding, and transcriptional activity. |

Identifies critical cysteine residues for chemical sensing, protein-protein interactions, and degradation. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Investigating Nrf2 and AP-1 Pathways

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Utility |

|---|---|

| Cell Lines | |

Nrf2-Knockout (KO) Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) [34] |

Essential control for confirming Nrf2-specific effects; used to reconstitute signaling with mutant proteins. |

| PC-3 AP-1 Human Prostate Cancer Cells [32] | Model for studying AP-1 signaling and its crosstalk with Nrf2 in a cancer context. |

| Chemical Activators & Inhibitors | |

| Sulforaphane (SFN) [32] [35] | Natural isothiocyanate that modifies Keap1 cysteines (e.g., C151), leading to Nrf2 stabilization and activation. |

| tert-Butylhydroquinone (tBHQ) [34] [37] | A well-characterized Nrf2 activator used as a positive control in many experimental setups. |

| Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) [32] | A polyphenol from green tea that can modulate both Nrf2 and AP-1 pathways. |

| MG132 [34] | Proteasome inhibitor; used to stabilize Nrf2 and accumulate ubiquitinated proteins for analysis. |

| Molecular Biology Tools | |

| ARE-Luciferase Reporter Plasmid [29] [37] | Standard tool for measuring Nrf2 transcriptional activity in high-throughput screens. |

| Keap1 Cysteine Mutant Plasmids (e.g., C151A, C273A) [35] | Used to define the functional role of specific sensor cysteines in Keap1. |

| Nrf2 Cysteine Mutant Plasmids (e.g., C235A) [34] | Used to investigate the direct redox-sensing capability of Nrf2. |

| sMaf Protein Expression Vectors [33] | Necessary partners for Nrf2 DNA binding; used to study dimerization and ARE binding. |

| Calindol Hydrochloride | Calindol Hydrochloride, CAS:729610-18-8, MF:C21H21ClN2, MW:336.9 g/mol |

| DL-Isocitric acid trisodium salt | Isocitric Acid Trisodium Salt | High Purity | RUO |

Pathway Crosstalk and Therapeutic Implications

Regulatory Interplay between Nrf2 and AP-1

Nrf2 and AP-1 do not function in isolation; they engage in extensive crosstalk. Studies using dietary chemopreventive compounds like a combination of sulforaphane and EGCG demonstrated a concerted modulation of both Nrf2 and AP-1 pathways in prostate cancer cells [32]. Bioinformatic analyses have identified conserved transcription factor binding sites in the promoter regions of Nrf2 and AP-1 components, suggesting a potential network of mutual regulation [32]. This interplay can be synergistic or antagonistic, depending on the cellular context and the specific dimeric composition of AP-1. Furthermore, the physical overlap of ARE and AP-1 sites in promoters like that of SRXN1 provides a genomic platform for this integration, allowing the cell to compute diverse stress signals into a precise transcriptional output.

Relevance to Disease and Drug Discovery

The Nrf2 pathway is a promising therapeutic target for numerous conditions driven by oxidative stress and inflammation.

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: In Alzheimer's disease (AD), Nrf2 activity is diminished, and its activation is being pursued as a strategy to combat oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. The Bach1 protein, a transcriptional repressor of Nrf2, has emerged as a complementary target, with combined Nrf2 activation and Bach1 inhibition representing a novel, multipronged therapeutic approach [38].

- Cancer: The dual role of Nrf2 in cancer presents a challenge. In healthy cells, Nrf2 activation is chemopreventive. However, cancer cells frequently harbor mutations in

KEAP1orNRF2itself, leading to constitutive Nrf2 activation that promotes tumor survival and resistance to therapy [34] [33]. This dichotomy necessitates cell-specific therapeutic strategies. - Liver and Lung Diseases: The protective role of the Nrf2-SRXN1 axis has been demonstrated in models of lung injury and various liver pathologies, including acute liver injury, alcoholic liver disease, and fibrosis [31] [29].

The development of multi-target-directed ligands (MTDLs) represents a cutting-edge approach, particularly for complex diseases like AD. For instance, chromone-containing MTDLs have been designed to simultaneously target acetylcholinesterase and activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway, demonstrating significant antioxidant effects in vitro [37].

Visualizing the Core Nrf2-Keap1-SRXN1 Signaling Pathway

The following diagram synthesizes the key components and interactions of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling axis and its regulation of the SRXN1 gene, integrating inputs from the AP-1 pathway.

Diagram 1: Nrf2-Keap1-SRXN1 Signaling Pathway. Under basal conditions, Keap1 targets Nrf2 for proteasomal degradation. Oxidative stress modifies critical cysteine residues in Keap1, leading to Nrf2 stabilization and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, Nrf2 dimerizes with sMaf proteins and binds the ARE to drive transcription of SRXN1. The AP-1 pathway can provide additional input at the shared ARE/AP-1 site in the SRXN1 promoter.

The transcriptional control of the antioxidant response by Nrf2 and AP-1 represents a sophisticated and layered defense system fundamental to cellular integrity. The Nrf2-Keap1 axis acts as a primary sensor for electrophiles and oxidants, launching a broad cytoprotective program. Its interplay with the context-dependent AP-1 pathway, exemplified by their co-regulation of the cysteine repair enzyme SRXN1, allows for the fine-tuning of gene expression in response to a diverse set of stimuli. Understanding the molecular nuances of this regulatory network, including the critical roles of specific cysteine residues as redox sensors, is paramount. This knowledge not only deepens our fundamental understanding of redox biology but also paves the way for rational drug design targeting Nrf2 and AP-1 in a range of debilitating diseases, from neurodegeneration to cancer. Future research, leveraging the experimental tools and models discussed, will continue to unravel the complexities of this system and its therapeutic potential.

Redox biology represents a fundamental aspect of cellular function, where reduction-oxidation (redox) reactions govern critical processes from energy production to gene expression. The term "redox" originates from the combination of "reduction" and "oxidation," describing chemical processes involving electron transfer between reactants [39]. Within biological systems, reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide (O₂•â»), hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are continuously generated through multiple sources, including the mitochondrial electron transport chain, endoplasmic reticulum, and NADPH oxidase (NOX) systems [39] [40]. For decades, ROS were predominantly viewed as toxic byproducts of metabolism that indiscriminately damage cellular macromolecules. However, our understanding has evolved to recognize that ROS also function as crucial signaling molecules that regulate a myriad of physiological processes, including insulin signaling, vascular tone, and immunometabolism [41].

This dual nature of reactive species led to the conceptual distinction between redox eustress and distress. Eustress describes oxidative stress under physiological conditions where ROS function as signaling molecules, while distress refers to the pathological state where excessive or misplaced ROS cause macromolecular damage [39]. The balance between these states is maintained by sophisticated antioxidant systems, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and the thioredoxin system, which collectively maintain cellular redox homeostasis [39] [40]. The nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) acts as a master regulator of antioxidant responses, elevating the synthesis of key antioxidant molecules like SOD, catalase, NADPH, and glutathione (GSH) when needed [39]. This review examines the intricate mechanisms distinguishing physiological redox signaling from pathological oxidative damage, with particular emphasis on the redox regulation of protein cysteine residues and its implications for therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Cysteine-Mediated Redox Signaling

The Cysteine Redox Switch: Post-Translational Modifications

At the heart of redox signaling lies the reversible oxidation of cysteine residues within proteins. The human proteome contains approximately 210,000 cysteine residues, with thousands exhibiting sensitivity to oxidants [40]. Cysteine residues possess a highly reactive thiol group (-SH) that undergoes a variety of reversible oxidative post-translational modifications in response to redox changes, functioning as a molecular "switch" for protein structure-function dynamics [40] [42]. The specific modifications that cysteine residues can undergo include:

- S-sulfenylation (-SOH): Formation of sulfenic acid when thiol groups are oxidized by Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ at low levels

- Disulfide bond formation (-S-S-): Creation of intra- or inter-molecular disulfide bonds between nearby thiols

- S-glutathionylation (-SSG): Formation of mixed disulfide bonds between sulfenic acids and glutathione

- S-persulfidation (-SSH): Modification by hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) reacting with sulfenic acids or disulfides

- S-nitrosylation (SNO): Modification by reactive nitrogen species

- S-sulfinylation (-SOâ‚‚H): Further oxidation to sulfinic acid

- S-sulfonylation (-SO₃H): Irreversible oxidation to sulfonic acid [39] [40] [21]

Table 1: Major Reversible Cysteine Oxidative Modifications in Redox Signaling

| Modification | Chemical Structure | Regulatory Enzyme | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-sulfenylation | -SOH | --- | Protein activity modulation |

| Disulfide bond | -S-S- | Protein disulfide isomerase | Protein folding & oligomerization |

| S-glutathionylation | -SSG | Glutaredoxin | Protection from overoxidation |

| S-persulfidation | -SSH | Sulfurtransferases | Hâ‚‚S-mediated signaling |

| S-nitrosylation | -SNO | --- | NO-mediated signaling |

| S-sulfinylation | -SOâ‚‚H | Sulfiredoxin | Regulatory inactivation |

These oxidative modifications are highly dynamic and can be reversed by specific cellular reductants. For instance, sulfiredoxin-1 (SRXN1) specifically catalyzes the ATP-dependent reduction of cysteine sulfinic acid (Cys-SOâ‚‚H) in peroxiredoxins and other target proteins, playing a critical role in protecting cells from excessive oxidative damage and maintaining redox balance [21]. The reactivity of specific cysteine residues is dictated by distinct electrostatic microenvironments and subcellular localization, with solvent-exposed cysteines in certain sequence motifs being particularly susceptible to oxidation [43] [42].

Spatiotemporal Control of Redox Signaling

The biological outcome of reactive species generation depends critically on the spatiotemporal context of their production. The role of ROS is context-dependent and varies according to the cellular environment, compartmentalization, exposure period, and concentration [41]. Different cellular compartments maintain distinct redox environments and contain specialized ROS-producing and ROS-scavenging systems:

- Mitochondria: Complexes I and III of the electron transport chain are major sources of mitochondrial ROS (mtROS), alongside mitochondrial-localized proteins like NOX4, p66shc, and monoamine oxidases [41]. Mitochondria-localized SOD2 converts O₂•⻠to H₂O₂.

- Cytosol: NADPH oxidases (NOXs) are transmembrane enzymes that generate superoxide by transferring electrons from NADPH to oxygen [41]. Xanthine oxidase also produces H₂O₂ and O₂•⻠in the cytoplasm.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum: Oxidative protein folding in the ER involves ERO1 and QSOX enzymes that generate Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ as a byproduct when driving disulfide bond formation [40].

- Peroxisomes: House several oxidases like acyl-CoA oxidase and D-amino acid oxidase that generate Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ during metabolic reactions [40].

Compartmentalized ROS biosynthesis allows for localized redox regulation and ensures that redox signals are delivered to specific targets without causing widespread damage [40]. For example, communication between mitochondrial ROS and cytosolic ROS significantly affects endothelial function and angiogenesis [41]. This precise control mechanism enables specific signaling outcomes while minimizing collateral damage, representing a crucial feature distinguishing eustress from distress.

Distinguishing Redox Eustress from Distress: Molecular Determinants

Characteristics of Physiological Eustress

Redox eustress is characterized by localized, transient, and specific ROS production that activates signaling pathways essential for physiological processes. At physiological levels, ROS and hydrogen sulfide (Hâ‚‚S) act as oxidation-reduction signaling molecules that regulate a myriad of cellular processes through reversible oxidation of reactive cysteine residues in target proteins [40]. Key features of redox eustress include:

- Specific molecular targets: Redox eustress involves selective oxidation of specific cysteine residues on target proteins rather than widespread macromolecular damage. For example, quantitative cysteine redox proteomics has revealed that different cysteines within the same protein display dramatic differences in susceptibility to S-sulfenylation [43].

- Reversible modifications: Physiological signaling primarily involves reversible oxidative modifications such as S-sulfenylation, disulfide formation, and S-glutathionylation that can be rapidly reversed by cellular reduction systems [39] [40].

- Activation of adaptive responses: Eustress often activates protective transcriptional programs through transcription factors like NRF2 and FOXO, which enhance cellular antioxidant capacity and repair mechanisms [39] [40].

- Controlled production from specific enzymes: Physiological ROS generation occurs through tightly regulated systems including growth factor-activated NOX enzymes and mitochondrial respiration under normal physiological conditions [39] [41].

Notably, mild or transient increases in ROS or Hâ‚‚S levels have been shown to delay aging and extend lifespan in model organisms, demonstrating the beneficial roles of redox eustress in organismal physiology [40].

Features of Pathological Distress

In contrast to eustress, pathological redox distress is characterized by widespread, sustained, and uncontrolled oxidative damage that overwhelms cellular defense systems. The accumulation of ROS in cells directly damages biomolecules such as nucleic acids, membrane lipids, structural proteins, and enzymes, leading to cellular dysfunction or death [39]. Key aspects of redox distress include:

- Macromolecular damage: Distress causes oxidative damage to DNA (including missense mutations, truncation mutations, and DNA breakage), lipid peroxidation, and protein carbonylation [39].

- Irreversible modifications: While physiological modifications are typically reversible, distress can lead to irreversible oxidation such as sulfonylation (-SO₃H) that permanently inactivates proteins [40] [21].

- Disruption of redox-sensitive signaling: Dysregulation in redox modifications leads to aberrant redox signaling, disrupting normal cellular processes [39].