Optimizing Redox Biosensor Arrays: A Comprehensive Guide to Calibration Protocols for Reliable Biomedical Sensing

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the calibration of redox biosensor arrays, a critical technology for sensitive detection in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics.

Optimizing Redox Biosensor Arrays: A Comprehensive Guide to Calibration Protocols for Reliable Biomedical Sensing

Abstract

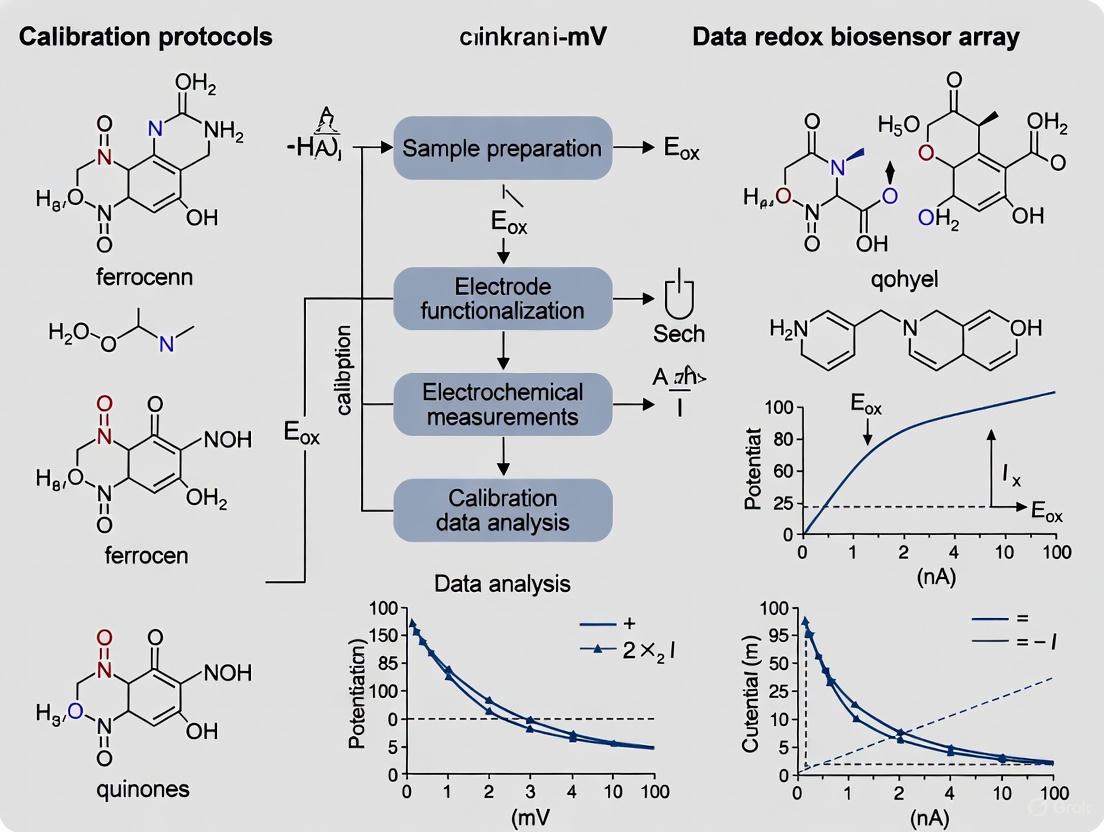

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the calibration of redox biosensor arrays, a critical technology for sensitive detection in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. It covers the fundamental principles of redox sensing and signal transduction, details step-by-step methodologies for establishing robust calibration protocols, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and outlines rigorous validation and performance comparison against established clinical standards. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource is designed to enhance the accuracy, reproducibility, and translational potential of biosensor-based assays.

Understanding Redox Biosensor Fundamentals: Principles, Components, and Signal Transduction

Core Principles of Redox Probe Electrochemistry in Biosensing

Redox probes are small, electroactive molecules that undergo oxidation and reduction reactions at defined potentials, providing a direct, measurable signal that reflects the properties of the electrode–solution interface. They serve as fundamental tools in electrochemical sensor development, acting as indicators of electron transfer dynamics and enabling researchers to gain insight into the structure, chemistry, and function of sensor interfaces. By monitoring their behavior using techniques like cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), or square wave voltammetry (SWV), researchers can qualitatively and quantitatively assess redox activity, peak potential, reversibility, and diffusion behavior—all crucial parameters for understanding sensor performance [1].

In biosensor development, redox probes play multiple essential roles. They provide electrochemical quality control for new electrodes, help track how surface modifications affect electron transfer, serve as diagnostic tools for surface characterization, and can act as mediators that shuttle electrons between biological recognition elements and electrode surfaces. Their sensitivity to electron transfer pathways makes them effective "electrochemical reporters" for surface accessibility and functionality [1].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Electron Transfer Dynamics

Redox probes function by exchanging electrons with electrode surfaces at characteristic potentials. This electron transfer can occur through different mechanisms depending on the probe's relationship to the electrode interface:

- Outer-sphere redox probes (e.g.,

[Ru(NH₃)₆]³âº/²âº) do not specifically interact with the electrode surface and are valuable for assessing intrinsic electron transfer rates. - Surface-sensitive probes (e.g.,

[Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») interact more strongly with electrode surfaces, particularly carbon-based materials, making their behavior dependent on surface chemistry and functional groups [2].

The Nernst equation fundamentally describes the potential-dependent behavior of redox probes:

Where E is the measured potential, E° is the standard reduction potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant, and [Ox]/[Red] is the ratio of oxidized to reduced species concentrations [3].

Redox Cycling and Signal Amplification

Many advanced biosensing platforms utilize redox cycling mechanisms to amplify signals and improve detection limits. This involves continuous oxidation and reduction of probe molecules between adjacent electrodes or using enzymatic recycling. For example, in potentiometric sensor arrays, electron mediators like ferrocene can shuttle electrons between enzymes and electrodes, enabling detection of biologically relevant molecules like glutamate at micromolar concentrations [3].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Redox Probes and Their Applications in Biosensor Characterization

| Redox Probe | Electrode Compatibility | Key Characteristics | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

[Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» |

Carbon, Gold, Platinum | Inexpensive, surface-sensitive, quasi-reversible kinetics | General sensor characterization, working area estimation [2] |

[Ru(NH₃)₆]³âº/²⺠|

Carbon, Gold, Platinum | Near-ideal outer-sphere behavior, higher cost | Assessing electron transfer rates, fundamental studies [2] |

| Ferrocene Derivatives | Various | Mediating properties, tunable chemistry | Enzyme-based biosensors, glucose detection [1] [3] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Platinum, Modified electrodes | Biological relevance, reactive oxygen species | Immune response monitoring, enzymatic reaction detection [4] |

| Phenazines | Graphene-modified electrodes | Microbial signaling molecules, reversible cycling | Bacterial communication studies, infection detection [4] |

Table 2: Supporting Reagents and Materials for Redox Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | KCl, NaCl, buffer solutions | Provides ionic strength, controls mass transport [2] |

| Enzyme Immobilization Matrix | Poly-ion-complex (PLL/PSS) | Entraps enzymes while allowing substrate diffusion [3] |

| Electrode Cleaning Solutions | 1M HCl, commercial dishwashing liquid, chlorine bleach | Removes contaminants from electrode surfaces [5] |

| Calibration Standards | Commercial ORP standards (e.g., 100 mV, 300 mV) | Verifies and calibrates sensor response [6] |

| Storage Solutions | pH-4/KCl solution | Preserves electrode function during storage [6] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Sensor Preparation and Calibration

Q: Why does my redox sensor show drifting readings or unstable potentials? A: Redox reference electrodes naturally drift over time, with intensification as they age. This can be caused by a dirty/contaminated electrode surface, reference system malfunction, or moisture in the cable. For dirty electrodes, clean with distilled water and gently wipe the electrode metal with fine polishing powder. If drift persists, check for damaged contacts, short circuits in the connector, or contamination of the reference system by sulfides, cyanides, or heavy metals [7].

Q: How often should I calibrate my redox sensors, and what standards should I use? A: Calibration frequency depends on usage intensity and application criticality. For research applications, verify calibration daily when the instrument is in use. New sensors may hold calibration for several days, while heavily used sensors may require more frequent calibration. Use two commercial ORP standards (typically 100 mV and 300 mV) for a proper two-point calibration. Single-point calibration can address offset errors when they occur between full calibrations [5] [6].

Q: What are the expected millivolt values for a properly functioning redox sensor? A: While absolute values depend on your specific system, in calibration conditions:

- The mV span between different pH buffers should be approximately 165-180 mV, with 177 mV being ideal

- The slope should be 55-60 mV per pH unit, with 59 mV per pH unit as the ideal

- If the mV span drops below 160, clean the sensor and recalibrate [5]

FAQ: Data Interpretation and Quality Issues

Q: Why do my redox peaks appear in the "wrong" place or show distorted shapes? A: Variations from expected redox behavior are windows into surface chemistry and interface properties rather than necessarily indicating instrument failure. Common causes include:

- Electrode surface contamination (clean with appropriate solutions)

- Inadequate surface preparation or activation

- Incorrect redox probe selection for your electrode material

- Changes in electrode surface properties due to modification steps

- Electrical contact resistance issues, particularly with 3D-printed electrodes [1] [2]

Q: My sensor shows slow response times—what could be causing this? A: Slow response typically indicates:

- Fouling or contamination on the electrode surface

- Biological film formation in biological samples

- Aging sensor requiring reconditioning

- Blocked reference electrode junction For slow response, clean and recondition the sensor using established protocols [5].

Q: Can I use [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» to accurately determine my electrode's active surface area?

A: While commonly used for this purpose, [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» has limitations for accurate surface area determination, especially with rough or non-planar electrodes. Its surface-sensitive nature results in quasi-reversible kinetics, particularly on carbon electrodes, which can lead to inaccurate area estimations. [Ru(NH₃)₆]³âº/²⺠provides more reliable results for fundamental electron transfer assessment, though neither method detects surface roughness much smaller than the diffusion layer thickness (~100 µm) [2].

FAQ: Sensor Maintenance and Lifetime

Q: What is the typical lifespan of redox sensors, and how can I extend it? A: The typical working life for redox sensors is approximately 12-24 months, depending on usage, storage, and maintenance. Proper storage and maintenance generally extend the sensor's working life. With proper storage—at room temperature, in the recommended electrolyte, and with a protective cap on—sensors can function properly for up to a year even with regular use [5] [7].

Q: How should I properly clean and recondition my redox sensors? A: Follow these sequential cleaning steps:

- Initial cleaning: Moisten a soft clean cloth, lens cleaning tissue, or cotton swab to remove foreign material from the electrode surfaces. Carefully remove material blocking the reference electrode junction.

- Mild cleaning: Soak the sensor for 10-15 minutes in clean water with a few drops of commercial dishwashing liquid. Gently clean with a cotton swab soaked in the solution.

- Acid treatment: Soak for 30-60 minutes in 1M hydrochloric acid (HCl) for stubborn contamination.

- Bleach treatment: For biological contamination, soak for ~1 hour in a 1:1 dilution of commercial chlorine bleach.

CRITICAL SAFETY NOTE: Never mix acid and bleach steps sequentially without copious rinsing in between, as this can produce toxic gas [5].

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

Standard Calibration Protocol for Redox Sensors

Standard Two-Point Redox Sensor Calibration Workflow

Step-by-Step Calibration Procedure:

Preparation: Rinse the sensor tip with distilled water and prepare two commercial ORP standards (typically 100 mV and 300 mV).

First Calibration Point:

- Immerse the sensor in the first standard solution

- Wait for the voltage reading to stabilize (may take several minutes)

- Enter the known mV value of the first standard (e.g., 100 mV) into your data collection software

Second Calibration Point:

- Remove the sensor from the first standard and rinse thoroughly with distilled water

- Place the sensor into the second standard solution

- Wait for voltage stabilization

- Enter the known mV value of the second standard (e.g., 300 mV)

Completion:

- Rinse the sensor with distilled water

- The sensor is now calibrated and ready for measurements [6]

Sensor Diagnostic and Troubleshooting Workflow

Redox Sensor Diagnostic and Maintenance Workflow

Advanced Applications in Biosensor Arrays

High-Resolution Sensor Arrays

Recent advances in redox sensor technology have enabled the development of high-resolution arrays for specialized applications. For example, potentiometric redox sensor arrays with 23.5-μm resolution have been fabricated for real-time neurotransmitter imaging. These 128×128 pixel arrays based on charge-transfer-type potentiometric sensors can visualize the distribution of glutamate at concentrations as low as 1 μM, demonstrating feasibility as a high-resolution bioimaging technique for studying neurochemical dynamics [3].

Integration with Enzymatic Systems

Redox biosensors often incorporate enzymatic systems for specific molecular detection. A common configuration involves:

- Primary enzyme: Targets the analyte of interest (e.g., glutamate oxidase for glutamate)

- Secondary enzyme system: Often horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to process reaction products

- Electron mediator: Ferrocene derivatives that shuttle electrons between enzymes and electrodes

The general reaction scheme for glutamate detection exemplifies this approach:

Where Fc and Fc⺠represent ferrocene in reduced and oxidized states, respectively [3].

Quality Control and Validation Metrics

Table 3: Acceptance Criteria for Redox Sensor Performance

| Performance Parameter | Acceptable Range | Ideal Value | Corrective Action if Out of Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (mV/pH unit) | 55-60 mV | 59 mV | Clean and recondition sensor [5] |

| mV span between buffers | 160-180 mV | 177 mV | Clean sensor and recalibrate [5] |

| Response time in buffers | <90 seconds | <60 seconds | Clean sensor; check for aging [5] |

| Stabilization time in new media | <30 minutes | <15 minutes | May be normal for media transitions [7] |

| Sensor lifetime | 12-24 months | >18 months | Plan replacement as sensor ages [5] [7] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of redox probe electrochemistry continues to evolve with several promising directions:

- Closed-loop bio-electronic systems: Integrating redox-based communication between biological systems and electronics for bidirectional information transfer [4]

- Miniaturized sensor arrays: Developing higher density arrays with improved spatial resolution for mapping chemical distributions

- Advanced calibration models: Implementing sophisticated calibration approaches like the SCARE model that balance accuracy, real-time performance, and efficiency through sequence compression and bitwise attention mechanisms [8]

- Virtual in-situ calibration: Using computational methods combined with Bayesian inference to diagnose and calibrate sensor faults in operational systems [9]

These advancements are enhancing our ability to create more reliable, sensitive, and robust redox-based biosensing platforms for both fundamental research and applied analytical applications.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Researchers often encounter specific challenges when working with redox biosensor arrays. The table below outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions to ensure data integrity and sensor performance.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable readings or high signal drift [10] | - Depleted or diluted reference electrolyte.- Contamination on the electrode surface.- Low electrolyte level in the reference cell. | - Recalibrate and potentially replace the electrode [10].- Clean the electrode surface mechanically (e.g., soft-bristle brush, fine sandpaper) or chemically [10].- Verify electrolyte level is at least ½" (1.27 cm) remaining [10]. |

| Decreased sensitivity and accuracy over time (in vivo) [11] | - Enzyme degradation on the sensing electrode.- Biofouling or tissue reaction from implantation.- Signal interference from the complex biological environment. | - Implement a self-calibrating device architecture to correct for signal decay [11].- Use nanostructured coatings (e.g., CNTs, conductive polymers) to enhance enzyme stability and sensitivity [11]. |

| Low signal output or poor limit of detection (LOD) [3] | - Inefficient electron transfer between the biorecognition element and the electrode. | - Employ an efficient electron mediator (e.g., ferrocene) [3].- Optimize the oxidation state of the mediator to lower the LOD [3]. |

| Physical damage to sensitive layers [12] | - Mechanical damage during sensor insertion (e.g., for microneedle arrays). | - Design redundant sensing arrays with multiple independent working electrodes to compensate for individual sensor failure [12]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most reliable method to check the health of my redox electrode?

For conductivity electrodes, the best practice is to regularly calibrate and calculate the slope and offset; a slope error beyond ±15% typically indicates an issue [10]. For ORP electrodes, which are often calibrated with a single buffer, health is assessed by observing the stability of the reading in a calibration solution. Increasing drift rates signal that the electrolyte is depleting and the electrode may need replacement [10].

Q2: How can I monitor redox changes in living cells without disrupting them?

Genetically encoded biosensors like roGFP (redox-sensitive Green Fluorescent Protein) are ideal for this. roGFP can be targeted to specific cellular compartments (e.g., mitochondria) and provides real-time, ratiometric readouts of the redox state within living cells, making it minimally invasive and highly specific [13].

Q3: Our research requires multiplexed monitoring of biomarkers in vivo. How can we overcome signal instability?

A promising solution is the use of a self-calibrating multiplexed microneedle electrode array (SC-MMNEA). This design uses discrete microneedles for each analyte (e.g., glucose, lactate, ions) and incorporates a microfluidic delivery module for self-calibration. This in-situ calibration corrects for signal drift caused by enzyme degradation or tissue variation, significantly enhancing reliability for long-term studies [11].

Q4: What are the advantages of potentiometric sensor arrays for high-resolution redox imaging?

Potentiometric sensors, unlike amperometric ones, measure interfacial potential, a signal that does not inherently decrease with electrode size. This makes them exceptionally suited for miniaturization into high-density arrays, enabling high-spatial-resolution imaging of redox species without sacrificing the signal-to-noise ratio [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Mechanical Cleaning of Electrodes

Proper cleaning is essential for maintaining electrode performance and accurate measurements [10].

1. Prepare Cleaning Solution:

- Add a mild detergent (e.g., hand soap) to water.

2. Clean the Electrode:

- Dip a soft-bristle brush into the solution.

- For ORP Electrodes: Vigorously scrub the platinum bands, taking care not to break the bulb. Fine wet sandpaper or steel wool can be used, focusing abrasion on the platinum band itself [10].

- For Conductivity Electrodes: Scrub the four round cells and the inside of the electrode guard. Ensure the plastic housing is clean to prevent air bubble entrapment [10].

3. Verify Cleanliness and Recalibrate:

- Rinse the electrode thoroughly with deionized water.

- Recalibrate the sensor and verify that performance metrics (e.g., slope error for conductivity, drift rate for ORP) are within acceptable ranges [10].

Protocol: Immobilization of Enzymes for Redox Sensing

This protocol details the creation of a functional biorecognition layer on a gold electrode array using a poly-ion-complex (PIC) membrane, as used in high-resolution glutamate sensing [3].

Materials:

- Poly-L-lysine (PLL)

- Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS)

- Relevant enzyme (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), Glutamate Oxidase (GluOx))

- Deionized Water (DIW)

Method (Layer-by-Layer Deposition):

- Apply Polycation Layer: Drop 10 µL of 60 mM PLL solution onto the sensing area and dry for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- Immobilize Enzyme Layer: Drop an enzyme solution (e.g., containing 10 units of HRP and/or GluOx) onto the surface and dry overnight at 4 °C.

- Apply Polyanion Layer: Drop 10 µL of 75 mM PSS solution and dry for 1 hour at room temperature [3].

This PIC membrane securely entraps the enzymes, creating a stable, biocompatible sensing interface.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Redox Sensing Pathway for Glutamate

Workflow for Sensor Calibration and In-Vivo Monitoring

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions for developing and working with redox biosensor arrays.

| Item | Function / Role in Redox Biosensing |

|---|---|

| Glutamate Oxidase (GluOx) | A key biorecognition element that catalyzes the oxidation of glutamate, producing hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) as a byproduct [3]. |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | An enzyme used in tandem with oxidases; it catalyzes the reduction of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, often facilitating the oxidation of an electron mediator [3]. |

| Ferrocene (Fc)/Ferrocene Methanol (FcMeOH) | An electron mediator that shuttles electrons between the enzyme's redox center and the electrode surface, enhancing signal and lowering the limit of detection [3]. |

| roGFP (redox-sensitive GFP) | A genetically encoded biosensor that reports the cellular redox state via a ratiometric fluorescence change, allowing real-time monitoring in living cells [13] [14]. |

| Poly-ion-complex (PIC) Membrane | A stable matrix (e.g., of PLL and PSS) for entrapping and immobilizing enzymes on the electrode surface, preserving their activity [3]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) & Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Nanomaterials used to coat electrodes, providing a high surface area that enhances electron transfer efficiency, sensor sensitivity, and stability [11]. |

| Potassium Ferricyanide/Ferrocyanide (K₃Fe(CN)₆ / K₄Fe(CN)₆) | A standard redox couple used for characterizing the fundamental redox response and sensitivity of a newly fabricated sensor [3]. |

| AT2R-IN-1 | AT2R-IN-1, CAS:2896132-06-0, MF:C21H27FN8, MW:410.5 g/mol |

| 2-MeS-ATP | 2-MeS-ATP, MF:C11H18N5O13P3S, MW:553.28 g/mol |

Performance Data and Calibration Standards

Redox Sensor Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes key performance parameters for redox sensors as reported in recent literature, providing benchmarks for experimental validation.

| Sensor Type / Target Analyte | Redox Sensitivity | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometric Array (with Fc) [3] | 49.9 mV/dec | -- | Response to Fe(CN)₆³â»/â´â» redox couple. |

| Potentiometric Array for H₂O₂ [3] | 44.7 mV/dec | 1 µM | Uses HRP enzyme and ferrocene mediator. |

| Potentiometric Array for Glutamate [3] | ~44.7 mV/dec | 1 µM | Uses GluOx enzyme; comparable performance to H₂O₂ sensor. |

| Self-Calibrating Multiplexed MN Array [11] | -- | -- | Monitors 9 analytes (e.g., glucose, ions, ROS); in-vivo accuracy improved by self-calibration. |

This technical support guide provides essential troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers working with Faradaic and Non-Faradaic signal transduction processes, particularly within the context of developing and calibrating redox biosensor arrays. The accurate interpretation of these distinct electrochemical signals is fundamental to advancing research in drug development, diagnostic biosensors, and metabolic monitoring.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between Faradaic and Non-Faradaic signal transduction?

Faradaic and Non-Faradaic processes describe two different types of interactions at an electrode-electrolyte interface. Faradaic processes involve actual electron transfer across the electrode surface, leading to the oxidation or reduction of electroactive species [15]. This is the basis for detecting specific biomarkers like dopamine, glucose, or hydrogen peroxide through redox reactions [15] [16]. In contrast, Non-Faradaic processes do not involve net electron transfer. Instead, they rely on the physical rearrangement of ions at the electrode interface, which changes the interfacial capacitance and is measured as an impedance change [15]. This makes Non-Faradaic methods ideal for label-free detection of biomolecular binding events, such as the adsorption of proteins or DNA [15].

2. Why is calibration critical for redox biosensor arrays, and what are the common challenges?

Calibration is essential because the raw signals from biosensors, especially those based on optical readouts like FRET (Förster Resonance Energy Transfer), are highly sensitive to imaging conditions such as laser intensity and detector sensitivity [17]. Without proper calibration, it is difficult to compare results across different experiments or sessions, leading to unreliable data. Key challenges include:

- Signal Drift: Enzyme-based sensing electrodes can see decreased signal stability over time due to enzyme degradation in complex biological environments [11].

- Imaging Variability: Fluctuations in excitation light or photobleaching can obscure the reciprocal changes in donor and acceptor fluorescence that indicate a true FRET response [17].

- Crosstalk: In multiplexed arrays, signals from different sensing electrodes or fluorescence channels can interfere with one another [11].

3. How can I troubleshoot a biosensor showing a low signal-to-noise ratio in Non-Faradaic EIS measurements?

A low signal-to-noise ratio in Non-Faradaic Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) often points to issues at the electrode-solution interface. Consider these steps:

- Verify Electrode Surface: Ensure the bio-recognition element (e.g., antibody, aptamer) is properly immobilized on the electrode. Contamination or incomplete coverage can severely dampen the capacitive signal.

- Check Ionic Strength: The composition and concentration of the electrolyte solution significantly impact the formation of the electrical double layer. Use a consistent, buffered electrolyte to maintain stable conditions.

- Confirm Circuit Model: Fit your EIS data to an equivalent circuit model. An unexpectedly low charge-transfer resistance might indicate a faulty electrode or the presence of an undesired Faradaic leak.

4. What does it mean if my Faradaic sensor shows a high background current?

A high background current in a Faradaic sensor typically indicates non-specific reactions or interference.

- Identify Interferents: The working electrode might be reacting with other electroactive species in the sample matrix. For example, in biological fluids, ascorbic acid or uric acid can be oxidized at similar potentials to your target analyte.

- Improve Specificity: Incorporate protective membranes or use surface modifications that repel interfering substances. The use of specific ionophores in potentiometric sensors is one such strategy [18].

- Check the Reference Electrode: An unstable or degraded reference electrode can lead to drifting and inaccurate background currents.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent FRET Biosensor Readings Across Imaging Sessions

Issue: Measurements for a genetically encoded FRET biosensor cannot be replicated reliably from one experiment to the next.

Solution: Implement a calibration protocol using FRET standards to normalize the acceptor-to-donor signal ratio [17].

- Step 1: Prepare control cells expressing "FRET-ON" and "FRET-OFF" standard constructs. These are engineered proteins where the FRET efficiency is locked at a high or low value, respectively [17].

- Step 2: In every imaging session, include these control cells alongside your experimental biosensor cells.

- Step 3: Acquire your FRET data as usual.

- Step 4: Use the signals from the FRET-ON and FRET-OFF standards to normalize your experimental biosensor's FRET ratio. This corrects for day-to-day variations in laser power, detector sensitivity, and other imaging parameters [17].

- Step 5: For absolute quantification, also image donor-only and acceptor-only cells to calculate crosstalk coefficients and determine the actual FRET efficiency [17].

Problem 2: Signal Instability in a Multiplexed Electrochemical Biosensor Array

Issue: Signals from a wearable or implantable multiplexed sensor array (e.g., for glucose, lactate, ions) drift over time, reducing accuracy.

Solution: Integrate a self-calibration mechanism to correct for signal decay in real-time [11].

- Step 1: Design a device with discrete microneedle (MN) electrodes, each functionalized for a specific analyte (e.g., glucose, cholesterol, Na+, K+, Ca2+, pH) [11].

- Step 2: To address signal decay from enzyme degradation or tissue variation, create a self-calibration module. This can involve the controlled delivery of a standard solution via a hollow MN to the sensing site [11].

- Step 3: Periodically, the device releases the standard solution and records the sensor's response. This in-situ measurement provides a reference point to recalibrate the sensor's signal, correcting for drift without requiring invasive blood sampling [11].

- Step 4: Use nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and conductive polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) to coat the MN electrodes. This enhances the electron transfer efficiency and improves the sensor's sensitivity and stability over time [11].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Differentiating Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes via EIS

This protocol is used to characterize a new electrode surface for a biosensor.

1. Electrode Preparation: Functionalize a gold electrode with your chosen biorecognition element (e.g., a thiol-modified aptamer). Use a bare gold electrode as a control.

2. EIS Measurement Setup:

- Instrument: Potentiostat with EIS capabilities.

- Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system (working, counter, and reference electrodes) in a solution containing a redox probe like [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â».

- Parameters: Apply a small AC voltage amplitude (e.g., 10 mV) over a wide frequency range (e.g., 0.1 Hz to 100,000 Hz) at the open circuit potential.

3. Data Analysis:

- Faradaic EIS: In the presence of the redox probe, the electron transfer process will dominate, and the resulting Nyquist plot will show a semicircle (characterizing charge-transfer resistance, Rct) at high frequencies followed by a linear region (Warburg impedance, Zw) at low frequencies [15].

- Non-Faradaic EIS: In the absence of a redox probe, the system is "blocking" and the dominant element is the double-layer capacitance (Cdl). The Nyquist plot will appear as a near-vertical line [15].

The workflow for this experimental setup is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Calibration of a Potentiometric Ion Sensor (Non-Faradaic)

This protocol details the calibration of a textile-based ion sensor, such as those integrated into a multi-biosensing hairband [18].

1. Sensor Preparation: Use a weavable biosensor array fabricated via coaxial wet spinning, functionalized with ion-selective ionophores for Na+, K+, or Ca2+ [18].

2. Calibration Setup:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target ion.

- Immerse the sensor and a reference electrode in each solution, from lowest to highest concentration.

3. Measurement:

- For each standard solution, measure the steady-state potential (in mV) between the sensor and the reference electrode.

- Allow the signal to stabilize at each concentration before recording.

4. Data Analysis:

- Plot the measured potential (mV) against the logarithm of the ion concentration.

- Fit a linear regression to the data. The slope of the line is the sensitivity of the sensor (e.g., mV/decade), and the intercept is used for determining unknown concentrations [18].

The quantitative performance of state-of-the-art biosensors is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Biosensors from Literature

| Biosensor Type / Analyte | Transduction Mechanism | Sensitivity | Stability (Signal Drift) | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Textile-based Ion Sensor [18] | Potentiometric (Non-Faradaic) | 56.33 mV/decade (Na+) | 0.17 mV/h | Multi-biosensing hairband for sweat analysis |

| Textile-based pH Sensor [18] | Potentiometric (Non-Faradaic) | 39.52 mV/pH | 0.13 mV/h | Multi-biosensing hairband for sweat analysis |

| FRET Biosensors [17] | Optical (FRET efficiency) | N/A (Ratio-based) | Corrected via calibration | Live-cell imaging of biochemical activities |

| Multiplexed MN Electrode [11] | Amperometric (Faradaic) & Potentiometric | Varies by analyte (e.g., Glucose) | Corrected via self-calibration | Subcutaneous monitoring in a rat model |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Biosensor Development and Calibration

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| FRET Standard Constructs ("FRET-ON/OFF") [17] | Calibrating optical biosensors; normalizing FRET ratios across imaging sessions. | Genetically encoded proteins with locked high or low FRET efficiency. |

| Ion-Selective Ionophores | Biorecognition element in potentiometric sensors for specific ions (Na+, K+, Ca2+) [18]. | Provides high selectivity for the target ion over interferents. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Electrode nanomaterial; enhances electron transfer and surface area [11]. | High conductivity and large specific surface area improve sensor sensitivity. |

| Conductive Polymer (PEDOT:PSS) | Electrode coating; improves stability and biocompatibility of implantable sensors [11]. | Combines electrical conductivity with mechanical flexibility and stability in vivo. |

| Redox Probe ([Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») | Enables Faradaic EIS characterization of electrode surfaces and electron transfer kinetics [15]. | Reversible redox couple for reliable electrochemical testing. |

| Zaladenant | Zaladenant, CAS:2246426-52-6, MF:C19H15F3N6O, MW:400.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Stat5-IN-3 | Stat5-IN-3, MF:C25H27N5O, MW:413.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Role of Electrolytes and Ionic Strength in Signal Generation

In the context of calibrating redox biosensor arrays, the electrolyte solution and its ionic strength are not merely a background medium; they are active and critical components in the signal generation process. The electrolyte facilitates charge transport, influences the electrical double layer at the electrode-solution interface, and directly affects the activity of ions and electroactive species. Ionic strength, a measure of the total ion concentration in solution, can significantly alter the stability, sensitivity, and reproducibility of biosensor signals by modulating electrochemical potentials, reaction kinetics, and the stability of biomolecules like enzymes. A profound understanding of these factors is essential for developing robust calibration protocols and troubleshooting erratic sensor performance [19] [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental role of an electrolyte in an electrochemical biosensor? The electrolyte, typically a solution containing dissolved salts, provides the ionic conductivity necessary for closing the electrical circuit within an electrochemical cell. It enables the flow of current between the working, reference, and counter electrodes. Furthermore, the ions in the electrolyte form a structured layer at the electrode surface, known as the electrical double layer (EDL), which is critical for the stability of the interfacial potential and the kinetics of electron transfer reactions. Without a suitable electrolyte, signal generation in a biosensor would be inefficient or non-existent [21].

Q2: How does ionic strength specifically influence signal generation? Ionic strength exerts its influence through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Ion Activity and Double Layer Compression: Higher ionic strength decreases the activity coefficients of ions, which can shift electrochemical potentials [19]. It also compresses the EDL, reducing its thickness. This can decrease charge-transfer resistance and alter the rate of electron transfer for surface-bound reactions.

- Biomolecule Stability: Enzymes and other biorecognition elements immobilized on the sensor surface can be sensitive to the ionic environment. Non-physiological ionic strength can lead to denaturation, loss of activity, or undesirable conformational changes, thereby diminishing the signal.

- Redox Mediator Behavior: For biosensors relying on mediated electron transfer, the redox mediator's potential and electron transfer kinetics can be a function of the ionic strength, directly impacting the catalytic current.

Q3: Why is a three-electrode system preferred over a two-electrode system for precise biosensor calibration? A three-electrode system (working, reference, counter) separates the function of potential measurement from current flow. This ensures accurate control and measurement of the working electrode's potential versus a stable reference, independent of the current or solution resistance. In a two-electrode system, where the counter electrode also acts as the reference, the current passage can polarize the reference, causing its potential to drift and leading to inaccurate potential control and unstable signals, which is detrimental for quantitative calibration [21] [22].

Q4: My biosensor signal is noisy. Could the electrolyte be a cause? Yes. Common electrolyte-related issues causing noise include:

- Low Ionic Strength: Solutions with low conductivity (high resistance) are prone to increased thermal noise and can make the system more susceptible to external electromagnetic interference.

- Contaminated Electrolyte: Impurities can introduce parasitic redox reactions, leading to unstable background currents.

- Blocked Reference Electrode Frit: A clogged frit in a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) creates a high impedance path, resulting in erratic potential readings and noisy data. Always ensure the reference electrode is functioning correctly [23] [22].

Q5: How can ionic strength be leveraged to improve biosensor performance? Strategic manipulation of ionic strength can be a powerful tool:

- Optimizing Electron Transfer: For systems with sluggish electron transfer, increasing ionic strength can compress the double layer and enhance electron tunneling rates.

- Shielding Biomolecules: Incorporating enzymes within protective matrices like biomineralized metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) can shield them from harsh ionic environments, improving stability against substrate inhibition and thermal inactivation, thereby expanding the sensor's linear detection range [20].

- Reducing Non-Specific Adsorption: Adjusting ionic strength can sometimes be used to minimize the non-specific adsorption of interfering proteins or molecules onto the electrode surface.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Signal Instability and Noise

Signal instability, drift, or excessive noise are common problems that often originate from the electrochemical setup or the electrolyte solution.

Guide 2: Addressing Low or No Signal Response

A weak or absent signal indicates a failure in the electron transfer pathway or a deactivated biological component.

Data Presentation: Ionic Strength Effects

Table 1: Impact of Ionic Strength on Key Biosensor Parameters

| Parameter | Low Ionic Strength Effect | High Ionic Strength Effect | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Decreased (higher noise) due to increased solution resistance [23] [22] | Can be improved, but excessively high levels may cause non-specific effects | Gradually increase salt concentration (e.g., KCl, PBS) while monitoring background current and noise. |

| Redox Potential | Can shift due to higher ion activity coefficients [19] | Stabilizes; follows theoretical predictions more closely in concentrated electrolytes [19] | Use a supporting electrolyte at a consistent, sufficiently high concentration (e.g., 0.1 M) to swamp out variable ionic contributions from the sample. |

| Biomolecule Stability | May be sub-optimal for some enzymes | Can lead to denaturation or loss of activity for sensitive enzymes [20] | Use biocompatible buffers at physiological ionic strength (~150 mM). Consider protective matrices like ZIF-8 MOFs for encapsulation [20]. |

| Electron Transfer Kinetics | Can be slower due to a more diffuse double layer | Generally faster due to a compressed double layer and reduced charge-transfer resistance | If electron transfer is slow, a moderate increase in ionic strength may improve sensor response. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Electrolyte and Signal Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Biosensor Development | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Standard physiological electrolyte; provides pH buffering and ionic strength. | Consistently used at 0.01 M (low) to 0.1 M (standard) to maintain biomolecule integrity and stable electrochemistry. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Inert supporting electrolyte to control ionic strength without specific biochemical effects. | Commonly used in concentrations from 0.1 M to 1.0 M to minimize solution resistance and define the electrical double layer [19]. |

| Redox-Active Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs) | Protective biomineralized matrix for enzyme encapsulation. | Shields enzymes from substrate inhibition and thermal inactivation (e.g., up to 50°C), expanding linear detection range (e.g., from 0.1 to 0.5 mmol Lâ»Â¹ for peroxidase) [20]. |

| Benzothiazoline-based Redox Mediator | Electron shuttle for mediated electron transfer within insulating frameworks. | Essential to overcome the insulating barrier of crystalline ZIF matrices and enable bioelectrocatalysis when co-encapsulated with the enzyme [20]. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for accurate control of the working electrode. | Ensure the frit is not clogged and the inner fill solution is uncontaminated and at the correct concentration to prevent unstable potentials [23] [22]. |

Interplay Between Redox Probes and Background Electrolytes

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Observed | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Method | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or No Signal Response | Degradation of redox probe; Insufficient ionic strength [24]. | Measure solution conductivity; Perform cyclic voltammetry to check redox activity. | Prepare fresh redox probe stock; Increase background electrolyte concentration [24]. |

| High Signal Noise/Instability | Non-optimal redox probe concentration; Electrode fouling [24]. | Visual inspection of Nyquist plot for inconsistent semicircles. | Lower redox probe concentration; Use buffered electrolyte (e.g., PBS); Clean/re-polish electrodes [24]. |

| Poor Sensor Sensitivity/Gain | Mismatch between calibration and measurement conditions (temperature, media) [25]. | Compare calibration curves collected at different temperatures. | Calibrate at the same temperature as measurement (e.g., 37°C for in vivo); Use freshly collected biological media [25]. |

| Inaccurate Concentration Readouts | Signal drift from enzyme degradation (in enzyme-based sensors); Tissue variation around implanted sensor [11]. | Track sensor signal decay over time against reference standards. | Implement a self-calibration system, such as MN-delivery-mediated calibration [11]. |

| Overlapping RC Semicircles in EIS | Redox species and background electrolyte have similar time constants, causing their Nyquist semicircles to merge [24]. | EIS analysis at varying redox concentrations or ionic strengths. | Adjust ionic strength of background electrolyte or concentration of redox probe to separate the semicircles [24]. |

Advanced Diagnostic: EIS Nyquist Plot Interpretation

| Nyquist Plot Feature | Underlying Cause | Impact on Biosensor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Two Distinct Semicircles | Well-separated charge transfer processes from the electrolyte and the redox probe [24]. | Easier to monitor specific biorecognition events; Enhanced signal clarity and stability. |

| Single, Merged Semicircle | Overlapping time constants between the redox probe reaction and the background electrolyte's charge transfer [24]. | Difficult to deconvolute specific signal changes; Leads to poor sensitivity and inaccurate quantification. |

| Semicircle Shift to Higher Frequencies | Increased ionic strength of the background electrolyte or increased concentration of the redox probe [24]. | Can be used strategically to separate overlapping signals and optimize the sensor's frequency response. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the choice of background electrolyte important in a Faradaic biosensor? The background electrolyte provides the necessary ionic conductivity for the electrochemical cell to function. Its properties, such as ionic strength, pH, and the specific cations/anions present, significantly affect how redox probe molecules interact with the electrode surface. This interaction directly controls the impedimetric signal, influencing the sensor's sensitivity and stability [24].

Q2: How does ionic strength specifically affect the signal from my redox probe? Increasing the ionic strength of the background electrolyte (e.g., using PBS with high salt concentration) causes the resistive-capacitive (RC) semicircle in a Nyquist plot to move to higher frequencies. This can be used to resolve an overlapping signal from the redox probe, thereby cleaning up the signal and reducing noise, which is particularly beneficial when using lower-cost instrumentation [24].

Q3: My research involves in vivo sensing. What is the critical factor for accurate calibration? Matching the temperature of your calibration media to the actual measurement temperature is critical. Calibration curves collected at room temperature can differ significantly from those at body temperature (37°C), leading to substantial underestimation or overestimation of target concentrations. For the highest accuracy, calibration should be performed in freshly collected, body-temperature blood [25].

Q4: What can I do if my sensor signal degrades over long-term implantation? Enzyme degradation and tissue variation around the sensor are common causes. A promising solution is the use of a self-calibrating microneedle (MN) electrode array. This technology uses an integrated calibration module to correct signals in vivo without the need for painful and invasive blood sampling, thereby maintaining long-term accuracy [11].

Q5: Should I use a simple salt like KCl or a buffered solution like PBS as my background electrolyte? While both are valid, a buffered electrolyte like PBS often provides a lower standard deviation in the measured signal. However, it may also lead to lower overall sensitivity. The choice involves a trade-off: PBS offers better signal stability, while KCl might provide a higher signal gain that requires more careful interpretation [24].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and their critical functions for experiments investigating the interplay between redox probes and background electrolytes.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the System | Example & Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Probe Pairs | Generates Faradaic current at the electrode surface, enhancing the impedimetric signal from biorecognition events [24]. | Ferro/Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]â´â»/³â»); Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) ([Ru(bpy)₃]²âº). Concentration must be optimized to prevent signal overlap with the electrolyte [24]. |

| Buffered Electrolyte | Provides stable pH and ionic strength; reduces signal standard deviation compared to non-buffered salts [24]. | Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS). Offers a stable chemical environment but may slightly reduce sensitivity [24]. |

| Chloride-based Salt | Provides high ionic conductivity without buffering capacity, potentially leading to higher signal gain [24]. | Potassium Chloride (KCl). Useful for fundamental studies of redox-electrode interactions without pH control [24]. |

| Ionic Liquid Additive | Enhances ionic conductivity and stabilizes the electrochemical interface in polymer-based or non-aqueous systems [26]. | 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium-tetrafluoroborate (BMIMBFâ‚„). Used as a non-volatile, non-flammable plasticizer in polymer electrolytes [26]. |

| Polymer Electrolyte Matrix | Serves as a solid or gel scaffold for ions, enabling the creation of membrane-free or specialized biphasic battery systems [26]. | Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF); Polypropylene carbonate (PPC). Offers wide voltage windows and tunable ionic conductivity [26]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Electrolyte and Redox Probe Concentrations

Aim: To systematically find the optimal combination of background electrolyte ionic strength and redox probe concentration that minimizes signal noise and separates the redox probe's signal from the background for a Faradaic EIS biosensor [24].

Materials:

- Impedance Analyzer (e.g., Keysight 4294A or Analog Discovery 2)

- Electrochemical cell with appropriate electrodes (e.g., interdigitated microelectrodes)

- Redox probe stock solutions: e.g., 100 mM Potassium ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) / potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) mixture (1:1) in DI water [24].

- Background electrolyte stock: e.g., 1 M Potassium Chloride (KCl) or 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [24].

- DI water

Procedure:

- Prepare Electrolyte-Redox Matrix: Create a series of solutions with a fixed concentration of the redox probe (e.g., 1 mM) while varying the concentration of the background electrolyte (e.g., 10 mM, 50 mM, 100 mM, 500 mM KCl). In a second series, fix the background electrolyte concentration (e.g., 100 mM PBS) and vary the redox probe concentration (e.g., 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 5 mM) [24].

- Baseline EIS Measurement: Place the bare electrodes in the electrochemical cell. Add the first solution. Allow the system to equilibrate for 2 minutes.

- Run Impedance Scan: Perform an EIS measurement over a suitable frequency range (e.g., 100 Hz to 1 MHz) with a small applied voltage (e.g., 10 mV). Record the Nyquist plot.

- Repeat Measurements: Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with DI water between measurements. Repeat steps 2-3 for all solutions in your matrix.

- Data Analysis: For each Nyquist plot, note the number of visible semicircles and the frequency at which the dominant semicircle appears. The optimal condition is typically identified as the one where the redox probe's semicircle is distinct and the signal demonstrates low standard deviation across replicates [24].

Core Concepts and Workflow Visualization

Signal Optimization Logic

Calibration Protocol Flow

Establishing Robust Calibration Methodologies: From Standard Curves to Point-of-Care Systems

Step-by-Step Protocol for Generating a Redox Calibration Curve

This guide provides a detailed protocol for generating a redox calibration curve, a critical procedure for quantifying the nominal concentration of metabolic fluorophores like NADH (reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) and Fp (oxidized flavoproteins) in biological tissues. This calibration is essential for converting relative fluorescence intensity measurements from redox scanning into quantitative concentration values, enabling accurate assessment of mitochondrial redox states in research areas such as cancer metabolism and drug development [27].

Proper calibration allows for the direct comparison of redox ratio images (e.g., Fp/(Fp+NADH)) obtained at different times or with different instrument settings, independent of variations in hardware configuration [27]. The following protocol, based on the quantitative redox scanning method, outlines the preparation of standard solutions, tissue sample handling, and data analysis to achieve reliable quantification.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a calibration curve necessary for redox scanning? A calibration curve is fundamental because it converts relative fluorescence signal intensities into quantitative, instrument-independent concentration values. Without calibration, signal intensities depend heavily on specific instrument settings such as filter configurations, PMT dynamic range, and lamp condition, making it difficult to compare data from different experimental sessions or across different laboratories. Calibration using standards of known concentration allows for the determination of the nominal NADH and Fp concentration in tissues, facilitating valid comparisons [27].

Q2: What is the linear dynamic range of the redox scanner for NADH and Fp? The redox scanner exhibits a very good linear response within specific concentration ranges for the standard solutions. The validated ranges are [27]:

- NADH: 165 μM to 1318 μM

- FAD (as a key Fp): 90 μM to 720 μM It is recommended to prepare standard solutions that fall within these ranges to ensure accurate quantification.

Q3: How does temperature affect the calibration process? Matching the temperature of calibration to the intended measurement conditions is critical for accuracy. Research on electrochemical aptamer-based biosensors has demonstrated that calibration curves can differ significantly between room temperature and body temperature (37°C). Using a calibration curve collected at the wrong temperature can lead to substantial under- or over-estimation of target concentrations [25]. For the redox scanner protocol provided, all steps following snap-freezing are conducted at liquid nitrogen temperature to maintain sample integrity and signal enhancement [27].

Q4: What are common sources of error in generating the calibration curve, and how can they be avoided? Common errors and their mitigations are listed in the table below.

Table: Troubleshooting Common Calibration Errors

| Error Source | Impact on Results | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate standard solution preparation | Non-linear or inaccurate calibration curve | Use high-precision balances and calibrated pipettes. Verify stock concentrations with a UV-Vis spectrometer [27]. |

| Incomplete or uneven snap-freezing | Inhomogeneous fluorescence signal from standards | Ensure standards and tissues are fully submerged in liquid nitrogen for rapid, homogeneous freezing [27]. |

| Signal saturation during scanning | Loss of quantitative data in saturated regions | Use proper neutral density (ND) filters on the emission channels to keep the signal within the PMT's linear detection range [27]. |

| Drift in instrument response | Decreased accuracy over time | Implement a rigorous instrument maintenance and quality control schedule. Regularly scan reference standards to monitor performance. |

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents are essential for executing the protocol.

Table: Essential Reagents and Their Functions

| Reagent | Function in the Protocol | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NADH (Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, reduced disodium salt) | Primary fluorophore standard for calibration curve | Prepare stock solution in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0. Determine concentration using ε = 6,220 Mâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹ at 360 nm [27]. |

| FAD (Riboflavin 5'-adenosine diphosphate disodium salt) | Primary oxidized flavoprotein standard for calibration curve | Prepare stock solution in Hanks balanced salt solution. Determine concentration using ε = 11,300 Mâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹ at 450 nm [27]. |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (10 mM, pH 8.0) | Solvent for NADH standard solutions | Provides a stable pH environment for NADH [27]. |

| Hanks Balanced Salt Solution | Solvent for FAD standard solutions | A physiological salt solution for FAD [27]. |

| Mounting Buffer (Ethanol-Glycerol-Water, 10:30:60) | Medium for embedding samples and standards | Has a freezing point of -30°C, which strengthens the sample matrix for grinding and scanning at low temperatures [27]. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Part 1: Preparation of NADH and FAD Solution Standards

Prepare Stock Solutions:

- Weigh out the appropriate amounts of NADH and FAD powder.

- Dissolve NADH in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) to create a stock solution. Confirm the concentration spectrophotometrically using an extinction coefficient (ε) of 6,220 Mâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹ at 360 nm. A typical stock concentration is 1,318 μM [27].

- Dissolve FAD in Hanks balanced salt solution to create a stock solution. Confirm the concentration using ε = 11,300 Mâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹ at 450 nm. A typical stock concentration is 719 μM [27].

Perform Serial Dilutions:

- Perform serial dilutions of the NADH and FAD stock solutions to create at least four standard solutions each, covering the linear range of the instrument (e.g., 165–1318 μM for NADH; 90–720 μM for FAD) [27].

Assemble Standard Matrix:

- Inject each standard solution and a buffer-only control into individual 1/8-inch Teflon tubes (approximately 1 cm long, one sealed-end).

- Mount these tubes in a 3x3 matrix within a plastic screw closure (2.4 cm diameter) using play-dough at the base [27].

Snap-Freeze Standards:

- Snap-freeze the entire assembly by fully submerging it in liquid nitrogen. This ensures rapid and homogeneous freezing.

- Strengthen the matrix by adding pre-chilled mounting buffer to the closure, then re-immerse in liquid nitrogen for consolidation and storage until scanning [27].

Part 2: Preparation of Tissue Samples with Reference Standards

Snap-Freeze Tissue:

- For in vivo metabolic state preservation, anesthetize the animal and snap-freeze the tissue of interest in situ using liquid nitrogen.

- Excise the frozen tissue rapidly in a low-temperature environment and keep it immersed in liquid nitrogen [27].

Embed Sample with Standards:

- Place mounting buffer in a plastic closure and chill it with liquid nitrogen until firm.

- Position the snap-frozen tissue sample in the chilled mounting medium.

- Quickly insert reference Teflon tubes containing a known NADH standard and a known FAD standard adjacent to the tissue sample.

- Cover the sample and standards with more chilled mounting buffer and dip the entire closure into liquid nitrogen for consolidation [27].

Part 3: Redox Scanning and Data Acquisition

Sample Surface Preparation:

- Mount the prepared sample in the redox scanner at liquid nitrogen temperature.

- Use the integrated grinder to mill the sample surface flat under liquid nitrogen [27].

Configure Instrumentation:

- The redox scanner typically uses a mercury arc lamp, a bifurcated fiber-optic probe for excitation and emission, and a photomultiplier tube (PMT) for detection.

- Set the appropriate filters [27]:

- NADH channel: Excitation 360±26 nm, Emission 430±25 nm.

- Fp channel: Excitation 430±25 nm, Emission 525±32 nm.

- If the signal is saturated, insert neutral density (ND) filters into the emission path.

Acquire Fluorescence Images:

- Scan the sample surface, which includes both the tissue and the adjacent standard solutions, to acquire fluorescence images for both NADH and Fp channels [27].

Part 4: Data Analysis and Calibration Curve Generation

Extract Mean Fluorescence Intensities:

- From the scanned images, measure the mean fluorescence intensity for each standard solution in both the NADH and Fp channels.

Generate Calibration Curves:

- Plot the mean fluorescence intensity against the known concentration for each NADH and FAD standard.

- Perform linear regression analysis to obtain the slope and intercept for both NADH and Fp.

- The linear equations (Fluorescence = Slope × Concentration + Intercept) form your calibration curves [27].

Quantify Tissue Fluorophore Concentrations:

- Measure the mean fluorescence intensity of the tissue regions in both channels.

- Use the calibration curve equations to calculate the nominal concentrations of NADH and Fp in the tissue:

[NADH]_tissue = (Fluorescence_NADH_tissue - Intercept_NADH) / Slope_NADH[Fp]_tissue = (Fluorescence_Fp_tissue - Intercept_Fp) / Slope_Fp[27]

Calculate Redox Ratios:

- Determine the mitochondrial redox state using the concentration-based redox ratio [27]:

Fp Redox Ratio = [Fp]_tissue / ([Fp]_tissue + [NADH]_tissue)

- Determine the mitochondrial redox state using the concentration-based redox ratio [27]:

Workflow and Data Relationship Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data relationships for generating and applying the redox calibration curve.

Diagram: Redox Calibration and Quantification Workflow. This chart outlines the key stages of the protocol, from standard and sample preparation through scanning to final quantitative analysis.

The table below consolidates key quantitative information from the protocol for easy reference.

Table: Summary of Key Quantitative Parameters for Redox Calibration

| Parameter | Specification | Reference / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| NADH Linear Range | 165 μM to 1318 μM | Determined empirically using snap-frozen solution standards [27]. |

| FAD Linear Range | 90 μM to 720 μM | Determined empirically using snap-frozen solution standards [27]. |

| NADH Extinction Coefficient (ε) | 6,220 Mâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹ @ 360 nm | Used for verifying stock solution concentration [27]. |

| FAD Extinction Coefficient (ε) | 11,300 Mâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹ @ 450 nm | Used for verifying stock solution concentration [27]. |

| Scanning Temperature | 77 K (Liquid Nâ‚‚ temperature) | Provides ~10x fluorescence enhancement compared to room temperature [27]. |

| Typical Redox Ratio | Fp/(Fp + NADH) | A sensitive index of the mitochondrial redox state [27]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts for Redox Probe Selection

1. What are the primary functional differences between the ferro/ferricyanide couple and ruthenium complexes like [Ru(bpy)₃]²�

The ferro/ferricyanide couple ([Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») and tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) ([Ru(bpy)₃]²âº) are both fundamental redox probes, but they operate through distinct mechanisms, making them suitable for different applications.

- Ferro/ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â»): This is an inner-sphere redox probe. Its electron transfer rate is highly sensitive to the electrode surface state, cleanliness, and any surface modifications. It is excellent for characterizing surface properties and monitoring the successful formation of functional layers, as any change on the electrode will significantly affect its electron transfer kinetics. [1] [28]

- [Ru(bpy)₃]²âº: This is typically an outer-sphere redox probe. Its electron transfer is generally less sensitive to the specific chemistry of a well-prepared electrode surface and more predictable across different systems. It is often preferred for quantitative studies where a consistent and reliable redox signal is required, with less interference from surface conditions. [29] [1]

2. How does the choice of background electrolyte impact the performance of these redox probes?

The background electrolyte is not just a conductive medium; it actively interacts with the redox probes, significantly influencing the impedimetric or voltammetric signal. Key factors include ionic strength, pH, and buffer composition. [29]

- Ionic Strength: Increasing the ionic strength of the electrolyte (e.g., using a high concentration of KCl or PBS) compresses the electrical double layer. This can cause the semicircle in a Nyquist plot (from EIS) to shift to higher frequencies. Conversely, lower ionic strength shifts it to lower frequencies. [29]

- Buffer vs. Simple Salt: Using a buffered electrolyte like Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) often results in a lower standard deviation and reduced signal noise compared to a simple salt like KCl. This is crucial for achieving reproducible results, especially when using low-cost instrumentation. However, the buffer may slightly reduce overall sensitivity. [29]

- Redox Concentration Interaction: The concentration of the redox probe and the ionic strength of the electrolyte work in tandem. You can optimize the signal by using a high ionic strength buffer with a lower concentration of the redox probe to minimize noise and improve data quality. [29]

3. When should I expect to see shifts in formal potential or peak distortion, and what does it indicate?

Shifts in formal potential or distorted voltammetric peaks are not merely experimental errors; they are rich sources of information about your electrochemical interface. [1] [28]

- Shifts in Formal Potential: These often indicate specific interactions between the redox probe and the modified electrode surface. For instance, if your surface layer carries a net charge (positive or negative), it can attract or repel charged redox molecules, leading to a shift in the observed potential. [1]

- Peak Distortion or Weak Current: This frequently signals inhibited electron transfer. Common causes include:

- A contaminated or poorly prepared electrode surface.

- The successful formation of a dense, non-conductive Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) or a biorecognition layer (e.g., antibodies, DNA) that physically blocks the probe from reaching the electrode. [1] [28]

- A failed surface modification step, which would show minimal change in the redox signal before and after modification.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Redox Signal | Electrode surface contamination or fouling; Incorrect probe concentration; Instrument connection error. | Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) with a pristine electrode in a fresh standard solution (e.g., 1 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» in 0.1 M KCl). Check all cables and connections. | Re-polish and thoroughly clean the electrode (e.g., sequential sonication in solvent and water). Confirm redox probe is freshly prepared. |

| High Background Noise (Low S/N) | Low ionic strength; Unoptimized redox probe concentration; Electrical interference. | Run EIS in pure background electrolyte to establish baseline. Systematically increase ionic strength and observe signal stability. [29] | Switch from KCl to a buffered electrolyte like PBS. Use high ionic strength (>0.1 M) with lower redox probe concentration. [29] |

| Shift in Formal Potential (Eâ°) | Charged functional layers on electrode surface; Change in pH or solution composition. | Compare CVs before and after surface modification. Measure solution pH. | If the shift is consistent and reproducible after modification, it may confirm successful layer formation. Ensure pH is controlled with a buffer. |

| Broken or Inconsistent RC Semicircle in EIS | Unoptimized overlap of RC time constants from electrolyte and redox species. [29] | Run EIS scans with varying concentrations of redox probe and ionic strength. [29] | Adjust the ratio of redox probe concentration to electrolyte ionic strength to separate the semicircles clearly. [29] |

| Signal Drift Over Time | Degradation of redox probe in solution; Enzyme degradation (for enzyme-based sensors); Reference electrode potential drift. [11] | Test with a freshly prepared solution. Check sensor calibration against standard. | Use freshly prepared redox solutions. For implantable/long-term sensors, implement a self-calibration protocol if possible. [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Electrolyte and Redox Probe Concentration for EIS

This protocol is designed to find the ideal combination of redox probe and electrolyte for a sensitive and stable impedimetric signal, particularly when using cost-effective analyzers. [29]

1. Materials and Reagents

- Redox Probes: 10 mM stock solutions of potassium ferricyanide(III)/potassium ferrocyanide(II) (1:1 mixture) and Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) chloride ([Ru(bpy)₃]²âº).

- Electrolytes: 1 M Potassium Chloride (KCl) and 1X Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Electrochemical workstation or impedance analyzer (e.g., Keysight 4294A or Analog Discovery 2).

2. Experimental Procedure

- Step 1: Prepare Solutions. Create a matrix of solutions by diluting the redox stock solutions into the electrolytes. A suggested starting point is to test redox concentrations of 0.1 mM, 1 mM, and 5 mM in both 0.1 M KCl and 0.1 M PBS.

- Step 2: Run Impedance Spectroscopy. For each solution, perform EIS over a suitable frequency range (e.g., 100 Hz to 1 MHz) with a small amplitude AC voltage (~10 mV). Record the Nyquist plots.

- Step 3: Analyze Data. Observe how the characteristic semicircle (representing the charge transfer resistance, Rₑₜ) changes.

- Note how the semicircle's position on the frequency axis shifts with changing ionic strength and redox concentration. [29]

- Calculate the standard deviation of replicates to determine which condition provides the most stable signal.

3. Expected Outcome and Decision

- Optimal Signal: The condition that produces a well-defined semicircle with the lowest standard deviation is typically optimal. The study found that PBS with high ionic strength and a lowered redox probe concentration often achieves this, making the signal more robust for low-cost analyzers. [29]

Protocol 2: Validating Electrode Surface Modification Using Cyclic Voltammetry

Use this protocol at each stage of biosensor fabrication to confirm successful surface modification. [1]

1. Baseline Measurement

- Prepare a standard solution of 1 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» in 0.1 M PBS.

- Using a clean, bare electrode, run a cyclic voltammogram (e.g., from -0.1 V to +0.5 V vs. Ag/AgRef, scan rate 50 mV/s). Record the peak potentials and peak-to-peak separation (ΔEₚ).

2. Post-Modification Measurement

- After modifying the electrode (e.g., with a SAM, aptamer, or antibody), rinse it gently.

- Run a CV in the same standard solution used in Step 1.

- Compare the new voltammogram to the baseline.

3. Interpretation of Results

- Successful Blocking: A significant decrease in peak current and an increase in ΔEₚ indicate that the functional layer has been successfully attached and is hindering electron transfer to the redox probe. [1]

- Failed Modification: Little to no change in the CV suggests the modification was unsuccessful.

- Surface Contamination: A distorted, poorly shaped wavefront indicates a dirty or poorly prepared surface.

Signaling Pathways and Optimization Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and optimizing redox probes based on experimental goals and observed outcomes.

Redox Probe Selection and Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials and their functions for experiments involving these redox probes.

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Ferro/Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») | Inner-sphere redox probe; highly sensitive to surface chemistry, ideal for validating surface modifications and cleaning. [1] | Typically used as a 1:1 mixture, 1-5 mM in 0.1 M KCl or PBS. [29] |

| Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) ([Ru(bpy)₃]²âº) | Outer-sphere redox probe; provides a more consistent and reliable signal, less sensitive to surface chemistry. [29] [1] | ~1 mM concentration in buffered solutions. [29] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Buffered electrolyte; maintains stable pH, reduces signal noise and standard deviation compared to simple salts. [29] | 0.1 M concentration, pH 7.4. [29] |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Simple salt electrolyte; provides high ionic strength but may lead to higher signal variance. [29] | 0.1 M concentration or higher. [29] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, reproducible working electrodes; ideal for rapid testing and POC device development. [29] | Carbon, gold, or platinum working electrodes. |

| Analog Discovery 2 | Low-cost USB oscilloscope/impedance analyzer; enables transition to affordable POC devices. [29] | ~$200 cost, capable of sensitive EIS measurements when electrolyte is optimized. [29] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my biosensor's calibration curve show a non-monotonic response (current decreases then increases) at high substrate concentrations instead of the expected saturation plateau?

A1: This behavior is a classic signature of uncompetitive or mixed substrate inhibition coupled with external diffusion limitations [30]. At high substrate levels (S > KI, where KI is the inhibition constant), the substrate itself acts as an inhibitor, binding to the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) to form an inactive complex (ESS). When this reaction occurs within a thin enzyme layer where substrate transport is diffusion-limited, it can produce a transient local minimum in the current response before reaching a steady state [30]. You should:

- Verify Kinetic Constants: Determine your enzyme's inhibition constants (KI, KI') experimentally.

- Inspect Transient Data: Analyze the full time-course of your response, not just the steady state. A five-phase pattern (zero → global maximum → local minimum → increase → steady state) confirms this phenomenon [30].

- Adjust Enzyme Layer: Reduce the thickness of your enzyme membrane to minimize internal diffusion resistance, which can amplify this effect.

Q2: How can I accurately model my biosensor's response when the calibration data does not fit classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics?

A2: You need to extend your model to include non-Michaelis-Menten kinetics and a multi-layer (compartment) structure. The reaction rate equation must account for inhibition. For instance, for uncompetitive inhibition, the rate V(S) is given by [30]:

V(S) = V_max * S / [K_M + S + (S^2 / K_I)]

Your reaction-diffusion model should consist of at least two compartments:

- An enzyme layer where both reaction and diffusion occur.

- An outer diffusion layer where only diffusion takes place. Using a finite difference method to numerically solve this system of partial differential equations will provide a more accurate fit to your calibration data [30].

Q3: What are the best computational methods to simulate a calibration curve based on a complex reaction-diffusion-inhibition model?

A3: The choice depends on your goal:

- For High Accuracy in Complex Geometries: Use numerical methods like the finite difference method (FDM) to solve the coupled non-linear partial differential equations. This is robust for intricate models involving multiple layers and inhibition [30].

- For Rapid Parameter Estimation & Sensitivity Analysis: Employ machine learning techniques. Specifically, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (LMT) can efficiently map model parameters to sensor output, allowing you to quickly explore the effect of parameter variations on your calibration curve [31] [32]. The initial training data for the ANN is often generated using a traditional numerical solver like MATLAB's

pdex4[32].

Q4: How does external diffusion limitation specifically affect the calibration of a biosensor operating under substrate inhibition?

A4: External diffusion limitation exacerbates the effects of inhibition and can lead to calibration inaccuracies if not properly accounted for. It causes the substrate concentration within the enzyme layer (S_internal) to be significantly lower than in the bulk solution (S_bulk). Since inhibition is a nonlinear function of concentration, this difference distorts the sensor's response. The system's behavior is governed by the relative rates of reaction and diffusion, often summarized by the Thiele modulus (σ²). A high Thiele modulus means reaction is fast compared to diffusion, leading to steeper concentration gradients and a more pronounced deviation from ideal kinetic behavior [33]. In practice, this means that a calibration model based solely on bulk concentration and reaction kinetics will overestimate the current output.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Non-Ideal Calibration Curves

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-monotonic transient response (current peaks, then dips) [30] | Uncompetitive/mixed substrate inhibition with external diffusion limitation. | 1. Plot full current-time trajectory.2. Check if S_bulk > K_M and S_bulk > K_I.3. Vary stirring speed; if response changes, diffusion is a factor. |

Incorporate the correct inhibition mechanism into your calibration model. Use a two-compartment reaction-diffusion model for simulation. |

| Lower sensitivity than predicted by model without inhibition [30] [33] | Competitive inhibition or signal loss from enzyme degradation. | 1. Add inhibitor to solution; if response drops further, competitive inhibition is likely.2. Test biosensor with fresh standard solutions to rule out enzyme aging. | For inhibition: Use a competitive inhibition model (V = V_max * S / [K_M*(1+S/K_I') + S]). For degradation: Implement a self-calibration protocol [11]. |

| Poor fit of steady-state model to transient data | Model ignores external diffusion layer. | Compare model that includes an outer diffusion layer to one that does not. | Use a two-compartment model that includes the thickness (d2) and diffusion coefficient of the outer diffusion layer [30]. |

| High signal noise in wearable biosensor in vivo [11] | Biofouling, enzyme degradation, or tissue variation. | Perform a recalibration against a reference method (e.g., blood test). | Design a self-calibrating system. This can involve a microneedle array that delivers a standard solution in situ to recalibrate the sensor [11]. |