Strategies to Combat Non-Specific Adsorption in Redox Biosensors: From Antifouling Materials to Clinical Validation

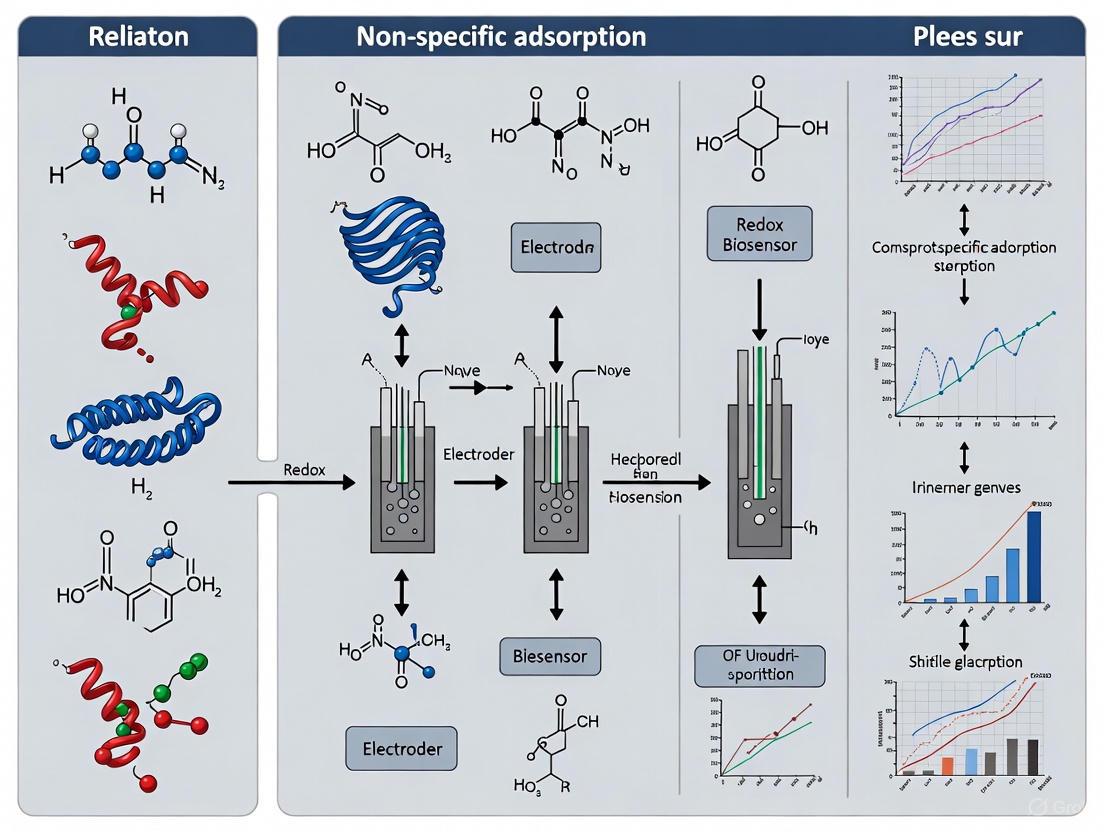

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) remains a critical barrier to the reliability and widespread adoption of redox biosensors in complex biological samples like blood, serum, and milk.

Strategies to Combat Non-Specific Adsorption in Redox Biosensors: From Antifouling Materials to Clinical Validation

Abstract

Non-specific adsorption (NSA) remains a critical barrier to the reliability and widespread adoption of redox biosensors in complex biological samples like blood, serum, and milk. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational mechanisms of NSA and its impact on signal integrity. It delves into the latest methodological advances, including novel antifouling coatings, genetically encoded sensors, and material innovations like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that enhance electron transfer. The content also addresses practical troubleshooting and optimization protocols for minimizing fouling, and concludes with rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of biosensor performance against conventional assays, highlighting pathways toward robust clinical and point-of-care applications.

Understanding the Redox Biosensor Landscape and the Fouling Challenge

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA) and why is it a critical issue in biosensing? Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA) refers to the undesired, random adhesion of atoms, ions, or molecules (like proteins, cells, or other biomolecules) to a biosensor's surface through physical or chemical interactions [1]. It is a primary form of biofouling that critically compromises biosensor performance by:

- Reducing Sensitivity and Selectivity: NSA creates a high background signal that can mask the specific signal from the target analyte, raising the limit of detection and causing false positives [1] [2].

- Impairing Reproducibility: Inconsistent fouling across sensor surfaces leads to unreliable and variable results [1].

- Causing Signal Drift: The continuous accumulation of non-specifically bound molecules can lead to a drifting baseline, complicating data interpretation over time [2].

- Blocking Bioreceptors: NSA can physically block biorecognition elements (like antibodies or aptamers) from binding to their target, potentially causing false negatives [2].

2. What are the primary mechanisms driving NSA? NSA is primarily driven by physisorption (physical adsorption), which involves weaker intermolecular forces, as opposed to stronger covalent bonding in chemisorption [1]. The main interactions facilitating NSA are [2]:

- Hydrophobic Interactions

- Electrostatic (Ionic) Interactions

- Hydrogen Bonding

- van der Waals Forces

The following diagram illustrates how these forces contribute to the fouling of a biosensor interface.

3. How does sample complexity influence NSA? The impact of NSA is directly proportional to the complexity of the sample matrix. Complex biological fluids contain high concentrations of interfering proteins and other biomolecules that readily adsorb to surfaces [3].

- Cell Culture Media: 1-10 mg/mL of non-specific proteins [3].

- Crude Cell Lysate: 30-60 mg/mL of proteins [3].

- Serum: 40-80 mg/mL of proteins [3]. This high concentration of interferents is why biosensor performance validation in real samples, not just buffer, is essential for clinical translation [4].

4. What strategies exist to minimize or prevent NSA? Strategies to combat NSA are broadly classified into two categories [1]:

- Passive Methods (Surface Coatings): Aim to prevent adsorption by creating a physical, inert barrier on the sensor surface.

- Active Methods (Removal Techniques): Dynamically remove adsorbed molecules after formation, often using transducers (electromechanical, acoustic) or fluid dynamics.

5. Are there biosensor designs or detection methods less susceptible to NSA? Some detection methods can distinguish specific binding from NSA. For instance, Attenuated Total Internal Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy and ellipsometry have been used to differentiate specific binding signals from background NSA [1]. Furthermore, integrating microfluidic systems can help lower non-specific adsorption and cross-reactivity by controlling fluid flow and generating shear forces that sweep away weakly adhered molecules [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common NSA Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: High Background Signal in Complex Samples

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background noise or signal drift when testing serum, blood, or cell lysate samples. | Sample matrix proteins (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins) adsorbing to sticky sensor surface. | Apply an antifouling surface coating to create a bioinert barrier. | Coatings form a hydrated, neutral layer that minimizes intermolecular interactions with foulants [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Functionalizing a Surface with a Zwitterionic Peptide Coating Zwitterionic peptides are a modern, high-performance alternative to traditional PEG coatings [6].

- Surface Preparation: Clean the sensor surface (e.g., gold, silicon) rigorously. For a gold surface, a standard piranha clean or oxygen plasma treatment is often used.

- Peptide Solution Preparation: Dissolve the zwitterionic peptide (e.g., sequence EKEKEKEKEKGGC) in a suitable buffer like ultrapure water or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a concentration of 0.1-1.0 mg/mL [6].

- Immobilization: Incubate the clean sensor surface with the peptide solution for several hours at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. The terminal cysteine residue facilitates covalent attachment to gold via thiol-gold chemistry [6] [3].

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the functionalized surface with buffer and ultrapure water to remove any physisorbed peptides.

- Validation: Validate the coating's efficacy by exposing it to a complex solution like 10% serum and measuring the adsorbed mass versus an uncoated surface using a technique like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM).

Problem 2: Loss of Sensitivity and Signal Over Time

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor signal degrades or drifts during prolonged operation or between measurement cycles. | Progressive fouling passivates the surface and/or degrades the coating. | Implement an active removal strategy or use a resettable sensor. | Applying external energy or altering surface properties shears away weakly adsorbed molecules [1] [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: In Situ Electrical Resetting of a FET Biosensor This protocol outlines a method to regenerate a sensor surface electronically [5].

- Sensor Design: Fabricate a field-effect transistor (FET) biosensor, for example, using a semiconducting carbon nanotube (CNT) film and functionalize it with pH-sensitive aptamer probes.

- Target Capture & Measurement: Expose the biosensor to the sample containing the target analyte and record the signal.

- Electrical Reset: Apply a specific potential to on-chip palladium electrodes to induce local pH changes. This rapid pH swing denatures the aptamer-target complex and disrupts the bonds of adsorbed molecules, releasing them from the sensor surface [5].

- Sensor Recovery: Remove the applied potential, allowing the local pH to return to baseline and the aptamer probes to refold into their native, active state.

- Reuse: The sensor can now be reused for a new measurement. This cycle has been demonstrated to work effectively for over ten reuse cycles [5].

The workflow for this active resetting process is shown below.

Problem 3: Non-Specific Binding in Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| MIP-based sensors show interference from molecules structurally similar to the target. | Functional groups on the MIP surface outside the imprinted cavities bind molecules non-specifically. | Post-synthesis modification with surfactants to block non-specific sites [7]. | Surfactants interact with and neutralize external functional groups without affecting the tailored cavities [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Surfactant Modification of MIPs to Suppress NSA

- MIP Synthesis: Synthesize the MIP using standard bulk or precipitation polymerization with your target analyte as the template (e.g., sulfamethoxazole, SMX). Create a non-imprinted polymer (NIP) as a control [7].

- Surfactant Selection: Choose a surfactant with a charge opposite to your MIP's external functional groups.

- Modification Process: Incubate the synthesized and washed MIP particles with a solution of the selected surfactant (e.g., 1-5 mM) for a defined period.

- Washing: Wash the MIPs thoroughly to remove any unbound surfactant.

- Validation: Confirm the reduction in NSA by comparing the binding of the target analyte to the MIP and NIP before and after surfactant treatment using binding isotherms [7].

Quantitative Data on Antifouling Coating Performance

The following table summarizes the non-specific adsorption performance of various surface coatings, a critical consideration for selecting the right material for your biosensor.

Table 1: Comparison of Antifouling Coating Performance in Complex Media

| Coating Material | Type | Test Medium | Non-Specific Adsorption Level | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afficoat (Zwitterionic Peptide) | Self-assembled monolayer | Bovine Serum (76 mg/mL protein) | Lowest (Outperformed PEG & CM-Dextran) | Superior antifouling, allows protein immobilization | [3] |

| Zwitterionic Peptide (EKEKEKEK) | Self-assembled monolayer | GI Fluid, Bacterial Lysate | >10x improvement in S/N ratio vs. PEG | Broad-spectrum protection vs. proteins & cells | [6] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer Brush | Serum | Moderate (Baseline for comparison) | "Gold standard", well-characterized | [1] [6] |

| PSS / TSPP Film | Negatively charged layer | Buffer (for QD adsorption) | Reduced QD adsorption by 300-400 fold | Simple layer-by-layer self-assembly on glass | [8] |

| Cross-linked Protein Films | Physical/Blocking | Complex Matrices | Effective for many applications | Low cost, easy to apply (e.g., BSA, Casein) | [1] [2] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for NSA Reduction

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for NSA Reduction Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in NSA Reduction | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Zwitterionic Peptides (e.g., EKEKEKEKEKGGC) | Forms a dense, charge-neutral hydration layer that acts as a physical and energetic barrier to biomolecular adsorption [6]. | Covalent immobilization on gold or PSi surfaces for ultralow fouling biosensors [6] [3]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A traditional polymer coating that binds water via hydrogen bonding, creating a steric and energetic barrier to protein adsorption [1]. | Grafting to surfaces as a polymer brush to resist protein fouling; often used as a benchmark [1] [6]. |

| Blocking Proteins (BSA, Casein) | Physically adsorbs to uncovered, "sticky" sites on the sensor surface, preventing subsequent non-specific binding of sample proteins [1]. | Used as a blocking step in ELISA-style assays and many commercial biosensor kits [1]. |

| Surfactants (SDS, CTAB) | Ionic surfactants can neutralize charged functional groups on material surfaces (e.g., MIPs) that are responsible for non-specific electrostatic binding [7]. | Post-synthesis treatment of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) to improve selectivity [7]. |

| Negatively Charged Polymers (PSS, TSPP) | Creates a dense, charged film that electrostatically repels negatively charged probe molecules (e.g., certain QDs), reducing their non-specific adsorption [8]. | Layer-by-layer self-assembly on glass substrates to create a low-background surface for fluorescence-based assays [8]. |

| N-Methyl-DL-valine hydrochloride | N-Methyl-DL-valine hydrochloride, MF:C6H14ClNO2, MW:167.63 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-Cysteine hydrochloride | D-Cysteine Hydrochloride for Research Applications | Explore the research uses of D-Cysteine hydrochloride in cancer and neuroscience studies. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

In redox biosensing, the NADPH/NADP+ and glutathione (GSH/GSSG) couples form a critical metabolic partnership. NADPH serves as the primary reducing power, essential for maintaining glutathione in its reduced state (GSH), which in turn defends against oxidative stress and modulates redox signaling. This intricate relationship means that the performance of a redox biosensor is inevitably influenced by the dynamic equilibrium between these systems. Understanding this interplay is fundamental to troubleshooting experimental artifacts, particularly the challenge of non-specific adsorption and signal interference, to achieve precise and reliable measurements.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Redox Biosensing Challenges

FAQ 1: My biosensor shows an unexpected oxidation signal. How can I determine if this is a true biological response or non-specific interference?

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical interference from other reactive species (e.g., HOCl, peroxynitrite) [9]. | Test sensor response with specific oxidant generators and scavengers. Check if the signal is reversible by adding reducing agents like DTT. | Use more specific biosensors (e.g., roGFP2-Orp1 for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) and confirm results with complementary methods like HPLC [10] [9]. |

| pH sensitivity of the biosensor, as fluorescence can be pH-dependent [10] [11]. | Measure the pH of the cellular compartment or buffer simultaneously using a pH indicator. | Select pH-insensitive biosensors where possible (e.g., Grx1-roGFP2 is stable from pH 5.5-8.5) [9] or run parallel controls with a pH-only sensor [12]. |

| Sensor over-expression leading to buffering of the redox species and altered kinetics [13]. | Titrate the expression level of the biosensor (e.g., using weaker promoters or lower transfection doses). | Use the lowest possible biosensor expression level that still yields a measurable signal [10]. |

| Non-specific adsorption on sensor or vessel surfaces, altering local redox environment. | Include a non-binding control sensor (e.g., NAPstarC) [13] to establish baseline signal drift. | Use surface passivation agents (e.g., BSA, PEG) in assays and ensure the use of ratiometric sensors to correct for non-specific background [10]. |

FAQ 2: My NADPH biosensor (e.g., NAPstar) has a low signal-to-noise ratio. What steps can I take to improve the reading?

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low brightness of the biosensor, especially in small cellular compartments [14]. | Compare the in-cellulo fluorescence intensity to established benchmarks for that sensor. | Switch to a brighter, engineered biosensor variant, such as superfolder roGFP2 (sfroGFP2), which offers improved fluorescence intensity [14]. |

| Incorrect excitation/emission settings or photobleaching. | Perform a full excitation and emission scan on purified protein or a control sample. | Use ratiometric measurement to normalize for variations in sensor concentration and laser power [13] [10]. Employ FLIM (Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging) if possible, as it is less sensitive to concentration and intensity artifacts [13]. |

| Incompatible dynamic range for the biological system under study. | Challenge the system with known oxidants and reductants to see if it saturates. | Select a biosensor from a family with a suitable range. For example, the NAPstar family offers variants with different affinities (Kd(NADPH) from 0.9 to 11.6 µM) to match various NADPH/NADP+ ratios [13]. |

FAQ 3: How can I verify that my biosensor is specifically reporting on the NADPH/NADP+ couple and not equilibrating with the glutathione pool?

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Checks | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of specificity in the sensor's sensing domain. | Genetically or pharmacologically perturb the glutathione system (e.g., with BSO to deplete GSH) and observe the sensor response. Compare with a known glutathione-specific sensor (e.g., Grx1-roGFP2). | Use sensors engineered for high specificity. The NAPstar family was rationally designed from bacterial Rex domains to favor NADPH/NADP+ over NADH/NAD+, and shows substantially lower affinity for NADH [13]. |

| Endogenous glutaredoxin activity causing crosstalk between redox pools. | Use selective impairment of the glutathione and thioredoxin pathways [13]. | Express the biosensor in a defined compartment and use targeted inhibitors to dissect the contribution of individual antioxidative pathways [13] [15]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Specificity of a NADPH/NADP+ BiosensorIn Vitro

This protocol is crucial for establishing that your biosensor responds specifically to the NADP redox couple before moving to cellular experiments [13].

- Recombinant Protein Purification: Express and purify your biosensor (e.g., a NAPstar variant) as a recombinant protein.

- Fluorescence Titration:

- Prepare a series of buffers with a fixed total NADP pool (e.g., 150 µM NADP+) but varying the NADPH/NADP+ ratio (e.g., from 0.001 to 5).

- For each ratio, record the fluorescence excitation and emission spectra.

- Key Check: The sensor's ratiometric signal (e.g., TS/mCherry for NAPstars) should be dependent on the NADPH/NADP+ ratio and remain largely stable across different total NADP pool sizes. This confirms it reports the genuine redox state, not just concentration [13].

- Specificity Test: Repeat the titration using NADH/NAD+ at the same concentration ranges. A specific NADPH biosensor will have a much weaker affinity (higher Kd) for NADH [13].

Protocol 2: Measuring Compartment-Specific NADP Redox State in Live Cells

This protocol leverages the genetic encodability of modern biosensors to achieve subcellular resolution [13] [10].

- Construct Design: Clone your NADPH biosensor (e.g., NAPstar3) into an appropriate mammalian expression vector. Fuse it with a targeting sequence (e.g., a nuclear localization sequence, or a mitochondrial targeting sequence) to direct it to your organelle of interest [10].

- Cell Transfection: Transfect your target cells (e.g., HEK293, yeast) with the constructed plasmid. Use a low-expression promoter or titrate DNA to avoid buffering the redox state.

- Live-Cell Imaging:

- Image cells 24-48 hours post-transfection using a confocal microscope with a environmental chamber to maintain temperature and COâ‚‚.

- For ratiometric sensors like NAPstars, acquire images at two excitation wavelengths (e.g., ~400 nm and for the mCherry reference channel).

- Calculate the ratio image to visualize the spatial distribution of the NADP redox state.

- Stimulus and Control:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Redox Biosensing

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| NAPstar Biosensors [13] | A family of genetically encoded biosensors for the NADPH/NADP+ ratio. | Offers a broad dynamic range and subcellular resolution. Select a variant (e.g., NAPstar1 vs. 6) based on the expected NADPH levels in your system. |

| Grx1-roGFP2 [10] [9] | A biosensor specifically equilibrated with the glutathione (GSH/GSSG) redox couple. | The fusion to glutaredoxin-1 (Grx1) provides specificity and faster response kinetics. Ideal for probing the glutathione system. |

| roGFP2-Orp1 / HyPer Family [10] [11] [9] | Genetically encoded biosensors for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚. | HyPer is pH-sensitive, while newer variants like HyPer7 offer improved stability. roGFP2-Orp1 is a ratiometric, pH-resistant alternative. |

| L-Buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine (BSO) | An inhibitor of glutathione synthesis. | Used to selectively deplete cellular glutathione pools, allowing researchers to dissect its specific role in antioxidative electron flux [13]. |

| Paraquat (PQ) / MitoPQ [12] | Redox-cycling compounds that generate superoxide (O₂•â»). | Useful tools for applying a controlled, specific oxidative challenge within the cytosol or mitochondria. |

| d-Amino Acid Oxidase (DAAO) [12] | A genetically encoded enzyme that produces Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ upon addition of d-alanine. | Allows for controlled, localized, and quantifiable generation of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ inside cells, which is superior to bolus addition of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚. |

| Ethyl 2-cyano-2-(hydroxyimino)acetate | Ethyl Cyanoglyoxylate-2-oxime (Oxyma) | Ethyl cyanoglyoxylate-2-oxime (Oxyma) is a superior, non-explosive peptide coupling additive for low racemization. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| tert-Butyl (3-aminopropyl)carbamate | N-Boc-1,3-propanediamine|CAS 75178-96-0 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core principles behind how genetically encoded redox biosensors function?

Genetically encoded redox biosensors are engineered proteins that convert changes in the cellular redox environment into a measurable optical signal, typically a change in fluorescence. They function based on several core principles [16]:

- Sensing and Reporting Domains: They are typically chimeric proteins combining a sensor domain, which is specific to a redox-active analyte (like Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, NADH, or glutathione), and a reporter domain, which is usually a fluorescent protein (FP).

- Conformational Change: The binding of the target analyte induces a specific conformational change in the sensor domain.

- Signal Modulation: This conformational change alters the environment of the chromophore within the fluorescent protein, modifying its fluorescent properties. This change can be monitored in real-time in live cells.

Q2: What are the key advantages of using genetically encoded biosensors over traditional chemical probes for redox sensing?

Genetically encoded biosensors offer several distinct advantages that make them superior for many live-cell applications [16]:

- Non-invasive and In Situ Monitoring: They allow for monitoring redox states without disrupting the native cellular context, preventing artifacts from sample preparation.

- Subcellular Targeting: Their genetic nature allows for precise targeting to specific organelles (e.g., mitochondria, ER, peroxisomes) using genetic tags, enabling compartment-specific redox measurements.

- High Spatial and Temporal Resolution: Combined with microscopy, they provide resolution from the tissue level down to the nanoscale, allowing for the detection of rapid (sub-second) redox dynamics.

- Multiplexing Potential: Multiple biosensors for different analytes can be expressed and imaged simultaneously in the same cell.

Q3: What specific fluorescence parameters can be recorded from these biosensors, and what equipment is needed?

The fluorescence signal from these biosensors can be recorded using several modalities, each requiring specific instrumentation [17] [16]:

| Recording Modality | Description | Typical Equipment |

|---|---|---|

| Ratiometric Intensity | Measures the ratio of fluorescence at two excitation or emission wavelengths, which cancels out effects of sensor concentration or focus drift. | Standard fluorescence microscopes with appropriate filter sets. |

| Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) | Measures the average time a fluorophore remains in the excited state, which is independent of sensor concentration and excitation light intensity. | Advanced microscopes with time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) capabilities. |

| Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | Measures non-radiative energy transfer between two fluorophores, indicating proximity changes due to analyte binding. | Microscopes capable of detecting two emission channels. |

| Fluorescence Anisotropy/Polarization | Measures the rotation of a fluorophore, which can change upon analyte-induced conformational changes. | Microscopes or plate readers with polarizers. |

Q4: How can non-specific adsorption (NSA) interfere with biosensor measurements, and what are common mitigation strategies?

While NSA is a more significant challenge for surface-based electrochemical biosensors, it can also be a concern in imaging if biosensors adsorb to cellular structures or if the system involves immobilized cells. NSA leads to false-positive signals, reduced sensitivity, and a lower signal-to-noise ratio [2] [1]. Strategies to minimize NSA include:

- Using Ratiometric Biosensors: The ratiometric readout inherently corrects for some artifacts and concentration variations [18].

- Antifouling Coatings: For in vitro assays, surfaces can be modified with hydrophilic, non-charged boundary layers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or specific peptide coatings to prevent protein adsorption [2] [1].

- Optimized Buffer Conditions: The use of surfactants, salts, or carrier proteins in the imaging buffer can help reduce nonspecific interactions [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Low or No Fluorescence Signal from the Biosensor

- Cause 1: Inefficient Transfection or Expression. The biosensor gene may not be efficiently delivered or expressed in the target cells.

- Solution: Optimize transfection protocols (e.g., use different reagents/viral systems), use a stronger promoter, or confirm expression via Western blot.

- Cause 2: Incomplete Chromophore Maturation. Fluorescent proteins require oxygen for chromophore formation.

- Solution: Ensure cells are not in an anoxic environment during expression. Consider using biosensors with improved folding efficiency [16].

- Cause 3: Photobleaching. The fluorophore has been destroyed by excessive light exposure.

- Solution: Reduce light intensity, use a more photostable biosensor variant [16], or employ oxygen-scavenging systems in the medium.

Problem 2: High Background Noise or Non-Specific Signal

- Cause 1: Autofluorescence. Cellular components (e.g., flavins, NADPH) can emit light in the same wavelength range.

- Solution: Use red-shifted biosensors, perform spectral unmixing, or confirm the signal is specific by using a non-responsive biosensor mutant [18].

- Cause 2: Overexpression. Extremely high concentrations of the biosensor can lead to aggregation and non-specific signaling.

- Solution: Titrate the expression level to find the minimum required for a robust signal.

Problem 3: Biosensor Response is Slow or Does Not Match Expected Dynamics

- Cause 1: Limited Binding Kinetics. The biosensor's on/off rates for the analyte may be too slow for the biological process.

- Solution: Use a biosensor with faster kinetics, such as those developed through directed evolution [18].

- Cause 2: Incorrect Subcellular Localization. The biosensor is not reaching its intended compartment.

- Solution: Verify localization using co-staining with organelle-specific dyes and ensure the localization tag is correct and functional [19].

Problem 4: Inconsistent Measurements Between Replicates

- Cause 1: Variation in Biosensor Expression Levels. Cell-to-cell differences in expression can cause intensity variations.

- Solution: Always use ratiometric biosensors where possible to normalize for concentration differences [16] [18].

- Cause 2: Changes in Environmental Conditions. Factors like pH, temperature, and cell density can affect the biosensor's performance.

- Solution: Tightly control incubation and imaging conditions. Use biosensors that are pH-insensitive or measure pH in parallel to correct for its influence [16].

The following table summarizes key parameters for a selection of widely used genetically encoded redox biosensors.

| Biosensor Name | Target Analyte | Sensing Mechanism | Dynamic Range / K_d | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP2 [17] [20] | Glutathione redox potential (E_GSH) | Redox-sensitive disulfide formation alters fluorescence. | Ratiometric (Ex 405/488 nm); calibrated in mV. | Ratiometric, multiple subcellular localization options. |

| Grx1-roGFP2 [17] [19] | Glutathione redox potential (E_GSH) | roGFP2 fused to glutaredoxin for thermodynamic equilibration with glutathione. | Ratiometric (Ex 405/488 nm). | More specific and accurate reporting of the glutathione pool. |

| HyPer7 [20] | Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Circularly permuted GFP (cpGFP) fused to OxyR domain. | ~20-fold increase; K_d ~1.3 μM [16]. | High sensitivity and fast response to H₂O₂. |

| SoNar [16] | NADH/NAD+ ratio | cpFP fused to a bacterial Rex domain. | Ratiometric (Ex 420/485 nm). | Highly responsive to metabolic changes. |

| Peredox-mCherry [20] | NADH/NAD+ ratio | T-sensor based on bacterial Rex domain. | Ratiometric (FRET-based or intensiometric). | Allows absolute quantification of the NADH/NAD+ ratio. |

| cdGreen2 [18] | c-di-GMP (bacterial) | cpEGFP sandwiched between c-di-GMP-binding domains (BldD_CTD). | ~10-fold increase; K_d ~214 nM. | Ratiometric, high temporal resolution, high specificity. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Biosensor Function and Specificity

This protocol outlines key steps to validate a genetically encoded redox biosensor's performance in a live-cell imaging experiment, incorporating checks to ensure data reliability and minimize artifacts.

1. Biosensor Expression and Cell Preparation

- Transfection: Introduce the biosensor plasmid into your target cells using an optimized method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation, viral transduction).

- Selection/Starvation: Allow 24-48 hours for expression and chromophore maturation. For adherent cells, seed them on glass-bottom imaging dishes.

2. System Calibration and Validation

- In-Situ Calibration: At the end of each experiment, perform a calibration to define the minimum (red) and maximum (ox) fluorescence ratio.

- Apply a strong reducing agent (e.g., 10 mM Dithiothreitol, DTT) to achieve the fully reduced state.

- Wash and apply a strong oxidizing agent (e.g., 1-10 mM Hydrogen Peroxide, Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) to achieve the fully oxidized state.

- For controls, treat cells with a non-responsive mutant biosensor under the same conditions [18].

- Specificity Check: Use pharmacological agents to modulate the specific redox pathway of interest and confirm the biosensor responds as expected (e.g., use rotenone to increase mitochondrial NADH and check SoNar response).

3. Live-Cell Imaging and Data Acquisition

- Microscope Setup: Use a confocal or widefield fluorescence microscope equipped with environmental control (37°C, 5% CO₂). Use the appropriate filter sets for ratiometric imaging.

- Image Acquisition: Acquire time-lapse images with minimal laser power and acquisition frequency to avoid phototoxicity and photobleaching. Always use the ratiometric mode.

4. Data Analysis and Artifact Correction

- Ratio Calculation: Calculate the fluorescence ratio (e.g., F405/F488 for roGFP) for each time point and region of interest (single cell or organelle).

- Calibration and Normalization: Normalize the ratio values from the experimental data to the minimum and maximum values obtained during the in-situ calibration, typically expressed as % oxidation or a normalized ratio.

- Background Subtraction: Subtract the background signal from an area without cells for each channel before ratio calculation.

Biosensor Mechanism and Experimental Workflow

Diagram 1: Core mechanism of a genetically encoded redox biosensor.

Diagram 2: Generalized experimental workflow for using genetically encoded redox biosensors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| roGFP2 Plasmids [17] [20] | Monitor glutathione redox potential (E_GSH) in various compartments. | Available from non-profit repositories (e.g., Addgene). Check for validated organelle-targeted versions. |

| HyPer7 Plasmid [20] [16] | Highly sensitive detection of hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) dynamics. | Superior to earlier HyPer variants due to faster response and higher brightness. |

| SoNar Plasmid [16] | Monitor the NADH/NAD+ ratio, reporting on metabolic status. | Highly responsive to metabolic perturbations. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Strong reducing agent for in-situ calibration of thiol-based biosensors. | Use fresh solutions and appropriate concentrations (e.g., 10-50 mM) to define the fully reduced state. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Oxidizing agent for in-situ calibration and experimental modulation. | Use precise concentrations to define the fully oxidized state and to simulate oxidative stress. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [2] [1] | Antifouling coating agent for in vitro setups to reduce non-specific adsorption. | Useful for coating glass surfaces or materials in microfluidic devices to minimize background noise. |

| 2',3'-Didehydro-2',3'-dideoxyuridine | 2',3'-Didehydro-2',3'-dideoxyuridine, CAS:5974-93-6, MF:C9H10N2O4, MW:210.19 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Desformylflustrabromine Hydrochloride | Desformylflustrabromine Hydrochloride, MF:C16H22BrClN2, MW:357.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs on NSA in Redox Biosensing

1. What is Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA) and how does it impact my redox biosensor's performance? NSA refers to the unwanted adhesion of atoms, ions, or molecules (like proteins, lipids, or other cellular components) to your biosensor's surface through physisorption [1]. This occurs via hydrophobic forces, ionic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding [1] [2]. In redox biosensing, this fouling:

- Obscures Specific Signals: Creates a high background signal that is often indistinguishable from the specific binding of your target redox analyte, leading to false positives [1] [2].

- Reduces Sensitivity & Selectivity: The signal from fouling can outweigh the specific biorecognition event, increasing the limit of detection and potentially causing false negatives by blocking analyte access to the bioreceptor [2].

- Damages Sensor Function: In electrochemical sensors, NSA can passivate the electrode, degrade coating layers, and cause significant signal drift over time, complicating data interpretation [2].

2. I'm working with complex samples like serum or cell lysate. Why is NSA a major concern? Complex matrices like blood, serum, and cell lysates contain a high concentration of proteins (e.g., albumin, immunoglobulins) and other biomolecules that readily adsorb to sensing surfaces [2] [21]. One study observed high NSA responses from both cell lysate and serum even on surfaces specifically developed to be "non-fouling" [21]. The chemical complexity of these samples provides numerous opportunities for foulant molecules to interact with and accumulate on your biosensor interface [2].

3. What are the main strategies to minimize NSA in my experiments? Strategies can be broadly categorized as passive (preventing adsorption by coating the surface) and active (dynamically removing adsorption after it occurs) [1].

- Passive Methods: These aim to create a thin, hydrophilic, and non-charged boundary layer to prevent protein adsorption. This includes using chemical coatings (e.g., PEG, hydrogels, zwitterionic materials) or physical adsorption of blocker proteins like BSA or casein [1].

- Active Methods: These are more recent and involve generating surface forces (e.g., electromechanical, acoustic, or hydrodynamic shear forces) to shear away weakly adhered biomolecules after they have adsorbed to the surface [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming NSA

| Problem Scenario | Possible Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background in serum samples. [2] [21] | Sample complexity; fouling from abundant proteins (e.g., albumin). | Apply an antifouling coating (e.g., BSA, PEG) to the sensor surface [22]. Incorporate sample pre-treatment (e.g., dilution, centrifugation) [2]. |

| Signal drift over time in electrochemical detection. [2] | Progressive fouling passivating the electrode and degrading the coating. | Optimize surface chemistry for stability. Use a redox probe in your buffer to monitor surface changes [23]. Implement drift-correction algorithms if applicable [2]. |

| Poor sensitivity despite successful receptor immobilization. | NSA of receptor molecules, leading to denaturation or loss of function [24]. | Use a pre-blocking method. Block defective sites on the surface before immobilizing your bioreceptor to prevent its non-specific adsorption [24]. |

| Low signal from a structure-switching redox aptasensor. | Non-specifically adsorbed molecules restricting the aptamer's required conformational change [2]. | Ensure the antifouling layer is compatible with the aptamer's movement. Consider linker length and surface charge in your design. |

Quantitative Data: Efficacy of Surface Modification Strategies

The following table summarizes the performance of various surface chemistries and modifications in reducing NSA, as reported in the literature.

| Surface Chemistry/Method | Key Parameter | Result/Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA Coating on PMMA microfluidics | Fluorescence reduction of FITC-BSA | >87.6% reduction in protein adsorption [22] | |

| Plasma Cleaning on PMMA microfluidics | Fluorescence reduction of FITC-BSA | 86.1% reduction in protein adsorption [22] | |

| Optimized Alkanethiol SAMs (C10) on low-roughness Au | SPR measurement (ng/mm²) | NSA of fibrinogen: 0.05 ng/mm²; lysozyme: 0.075 ng/mm² [25] | |

| Surface-Initiated Polymerization (SIP) | SPRi response in serum/cell lysate | Showed high sensitivity and minimum NSA versus PEG, cyclodextrin, and dextran [21] | |

| PEG Grafting on PMMA | Stability under varying concentration | Resistance to protein adsorption decreased as concentration increased due to insufficient stability [22] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pre-blocking COOH-SAMs to Inhibit Degradation and Reduce NSA

This protocol uses a gelatin block to protect self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) from ambient oxidation, which creates defects that promote NSA [24].

Reagents:

- 16-Mercaptohexadecanoic acid [HS(CH2)15COOH] (COOH-SAM)

- Anhydrous ethanol

- Gelatin

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Receptor protein (e.g., antibody) and target analyte

Procedure:

- SAM Formation: Immerse clean gold substrates in a 1 mM solution of 16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid in anhydrous ethanol for 18-24 hours to form a dense, well-ordered COOH-SAM [24].

- Pre-blocking: Incubate the COOH-SAM with a 1% (w/v) gelatin solution in PBS for 1 hour.

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the surface with PBS to remove any unbound gelatin.

- Storage: The pre-blocked sensor can be stored in ambient conditions. Studies show this inhibits SAM oxidation for at least one week, unlike unblocked SAMs which degrade significantly in a day [24].

- Functionalization: When ready for use, activate the COOH groups with EDC/NHS chemistry and immobilize your receptor protein (e.g., antibody). The pre-blocking step protects the SAM without preventing subsequent functionalization [24].

Visualization of the Pre-blocking Concept:

Protocol 2: Optimizing Self-Assembled Monolayers on Gold for Microfluidic Biosensors

This protocol outlines key parameters to minimize NSA on alkanethiol SAMs, a common linker surface [25].

Reagents:

- Alkanethiols (e.g., short-chain: C2, long-chain: C10)

- Gold substrates (e.g., on SPR chips)

- Fibrinogen, lysozyme (for NSA challenge tests)

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Use gold surfaces with low root-mean-square (RMS) roughness (~0.8 nm) and strong crystallographic orientation along the (1 1 1) plane. This provides a more uniform surface for SAM formation [25].

- SAM Incubation: Extend the SAM incubation time to at least 18-24 hours to promote the formation of a dense, well-ordered monolayer [25].

- Chain Length Selection: For short-chain alkanethiols (e.g., C2), the gold crystal orientation has a profound effect on reducing NSA. For long-chain alkanethiols (e.g., C10), NSA can be reduced by up to 75%, and they are less sensitive to underlying gold structure [25].

- Validation: Use Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) to quantify the NSA of challenge proteins like fibrinogen and lysozyme onto the optimized SAM. Well-optimized surfaces can achieve NSA levels as low as 0.05 ng/mm² [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in NSA Reduction |

|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A common blocking protein that adsorbs to vacant sites on the sensor surface, preventing subsequent NSA of interferents from the sample [1] [22]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A polymer grafted onto surfaces to create a hydrophilic, steric barrier that repels proteins and other biomolecules through hydration effects [1] [22]. |

| Carboxy-terminated Alkanethiols | Used to form Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) on gold, providing a well-ordered, functional layer for controlled receptor immobilization [24] [25]. |

| Gelatin | Used as a pre-blocking agent to occupy defect sites on SAMs, which inhibits ambient degradation (oxidation) of the SAM and preserves its antifouling properties [24]. |

| Zwitterionic Materials | Create super-hydrophilic surfaces that strongly bind water molecules, forming a physical and energetic barrier to protein adsorption [1]. |

| Surface-Initiated Polymerization (SIP) | A method to create dense, polymer-based antifouling brushes on sensor surfaces, shown to outperform other coatings like PEG in some comparative studies [21]. |

Advanced Materials and Engineering Solutions for Antifouling Redox Biosensors

This technical support center provides practical guidance for researchers developing advanced antifouling coatings to reduce non-specific adsorption (NSA) in redox biosensors. The following troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols are framed within the context of a broader thesis on enhancing biosensor performance in complex biological samples like blood, serum, and milk. The content draws on the latest research to address common experimental challenges and provide reliable methodologies.

The table below summarizes the primary classes of innovative antifouling materials, their core compositions, and critical application parameters to guide your selection process.

Table 1: Overview of Antifouling Material Classes for Biosensors

| Material Class | Core Composition | Key Antifouling Properties | Typical Application Method | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide-Based Coatings | Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), peptide cross-linkers (e.g., GCRDVPMS↓MRGGDRCG) [26] [27] | Disrupt bacterial cell membranes; enzyme-degradable for biosensing [26] [27] | Dopamine-mediated immobilization; covalent grafting [27] | Peptide sequence and stability; immobilization density; activity in liquid media [27] |

| Cross-Linked Protein Films | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), fibrinogen, other globular proteins [2] [28] [29] | Biocompatible; non-immunogenic; forms a hydrophilic, passive barrier [29] | Chemical cross-linking (e.g., with oxidized gellan) [29]; Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembly [28] | Cross-linker toxicity (prefer natural agents); mechanical strength; swelling degree at different pH [29] |

| Hybrid Materials | MIPs@MOFs (e.g., MIL-101(Cr)@MIPs) [30]; Polymer-peptoid brushes [31] | High selectivity from MIPs; large surface area from MOFs; precise molecular control from peptoids [30] [31] | In-situ polymerization on MOF cores; surface-initiated polymerization [30] [31] | Complex synthesis optimization; long-term stability in aqueous environments; cost [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents and materials essential for experimenting with the described antifouling coatings.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antifouling Coating Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| 4-arm PEG Norbornene (PEGNB) | Synthetic polymer backbone for forming hydrogels via "thiol-ene" click chemistry [26] | Used at ~20 kDa molecular weight; cross-linked with specific peptide sequences (e.g., VPM) to create degradable biosensor films [26]. |

| Dopamine Hydrochloride | Versatile coupling agent that polymerizes to form an adhesive polydopamine (PDA) layer on surfaces [27] | Enables subsequent immobilization of AMPs; polymerization is performed in alkaline Tris buffer (pH ~8.5) [27]. |

| Oxidized Gellan (OxG) | Natural, non-toxic cross-linker for protein-based hydrogels [29] | Oxidized by NaIO4 to create dialdehyde groups that form Schiff bases with -NH2 groups on proteins like BSA [29]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymers with tailor-made recognition sites for specific molecules [30] | Used to create core-shell hybrids with Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs like MIL-101(Cr)) for highly selective gas adsorption [30]. |

| Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | Common cross-linker in free radical polymerization, e.g., for creating MIPs [30] | Creates a rigid three-dimensional polymer network around a template molecule [30]. |

| Resveratrol-3-O-sulfate sodium | Resveratrol-3-O-sulfate sodium, CAS:858127-11-4, MF:C14H12NaO6S, MW:331.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Adenosine 5'-succinate | Adenosine 5'-succinate, MF:C14H17N5O7, MW:367.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols for Key Antifouling Strategies

Protocol 1: Fabricating a Peptide Cross-Linked PEG Hydrogel Film for Protease Detection

This protocol is adapted from a study developing a QCM-based biosensor for collagenase [26].

- Substrate Preparation: Clean gold-coated QCM crystals using fresh piranha solution (3:1 v/v concentrated sulfuric acid to 30% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) for 3 minutes. Caution: Piranha solution is highly corrosive and must be handled with extreme care. Rinse thoroughly with Milli-Q water and dry under a nitrogen stream [26].

- Hydrogel Precursor Solution:

- Prepare stock solutions of 4-arm PEG Norbornene (PEGNB, 20 kDa) and the peptide cross-linker (e.g., VPM) in PBS at pH 6.

- For a 50% cross-linked hydrogel, mix 104.2 µL of PEGNB stock (20 mM) with 17.8 µL of VPM peptide stock (10 mM).

- Add PBS pH 6 to bring the total volume to 200 µL.

- Add 5 mol% (relative to thiol groups) of the photo-initiator Irgacure 2959 [26].

- Film Deposition and UV-Curing:

- Sandwich the hydrogel mixture between the clean QCM crystal and a silanized (non-adhesive) glass slide.

- Expose the assembly to UV light (17 mW/cm², 350–500 nm) for 300 seconds to cure.

- Separate the coated QCM crystal and store in PBS buffer until use [26].

Protocol 2: Dopamine-Mediated Immobilization of Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs)

This protocol describes a robust method for functionalizing metallic surfaces (e.g., stainless steel) with AMPs [27].

- Surface Priming with Polydopamine (PDA):

- Prepare a dopamine solution (2 mg/mL) in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 8.5.

- Immerse the thoroughly cleaned substrate in this solution for 8 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. This results in a uniform PDA coating of ~30 nm [27].

- Rinse the PDA-coated substrate with deionized water to remove any loosely bound dopamine.

- AMP Immobilization:

- Prepare a solution of the selected antimicrobial peptide in an appropriate buffer (e.g., PBS).

- Incubate the PDA-coated substrate with the AMP solution for 24 hours at 4°C. The quinone groups in the PDA layer react covalently with amine groups on the peptides [27].

- Rinse the functionalized surface with buffer to remove any unbound peptides.

Protocol 3: Constructing Protein-Based Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Films

The LbL method is a versatile technique for building thin, multifunctional coatings [28].

- Surface Charging: Start with a substrate (e.g., gold, glass) that has been cleaned and possesses a known surface charge (often negative). A silanization step can be used to ensure a strong positive charge [28].

- Alternating Deposition:

- Immerse the charged substrate in a solution of the polyanion (e.g., a protein like BSA or a polysaccharide) for 10-20 minutes to adsorb a monolayer.

- Rinse with water or buffer to remove weakly adsorbed molecules.

- Immerse the substrate in a solution of the polycation (e.g., a synthetic polymer like PAH or a positive protein) for 10-20 minutes.

- Rinse again.

- This two-step process forms one "bilayer". Repeat the cycle to achieve the desired number of bilayers and film thickness [28].

- Film Characterization: Use techniques like quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation (QCM-D) or ellipsometry to monitor the growth of the film in real-time [28].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Our biosensor's electrochemical signal drifts significantly when testing in serum. What is the likely cause and how can we address it?

Answer: Signal drift in complex matrices like serum is highly indicative of progressive nonspecific adsorption (NSA), or fouling, on the sensing interface [2]. As proteins and other biomolecules accumulate over time, they can passivate the electrode, degrade the coating, and restrict the conformational freedom of structure-switching bioreceptors like aptamers [2].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify the Antifouling Coating: Ensure your coating is uniform and intact. Techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) can be used to characterize NSA.

- Increase Coating Density/Thickness: If using a polymer brush or LbL film, try increasing the grafting density or the number of bilayers to create a more effective barrier [28] [31].

- Incorporate Zwitterionic Materials: Consider incorporating zwitterionic polymers or peptides, which are highly hydrophilic and strongly bind water molecules to create a physical and energetic barrier to fouling [2] [27].

- Optimize Sample Dilution/Buffer: As a preliminary measure, diluting the serum sample or adding mild surfactants to the running buffer can help reduce fouling intensity [2].

FAQ 2: The peptide cross-linked hydrogel we synthesized for a protease sensor shows low degradation response and poor sensitivity. How can we improve its performance?

Answer: Low sensitivity can stem from issues with hydrogel density, peptide accessibility, or enzyme activity.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize Cross-linking Density: A highly dense hydrogel network may hinder enzyme diffusion. Systematically vary the molar ratio of peptide cross-linker to PEGNB (e.g., from 50% to 100%) to find the optimal balance between film stability and enzyme accessibility [26].

- Verify Peptide Susceptibility: Confirm that the specific peptide sequence used is efficiently cleaved by your target protease. Use MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to analyze degradation products after enzyme incubation [26].

- Check Enzyme Activity: Ensure the enzyme (e.g., collagenase) is active under your experimental conditions (pH, temperature, presence of necessary co-factors like Zn²⺠or Ca²âº). Use a commercial activity assay kit as a positive control [26].

FAQ 3: The stability of our hybrid MOF-based antifouling coating is poor in aqueous solutions. What strategies can enhance its durability?

Answer: The stability of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) in water can be a limitation. Strategies focus on protective layering and robust composite formation.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Create a Core-Shell Structure: Encapsulate the MOF core (e.g., MIL-101(Cr)) within a protective polymer shell, such as a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP). This shell shields the MOF from water while adding selective antifouling properties [30].

- Post-Synthetic Modification: Chemically modify the external surface of the MOF with hydrophobic groups to improve its water resistance.

- Explore Alternative MOFs: Consider using MOFs known for their hydrolytic stability, such as those based on zirconium (Zrâ´âº) or iron (Fe³âº), instead of chromium-based structures.

Visualizing Key Concepts and Workflows

Diagram: Impact of Fouling on a Redox Biosensor

Diagram: Workflow for Developing an Antifouling Coating

Harnessing Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Conductive Polymers for Enhanced Electron Transfer

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource is designed for researchers developing redox biosensors, with a specific focus on mitigating non-specific adsorption. The integration of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and conductive polymers presents a powerful strategy to enhance electron transfer, and this guide addresses common experimental challenges encountered in this process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I improve the low electrical conductivity of pristine MOFs in my biosensor electrode?

Answer: The low intrinsic conductivity of many MOFs is a common limitation. The most effective strategy is to form composites with conductive materials.

- Recommended Solution: Integrate MOFs with conductive polymers or carbon-based materials. The synergistic effect between the materials enhances electron transfer pathways. For instance, MOFs can act as scaffolds for conductive polymers like polyaniline (PANI), creating interconnected networks that boost overall conductivity without sacrificing the high surface area of the MOF [32] [33]. One study created a sandwiched sensor design using a composite of C-MOF and PANI, which demonstrated high sensitivity and fast response times [34].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If conductivity remains low, ensure the conductive polymer has fully penetrated the MOF's pores. Optimizing the synthesis method, such as using in-situ polymerization of the monomer within the MOF, can achieve a more uniform composite.

FAQ 2: What are the best methods to functionalize MOF-conductive polymer composites to reduce non-specific adsorption?

Answer: Non-specific adsorption can foul the electrode surface and reduce sensor accuracy. Functionalization creates a more selective biosensing interface.

- Recommended Solution: Employ post-synthetic modification to graft hydrophilic or antifouling molecules onto the MOF's surface. The tunable porosity and functional surfaces of MOFs allow for the incorporation of biomolecules like enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers that provide specific recognition for your target analyte, thereby reducing interference from non-target species [35] [36]. The functional groups on the MOF's organic linkers can be used to covalently bind these biorecognition elements.

- Troubleshooting Tip: If non-specific adsorption persists, characterize the surface charge and hydrophilicity of your composite. Introducing negatively charged or hydrophilic polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol) as a co-modifier can further create a repellent layer against common interferents like proteins.

FAQ 3: How can I address the stability issues of MOF-based composites in aqueous or complex biological solutions?

Answer: Stability is critical for biosensors operating in physiological fluids. Some MOFs are susceptible to hydrolysis, especially in aqueous environments [36].

- Recommended Solution: Select MOFs known for their robust stability in water. Frameworks from the UiO or ZIF series, particularly those incorporating zirconia or cobalt, often demonstrate higher resistance to hydrolysis [36]. Alternatively, forming a composite with a conductive polymer can sometimes shield the MOF structure and enhance its overall mechanical and chemical stability.

- Troubleshooting Tip: Before testing in complex samples like serum or sweat, validate the composite's stability in a buffer solution over the intended operational timeframe. Monitor for changes in electrochemical signal or material morphology to confirm stability.

FAQ 4: My MOF-based biosensor has inconsistent performance. How can I improve its reproducibility?

Answer: Reproducibility is key for reliable biosensing. Inconsistencies often stem from variations in material synthesis or electrode fabrication.

- Recommended Solution: Strictly control all synthesis parameters, including temperature, reaction time, and precursor concentrations, to ensure batch-to-batch consistency of your MOF [34]. When preparing the composite, use well-established methods like in-situ growth or electrochemical deposition to ensure a uniform integration of the conductive polymer.

- Troubleshooting Tip: Implement rigorous material characterization (e.g., SEM, XRD, BET surface area analysis) for each new batch to verify consistent morphology, crystallinity, and porosity.

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Performance of MOF-Based Composites in Redox Biosensing

| Composite Material | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Key Advantage for Reducing Non-Specific Adsorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-MOF/SPCE [37] | Ascorbic Acid | 1 μM | 2 - 200 μM | Unique structure allows specific binding to active sites. |

| Pd-doped Ni-MOF [37] | Dopamine | 0.01 μM | 0.001 - 100 μM | Enhanced catalytic activity and anti-interfering properties. |

| Ag-doped Ni-MOF [37] | Glucose | 5 μM | Not Specified | High sensitivity and selectivity in complex samples. |

| MOF-on-MOF Heterostructure [36] | Various Biomolecules | Low nM range | Not Specified | Precise pore engineering for size-selective recognition. |

| MOF/Hydrogel Composite [33] | Biomarkers in Sweat | Not Specified | Not Specified | Hydrogel matrix acts as a selective barrier, filtering interferents. |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of a ZIF-8/Conductive Polymer Composite

This protocol outlines a common method for creating a MOF/conductive polymer composite suitable for electrode modification [32] [35].

Objective: To synthesize a uniform composite of ZIF-8 and a conductive polymer (e.g., polyaniline, PANI) for enhanced electron transfer and selective biosensing.

Materials:

- Metal Salt: Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O)

- Organic Linker: 2-Methylimidazole

- Conductive Polymer Monomer: Aniline

- Solvent: Methanol

- Oxidizing Agent: Ammonium persulfate

- Dopant Acid: Hydrochloric acid (HCl)

Procedure:

- Synthesis of ZIF-8 Nanoparticles:

- Dissolve zinc nitrate (1.0 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol (Solution A).

- Dissolve 2-methylimidazole (4.0 mmol) in 20 mL of methanol (Solution B).

- Rapidly pour Solution B into Solution A under constant stirring.

- Continue stirring at room temperature for 2 hours.

- Centrifuge the resulting white precipitate and wash with methanol three times. Dry the product at 60°C overnight.

- In-Situ Polymerization of PANI within ZIF-8:

- Disperse 50 mg of the synthesized ZIF-8 powder in 20 mL of 1M HCl.

- Add 50 μL of aniline monomer to the dispersion and sonicate for 30 minutes to allow the monomer to diffuse into the MOF pores.

- Dissolve 100 mg of ammonium persulfate in 5 mL of 1M HCl and cool it in an ice bath.

- Slowly add the oxidant solution dropwise to the ZIF-8/aniline mixture under vigorous stirring. Maintain the reaction in an ice bath for 4-6 hours.

- The color change to dark green indicates the formation of PANI.

- Centrifuge the ZIF-8/PANI composite, wash with water and ethanol, and dry under vacuum.

Integration into Electrode:

- Prepare an ink by dispersing 5 mg of the ZIF-8/PANI composite in 1 mL of a water/ethanol mixture (1:1 v/v) with a few μL of Nafion binder.

- Drop-cast a calculated volume of the ink onto a clean glassy carbon electrode and allow it to dry at room temperature.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for MOF-Based Redox Biosensors

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIF-8) | Provides high surface area and tunable porosity for immobilizing biorecognition elements; enhances selectivity [32] [35]. | Used as a porous scaffold to host enzymes for glucose sensing, improving stability and loading capacity [32]. |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., PANI, PPy) | Creates electron transfer pathways, boosting the electrical conductivity of the composite; can be functionalized [34] [32]. | Polyaniline (PANI) is composited with MOFs to form a 3D conductive network in wearable pressure sensors [34]. |

| Nickel-Based MOFs (Ni-MOFs) | Offers intrinsic redox activity due to Ni²âº/Ni³⺠couple, useful for direct electrocatalysis of small molecules [37]. | Employed for the non-enzymatic detection of ascorbic acid and glucose, leveraging its electrocatalytic properties [37]. |

| Noble Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag NPs) | Enhances electrocatalytic activity, improves signal amplification, and can be used for biomolecule immobilization [32] [35]. | Silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) doped onto Ni-MOFs significantly improve sensitivity for dopamine detection [37]. |

| Hydrogels | Provides a biocompatible, flexible matrix for wearable sensors; can act as a selective barrier to reduce fouling [33]. | Integrated with MOFs in sweat sensors to enhance skin compatibility and filter out large interferents [33]. |

| N6-Benzyl-5'-ethylcarboxamido Adenosine | N6-Benzyl-5'-ethylcarboxamido Adenosine, CAS:152918-32-6, MF:C19H22N6O4, MW:398.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Acetyl-S-methyl-L-cysteine-d3 | N-Acetyl-S-methyl-L-cysteine-d3, MF:C6H11NO3S, MW:180.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the strategic approach and electron transfer pathways involved in developing these advanced biosensors.

Diagram 1: Biosensor Development and Electron Transfer Workflow. This chart outlines the key stages in constructing a MOF-based biosensor and highlights the crucial electron transfer pathway that enables sensitive detection.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental principle behind using Redox Imbalance as a Driving Force (RIFD) in metabolic engineering?

The RIFD strategy is based on intentionally creating an imbalance in the cell's redox cofactors, specifically the NADPH/NADP+ ratio, to exert a selective pressure that drives metabolic flux toward your desired product [38]. By engineering a cellular state of "excessive NADPH," you create a growth inhibition that forces the cell to evolve solutions to alleviate this stress. When combined with a product biosynthesis pathway that consumes NADPH, the cell's adaptive evolution is channeled toward high-yield production, as this simultaneously restores redox balance and improves growth [38].

FAQ 2: Why is non-specific adsorption (NSA) a critical problem in redox biosensing, and how does it affect my readings?

NSA occurs when biomolecules physisorb onto your sensor's surface, leading to high background signals that are often indistinguishable from specific binding events [39]. This biofouling decreases sensitivity and specificity, increases the false-positive rate, and reduces the reproducibility of your biosensor [39]. For redox biosensors that rely on accurate, real-time monitoring of cofactor ratios like NADPH/NADP+, these false signals can severely distort the measured intracellular dynamics, leading to incorrect conclusions about the metabolic state [40] [13].

FAQ 3: What are the primary methods to reduce Non-Specific Adsorption in biosensor surfaces?

Methods for NSA reduction are broadly categorized as passive (blocking) or active (removal) [39]. The table below summarizes the main approaches:

Table: Methods for Reducing Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA) on Biosensors

| Method Category | Sub-Type | Key Principle | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passive (Blocking) | Physical | Coating the surface with inert proteins to block vacant sites [39]. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein |

| Chemical | Creating a hydrophilic, non-charged boundary layer to prevent physisorption [39]. | Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) | |

| Active (Removal) | Transducer-based | Generating surface forces (e.g., shear) to physically desorb weakly adhered molecules [39]. | Electromechanical (e.g., piezo) devices, acoustic (e.g., ultrasound) devices |

| Fluid-based | Using controlled fluid flow over the surface to shear away non-specifically bound molecules [39]. | Microfluidic flow cells |

FAQ 4: My engineered strain with a targeted redox imbalance shows severe growth inhibition. Is this expected, and how can I resolve it?

Yes, growth inhibition is an expected and often a deliberate outcome in the initial stages of applying the RIFD strategy [38]. This inhibition creates the selective pressure necessary to drive evolution. To resolve it, you should couple the redox imbalance with an adaptive evolution strategy. This involves using serial passaging or high-throughput evolution techniques like Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) to allow spontaneous beneficial mutations to arise [38]. Coupling this evolution with a NADPH or product-specific biosensor and Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) enables the efficient selection of high-performing mutants that have restored redox homeostasis by overproducing your target compound [38].

FAQ 5: How can I verify that my biosensor is accurately reporting NADPH/NADP+ ratios and not being influenced by other cellular redox couples?

This is a critical validation step. Earlier redox sensors based on roGFP2 were prone to interference because they could equilibrate with the glutathione redox couple [13]. You should:

- Use a Validated Sensor: Employ next-generation, specific biosensors like the recently developed NAPstar family, which are designed for high specificity to the NADP redox couple across a wide dynamic range [13].

- Perform Control Experiments: Characterize your sensor's response in vitro and in your host system under controlled perturbations. The NAPstar sensors, for instance, have been shown to have a substantially weaker affinity for NADH (one to two orders of magnitude lower) than for NADPH, ensuring specificity [13].

- Check for pH Sensitivity: Ensure your chosen sensor has limited pH sensitivity to avoid conflating pH changes with redox changes, a feature offered by sensors like Peredox and the derived NAPstars [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Specificity in Redox Biosensor Readings

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Ineffective Passivation of Sensor Surface. The biosensor's surface is prone to biofouling from proteins in the complex cellular lysate or media.

- Cause 2: Sensor Cross-Talk with Similar Redox Cofactors. The biosensor may be responding to NADH/NAD+ in addition to NADPH/NADP+.

- Solution: Verify sensor specificity by consulting its characterization data. For monitoring NADPH/NADP+, consider using the newly developed NAPstar biosensors, which have a Kr(NADPH/NADP+) ranging from ~0.9 µM to 11.6 µM and significantly lower affinity for NADH [13].

- Cause 3: Interfering Substances in Complex Biological Matrices. Components in serum, blood, or cell lysates can generate non-faradaic signals or foul the electrode.

- Solution: Integrate an active NSA removal method. If using a microfluidic setup, implement periodic or continuous hydrodynamic flow to generate shear forces that wash away loosely adsorbed molecules [39]. For surface-based sensors, transducer-based methods like acoustic shaking can be effective.

Problem: Failure to Achieve a Sufficient Redox Imbalance to Drive Production

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate "Open Source" Strategy. The pathways generating NADPH are not sufficiently amplified.

- Solution: Implement a multi-pronged "open source" approach [38]:

- Express a soluble transhydrogenase (e.g., pntAB) to convert NADH to NADPH [41] [38].

- Overexpress enzymes in the native NADPH synthesis pathway (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, zwf).

- Introduce heterologous NADPH-dependent enzymes or re-engineer native NADH-dependent enzymes to use NADPH [38].

- Solution: Implement a multi-pronged "open source" approach [38]:

- Cause 2: Inefficient "Reduce Expenditure" Strategy. Native cellular processes are wasting the NADPH you are generating.

- Solution: Use CRISPRi or knockout strategies to downregulate non-essential genes that consume large amounts of NADPH, thereby conserving the pool for your biosynthetic pathway of interest [38].

- Cause 3: Insufficient Evolutionary Pressure. The strain is not being effectively forced to couple redox balance restoration with product synthesis.

- Solution: Employ a rigorous adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) protocol. Use MAGE for targeted, multiplexed genome engineering to introduce diversity, and then leverage a biosensor-based high-throughput screening system to isolate top producers [38].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a Basic RIFD Strategy inE. colifor L-Threonine Production

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a redox imbalance force-driven strain, based on the work that achieved 117.65 g/L of L-threonine [38].

1. Principle: Engineer an "excessive NADPH" state using "open source and reduce expenditure," then use evolution to select for mutants that alleviate this stress by overproducing an NADPH-consuming product.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- E. coli chassis strain

- Plasmid vectors for gene expression (e.g., pET, pRSF)

- CRISPR-Cas9 system for gene knockdown

- MAGE oligonucleotides for genome engineering

- Materials for fermentation (bioreactor, defined media)

- FACS sorter

3. Procedure: Step 1: Create Redox Imbalance.

- "Open Source": Introduce and overexpress genes that increase the NADPH pool. This includes:

- Cofactor-converting enzymes (e.g., pntAB for transhydrogenase).

- Heterologous NADPH-generating enzymes (e.g., NADP+-dependent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase).

- Enzymes in the NADPH synthesis pathway (e.g., zwf).

- "Reduce Expenditure": Identify and knock down non-essential genes that are major NADPH consumers (e.g., gnd).

Step 2: Evolve the Redox-Imbalanced Strain.

- Subject the growth-inhibited strain to serial passaging in a bioreactor or shake flasks.

- Alternatively, use Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering (MAGE) to introduce random mutations targeted to genomic regions associated with central metabolism and the L-threonine pathway [38].

Step 3: High-Throughput Screening of Evolved Mutants.

- Develop a dual-sensing biosensor that responds to both intracellular NADPH levels and L-threonine concentration [38].

- Use Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to screen large mutant libraries and isolate clones that show both a restored NADPH level (indicating resolved stress) and high L-threonine production [38].

Step 4: Fermentation Validation.

- Validate the performance of selected high-yield clones in controlled bioreactors to assess final titer, yield, and productivity.

Protocol 2: Assessing NADP Redox State with Genetically Encoded Biosensors

This protocol describes how to use the NAPstar family of biosensors to monitor the real-time dynamics of the NADPH/NADP+ ratio in vivo [13].

1. Principle: The NAPstar biosensor is a single polypeptide containing a circularly permuted T-Sapphire fluorescent protein flanked by two Rex domains. Binding of NADPH or NADP+ induces a conformational change that alters the fluorescence, which can be measured ratiometrically against a fused mCherry reference.

2. Reagents and Equipment:

- NAPstar plasmid (e.g., NAPstar1, 2, or 3 from AddGene)

- Equipment for transfection/transformation

- Confocal microscope or fluorescence plate reader with capable filters (excitation ~400 nm, emission ~515 nm for T-Sapphire; excitation ~587 nm, emission ~610 nm for mCherry)

- FLIM-capable microscope (optional)

3. Procedure: Step 1: Sensor Expression.

- Clone the NAPstar gene sequence into an appropriate expression vector for your host (yeast, mammalian cells, plants).

- Transfect/transform your target cells and confirm expression.

Step 2: Ratiometric Measurement.

- For a plate reader, excite the sensor at 400 nm and 487 nm, and measure the emission at 515 nm for the T-Sapphire channel. Also, excite at 587 nm and measure emission at 610 nm for the mCherry channel.

- Calculate the ratio of T-Sapphire fluorescence (with 400 nm excitation) to mCherry fluorescence. This ratio is inversely correlated with the NADPH/NADP+ ratio [13].

- Note: The in vitro characterized Kr(NADPH/NADP+) values for different NAPstars range from ~0.001 to 5, allowing you to choose a sensor variant matched to your expected redox state [13].

Step 3: Data Calibration and Validation.

- Perform in vivo calibration by treating cells with diamide (oxidant) and DTT (reductant) to define the minimum and maximum ratio values.

- For subcellular resolution, use confocal microscopy. The NAPstar sensor can also be used with Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) for a quantitative measurement that is independent of sensor concentration [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for Redox Cofactor Engineering and Biosensing

| Item Name | Function/Description | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| NAPstar Biosensors [13] | A family of genetically encoded, fluorescent protein-based biosensors for specific, ratiometric measurement of the NADPH/NADP+ redox state. | Real-time, subcellular monitoring of NADP redox dynamics in vivo. |

| SoNar / iNAP Biosensors | Earlier generations of genetically encoded biosensors for NADH/NAD+ and NADPH, respectively. Useful but may have limitations in specificity or pH sensitivity [40]. | Monitoring intracellular pyridine nucleotide levels. |

| MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) [38] | A technology that uses synthetic oligonucleotides to introduce targeted mutations across the genome at high efficiency. | Rapid, multiplexed strain evolution to overcome redox imbalance and improve production. |

| FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting) [38] | A specialized type of flow cytometry that sorts a heterogeneous mixture of cells based on their fluorescent signals. | High-throughput screening of mutant libraries using biosensor signals (e.g., NADPH or product-specific). |

| Peredox-mCherry | A genetically encoded biosensor for the NADH/NAD+ redox state, which served as the chassis for developing NAPstars [13]. | Monitoring the NADH/NAD+ redox couple. |

| Transhydrogenase (pntAB) [41] [38] | An enzyme that catalyzes the reversible transfer of reducing equivalents between NADH and NADP+. | "Open Source" strategy for increasing the NADPH pool from NADH. |

| N-t-Boc-valacyclovir-d4 | N-t-Boc-valacyclovir-d4, CAS:1346617-11-5, MF:C18H28N6O6, MW:428.482 | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common causes of high background signal (noise) in electrochemical biosensors? The most prevalent cause is Non-Specific Adsorption (NSA), where non-target molecules (e.g., other proteins, biomolecules) physisorb to the sensor surface. This biofouling leads to false-positive signals, reduces sensitivity, and compromises the limit of detection. NSA occurs due to hydrophobic forces, ionic interactions, and van der Waals forces between the sensor surface and molecules in complex samples like serum or milk [39].

2. What strategies can I use to reduce Non-Specific Adsorption? Strategies are categorized as passive (blocking) or active (removal). Passive methods involve coating the surface with physical blockers (e.g., bovine serum albumin) or chemical layers (e.g., PEG-based hydrogels, self-assembled monolayers) to create a hydrophilic, non-charged barrier. Active methods use external forces, such as electromechanical or acoustic transducers within microfluidic systems, to generate shear forces that dynamically remove adsorbed molecules post-functionalization [39].

3. My biosensor's sensitivity has dropped after testing multiple serum samples. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of sensor surface fouling. The complex matrix of serum leads to a buildup of non-specifically adsorbed proteins, effectively "clogging" the sensor. To remediate, implement a rigorous regeneration protocol between analyses using a combination of chemical washes (e.g., glycine-HCl buffer) and consider redesigning the sensor with more robust antifouling coatings like UV-crosslinked PEGDA hydrogels, which have shown improved stability in biosensors designed for biofluids [42] [39].

4. How can I detect multiple analytes, like a pathogen and an antibiotic, in the same milk sample? This requires a multi-plexed sensing platform. You can functionalize different electrode arrays within a single device with specific biorecognition elements (e.g., an aptamer for Salmonella and an antibody for Penicillin G). Using a handheld potentiostat with multi-channel capability, you can measure the distinct electrochemical signals (e.g., amperometric for one, impedimetric for another) simultaneously. Nanomaterials like reduced graphene oxide (rGO) or gold nanoparticles can be used on different electrodes to enhance signal specificity and prevent cross-talk [43].