Benchmarking Engineered Redox Proteins: From AI-Driven Design to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to evaluate the efficiency of engineered redox proteins against their native counterparts.

Benchmarking Engineered Redox Proteins: From AI-Driven Design to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to evaluate the efficiency of engineered redox proteins against their native counterparts. It explores the foundational principles of redox potential and electron transfer, details cutting-edge design methodologies including AI and machine learning, addresses critical challenges in stability and function, and establishes robust validation protocols. By integrating insights from recent advancements in structural biology, computational prediction, and functional assays, this review serves as a guide for the rational design and effective benchmarking of next-generation redox proteins for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Decoding the Blueprint: Fundamental Principles of Native Redox Protein Function

Biological electron transfer (ET) is a fundamental process that underpins essential functions from cellular respiration to photosynthesis. The efficiency of these processes is critically dependent on the finely tuned reduction potentials (RP) of metalloprotein cofactors, which determine the direction and driving force of electron flow [1] [2]. In native systems, evolution has optimized these potentials through precise control of the protein environment surrounding redox-active metal clusters. The emerging field of redox protein engineering seeks to understand and manipulate these principles to create proteins with enhanced or novel functions for applications in bioenergy, biosensing, and therapeutics [3] [4]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of native versus engineered systems, examining the core mechanisms, experimental data, and methodologies driving this rapidly advancing field.

Core Mechanisms of Redox Potential Tuning

The redox potential of a metalloprotein's active site is not an intrinsic property of the metal cofactor alone. Instead, it is exquisitely tuned by the surrounding protein matrix through several well-defined physical mechanisms.

Primary Coordination Sphere Effects

The most direct influence comes from the identity and geometry of direct ligand atoms bound to the metal center. Replacing a coordinating cysteine with histidine in a [2Fe-2S] cluster, for example, significantly raises the reduction potential by altering the electron density at the iron atoms [1]. In blue copper proteins, the constrained geometry enforced by thiolate ligands from cysteine and imidazole nitrogen from histidine creates an entatic state that contributes to their high potentials [3].

Secondary Coordination Sphere and Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonding networks to metal-coordinating residues or cluster sulfides can stabilize reduced states and raise reduction potentials. In azurin, systematic mutations of secondary sphere residues that hydrogen-bond to the copper-coordinating histidine demonstrated measurable potential shifts of up to 40 mV without altering the primary metal ligation [4]. For iron-sulfur proteins, hydrogen bonds to the inorganic sulfide atoms significantly modulate cluster electronics [1].

Long-Range Electrostatic and Dielectric Effects

The global protein electrostatic environment and solvent exposure create a dielectric constant that influences the energy required to add or remove electrons. Burial of a redox center in a hydrophobic environment typically raises the potential due to the thermodynamic cost of charge stabilization in a low-dielectric medium [1] [3]. Computational studies have shown that the protein matrix acts as a "wide band-gap semiconductor" with redox centers serving as dopant sites for electron localization [3].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms for Tuning Redox Potential in Metalloproteins

| Tuning Mechanism | Spatial Scale | Typical Effect Range | Example Experimental Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Coordination | Short-range (direct binding) | Wide (≥ 200 mV) | Cys → His ligand substitution in [2Fe-2S] clusters [1] |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Short-to-medium range | Moderate (50-100 mV) | Mutations affecting H-bond to T1 Cu in laccases [4] |

| Electrostatic Environment | Long-range (global protein) | Narrow to Moderate (10-80 mV) | Surface charge mutations in azurin [4] |

| Solvent Exposure | Long-range | Moderate (30-150 mV) | Hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic residue mutations near active site [3] |

Comparative Performance: Native vs. Engineered Systems

Iron-Sulfur Proteins

Iron-sulfur (Fe-S) proteins represent ideal model systems for understanding redox tuning principles due to their structural diversity and central metabolic roles.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Native vs. Engineered Fe-S Proteins

| System Type | Redox Potential Range | Electron Transfer Rate | Stability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Fe-S Proteins | -460 mV to +390 mV [1] | Highly efficient, biologically optimized | High in native environment | Electron transfer in respiration, photosynthesis [1] |

| Computationally Designed | Predictable tuning via ML (MAE ~40 mV) [1] | Theoretically optimized | Variable; requires validation | High-throughput design of novel redox chains [1] |

| Rational Mutants | Targeted shifts of 50-200 mV [1] | May be compromised by misfolding | Generally high with careful design | Fundamental studies of structure-function relationships [1] |

Multicopper Oxidases (MCOs) and Blue Copper Proteins

The copper center in these proteins has been extensively engineered for enhanced electrocatalytic applications, particularly for oxygen reduction reactions in biofuel cells.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Native vs. Engineered Copper Proteins

| System Type | Redox Potential Range | Catalytic Efficiency | Key Modifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Fungal Laccases | ~+780 mV vs. SHE [4] | High O2 reduction at low overpotentials | N/A (wild-type) |

| Engineered High-Potential Laccases | Up to +950 mV vs. SHE [4] | Enhanced ORR efficiency | Axial ligand mutations, H-bond network optimization [4] |

| Native Azurin | ~+310 mV vs. SHE [4] | Efficient single-electron transfer | N/A (wild-type) |

| Engineered Azurin Variants | +240 to +380 mV vs. SHE [4] | Maintained or slightly altered ET rates | Secondary sphere Phe incorporations [4] |

Hydrogenases

[NiFe] and [FeFe] hydrogenases efficiently catalyze H2 oxidation/production using earth-abundant metals instead of precious metals, operating with nearly no overpotential [4]. Protein engineering has successfully modulated their catalytic bias (inherent preference for H2 oxidation vs. production) by tuning the redox potentials of electron transfer iron-sulfur clusters within the protein, demonstrating how electron transfer centers can influence catalytic function beyond simple electron delivery [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Machine Learning for Redox Potential Prediction

The FeS-RedPred framework exemplifies modern approaches to redox property prediction, achieving a mean absolute error of ~40 mV competitive with state-of-the-art computational methods while offering significantly higher throughput [1].

Experimental Protocol: FeS-RedPred Implementation

- Data Curation: Compile a curated dataset of Fe-S proteins with available structural data (PDB) and experimentally determined redox potentials (371 entries including wild-types and mutants) [1]

- Descriptor Calculation: Automatically extract 66 molecular descriptors from PDB structures across three spatial ranges:

- Short-range (3-5 Å): Local atomic environments around each Fe/S atom

- Medium-range (8-16 Å): Residues in second coordination sphere

- Long-range: Global protein physicochemical properties [1]

- Model Training: Implement Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) regression using structure-derived descriptors as features and experimental redox potentials as targets [1]

- Validation: Perform cross-validation and external testing to achieve mean absolute error of ~40 mV, competitive with DFT methods at significantly lower computational cost [1]

Computational Chemistry Approaches

For accurate redox potential prediction of metal complexes in solution, sophisticated solvation models are essential. A recently developed three-layer micro-solvation model combines DFT geometry optimizations with explicit water molecules and implicit solvation, achieving errors of just 0.01-0.04 V for Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ redox potentials [5].

Experimental Protocol: Three-Layer Micro-Solvation Model

- First Layer Optimization: Perform DFT-based geometry optimization of the metal complex (e.g., [Fe(H₂O)₆]²⁺/³⁺) in gas phase using functionals like ωB97X-D3 or B3LYP-D3 [5]

- Second Layer Addition: Add 12 explicit water molecules at ~4.5 Å radius to capture strong solute-solvent interactions [5]

- Third Layer Addition: Incorporate 18 additional explicit water molecules at ~6.5 Å radius to represent extended solvation shell [5]

- Implicit Solvation: Apply continuum solvation model (e.g., CPCM) to account for bulk solvent effects [5]

- Energy Calculation: Compute free energy differences between oxidized and reduced states, referencing to standard hydrogen electrode [5]

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Redox Protein Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | Machine learning prediction of redox potentials from structural descriptors | FeS-RedPred framework for Fe-S proteins [1] |

| Three-Layer Micro-Solvation Model | Computational prediction of metal complex redox potentials in solution | Accurate prediction of Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ potentials (error <0.04 V) [5] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Rational engineering of primary and secondary coordination spheres | Commercial kits for introducing axial ligand mutations in laccases [4] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of high-quality protein structures for descriptor calculation | Structures of ferredoxins, Rieske proteins, azurins [1] |

| Directed Evolution Platforms | Laboratory evolution of redox proteins with enhanced properties | Increasing redox potential and stability of fungal laccases [4] |

The comparative analysis of native and engineered redox proteins reveals a sophisticated interplay between biological optimization and human design principles. Native systems achieve remarkable efficiency through evolutionary refinement of complex protein environments that fine-tune cofactor redox potentials for specific biological functions. Engineered systems are progressing toward comparable performance through multiple strategies: rational design based on fundamental principles, machine learning prediction enabling high-throughput optimization, and directed evolution mimicking natural selection in laboratory settings.

The most promising approaches combine computational prediction with experimental validation, leveraging tools like FeS-RedPred for initial screening followed by precise characterization of designed variants. As these methodologies mature, the capacity to custom-design redox proteins with predetermined potentials will transform applications ranging from biofuel cells to pharmaceutical development, ultimately harnessing the principles of biological electron transfer for technological innovation.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three fundamental classes of redox-active proteins: hemoproteins, iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, and blue copper proteins. For researchers evaluating engineered versus native redox protein efficiency, understanding the distinct electron transfer properties, structural features, and functional applications of these protein classes is essential. The data presented herein, drawn from experimental and computational studies, offers a foundation for selecting appropriate redox protein platforms for specific applications in bioelectronics, biocatalysis, and pharmaceutical development.

Comparative Analysis of Native Redox Proteins

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three native redox protein classes, highlighting their structural and functional differences.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Native Redox Protein Classes

| Feature | Hemoproteins | Iron-Sulfur (Fe-S) Proteins | Blue Copper Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prosthetic Group | Heme (iron-protoporphyrin IX) [3] [6] | [2Fe-2S], [3Fe-4S], [4Fe-4S] clusters [7] | Type 1 copper center [8] [9] |

| Metal Oxidation States | Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ [6] | Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ in a coupled cluster [7] | Cu⁺/Cu²⁺ [8] |

| Primary Biological Functions | Oxygen transport/storage (e.g., myoglobin), catalytic oxidation (e.g., Cytochrome P450), electron transfer (e.g., cytochromes) [3] [6] | Electron transfer, enzyme catalysis, regulatory roles in gene expression [7] | Electron transfer in photosynthesis and respiration [8] [9] |

| Typical Reduction Potential Range | Broad, varies significantly with protein environment [10] | Can be very low, suitable for high-energy electrons [11] | +200 mV to >1000 mV [9] |

| Key Structural Features | Iron coordinated by porphyrin N; axial ligands from protein (e.g., His) [3] [6] | Iron atoms coordinated by inorganic S and cysteine S (or His) [7] | Distorted tetrahedral geometry; strong Cu-S(Cys) bond; two His N ligands [8] [9] |

Protein Engineering and Manipulation of Properties

Protein engineering techniques, including rational design and directed evolution, are powerful tools for creating novel redox proteins with predictable structures and desirable functions [3]. The table below compares key engineering strategies and outcomes for the three protein classes.

Table 2: Engineering Strategies and Functional Outcomes for Redox Proteins

| Aspect | Hemoproteins | Iron-Sulfur Proteins | Blue Copper Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Engineering Methods | Rational design of helical bundles; heme re-constitution with synthetic cofactors [6] [10] | Site-directed mutagenesis of cluster ligands and protein interface [11] | Site-directed mutagenesis of axial ligands and second-sphere residues [9] |

| Engineered Function Examples | De novo designed oxygen transport proteins, peroxidases, and photosensitive proteins [6] | Manipulation of electron transfer pathways in multi-cluster systems [11] | Systematic tuning of redox potential over a >400 mV range [9] |

| Key Tunable Parameters | Oxygen affinity, catalytic activity, cofactor incorporation [6] [10] | Reduction potential, cluster stability, partner specificity [11] | Redox potential (via H-bonding, axial ligation, electrostatics) [9] |

| Applications of Engineered Variants | Drug metabolite generation (P450 fusions), biosensors [3] | Hybrid catalysis, biomolecular electronics [3] | Biosensors, biofuel cells [3] |

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative data on redox potentials and electron transfer efficiency are critical for comparing native and engineered proteins.

Table 3: Experimentally Measured Redox Potentials of Selected Blue Copper Proteins [9]

| Protein | Experimental E° (mV) | Key Structural Features Influencing Potential |

|---|---|---|

| Stellacyanin | ~260 | Axial Gln ligand, strong hydrogen bonding to Cys sulfur [9] |

| Azurin | ~305 | S(Met) and carbonyl oxygen as axial ligands [9] |

| Plastocyanin | ~375 | S(Met) axial ligand [9] |

| Laccase | ~550 | No axial Met ligand [9] |

| Rusticyanin | ~680 | Strong hydrogen-bonding network, lack of axial Met [9] |

| Ceruloplasmin | >1000 | Hydrophobic environment, unique coordination sphere [9] |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Rational Design of a Heme-Binding Protein

This protocol outlines the creation of de novo hemoproteins, a key achievement in protein engineering [6].

- Objective: Design a stable protein scaffold that binds heme and exhibits a desired function, such as oxygen binding or peroxidase activity.

- Design Phase: Select a simple, stable protein fold, such as a four-helix bundle. Use computational software to model the placement of histidine residues in the hydrophobic core to serve as axial ligands for the heme iron.

- Synthesis and Expression: Gene synthesis for the designed protein sequence and expression in a suitable system, such as E. coli.

- Reconstitution: Purify the apoprotein (without heme). Incubate with hemin (Fe(III)-protoporphyrin IX) under reducing conditions to incorporate the cofactor.

- Characterization:

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Confirm heme incorporation by identifying the characteristic Soret and Q bands.

- Functional Assays: Test for target functionality (e.g., oxygen binding via equilibrium dialysis, peroxidase activity with colorimetric substrates).

- Structural Validation: Determine the atomic structure using X-ray crystallography or NMR to verify the designed geometry [6].

Protocol for Computational Prediction of Redox Potentials

Computational methods are vital for predicting the effects of mutations on redox potential, guiding rational design [9].

- Objective: Calculate the redox potential (E°) of a blue copper protein or mutant.

- Structure Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution crystal structure of the protein. Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms and assigning protonation states.

- System Setup:

- QM/MM Optimization: Perform a combined Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM) geometry optimization. The copper ion and its direct ligands (e.g., 2xHis, Cys, Met) are treated with QM, while the rest of the protein and solvent is treated with MM.

- QM-Cluster Calculation: Define a larger QM region (~70-340 atoms) encompassing the metal site and surrounding protein residues. Embed this cluster in a continuum solvent model with a defined dielectric constant (ε=20-80).

- Energy Calculation: Using a density functional (e.g., TPSS or B3LYP) and a basis set (e.g., def2-SV(P)), calculate the free energy difference between the reduced (Cu⁺) and oxidized (Cu²⁺) states.

- Potential Calculation: Convert the free energy difference to a redox potential by referencing to a standard electrode (e.g., Standard Hydrogen Electrode). The accuracy for relative potentials can reach a mean absolute deviation of 0.09 V [9].

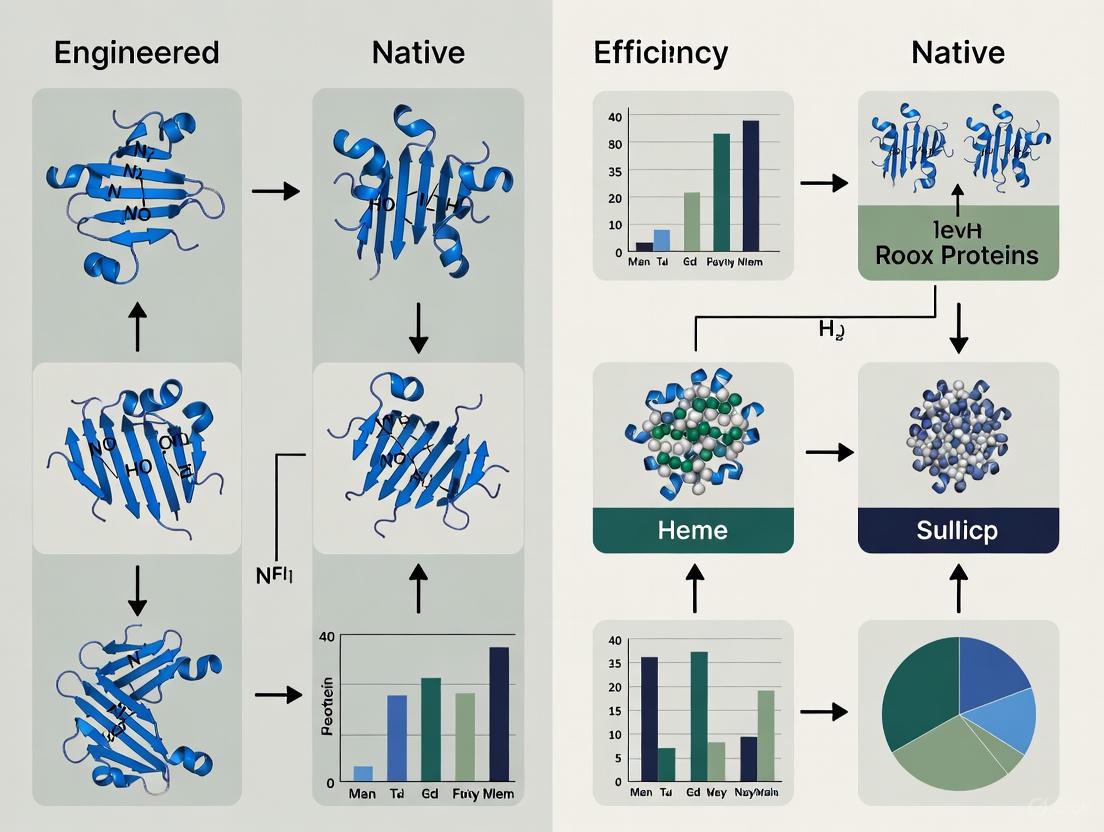

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the key experimental and computational processes described in this guide.

Rational Protein Engineering Workflow

Computational Redox Potential Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Redox Protein Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hemin | The Fe(III) form of heme; used for reconstituting apo-hemoproteins in vitro [6] [10] | Commercial source; stable for storage. |

| Ferredoxins | Small Fe-S cluster proteins; used as electron donors in assays with P450s and other redox enzymes [3] [11] | Can be sourced from spinach, clostridia; specific type depends on partner enzyme. |

| Plastocyanin | A well-characterized blue copper protein; often used as a benchmark in electron transfer studies and computational method validation [9] | Can be isolated from plants or produced recombinantly. |

| Computational Software | For modeling protein structures, calculating energies, and predicting redox properties. | Software packages enabling QM/MM and DFT calculations (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | For creating specific amino acid changes in protein sequences to study structure-function relationships. | Commercial kits available from various suppliers. |

| Expression Systems | Host organisms for producing recombinant redox proteins. | E. coli is common; yeast or insect cells may be used for more complex proteins. |

The protein environment acts as a sophisticated molecular stage, meticulously engineered to fine-tune function. For redox proteins, which are pivotal in processes like photosynthesis and cellular respiration, this environment is not a passive backdrop but an active participant in guiding molecular recognition, complex formation, and electron transfer efficiency. The interplay between solvent dynamics, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding creates a responsive matrix that dictates protein behavior. This guide objectively compares the functional efficiency of native and engineered redox proteins by examining how these environmental factors are modulated. The evaluation is grounded in experimental data, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to assess the impact of protein engineering on core biological functions.

Theoretical Background: Fundamental Forces in the Protein Environment

Electrostatic Interactions

Electrostatic forces are long-range organizers of the protein environment. According to Coulomb's law, the interaction energy between two charges ( q1 ) and ( q2 ) separated by a distance ( r ) in a solvent with dielectric constant ( \varepsilons ) is given by: [ G{int}(solvent) = 332 \frac{q1 q2}{\varepsilon_s r} ] where energy is in kcal/mol and distance in Ångströms [12]. The surrounding medium profoundly modulates this interaction; the dielectric constant drops from approximately 80 in bulk water to 2-4 in the protein interior, creating a "dielectric barrier" that influences binding and catalysis [12]. Charged residues are typically found on protein surfaces, as burying them in the nonpolar interior carries a severe energetic penalty of up to -15.8 kcal/mol for a monovalent ion with a radius of 2.5 Å [12].

Hydrogen Bonding

Hydrogen bonds represent a more localized and specific type of electrostatic interaction, crucial for maintaining structural integrity and enabling catalytic activity. In enzymatic reactions, the formation of low-barrier hydrogen bonds (LBHBs) with diffuse proton distributions can play a decisive role in catalysis. These strong, short hydrogen bonds can facilitate spontaneous proton transfers on a picosecond timescale, as observed in quantum-classical molecular dynamics simulations of HIV-1 protease [13].

Solvent Dynamics

Water is not merely a passive solvent but an integral component of the protein environment. The collective hydrogen-bonding network of water molecules at the protein interface exhibits dynamics distinct from bulk water. Terahertz-time domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) probes these sub-picosecond collective motions (0.3–6 THz), revealing how protein-surface electrostatic properties either retard or accelerate surrounding water dynamics [14] [15]. This hydration shell influences molecular recognition, complex stability, and ultimately, function.

Table 1: Key Physical Interactions in the Protein Environment

| Interaction Type | Theoretical Basis | Typical Range | Role in Protein Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatics | Coulomb's Law: ( G{int} = 332 \frac{q1 q2}{\varepsilons r} ) | 5–10 Å (long-range) | Molecular recognition, binding specificity, steering charged ligands |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Dipole-dipole interaction with partial covalent character | ~1.5–3.0 Å (short-range) | Structural stability, catalytic proton transfers, substrate orientation |

| Solvent Dynamics | Modulation of collective hydrogen-bond vibrations | ~2–3 hydration shells | Entropic driving forces for binding, mediating electron transfer |

Experimental Comparison: Native vs. Engineered Redox Proteins

The Model System: FNR and PetF Complex

The photosynthetic redox couple from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, consisting of the flavoenzyme ferredoxin-NADP+-reductase (FNR) and the electron transfer protein ferredoxin-1 (PetF), serves as an exemplary model. Their transient complex is primarily stabilized by electrostatic charge-charge interactions between basic residues on FNR and acidic residues on PetF, alongside a hydrophobic environment near the redox centers [15]. Interestingly, while multiple ferredoxin isoforms share similar acidic residue patterns, not all interact functionally with FNR, hinting at subtler environmental fine-tuning beyond simple electrostatic complementarity [15].

Probing Solvent Dynamics with Terahertz Spectroscopy

Experimental Protocol: Terahertz-Time Domain Spectroscopy (THz-TDS)

- Objective: To measure changes in the collective hydration dynamics of FNR, PetF, and their transient complex.

- Methodology: A Ti:sapphire oscillator (800 nm, 80 MHz) generates THz pulses via a photoconductive antenna. The transmitted electric field through a 100 μm thick sample cell (z-cut quartz windows) is measured via electro-optical sampling in a ZnTe crystal [15].

- Key Measurements: The frequency-dependent absorption coefficient ( \alpha(\nu) ) and refractive index ( n(\nu) ) are extracted. Changes in the sub-picosecond relaxation time of water molecules (τ) report on the retardation or bulk-like recovery of solvent dynamics.

- Sample Preparation: Proteins are expressed, purified, and stored at -80°C. Mixtures for the complex are prepared fresh on the day of measurement [15].

Table 2: Solvent Dynamics in Native and Complexed Redox Proteins

| Protein System | Relaxation Time (ps) | Interpretation | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Water | ~7 | Reference value for unperturbed water | Baseline for comparison |

| FNR (alone) | 8–9 | Retarded solvent dynamics | Positive protein surface charges create a more ordered hydration shell |

| PetF (alone) | 8–9 | Retarded solvent dynamics | Negative protein surface charges create a more ordered hydration shell |

| FNR:PetF Complex | 8–9 | Retarded solvent dynamics | Complex interface maintains an ordered water layer |

| FNR:PetF:NADP+ (Ternary) | ~7 | Bulk-like solvent dynamics | Substrate binding releases ordered water, making complex formation entropically favored [14] [15] |

The data reveals a critical finding: formation of the functional ternary complex (FNR:PetF:NADP+) is accompanied by a reorganization of the hydration shell into a more bulk-like state. This release of ordered water molecules provides a significant entropic driving force for molecular recognition and complex formation [15]. An engineered protein that fails to replicate this solvent-mediated entropic boost would likely show reduced efficiency, even if its surface charge complementarity appears optimal.

Quantifying Electrostatic Steering and Binding

Experimental Protocol: Computational Analysis of Binding Free Energy

- Objective: To identify ligand binding sites and quantify binding free energies without prior structural knowledge, using physics-based simulations.

- Methodology: GPU-accelerated Hamiltonian replica exchange molecular dynamics (HREMD) simulations are performed. Multiple replicas of the system explore a range of Hamiltonians, from fully interacting to non-interacting states, accelerating sampling. The Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) is then used to extract binding free energies [16].

- System: T4 lysozyme L99A mutant with small aromatic ligands (e.g., benzene) [16].

- Advantage over Docking: This method accounts for full atomistic detail, solvation effects, and statistical mechanical ensembles, overcoming limitations of empirical scoring functions and rigid receptor models in docking [16].

Table 3: Energetic Contributions of Protein Environment Factors

| Environmental Factor | Experimental System | Measured Energetic Contribution | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desolvation Penalty | Charged amino acid burial | Up to ~ -15.8 kcal/mol (unfavorable) [12] | Born solvation model |

| Charge-Charge Interaction | T4 Lysozyme L99A / Ligand | Part of overall ( \Delta G_{bind} ) | HREMD/MBAR [16] |

| Solvent Entropy (Entropic Gain) | FNR:PetF:NADP+ Complex | Significant contribution to ( \Delta G_{bind} ) (favorable) | THz-TDS [15] |

The rigorous computational approach confirms that electrostatic interactions within the protein environment are a major component of the total binding free energy. Engineered proteins must therefore balance the favorable energy from forming specific ion pairs against the unfavorable cost of dehydrating charged groups.

Hydrogen Bonding in Catalytic Function

Experimental Protocol: Quantum-Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD/AVB)

- Objective: To elucidate the role of hydrogen bonding and proton transfer in an enzymatic reaction.

- Methodology: The system is partitioned. Atoms directly involved in bond rearrangement (e.g., the catalytic aspartic dyad and substrate in HIV-1 protease) are treated quantum-mechanically using the approximate valence bond (AVB) method. The remaining protein and explicit solvent are treated with a classical molecular mechanics force field [13].

- Probe: The nature of hydrogen bonds (length, proton position distribution, single-well or double-well potential) is analyzed during different reaction stages.

Application of this protocol to HIV-1 protease revealed the formation of strong hydrogen bonds leading to spontaneous proton transfers. A single-well hydrogen bond was observed between the peptide nitrogen and an aspartate oxygen, with the proton diffusely distributed and transferring on a picosecond scale. This interaction was crucial for changing peptide-bond hybridization and activating the substrate [13]. This demonstrates how the protein environment tunes electronic properties via hydrogen bonding to achieve catalysis. An engineered enzyme must replicate such precise electrostatic preorganization to be effective.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Tools for Studying the Protein Environment

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Terahertz-Time Domain Spectrometer | Probes collective hydrogen-bond dynamics of water in the sub-ps regime. | Quantifying changes in hydration dynamics upon protein complex formation [15]. |

| GPU-Accelerated Computing Cluster | Runs long, complex molecular dynamics simulations with enhanced sampling methods. | Performing HREMD simulations for binding site identification and free energy calculations [16]. |

| Approximate Valence Bond (AVB) Software | Models bond breaking/formation and electron redistribution in a quantum region coupled to a classical environment. | Studying the role of low-barrier hydrogen bonds in enzymatic catalysis [13]. |

| Protein Expression & Purification Systems | Produces high-purity, functional native and engineered protein variants for biophysical studies. | Preparing samples of FNR, PetF, and isoforms for comparative THz-TDS analysis [15]. |

| Implicit Solvent Models (e.g., GBSA) | Provides a computationally efficient representation of solvent effects based on the Born model and related terms. | Initial screening and setup for free energy calculations in drug design [12] [16]. |

Comparative Analysis: Engineered vs. Native Protein Efficiency

The experimental data allows for a structured comparison of key performance metrics between native and engineered redox proteins. Efficiency is multi-faceted, encompassing not just binding strength but also the dynamics of complex formation and catalytic rate.

Table 5: Performance Comparison of Native vs. Engineered Redox Proteins

| Performance Metric | Native Protein Complex (e.g., FNR:PetF:NADP+) | Potential Pitfall in Engineered Proteins | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Specificity | High; driven by precise electrostatic surface complementarity. | Off-target binding if surface charge patterning is non-optimal. | Crystallography and NMR show specific basic-acidic residue pairs [15]. |

| Entropic Driving Force | Strong; entropically favored ternary complex with bulk-like solvent. | Weaker binding if engineered surface fails to release ordered water. | THz-TDS shows shift to τ ~7 ps in ternary complex [15]. |

| Catalytic Proficiency | High; enabled by finely-tuned hydrogen bonding networks and proton transfer. | Reduced catalytic rate (( k_{cat} )) if pre-organized electrostatic environment is disrupted. | MD/AVB shows spontaneous proton transfers in catalytic LBHBs [13]. |

| Binding Affinity (( K_d ), ( \Delta G )) | Optimized; balances electrostatic steering, desolvation, and hydrogen bonding. | Suboptimal ( \Delta G ) if one energetic component is overlooked in design. | HREMD/MBAR computes ( \Delta G ) consistent with experiment for native systems [16]. |

The efficiency of redox proteins is not solely encoded in their primary structure but is exquisitely fine-tuned by their environment. The presented experimental data underscores that solvent dynamics, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding are not independent factors but are deeply interconnected. A successful engineered protein must therefore be evaluated against this holistic framework. It is insufficient to design a protein with perfect surface charge complementarity if it fails to trigger the beneficial solvent reorganization observed in native complexes. Similarly, recreating a catalytic site requires more than positioning residues; it demands the precise electrostatic preorganization that facilitates the formation of functionally critical hydrogen bonds. Future engineering efforts must integrate experimental metrics that probe these environmental factors—such as terahertz spectroscopy for solvent dynamics and advanced simulations for electrostatics and bonding—to develop truly bio-equivalent or superior synthetic proteins.

Visualizing the Interplay in the Protein Environment

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts discussed in this guide, showing how fundamental physical forces in the protein environment integrate to fine-tune function.

The quest for efficient biocatalysts and biosensors has propelled research into engineering redox proteins that surpass the capabilities of their native counterparts. Defining the efficiency of these proteins—whether engineered or native—requires a rigorous framework grounded in three essential metrics: electron transfer kinetics, catalytic turnover, and thermodynamic stability. Native redox proteins, such as cytochromes and blue copper proteins, inherently possess these properties, which have been optimized through evolution for specific biological functions [3]. However, for applications in industrial biocatalysis, biofuel cells, or biosensors, these native properties often require enhancement.

Protein engineering, through rational design and directed evolution, aims to manipulate these core metrics. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these essential properties, offering a standard set of protocols and benchmarks for researchers evaluating engineered versus native redox protein efficiency. The objective data and methodologies presented herein are crucial for the rational development of next-generation biocatalysts for drug development and other biotechnological applications.

Quantitative Metrics for Comparative Analysis

Metric 1: Electron Transfer Kinetics

Electron transfer (ET) is the foundational process in redox biochemistry. Its efficiency is quantified by the electron transfer rate constant (k_et). In biological systems, electrons often tunnel over impressive distances of several nanometers via a "hopping" mechanism between closely spaced cofactors shielded by the protein matrix [2].

The self-exchange rate constant is a key parameter for understanding a protein's innate electron transfer capability, often measured by NMR line-broadening studies or specialized isotopic labeling experiments [17]. For example, a classic study on the blue copper protein stellacyanin, using isotopes ^63^Cu and ^65^Cu, yielded a self-exchange rate constant of 1.2 × 10^5 M^-1 s^-1 [17].

Table 1: Comparative Electron Transfer Rate Constants

| System | Method of Analysis | Rate Constant (k) | Midpoint Potential (E°') |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stellacyanin (Native Blue Copper Protein) | Isotopic Exchange EPR [17] | 1.2 × 10^5 M^-1 s^-1 | Not Specified |

| Shewanella oneidensis (Intact Cells, Direct ET) | Single-Turnover Voltammetry [18] | ~1 s^-1 | ~0 V vs. SHE |

| Shewanella oneidensis (Intact Cells, Flavins) | Turnover Voltammetry [18] | Significantly accelerated | -0.2 V vs. SHE |

| Cytochrome c with TMPD Mediator | Linear Sweep Voltammetry [19] | 1.6 × 10^4 M^-1 s^-1 | Matched mediator |

Metric 2: Catalytic Turnover and Efficiency

For an enzyme, catalytic efficiency is measured by its ability to convert substrate to product. The key parameters are the Michaelis Constant (KM), the maximum velocity (Vmax), and the catalytic constant (kcat). These are encapsulated in the Michaelis-Menten equation: v0 = (Vmax [S]) / (KM + [S]) [20].

The value of KM, which is the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax, provides a measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate. A lower KM indicates higher affinity. The turnover number (kcat), which is Vmax divided by the total enzyme concentration, represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme site per unit time. The catalytic efficiency is then defined by the ratio kcat / KM [20]. Engineering efforts often focus on lowering the activation energy (ΔG‡), thereby increasing kcat and the overall catalytic efficiency, a principle that applies equally to hydrolytic enzymes and oxidoreductases.

Metric 3: Thermodynamic Stability

Thermodynamic stability is a critical metric for determining the practical utility of a redox protein under operational conditions such as elevated temperatures or extreme pH. It is quantitatively assessed by the protein's folding free energy (ΔGfolding) and its melting temperature (Tm). For redox proteins, the stability of the active site, which often houses a metal cofactor, is paramount.

Computational methods, particularly Density Functional Theory (DFT), are powerful tools for predicting thermodynamic stability. For instance, in the design of single-atom catalysts (SACs) using polyoxometalates (POMs) like [VW~5~O~19~]^3-^, stability is evaluated by calculating the binding energy (E_b) of the transition metal to the support and the cohesive energy of the resulting structure [21]. A highly negative binding energy indicates a stable, synthesisable catalyst that resists metal atom aggregation. These DFT-calculated thermodynamic descriptors are essential for screening potential catalysts before experimental validation.

Table 2: Thermodynamic and Catalytic Descriptors from Computational Studies

| System | Computational Method | Key Thermodynamic Metric | Key Catalytic Metric (ΔG~H*~) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM@V-POM (e.g., V@V-POM) | DFT [21] | Binding Energy, Cohesive Energy | 0.03 eV (Excellent) | High thermodynamic stability and superior HER activity. |

| TM@V-POM (e.g., Zn@V-POM) | DFT [21] | Binding Energy, Cohesive Energy | -0.01 eV (Excellent) | High stability and activity comparable to Pt. |

| Pt (111) Benchmark | Experimental & Computational [21] | - | 0.09 eV | Benchmark for HER catalyst performance. |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) NNP | Neural Network Potential [22] | - | MAE for Reduction Potential: ~0.26-0.51 V | Machine learning model for predicting redox properties. |

Experimental Protocols for Metric Determination

Protocol 1: Linear Sweep Voltammetry for Electron Transfer Kinetics

Objective: To determine the rate and equilibrium constants for electron transfer reactions between a redox protein and a soluble mediator.

Method Summary: This technique exploits the fact that redox proteins often do not transfer charge directly to electrodes but readily react with small molecule mediators. The perturbation of the mediator's LSV response in the presence of the protein is analyzed to extract kinetic and thermodynamic data [19].

Detailed Workflow:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing a known concentration of the electron transfer mediator (e.g., N,N,N',N'-tetramethylphenylenediamine) in a suitable buffer.

- Baseline Measurement: Perform an LSV scan of the mediator solution alone to establish its unperturbed voltammogram.

- Protein Introduction: Add the redox protein (e.g., cytochrome c) to the solution. The protein must not interact directly with the electrode surface.

- Perturbation Measurement: Record a new LSV scan. The presence of the protein will perturb the mediator's voltammogram due to electron exchange.

- Data Analysis: Use digital simulation to fit the perturbed voltammogram. This analysis yields the forward and reverse rate constants (k~forward~, k~reverse~) for the protein-mediator electron exchange, as well as the formal reduction potential (E°') of the protein [19].

Figure 1: LSV Workflow for Electron Transfer Kinetics.

Protocol 2: DFT Analysis of Catalytic and Thermodynamic Properties

Objective: To computationally predict the thermodynamic stability and catalytic activity of a designed redox catalyst or engineered enzyme.

Method Summary: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations allow for the in silico optimization of geometric and electronic structures to determine key metrics before synthetic work begins [21].

Detailed Workflow:

- Cluster Model Definition: Construct an initial atomic model of the system (e.g., a transition metal atom anchored on a POM cluster).

- Geometry Optimization: Use a DFT package (e.g., Gaussian 16) to optimize the system's geometry to its lowest energy state, confirming the absence of imaginary frequencies.

- Property Calculation:

- Stability Metrics: Calculate the binding energy (E~b~) and cohesive energy to assess thermodynamic stability.

- Activity Descriptors: Calculate the Gibbs free energy of hydrogen adsorption (ΔG~H*~) for HER or similar descriptors for other reactions.

- Electronic Properties: Determine the d-band center, Bader charges, and HOMO-LUMO gaps to understand electronic origins of activity [21].

- Validation: Correlate computed descriptors (e.g., ΔG~H*~) with known experimental benchmarks to validate the computational model.

Figure 2: DFT Workflow for Stability and Activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Redox Protein Efficiency Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| N,N,N',N'-Tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) | Electron Transfer Mediator | Shuttling electrons between electrodes and cytochrome c for kinetic studies [19]. |

| Flavins (FMN, Riboflavin) | Soluble Redox Mediator | Accelerating electron transfer from outer membrane cytochromes to electrodes in Shewanella studies [18]. |

| Polyoxometalate (POM) Clusters | Inorganic Support for Single-Atom Catalysts | Providing a tunable platform for anchoring transition metals for HER studies [21]. |

| Carbon Electrodes (e.g., POCO Graphite) | Working Electrode for Voltammetry | Serving as an electron acceptor for studying direct electron transfer from bacterial biofilms [18]. |

| Deuterated Solvents & Isotopically Labeled Metals (e.g., ^63^Cu, ^65^Cu) | Probes for Self-Exchange Reactions | Tracing electron self-exchange in metalloproteins via NMR or EPR [17]. |

The systematic evaluation of electron transfer kinetics, catalytic turnover, and thermodynamic stability provides a comprehensive picture of redox protein efficiency. As demonstrated, techniques like voltammetry and DFT simulations provide robust, quantitative data for comparing native and engineered systems. The continued refinement of these metrics, coupled with emerging tools like machine learning potentials [22], will undoubtedly accelerate the design of superior biocatalysts. For researchers in drug development and beyond, adhering to this standardized framework of metrics and protocols ensures a critical and objective assessment of performance, driving innovation in biomedical and bioenergy applications.

The Designer's Toolkit: Modern Strategies for Engineering Redox Proteins

The efficiency of engineered versus native redox proteins is a pivotal research area in biotechnology and drug development. Redox proteins, essential for electron transfer processes in cellular metabolism, are prime targets for engineering to enhance their stability, activity, and specificity for industrial and therapeutic applications. Accurately predicting protein structures and redox potentials is fundamental to this endeavor. AlphaFold has revolutionized protein structure prediction, while machine learning (ML) models are transforming the prediction of electrochemical properties like redox potentials. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these computational powerhouses, detailing their performance, protocols, and applications to empower researchers in evaluating and designing advanced redox proteins.

AlphaFold: Performance and Limitations in Protein Structure Prediction

Performance Analysis and Comparison

AlphaFold2 (AF2) represents a breakthrough in predicting protein tertiary structures, achieving accuracy comparable to experimental methods for many targets. However, systematic evaluations reveal specific strengths and weaknesses, particularly regarding its application to redox protein engineering.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AlphaFold2 and Related Structure Prediction Tools

| Method | Key Function | Performance Metric | Result | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) | Protein monomer structure prediction | Global RMSD vs. Native | Near-experimental for many singles [23] | Poor multi-domain orientation; single static conformation [24] [23] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Protein complex structure prediction | TM-score on CASP15 targets | Baseline for complexes [25] | Lower accuracy than AF2 for monomers [25] |

| AlphaFold3 (AF3) | Biomolecular structure prediction | TM-score on CASP15 targets | 10.3% lower than DeepSCFold [25] | - |

| Distance-AF | AF2 enhancement with distance constraints | Average RMSD vs. Native | 4.22 Å (vs. 11.75 Å for AF2) [23] | Requires user-specified distance constraints [23] |

| DeepSCFold | Protein complex structure prediction | TM-score on CASP15 targets | 11.6% higher than AlphaFold-Multimer [25] | Relies on sequence-derived structural complementarity [25] |

AF2 demonstrates remarkable accuracy in predicting stable protein conformations, with high stereochemical quality. It also excels at predicting local structural features, such as secondary structure (Q3 accuracy of 0.928) and solvent accessibility (Pearson Correlation Coefficient of 0.815) [26]. Nevertheless, for nuclear receptors—a class of proteins relevant to redox biology—AF2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average and shows limited capacity in capturing conformational diversity, particularly in homodimeric receptors where it misses functionally important asymmetry [24]. This is critical for redox protein engineering, as the binding pocket geometry is directly linked to function.

For protein complexes, AlphaFold-Multimer and AF3 face challenges. DeepSCFold, a method that uses sequence-derived structure complementarity to construct paired multiple sequence alignments, has been shown to outperform them, notably improving the prediction success rate for antibody-antigen binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AF3, respectively [25]. This is particularly relevant for studying redox protein interactions with their partners.

Experimental Protocol for AlphaFold-Based Structure Prediction

A standard workflow for predicting a protein structure using AlphaFold2 is as follows:

- Input Sequence Preparation: Obtain the amino acid sequence of the target protein.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Construction: Search genomic and metagenomic databases (e.g., UniRef, BFD, MGnify) for homologous sequences using tools like HHblits or Jackhmmer. This step provides the co-evolutionary information critical for AF2's accuracy.

- Template Identification (Optional): Identify known experimental structures (e.g., from the PDB) that are homologous to the target for use as structural templates.

- Structure Inference: Run the AF2 model using the MSA and template information. The Evoformer network processes the MSA and pair representations, followed by the structure module that iteratively refines the atomic coordinates.

- Model Generation and Ranking: AF2 typically generates five models. Each model is associated with a predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) score per residue (indicating local confidence) and a predicted template modeling (pTMs) score for the overall model quality.

For specific challenges, advanced protocols are used:

- Improving Domain Orientation with Distance-AF: When AF2 produces an incorrect multi-domain arrangement, Distance-AF can be employed. Users provide a set of distance constraints (e.g., 6-10 pairs of Cα atoms between domains, derived from experimental data or biological hypotheses). The method integrates these constraints as an additional loss term during the structure module's optimization, iteratively updating the network to satisfy the distances while maintaining proper protein geometry [23].

- Predicting Protein Complexes with DeepSCFold: The protocol starts by generating monomeric MSAs for each subunit. Then, two deep learning models are used: one predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score), and the other estimates interaction probability (pIA-score). These scores guide the systematic pairing of sequences across subunit MSAs to build deep paired MSAs. Finally, these paired MSAs are fed into AlphaFold-Multimer for complex structure prediction [25].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps for structure prediction using these AI tools:

Machine Learning for Redox Potential Prediction

Performance Analysis and Comparison of ML Methods

Accurately predicting redox potentials is crucial for designing redox flow batteries and engineering redox proteins. While first-principles methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) are used, they are computationally expensive and can have significant errors (~0.5 V). Machine learning offers a faster, efficient alternative [27] [28].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Redox Potential Prediction Methods

| Method | Principle | Best Reported MAE | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Quantum chemistry calculation | ~0.5 V (typical error) [28] | Provides fundamental electronic insights | High computational cost; accuracy depends on functional [27] [28] |

| ML-aided First-Principles [28] | ML force fields for thermodynamic integration | ~0.1 V (for Ag, Cu, Fe couples) | High accuracy on absolute scale; uses hybrid functionals | Complex multi-step workflow; computationally intensive |

| Graph-Based GPR [27] | Gaussian Process Regression on molecular graphs | Not specified | Fast prediction; uses largest experimental ORFB database | Performance depends on quality/scope of experimental data |

| Graph Neural Networks [29] | Graph-based ML on ORedOx159 dataset | 5.6 kcal mol⁻¹ (~0.24 V) [29] | Good accuracy with instant descriptors; uses homogeneous DFT dataset | Limited to organic compounds in the dataset |

ML models significantly accelerate the screening of organic molecules for redox flow batteries. For instance, graph-based Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) models have been developed using a comprehensive database of over 500 experimental redox potential measurements from hundreds of publications, which is the largest such database for organic redox flow batteries (ORFBs) [27]. Another study established the ORedOx159 database, containing 318 one-electron reduction and oxidation reactions for 159 large organic compounds, and demonstrated that graph-based ML methods can achieve high predictive accuracy with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 5.6 kcal mol⁻¹ (approximately 0.24 V) using instantaneously computed descriptors [29].

For the highest accuracy, a hybrid approach combining ML and first-principles calculations is emerging. One method uses ML force fields to perform extensive statistical sampling via thermodynamic integration from the oxidized to the reduced state. The accuracy is then refined step-by-step using Δ-machine learning to shift from semi-local to hybrid density functionals. This approach predicted the redox potentials of Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺, Cu²⁺/Cu⁺, and Ag²⁺/Ag⁺ to be 0.92 V, 0.26 V, and 1.99 V, respectively, which are in good agreement with the best experimental estimates (0.77 V, 0.15 V, and 1.98 V) [28].

Experimental Protocol for ML-Based Redox Potential Prediction

A generalized workflow for developing and applying an ML model to predict redox potentials is outlined below.

Data Curation and Database Construction:

- Source Experimental/DFT Data: Collect redox potential values from literature or perform DFT calculations. Critical metadata includes molecular structure, pH, solvent type, and reference electrode [27] [29].

- Standardize Data: Convert all redox potentials to a common reference (e.g., Standard Hydrogen Electrode, SHE).

- Create a Database: Compile the data into a structured, machine-readable format. Examples include the ORedOx159 database (with DFT-calculated values) [29] and the comprehensive experimental ORFB database [27].

Molecular Representation and Feature Engineering:

- Convert molecular structures into numerical representations. Common methods include:

- Graph Representations: Represent molecules as graphs where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. This is used in Graph Neural Networks and graph-kernel GPR models [27] [29].

- Chemical Descriptors: Calculate specific molecular features like topological indices, electronic properties, or functional group counts.

- Convert molecular structures into numerical representations. Common methods include:

Model Training and Validation:

- Split Data: Partition the database into training, validation, and test sets.

- Select ML Algorithm: Choose a suitable algorithm (e.g., Gaussian Process Regression, Graph Neural Networks, Random Forest).

- Train Model: The model learns the complex relationship between the molecular representation/features and the target redox potential.

- Validate and Test: Assess model performance on the held-out validation and test sets using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC).

Prediction and Deployment:

- Use the trained model to predict the redox potential of novel, unscreened molecules.

The following diagram visualizes the core workflow for machine learning-based redox potential prediction:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Protein and Redox Research

| Item/Reagent | Function/Application | Relevance in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database | Repository of pre-computed protein structure predictions. | Provides instant access to ~200 million AF2 models for initial analysis, saving computational resources [26]. |

| ORedOx159 Database | A homogeneous, DFT-calculated database of redox potentials for 159 organic compounds. | Serves as a benchmark dataset for training and testing ML models for redox potential prediction [29]. |

| Experimental ORFB Database | A comprehensive collection of over 500 experimental redox potential measurements. | Enables training of ML models like graph-based GPR on real-world experimental data for ORFB applications [27]. |

| Distance Constraint File | A user-generated file specifying target distances between Cα atoms. | Essential input for Distance-AF to guide AF2 towards a desired conformation, e.g., from cryo-EM or NMR data [23]. |

| Paired Multiple Sequence Alignment (pMSA) | A curated MSA that pairs homologous sequences from interacting protein chains. | Critical input for accurate protein complex prediction using methods like DeepSCFold and AlphaFold-Multimer [25]. |

| Hybrid Density Functional (e.g., PBE0) | A more accurate class of functionals for quantum chemical calculations. | Used in high-accuracy, ML-aided first-principles calculations to achieve redox potential predictions with errors of ~0.1 V [28]. |

In the pursuit of efficient biocatalysts and therapeutics, rational and semi-rational design strategies have evolved beyond targeting merely the primary active site. The focus has expanded to encompass the second coordination sphere—the intricate network of amino acid residues and structural elements surrounding the catalytic core that profoundly influence substrate access, catalytic efficiency, and inhibitor specificity. This paradigm shift is particularly transformative in redox protein engineering, where mimicking the sophisticated environment of native enzymes is crucial for achieving high performance in artificial systems. The integration of these design principles is accelerating the development of novel biocatalysts for demanding applications, including drug discovery and biosensing, by providing engineered proteins and bioinspired catalysts that bridge the efficiency gap between natural and artificial systems [30] [31] [32].

This guide objectively compares the performance of native redox proteins against their engineered counterparts—ranging from single-point mutants to advanced nanozymes—by examining key experimental data on their catalytic efficiency, binding affinity, and inhibitory specificity. The evaluation is framed within a broader thesis on advancing redox protein efficiency, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured comparison of these systems' capabilities and limitations.

Performance Comparison: Engineered vs. Native Systems

The following tables summarize quantitative data comparing the performance of native enzymes, engineered enzymes, and nanozymes, highlighting the impact of rational and semi-rational design on key catalytic parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Native, Engineered, and Nanozyme Systems

| System Type | Catalytic Activity / Efficiency | Binding Affinity (Kₘ or Kᵢ) | Inhibitor Specificity / Applications | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native Thyroid Peroxidase | Native reference activity | Native reference affinity | Specifically inhibited by antithyroid drugs [30] | Heme cofactor with specific amino acid pocket [30] |

| CuNC Nanozyme (Baseline) | Specific activity: 47.82 M⁻¹ min⁻¹ per Cu site [30] | Kₘ(H₂O₂): 69.36 mM [30] | Lacks specificity of native enzymes [30] [31] | Atomically dispersed Cu-N₄ sites [30] [31] |

| CuNC-OH Nanozyme (Engineered) | Specific activity: 343.92 M⁻¹ min⁻¹ per Cu site (7.19x increase over CuNC) [30] | Kₘ(H₂O₂): 41.30 mM (superior H₂O₂ affinity) [30] | Specific inhibition by antithyroid drugs; used for drug screening [30] [31] | Cu-N₄ sites with proximal -OH groups mimicking enzyme pocket [30] [31] |

| Engineered Promiscuous Enzymes | Secondary activity often low, enhanced via directed evolution [32] | Altered substrate scope and binding modes [32] | Basis for evolving new enzymatic functions [32] | Modified active site, access tunnels, and dynamics [32] |

Table 2: Impact of Second-Sphere Engineering on Catalytic Parameters

| Engineering Strategy | Target System | Experimental Outcome | Key Technique for Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction of Proximal -OH Groups | CuNC-OH Nanozyme | 7.19x increase in specific activity; lowered Kₘ for H₂O₂; enabled specific drug inhibition [30] [31] | XPS, FTIR, EXAFS, In-situ ATR-FTIR [30] [31] |

| Modulating Conformational Dynamics | Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) | Regulation of interdomain electron transfer (IET) rates for efficient NO production [33] | Laser flash photolysis, qXL-MS, Site-specific IR spectroscopy [33] |

| Active Site and Access Tunnel Engineering | Cytochrome P450s & other promiscuous enzymes | Catalysis of non-native reactions (e.g., C-H amination, cyclopropanation) [32] | MD simulations, QM/MM calculations, Directed Evolution [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Design and Inhibition Assay of Second-Sphere Nanozymes

Objective: To synthesize a nanozyme with a engineered second coordination sphere and evaluate its peroxidase-like activity and inhibition profile for antithyroid drug screening [30] [31].

Synthesis of CuNC-OH Nanozyme:

- Materials: Cu(NO₃)₂, o-phenylenediamine (OPD), KCl template, methanol, nitrogen gas, ultrapure water, sulfuric acid, oxidative nitric acid [30] [31].

- Method: A salt-template strategy is employed. Cu(NO₃)₂, OPD, and KCl are mixed in methanol and dried. The powder is annealed under nitrogen flow. The KCl template is removed with water, and aggregated Cu species are etched with H₂SO₄ to yield CuNC. Finally, treatment with oxidative nitric acid introduces proximal hydroxyl groups, producing CuNC-OH [30] [31].

Structural Characterization:

Activity and Inhibition Kinetics:

- Activity Assay: Peroxidase-like activity is quantified using a colorimetric assay with H₂O₂ and 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB). The oxidation of TMB is monitored by measuring the absorbance at 652 nm [30] [31].

- Kinetic Analysis: Michaelis-Menten kinetics are determined by varying H₂O₂ concentration to calculate Kₘ and specific activity [30].

- Inhibition Assay: The inhibition efficiency (%)(I) is calculated using the formula: I (%) = (A₀ - A)/A₀ × 100%, where A₀ and A are the absorbance values at 652 nm in the absence and presence of the inhibitor, respectively. Dose-response curves are generated to analyze inhibition features of different antithyroid drugs [30].

Investigating Interdomain Electron Transfer in Native Redox Proteins

Objective: To measure the rate of a critical interdomain electron transfer (IET) step within a multidomain redox enzyme, Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS), and understand how dynamics regulate this process [33].

Sample Preparation:

Laser Flash Photolysis:

Data Analysis:

- The observed change in absorbance is fitted to a kinetic model to determine the IET rate constant. This rate directly reports on the efficiency of forming the ET-competent docked state between the FMN and heme domains [33].

- The experiment can be repeated with site-specific mutants, in the absence of CaM, or with ligands to investigate how these factors alter conformational dynamics and IET rates [33].

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Electron Transfer in a Multidomain Redox Enzyme

Second-Sphere Nanozyme Engineering Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Redox Protein Design and Analysis

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| o-Phenylenediamine (OPD) | Nitrogen-rich precursor for creating M-Nₓ sites in carbon supports [30] [31] | Synthesis of CuNC and CuNC-OH nanozymes [30] [31] |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Salt template for forming ultrathin nanosheet structures during synthesis [30] [31] | Morphology control in CuNC-based nanozymes [30] [31] |

| 3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) | Chromogenic substrate for colorimetric detection of peroxidase-like activity [30] [31] | Quantifying H₂O₂ activation and kinetics in nanozyme assays [30] [31] |

| Calmodulin (CaM) with Ca²⁺ | Regulatory protein that activates electron transfer in NOS by binding to a linker region [33] | Studying conformational control of IET in native NOS enzymes [33] |

| 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) | Spin-trapping agent for detecting and identifying short-lived radical intermediates [30] | EPR spectroscopy to probe catalytic mechanism (e.g., •OH formation) [30] |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Method for validating direct drug-target engagement in physiologically relevant environments (cells, tissues) [34] | Confirming compound binding to intended target in native cellular context [34] |

Directed Evolution and High-Throughput Screening for Enhanced Activity

Directed evolution has emerged as a powerful protein engineering strategy for generating enzymes with enhanced properties, including catalytic activity, substrate specificity, thermostability, and organic solvent resistance [35]. This approach mimics natural evolution in laboratory settings through iterative rounds of mutagenesis and selection, requiring high-throughput screening (HTS) or selection methods to identify improved variants from vast mutant libraries [35]. The evaluation of engineered versus native redox protein efficiency represents a critical research frontier, particularly given that oxidoreductases and metalloproteins constitute approximately one-third of all known proteins and serve as essential catalysts in fundamental biological processes including photosynthesis, respiration, metabolism, and molecular signaling [3].

While natural redox proteins have evolved to function within specific physiological contexts, their native properties often fall short of the requirements for industrial applications, biosensing, or therapeutic interventions. Directed evolution addresses these limitations by enabling the development of engineered redox proteins with manipulated redox potentials, increased electron-transfer efficiency, and expanded catalytic capabilities beyond their native functions [3]. This comparative analysis examines the methodologies, experimental data, and technological advances that enable rigorous evaluation of engineered redox proteins against their native counterparts, with particular emphasis on high-throughput screening strategies that accelerate this optimization process.

High-Throughput Screening and Selection Methodologies

The effectiveness of directed evolution campaigns depends critically on the availability of robust screening or selection methods capable of efficiently interrogating genetic diversity. Screening involves evaluating individual variants for desired properties, while selection automatically eliminates nonfunctional variants through selective pressure [35]. The following sections detail the primary HTS methodologies employed in directed evolution of redox proteins.

Main Screening Platforms

Table 1: High-Throughput Screening Methods for Directed Evolution

| Method | Throughput | Key Features | Applications in Redox Protein Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | 10²-10⁴ variants | Compatibility with colorimetric/fluorometric assays; amenability to automation [35] | Enzyme activity assays using UV-vis absorbance or fluorescence detection; monitoring cell growth and substrate conversion [35] |

| Digital Imaging (DI) | >10⁴ colonies | Solid-phase screening of colonies; uses colorimetric assays [35] | Screening transglycosidase variants; identifying mutants with altered hydrolytic/transferase activity ratios [35] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Up to 30,000 cells/second | Based on fluorescent signals of individual cells; enables ultra-high-throughput screening [35] | GFP-reporter assays; product entrapment; cell surface display systems [35] |

| Droplet Microfluidics | >10⁶ variants | Picoliter compartments; shorter time and higher sensitivity than standard assays [35] [36] | Screening α1,2-fucosyltransferase variants via whole-cell biosensors; in vitro compartmentalization [36] |

Selection and Display Technologies

Selection methods differ fundamentally from screening approaches by applying selective pressure to directly eliminate unwanted variants, enabling assessment of extremely large libraries (exceeding 10¹¹ members) [35]. Key selection technologies include:

Cell Surface Display: Fusion proteins are anchored to the outer surface of cells (bacteria, yeast, or mammalian), where they interact directly with external substrates [35]. This technology has been successfully integrated with FACS, achieving remarkable enrichment efficiencies—up to 6,000-fold for active clones after a single screening round in one reported bond-forming enzyme evolution study [35].

In Vitro Compartmentalization (IVTC): This approach utilizes water-in-oil emulsion droplets to isolate individual DNA molecules, creating independent microreactors for cell-free protein synthesis and enzyme reactions [35]. IVTC circumvents cellular regulatory networks and transformation efficiency limitations, making it particularly valuable for oxygen-sensitive enzymes like [FeFe] hydrogenase [35].

Plasmid Display: This technology physically links translated proteins to their encoding genes, making protein libraries accessible to external selective pressures while maintaining genotype-phenotype linkage for subsequent gene amplification [35].

Diagram 1: HTS and selection workflows for engineering redox proteins. The diagram illustrates parallel screening and selection approaches applied to mutant libraries, culminating in engineered redox proteins with enhanced properties.

Experimental Data: Engineered vs. Native Redox Protein Performance

Quantitative comparison of engineered and native redox proteins reveals significant enhancements achievable through directed evolution. The following experimental data, compiled from recent studies, demonstrates the efficacy of these approaches across various enzyme classes and targeted properties.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Native vs. Engineered Redox Proteins

| Enzyme / Protein | Native Property | Engineered Property | Enhancement Factor | Method Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FutC α1,2-Fucosyltransferase [36] | Catalytic efficiency: 2.177 ± 0.335 min⁻¹ mM⁻¹ | Catalytic efficiency: 5.024 ± 0.702 min⁻¹ mM⁻¹ | 2.31-fold | Whole-cell biosensor + droplet microfluidics |

| Glycosyltransferase [35] | Baseline activity on fluorescent substrates | Enhanced activity using fluorescent substrates | >400-fold | FACS with product entrapment |

| β-Galactosidase [35] | Wild-type kcat/KM | Improved kcat/KM for selected mutants | 300-fold higher than wild-type | IVTC with W/O/W emulsion droplets |

| Transglycosidase [35] | Native transglycosidase/hydrolysis ratio | Improved activity ratio | 70-fold improvement | Digital Imaging screening |

| OmpT Protease [35] | Baseline activity | Enriched active clones | 5,000-fold enrichment after one round | FRET-based assay with FACS |

Case Study: α1,2-Fucosyltransferase Engineering

A recent landmark study demonstrates the power of integrated screening platforms for enhancing redox enzyme efficiency [36]. Researchers developed a whole-cell biosensor coupled with droplet microfluidics to screen α1,2-fucosyltransferase (FutC) variants for improved 2'-fucosyllactose (2'-FL) synthesis. The experimental protocol consisted of:

Biosensor Design: Construction of a whole-cell biosensor that translates 2'-FL concentration into a positively correlated fluorescence signal using the native lac operon system [36].

Interference Elimination: Implementation of a thermosensitive lactose-degradation pathway to eliminate substrate interference, a critical innovation that addressed specificity limitations in prior screening methods [36].

Droplet Microfluidics: Encapsulation of mutant libraries in picoliter droplets, enabling ultra-high-throughput screening at a scale approximately 1000-fold greater than microtiter plate-based methods [36].

Sorting and Validation: Fluorescence-activated sorting of droplets followed by validation of selected variants through shake-flask fermentation and enzymatic assays [36].

This approach identified variant M1 (V93I) with a catalytic efficiency (5.024 ± 0.702 min⁻¹ mM⁻¹) 2.31 times greater than native FutC, while also reducing byproduct formation—a critical advance for industrial-scale production of 2'-FL [36].

Redox Potential Engineering in Metalloproteins

Iron-sulfur (Fe-S) proteins represent another prominent class of redox enzymes that have been successfully engineered through directed evolution approaches. These proteins mediate electron transfer in biological processes ranging from energy conversion and respiration to DNA repair and redox signaling [1]. Recent advances in machine learning, such as the FeS-RedPred framework, now enable accurate prediction of redox potentials in Fe-S proteins with a mean absolute error of approximately 40 mV, approaching the accuracy of sophisticated computational methods while offering significantly higher throughput [1].

Protein engineering strategies have successfully manipulated redox potentials in various metalloprotein classes:

Heme Proteins: Engineering of cytochrome P450 enzymes has enabled manipulation of their redox potentials for enhanced coupling efficiency and expanded substrate range [3].

Iron-Sulfur Proteins: Directed evolution of [2Fe-2S] clusters in ferredoxins, Rieske, and mitoNEET-type proteins has yielded variants with finely tuned reduction potentials optimized for specific electron transfer chains [1].

Copper Proteins: Blue copper proteins have been engineered with altered redox potentials through rational design of their metal coordination environments, demonstrating the interplay between geometric structure and electronic properties [3].

Experimental Protocols for Redox Protein Evaluation

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for rigorous comparison between engineered and native redox proteins. This section details key methodologies cited in the literature.

Purpose: To enable ultra-high-throughput screening of glycosyltransferase activity in picoliter droplets.

Procedure:

- Clone the gene encoding AfcA 1,2-α-L-fucosidase from Bifidobacterium bifidum into a biosensor strain.

- Integrate the 2'-FL catabolic pathway from E. coli O126 into the genome to enable specific detection.

- Introduce a thermosensitive lactose-degradation pathway (using λ-red homologous recombination) to eliminate interference from substrate lactose.

- Construct mutant libraries of the target enzyme (e.g., FutC) via random mutagenesis.

- Perform droplet microfluidics: co-encapsulate enzyme variants, substrates, and biosensor cells in water-in-oil emulsion droplets.

- Incubate droplets to allow enzymatic reaction and biosensor activation.

- Sort droplets based on fluorescence intensity using FACS.

- Recover sorted variants for validation in microtiter plates and shake-flask fermentation.

Key Reagents:

- M9 medium supplemented with yeast extract, tryptone, and glycerin

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium for routine cultivation

- Fluorescent reporter protein (SFGFP)

Purpose: To screen intracellular enzyme activity based on differential transport of fluorescent substrates versus products.

Procedure:

- Generate mutant library and express in appropriate host cells.

- Incubate cells with fluorescent substrate that can freely cross cell membranes.

- Allow enzymatic conversion to product that is retained within cells due to size, polarity, or chemical properties.

- Wash cells to remove external substrate and any fluorescent product that has leaked out.

- Analyze and sort cells based on intracellular fluorescence using FACS.

- Collect highest-fluorescence populations for plasmid recovery and subsequent rounds of evolution.

Applications: Successfully applied to engineer glycosyl-transferase with >400-fold enhanced activity for fluorescent selection substrates [35].

Purpose: To screen enzyme variants under controlled conditions independent of cellular regulation.

Procedure:

- Generate mutant library and link to reporter system (e.g., fluorescent product capture on microbeads).

- Emulsify DNA library in water-in-oil emulsion to create discrete compartments.

- Perform in vitro transcription/translation within compartments.

- Allow enzymatic reaction to proceed, generating fluorescent products.

- For microbead-based systems: couple enzymes to antibody-coated microbeads; for droplet systems: sort directly using FACS.

- Isolate fluorescent compartments/beads and recover encoding DNA.

Applications: Enabled identification of β-galactosidase mutants with 300-fold higher kcat/KM values than wild-type enzyme [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Directed Evolution of Redox Proteins

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates (96-well to 9600-well) | Miniaturized reaction vessels for parallel screening | Colorimetric/fluorometric enzyme assays; cell growth profiling [35] |

| Fluorescent Proteins (GFP, YFP, CFP, RFP) | Reporter genes for biosensors; FRET donors/acceptors | Coupling target enzyme activity with fluorescence output [35] |

| Droplet Microfluidics Device | Generation and manipulation of picoliter emulsion droplets | Ultra-high-throughput screening with >10⁶ variants [35] [36] |

| Water-in-Oil Emulsion Reagents | Compartmentalization for IVTC | Creating isolated reaction environments for cell-free systems [35] |

| Whole-Cell Biosensor Strains | Linking product concentration to detectable signal | Specific detection of target metabolites like 2'-FL [36] |

| FACS Instrumentation | High-speed sorting based on fluorescence | Screening cell surface display libraries; product entrapment assays [35] |

| Surface Display Scaffolds | Anchoring motifs for protein presentation | Yeast, bacterial, or mammalian cell surface display of enzyme libraries [35] |