Engineering Electron Transfer in Proteins: Strategies for Enhanced Biocatalysis and Biomedical Applications

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in protein engineering for enhancing electron transfer efficiency, a critical bottleneck in biocatalysis and bioelectrochemical systems.

Engineering Electron Transfer in Proteins: Strategies for Enhanced Biocatalysis and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in protein engineering for enhancing electron transfer efficiency, a critical bottleneck in biocatalysis and bioelectrochemical systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores foundational principles of biological electron transport, cutting-edge engineering methodologies from rational design to AI-driven approaches, and strategies for troubleshooting common challenges. By validating these techniques through comparative analysis of successful applications in natural product synthesis, biofuel cells, and microbial systems, this review provides a comprehensive framework for designing high-performance engineered proteins to drive innovation in biomanufacturing, biosensing, and therapeutic development.

The Principles and Challenges of Biological Electron Transfer

FAQs: Electron Transfer Fundamentals

1. What is an Electron Transport Chain (ETC) and what is its primary function? An Electron Transport Chain is a series of protein complexes and other molecules embedded within a membrane that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions. The primary function of an ETC is to couple the energy released from these exergonic electron transfers with the endergonic pumping of protons across a membrane. This creates an electrochemical gradient, or proton motive force, that drives the synthesis of ATP and other cellular processes [1] [2].

2. In eukaryotic cells, where are the primary ETCs located? In eukaryotic cells, the primary ETC for cellular respiration is found on the inner mitochondrial membrane. For photosynthesis in photosynthetic eukaryotes, the ETC is located on the thylakoid membrane within chloroplasts [3] [1].

3. What are the main entry points for electrons into the mitochondrial ETC? Electrons primarily enter the mitochondrial ETC through two complexes:

- Complex I (NADH Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase): Accepts electrons from NADH.

- Complex II (Succinate Dehydrogenase): Accepts electrons from succinate (via FADH2) in the citric acid cycle. Other enzymes, like Glycerol-3-Phosphate dehydrogenase and Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, also funnel electrons into the quinone pool via FADH2 [3] [1].

4. What is the terminal electron acceptor in aerobic respiration? In aerobic respiration, molecular oxygen (Oâ‚‚) is the final electron acceptor. At Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), four electrons, four protons, and one Oâ‚‚ molecule combine to form two molecules of water [3] [1].

5. How is the electron transport chain coupled to ATP production? The energy from electron transfer is used to pump protons (Hâº) across the inner mitochondrial membrane, creating a proton gradient. This gradient increases the acidity in the intermembrane space and creates an electrical potential. The enzyme ATP synthase (sometimes called Complex V) uses the energy from the flow of protons back down this gradient into the matrix to phosphorylate ADP, forming ATP. This overall process is known as oxidative phosphorylation [3] [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Low Catalytic Efficiency in Engineered P450 Systems

Problem: Engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes show low product yield, often due to inefficient electron transfer from redox partners (RPs), leading to slow catalysis and uncoupling events [4].

Potential Solutions:

- Create Fusion Constructs: Genetically fuse the P450 enzyme to its redox partner to optimize proximity and orientation. This enhances the electron transfer rate and improves coupling efficiency [4].

- Engineer the Interaction Interface: Use site-directed mutagenesis to modify amino acids at the P450-RP interaction interface. This can strengthen binding and optimize the electron transfer pathway [4].

- Utilize Scaffold-Mediated Assembly: Assemble P450s and RPs on synthetic protein scaffolds. This allows for precise control over the stoichiometry and spatial organization of the components, mimicking natural multi-enzyme complexes [4].

Issue 2: Excessive Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Formation

Problem: Electron leakage from the ETC, particularly from Complex I and III, leads to the premature reduction of oxygen, forming superoxide and other ROS. This can cause cellular damage or, in engineered systems, lead to unproductive side reactions [1] [5].

Potential Solutions:

- Optimize Electron Flow: In engineered systems, ensure efficient electron delivery to the catalytic center. Strategies from Problem 1 (fusion constructs, interface engineering) can reduce electron leakage by providing a more direct path to the intended acceptor [4].

- Inhibit Specific ETC Complexes: In research settings, use specific ETC inhibitors to study and manipulate electron flow.

- Monitor Metabolic Shifts: As seen in chronic lymphocytic leukemia studies, CD40 signaling upregulates oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and confers drug resistance. Inhibiting the ETC at Complex I, III, or V can counteract such resistance mechanisms linked to altered cellular metabolism [5].

Issue 3: Poor Electron Transfer from Non-Native Donors

Problem: When designing novel biohybrid systems (e.g., coupling inorganic light harvesters to enzymes), electron transfer from the non-native donor to the biological component is inefficient [6].

Potential Solutions:

- Understand the Electron Donor: Characterize the reduction potential and electron delivery kinetics of the non-native donor (e.g., a nanocrystal) to identify compatibility with the enzyme's natural electron acceptor [6].

- Engineer the Enzyme's Electron Entry Point: Modify the enzyme's surface around its native electron acceptor cofactor (e.g., an iron-sulfur cluster) to improve binding and electron transfer from the synthetic donor [6].

- Investigate Electron Spin: Be aware that electron spin can play a critical role in the efficiency of biological electron transfer and catalysis. Modifying the protein environment can tune the spin state of metal cofactors to facilitate electron flow [6].

Quantitative Data on Mitochondrial Electron Transfer

Table 1: Proton Translocation and ATP Yield in the Mitochondrial ETC

| ETC Complex | Electron Input | Primary Function | Protons Pumped per 2 eâ» | ~ATP Yield (per Electron Pair) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I | NADH | Oxidizes NADH, reduces CoQ | 4 H⺠[3] | 2.5 ATP [3] |

| Complex II | FADH₂ (from succinate) | Oxidizes succinate, reduces CoQ | 0 H⺠[3] | 1.5 ATP [3] |

| Complex III | QH₂ (via Q-cycle) | Oxidizes QH₂, reduces Cyt c | 4 H⺠(per full Q-cycle) [3] | — |

| Complex IV | Reduced Cyt c | Reduces O₂ to H₂O | 2 H⺠[3] | — |

| ATP Synthase | — | Uses H⺠gradient to make ATP | — | Consumes ~4 H⺠per ATP [3] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ETC Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Target | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Oligomycin | Inhibits ATP synthase (Complex V) [5] | Blocks proton flow through ATP synthase, allowing measurement of the proton gradient's contribution to cellular processes [5]. |

| Antimycin A | Inhibits Complex III [1] | Used to study the Q-cycle and induces electron leakage for ROS generation studies [1]. |

| Cyanide (CNâ») | Inhibits Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) [1] | Halts electron transfer at the final step, preventing oxygen consumption and causing a full collapse of the proton gradient. |

| 2-Deoxy-D-glucose | Glycolysis inhibitor [5] | Distinguishes the contributions of glycolysis and OXPHOS to overall cellular ATP production and survival [5]. |

| 6-diazo-5-oxo-L-norleucine (DON) | Inhibits glutaminolysis [5] | Used to investigate the role of glutamine in fueling the TCA cycle and, consequently, mitochondrial OXPHOS [5]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Electron Transfer Efficiency via Oxygen Consumption

Principle: The rate of oxygen consumption is a direct indicator of ETC activity, as oxygen is the terminal electron acceptor in aerobic respiration.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Isolate mitochondria from tissue or use intact cells in a suitable buffer. For engineered protein systems, reconstitute the proteins in liposomes or nanodiscs that mimic the native membrane environment.

- Substrate Addition: Introduce specific electron donors:

- For Complex I-driven respiration, add glutamate/malate or pyruvate/malate.

- For Complex II-driven respiration, add succinate (often in the presence of a Complex I inhibitor like rotenone).

- Inhibition Assay: Sequentially add specific ETC inhibitors (see Table 2) to dissect the contribution of each complex to the total respiratory capacity.

- Data Analysis: Calculate basal respiration, ATP-linked respiration, and proton leak based on the response to inhibitors. A sharp drop in oxygen consumption rate after adding an inhibitor confirms the activity of the targeted complex [5].

Protocol 2: Engineering a P450-Redox Partner Fusion Protein

Principle: Enhancing the proximity and optimal orientation between a cytochrome P450 and its redox partner can drastically improve electron transfer efficiency and reduce uncoupling.

Methodology:

- Construct Design:

- Use a flexible peptide linker (e.g., Gly-Ser repeats) to genetically fuse the C-terminus of the P450 to the N-terminus of its redox partner (e.g., cytochrome P450 reductase), or vice versa. The linker length should be optimized to allow proper folding and interaction.

- Alternatively, use rigid linkers or protein-protein interaction domains for a fixed orientation.

- Expression and Purification: Clone the fusion gene into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET series for E. coli). Express the recombinant protein and purify it using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification).

- Functional Characterization:

- Coupling Efficiency: Measure the ratio of product formed to NADPH consumed. A higher ratio indicates less electron leakage and better coupling.

- Catalytic Activity (kcat/Km): Determine the enzyme's turnover number and substrate affinity. Compare these values between the fused and non-fused systems to quantify the improvement [4].

- ROS Detection: Use fluorescent probes like dichlorofluorescein or Amplex Red to detect and quantify hydrogen peroxide formation, a key uncoupling product [4].

Electron Transfer Pathway Visualizations

Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain

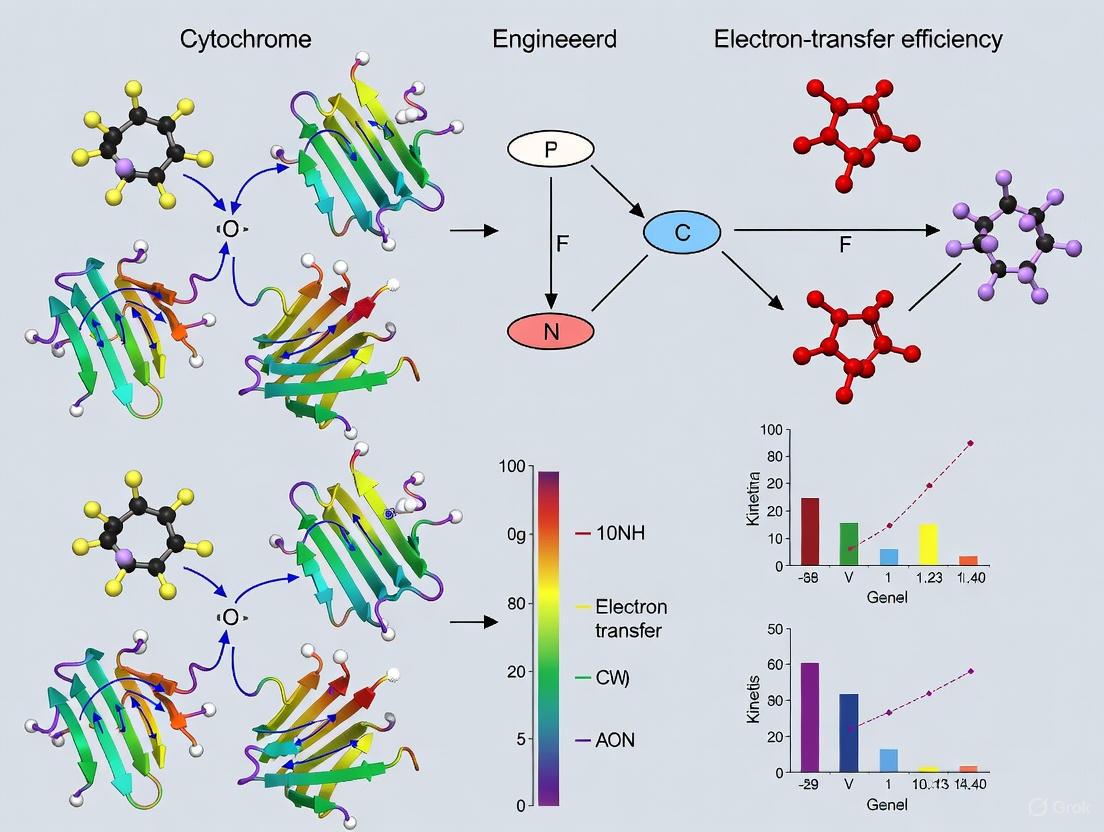

P450 Electron Transfer Engineering Workflow

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Engineered Protein Research. A critical bottleneck in utilizing biocatalysts like Cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450s) is the inefficient electron transfer process, which often limits catalytic efficiency and promotes uncoupling events [4]. These uncoupling reactions lead to the wasteful consumption of expensive NAD(P)H cofactors and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) like superoxide anion (•O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [4] [7]. ROS accumulation causes oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA, and can inactivate both the enzyme and the host organism [8] [7]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you overcome these challenges, enhance coupling efficiency, and develop robust systems for your research and development projects.

FAQ: Understanding Core Concepts

Q1: What is "coupling efficiency" in P450 catalysis, and why is it critical?

A: Coupling efficiency is the percentage of electrons from the cofactor NAD(P)H that are used for the intended substrate conversion versus those that are "wasted" or "uncoupled," leading to the reduction of oxygen and the formation of reactive oxygen species like superoxide and hydrogen peroxide [7]. High coupling efficiency is critical because uncoupling results in:

- Extra consumption of expensive NAD(P)H cofactor [7].

- Accumulation of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [4] [7].

- Oxidative damage to cellular components (DNA, proteins, lipids) and potential enzyme inactivation [8] [7].

- Reduced overall catalytic efficiency and product yield [4].

Q2: What are the primary molecular factors that contribute to uncoupling in P450s?

A: Uncoupling can be attributed to inefficiencies in three main areas [7]:

- Substrate Binding Pocket: A suboptimal substrate binding pocket (e.g., poor substrate positioning, low binding affinity) can hinder the efficient transfer of an oxygen atom to the substrate.

- Ligand Access Tunnels: Inefficient channels for substrate entry or product exit can slow down the catalytic cycle, increasing the chance for electron leakage to oxygen.

- Electron Transfer Pathway(s): The rate of electron delivery from redox partners (RPs) to the P450's heme center can be a limiting step. A slow electron transfer rate relative to other steps in the cycle creates opportunities for uncoupling [4] [7].

Q3: What is the chemical relationship between different Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)?

A: ROS form a network of interconnected species. The primary ROS, the superoxide anion (•O2−), is produced by the one-electron reduction of molecular oxygen [8]. It is a precursor to most other ROS. Superoxide can be dismutated (by Superoxide Dismutase, SOD) to form hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [9]. H2O2, while not highly reactive on its own, can be converted in the presence of ferrous or cuprous ions via the Fenton reaction into the extremely reactive and damaging hydroxyl radical (•OH) [8] [9]. It is crucial to understand that "ROS" is a generic term, and the specific species involved has major implications for its reactivity, lifespan, and the damage it causes [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Electron Transfer and Coupling Efficiency

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Product Yield & High Cofactor Consumption | High uncoupling due to inefficient electron transfer or poor substrate binding. | • Engineer fusion constructs between P450 and redox partner.• Apply directed evolution to optimize the P450-RP interaction interface.• Use semi-rational design to optimize substrate binding pocket. | [4] [7] |

| Enzyme Inactivation & Cellular Toxicity | Accumulation of ROS (e.g., H2O2, •OH) from uncoupled reactions causing oxidative stress. | • Improve coupling efficiency to reduce ROS at the source.• Co-express antioxidant enzymes (e.g., Catalase, SOD).• For in vitro systems, add stoichiometric ROS scavengers (with caution). | [4] [8] [7] |

| Slow Catalytic Rate | Rate-limiting electron transfer from redox partners (e.g., ferredoxins). | • Engineer ferredoxins for enhanced electron donation.• Utilize scaffold-mediated protein assembly for optimal spatial organization.• Employ protein engineering to fine-tune redox potentials. | [4] [10] |

| Difficulty Measuring Specific ROS | Use of non-specific probes or assays; treating "ROS" as a single entity. | • Use selective generators/inhibitors (see Table 3).• Measure specific oxidative damage biomarkers (e.g., lipid peroxides, 8-OHdG).• Avoid reliance on commercial "ROS" kits without mechanistic validation. | [9] |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing Electron Transfer via Fusion Constructs

Aim: To improve catalytic efficiency and coupling by genetically fusing a Cytochrome P450 with its redox partner to minimize electron transfer distance.

Materials:

- Plasmid DNA encoding your P450 enzyme and its native redox partner (e.g., a ferredoxin).

- PCR reagents (High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, dNTPs).

- Appropriate restriction enzymes and ligase or a seamless cloning kit.

- Linker sequences (e.g., (GGGGS)(_n) for flexibility).

- Expression host (e.g., E. coli Rosetta (DE3)).

- Chromatography system for protein purification (e.g., Ni-NTA if using His-tag) [11].

Method:

- In Silico Design: Model the fusion protein structure to determine the optimal fusion site (N- or C-terminus) and linker length that connects the P450 and redox partner without disrupting active sites. Tools like AlphaFold 3 can be highly beneficial for this [4].

- Plasmid Construction:

- Expression and Purification:

- Transform the constructed plasmid into your expression host.

- Induce protein expression with IPTG.

- Lyse cells and purify the fusion protein using affinity chromatography [11].

- Characterization:

- Catalytic Activity: Measure substrate consumption and product formation using HPLC or GC-MS.

- Coupling Efficiency: Calculate by comparing the moles of product formed to the moles of NAD(P)H consumed.

- ROS Detection: Use specific assays (e.g., Amplex Red for H(2)O(2)) to quantify ROS production by the fused versus unfixed enzyme system [9].

This workflow for constructing and characterizing a fusion enzyme is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Electron Transfer and ROS Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ferredoxin (Fd) Engineering [10] | Serves as a tunable redox partner for transferring electrons to P450s. | Can be engineered (fission, fusion, domain insertion) to regulate electron transfer based on external stimuli like protein-protein interactions. |

| Gold-Binding Peptides (GBP) [11] | Fused to enzymes to control their orientation on electrode surfaces for enhanced Direct Electron Transfer (DET). | Improves efficiency of bioelectrocatalytic systems like biosensors and biofuel cells. |

| d-Amino Acid Oxidase (DAAO) [9] | A genetically encodable tool for controlled, localized generation of H2O2 in vivo. | Allows precise regulation of H2O2 flux by varying d-alanine concentration; used to study redox signaling and damage. |

| MitoPQ [9] | A targeted compound that generates superoxide (•O2(^-)) specifically within mitochondria. | Useful for studying site-specific effects of superoxide and mitochondrial oxidative stress. |

| Paraquat (PQ) [9] | A redox-cycling compound that generates superoxide (•O2(^-)) in the cytosol. | A common tool to induce general oxidative stress; effects are not site-specific. |

| N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) [9] | A widely used "antioxidant" with multiple modes of action. | Does not directly scavenge H2O2 effectively. Effects may be due to increasing cellular glutathione levels or other mechanisms. Use with caution when interpreting results. |

| Gyrophoric acid | Gyrophoric Acid|High-Purity Lichen Metabolite | |

| Oxypertine | Oxypertine, CAS:153-87-7, MF:C23H29N3O2, MW:379.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Table 3: Reagents for Modulating and Measuring ROS

| Reagent / Method | Target ROS | Principle & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) [9] | Superoxide (•O2(^-)) | Enzymatic scavenger. Used to confirm the involvement of superoxide. |

| Catalase [9] | Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) | Enzymatic decomposition to H2O and O2. Confirms H2O2 involvement. |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR/ESR) [9] | Radical species (e.g., •OH, •O2(^-)) | The gold-standard for direct detection and identification of radical species. |

| Biomarker Analysis [9] | N/A (Measures damage) | Quantifies specific oxidative damage products (e.g., 8-OHdG for DNA, lipid hydroperoxides for lipids). Provides a footprint of ROS activity. |

Advanced Engineering Strategies

To systematically overcome bottlenecks, a multi-faceted engineering approach is required. The following diagram illustrates the interconnected strategies targeting the key areas of the enzyme.

Future Directions: The field is moving towards integrating advanced computational modeling (like AlphaFold 3 [4]) with high-throughput directed evolution and systems biology. This combined approach allows for the predictive design of efficient, coupled, and robust P450 systems for industrial applications, from drug manufacturing to biofuel production [4] [7].

Core Concepts FAQ

What are aromatic residue networks and why are they important in electron transfer (ET)? Aromatic residue networks are chains of tryptophan (Trp) or tyrosine (Tyr) residues within a protein structure that facilitate the movement of electrons (or electron holes) over long distances. They are crucial because they enable key biological processes, including photosynthesis and enzyme catalysis, by acting as redox-active intermediaries. These networks can transfer oxidizing equivalents away from sensitive active sites toward the protein surface, thereby playing a protective role against damage [12]. Approximately one-third of all proteins contain such chains of more than three Trp or Tyr residues [12].

What is the fundamental mechanism behind electron transfer through these residues? Electron transfer often occurs via a hole-hopping mechanism, where an electron hole (a positive charge) moves through the aromatic network [13]. This process is frequently a Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer (PCET), where the movement of an electron is coupled with the transfer of a proton [14]. The aromatic side chains of Trp and Tyr are excellent at this because their resonant π-systems can stabilize radical intermediates during the transfer process [15].

How do the properties of tryptophan and tyrosine compare in PCET? While both are crucial, their thermodynamic properties differ. The redox potential of a residue defines its tendency to gain or lose an electron, and its pKâ‚ value influences proton transfer. These properties can be tuned by the protein environment. Furthermore, fluorinated analogs of these amino acids have been developed to probe PCET mechanisms, as the addition of fluorine atoms systematically alters their redox potential and pKâ‚ [13].

Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Issue 1: Low Electron Transfer Efficiency in Engineered Protein

- Problem: Your designed protein shows inefficient electron conduction despite the presence of aromatic residues.

- Solutions:

- Check Residue Spacing and Orientation: Efficient ET requires precise orientation and distance between aromatic residues. Use computational modeling to ensure optimal orbital overlap for superexchange or hopping [16]. Replacing phenylalanine with tryptophan at critical positions can enhance electronic coupling between cofactors [16].

- Optimize the Redox Potential Gradient: ET is driven by a favorable redox potential (Em) cascade. Calculate the Em values of Trp residues in your structure. A chain of tryptophans with a descending Em gradient facilitates directional hole hopping [12].

- Introduce Polar Residues: In some systems, pairing tryptophan with a polar residue like threonine can markedly improve ET yield, potentially by influencing cofactor binding or redox potential [16].

Issue 2: Unstable Radical Intermediates During Turnover

- Problem: Your enzyme system accumulates damaging radicals, leading to inactivation.

- Solutions:

- Design a Protective Hole-Hopping Pathway: Integrate a chain of Trp/Tyr residues to safely divert holes away from the active site. In cytochrome P450 enzymes, such chains prevent damage from high-potential intermediates by transferring the oxidizing equivalent to a less sensitive site [17]. A common structural motif in eukaryotic P450s is a tryptophan hydrogen-bonded to the heme D-propionate, which extends the enzyme's lifetime during turnover [17].

- Engineer the Microenvironment: The local electrostatic environment significantly stabilizes charged radical states. Introducing acidic residues near the catalytic pocket can facilitate deprotonation steps, accelerating PCET and stabilizing the radical [15].

Issue 3: Difficulty in Probing PCET Mechanisms Experimentally

- Problem: Challenges in directly observing the role of specific Trp/Tyr residues in a complex PCET pathway.

- Solutions:

- Use Unnatural Amino Acids (UAAs): Incorporate mono-fluorotryptophans via genetic code expansion. Fluorination tunes the redox potential and pKâ‚ of the indole side chain, allowing you to map the kinetics and thermodynamics of the PCET pathway [13]. The table below summarizes the properties of these probes.

- Employ Advanced QM/MM Simulations: Utilize computational protocols like DFTB3/MM metadynamics to generate free energy surfaces for PCET reactions. This helps understand how donor-acceptor orientation and environmental dynamics influence the mechanism [14].

Table 1: Fluorotryptophan Probes for Mechanistic Studies

| Probe Name | Impact on Properties | Primary Application in PCET Studies |

|---|---|---|

| 4-fluoro-Trp | Alters indole electronics at C4 position [13] | Tuning redox potential to test hole-hopping rates. |

| 5-fluoro-Trp | Alters indole electronics at C5 position [13] | Probing electronic coupling in the pathway. |

| 6-fluoro-Trp | Alters indole electronics at C6 position [13] | Mapping the thermodynamic landscape of ET. |

| 7-fluoro-Trp | Alters indole electronics at C7 position [13] | Investigating the role of protonation states. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Analysis of Aromatic Networks

This protocol is used to identify and evaluate potential ET pathways in a protein of known structure [12] [14].

- Structure Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution crystal or cryo-EM structure (PDB format). Add hydrogens and assign protonation states using standard molecular modeling software.

- Identify Aromatic Clusters: Map all Trp, Tyr, and Phe residues in the structure. Identify clusters where aromatic side chains are within 5-7 Ã… (van der Waals contact).

- Calculate Redox Potentials (Em): Solve the linear Poisson-Boltzmann equation for the entire protein, considering the equilibrium with all titratable sites. This calculates the Em(Trp/Trp•+) or Em(Tyr/Tyr•) for each residue in the network [12].

- Model Electron Hole Hopping: Use Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical (QM/MM) calculations on the entire protein environment to model the kinetics and energetics of hole transfer through the identified pathway [12].

- Analysis: A pathway is considered feasible if it shows a cascade of redox potentials and QM/MM calculations confirm low energy barriers for hole hopping.

Protocol 2: Engineering an Enhanced ET Pathway in a Bacterial Reaction Center

This protocol summarizes the successful redesign of a vestigial ET pathway [16].

- Parent System Selection: Start with a reaction center variant where ET to the native A-branch is disabled and ET is redirected to the B-branch (e.g., the "YEFHV" RC from C. sphaeroides).

- Scan with Tryptophans: Systematically introduce Trp residues at positions between the HB bacteriopheophytin and QB quinone cofactors on the B-branch. Replace existing non-aromatic or phenylalanine residues.

- Combinatorial Mutagenesis: Combine beneficial Trp mutations with polar substitutions (e.g., threonine) that can improve quinone binding or modulate its redox potential.

- Characterize ET Yield: Measure the yield of the secondary electron transfer step (P+HB– → P+QB–) using transient absorption spectroscopy. The goal is to achieve a yield approaching ~95%, as demonstrated in successful variants [16].

- Validate with Overall Charge Separation: Confirm that the engineered pathway leads to a dramatic enhancement of stable transmembrane charge separation.

Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Aromatic Network Engineering Workflow.

Diagram 2: Directional Hole Hopping via a Tryptophan Redox Cascade.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Studying Aromatic ET Networks

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorinated Tryptophan Analogs (4-F, 5-F, 6-F, 7-F-Trp) | Chemically tune redox potential and pKâ‚ to probe PCET mechanisms; incorporate via genetic code expansion [13]. | Requires an orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase/tRNA pair for site-specific incorporation. |

| QM/MM Simulation Software (e.g., DFTB3/MM) | Models PCET reactions with atomic detail, generating free energy surfaces at a lower computational cost than full DFT [14]. | Protocol requires careful selection of collective variables (CVs) for proton and electron transfer. |

| Biomimetic Peptide Systems (e.g., β-hairpin, α-helical maquettes) | Simplified, well-defined models to study PCET mechanisms in a controlled environment, isolating specific variables [14]. | Allows systematic testing of factors like residue orientation, solvation, and electrostatic effects. |

| Metadynamics Sampling | An enhanced sampling computational method to overcome energy barriers and efficiently explore PCET reaction pathways [14]. | Crucial for achieving sufficient sampling of rare events like proton transfers on nanosecond timescales. |

| D-(+)-Fucose | D-(+)-Fucose, CAS:3615-41-6, MF:C6H12O5, MW:164.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SC-VC-Pab-mmae | SC-VC-Pab-mmae, MF:C68H105N11O17, MW:1348.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs: Core Principles and Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: What are the primary redox cofactors in the mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC), and what are their key functions? The mitochondrial ETC relies on three primary classes of redox cofactors: flavins, iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters, and hemes. Each has a distinct role and location [18] [1]:

- Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN): Found in Complex I, FMN acts as the primary electron acceptor from NADH. It can transfer electrons one at a time or in pairs, feeding them into a chain of Fe-S clusters [1] [19].

- Iron-Sulfur (Fe-S) Clusters: These are inorganic cofactors ([2Fe-2S], [3Fe-4S], [4Fe-4S]) that transfer single electrons. They are abundant in Complexes I, II, and III, where they function as an "electron wire" due to the delocalization of electrons over both iron and sulfur ions [18] [20]. For instance, Complex I contains up to ten Fe-S clusters, and Complex II uses three to transfer electrons from FADH2 to ubiquinone [20].

- Hemes: These are iron-containing porphyrin cofactors. Different types (hemes b, c, and a) are found across Complexes II, III, and IV. Their protein environment finely tunes their reduction potential. In Complex IV, a unique heme a₃ pairs with a copper ion (CuB) to form the binuclear center where molecular oxygen is reduced to water [21] [18] [1].

Q2: In engineered proteins, what are the primary factors limiting efficient electron transfer (ET) to electrodes? The main challenges in achieving efficient Direct Electron Transfer (DET) for bioelectrochemical devices are [22]:

- Buried Active Sites: The electroactive cofactors (flavin, heme, Fe-S clusters) are often deeply embedded within an insulating protein matrix, creating a physical barrier for electron exchange with an electrode [22].

- Distance: According to Marcus theory, the efficiency of electron transfer decreases exponentially with distance. The theoretical maximum for efficient electron tunneling via quantum mechanics is approximately 20 Ã…. Achieving DET beyond this range requires a chain of cofactors to "wire" the internal site to the protein surface [22].

- Protein Orientation: Non-specific immobilization on an electrode surface leads to a mixed population of enzyme orientations. Only a fraction of the molecules will be optimally positioned for efficient electron transfer to the electrode [22].

Q3: How can protein engineering overcome inefficient electron transfer in engineered systems? Several protein engineering strategies can enhance ET efficiency [22]:

- Protein Truncation: Deleting non-essential protein domains or subunits can expose buried redox cofactors, reducing the electron tunneling distance to the electrode surface. For example, truncating the heme subunit of fructose dehydrogenase improved DET efficiency by downsizing the enzyme's footprint and improving orientation [22].

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introducing point mutations can fine-tune the redox properties of cofactors or create new binding sites for covalent attachment to electrodes. Studies in photosystem I have shown that single amino acid substitutions in the phylloquinone-binding pocket can alter electron transfer kinetics by orders of magnitude [23].

- Fusion Tags: Genetically fusing an electron-transferring domain (like a multi-heme cytochrome) to a non-DET enzyme can provide a dedicated pathway for electrons to shuttle from the active site to the electrode. A flexible peptide linker is crucial to maintain accessibility [22].

Q4: Why might my experimental system show low activity after incorporating a redox cofactor, and how can I troubleshoot this? Low activity can stem from improper cofactor incorporation or instability.

- Cause 1: Incomplete Cofactor Biosynthesis and Insertion. Heme and Fe-S clusters require complex biosynthetic machinery. In mammalian cells, the absence of heme can prevent the proper folding and assembly of entire complexes, such as Complex IV [21]. Fe-S cluster stability is highly sensitive to oxygen, which can cause cluster disassembly and protein inactivation [20].

- Troubleshooting:

- Validate successful cofactor incorporation using UV-Vis spectroscopy to confirm the characteristic absorption peaks of hemes (e.g., Soret band) or Fe-S clusters.

- For Fe-S cluster-dependent proteins, perform experiments under anaerobic conditions to prevent oxidative degradation.

- Confirm the expression of key assembly factors (e.g., frataxin for Fe-S clusters; heme synthases for heme a) in your host system [21] [20].

- Cause 2: Uncoupling of Electron Transfer from Proton Motive Force. Certain inhibitors can halt electron flow, but some compounds, like thermogenin or thyroxine, act as uncouplers. They dissipate the proton gradient across the membrane, allowing electron transport to continue without ATP synthesis, which can be misinterpreted as low "efficiency" in some assays [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Inefficient Electron Transfer in Engineered Enzymes

| Observation | Possible Root Cause | Experimental Diagnostics | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low electrocatalytic current in a bioelectrode system. | Suboptimal enzyme orientation on electrode surface. | Measure the effect of different immobilization chemistries (e.g., His-tag vs. cysteine linkage) on current density. [22] | Employ site-specific immobilization strategies to control and unify enzyme orientation on the electrode. [22] |

| Excessive distance between the electrode and the enzyme's active cofactor. | Analyze the protein structure to measure the distance from the target cofactor to the protein surface. [22] | Use protein truncation to remove superficial domains and bring the cofactor closer to the surface. [22] | |

| Incorrect redox potential tuning of the cofactor. | Perform spectroelectrochemistry to determine the formal potential of the engineered cofactor. [22] | Use site-directed mutagenesis to alter the cofactor's protein environment (e.g., changing H-bonding networks) to adjust its redox potential. [23] | |

| High background signal or non-specific binding in biosensing. | Non-specific protein adsorption on the electrode. | Compare signal output before and after blocking steps with inert proteins (e.g., BSA). | Engineer a highly charged or polar protein surface to reduce hydrophobic interactions with the electrode. |

| Loss of enzyme activity over time. | Cofactor instability or leakage. | Monitor the absorption spectrum of the enzyme over time to detect loss of heme or Fe-S clusters. [20] | Incorporate strategies to strengthen cofactor binding, such as engineering additional coordinating residues or covalent linkages (inspired by c-type heme synthesis). [21] |

Guide 2: Addressing Cofactor-Related Deficiencies in Recombinant Protein Expression

| Observation | Possible Root Cause | Experimental Diagnostics | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression of an insoluble or misfolded recombinant heme protein. | Lack of heme availability during protein folding. | Check for a pale color in the cell pellet and purified protein. Use pyridine hemochrome assay to quantify heme content. [21] | Co-express heme biosynthesis pathway genes. Supplement growth media with ALA (5-aminolevulinate), a heme precursor. [20] |

| Recombinant Fe-S cluster protein lacks activity. | Oxidative degradation of the Fe-S cluster. | Characterize protein by EPR spectroscopy and UV-Vis spectroscopy to confirm the absence of Fe-S clusters. [20] | Express protein in a specialized bacterial strain with enhanced Fe-S cluster biogenesis machinery. Purify protein under strict anaerobic conditions. [20] |

| Incomplete assembly of a multi-subunit complex (e.g., Complex III). | Failure of covalent heme attachment to the protein backbone. | Use denaturing gel electrophoresis (e.g., SDS-PAGE) to check for the characteristic heme-associated peroxidase activity of the cytochrome subunit. [21] | Ensure the expression of the maturation machinery, such as cytochrome c heme lyase, which catalyzes the covalent attachment of heme to the CxxCH motif in apo-cytochromes. [21] |

Quantitative Data on Electron Transport Cofactors

Table 1: Key Properties of Electron Transport Chain Cofactors and Complexes

| Complex / Cofactor | Cofactor Type(s) | Electron Path / Function | Protons Pumped per 2 eâ» | Key Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) | FMN, [2Fe-2S], [4Fe-4S] clusters (up to 10 total) [20] | NADH → FMN → Fe-S clusters → Q [1] | ~4 H+ [18] [1] | Rotenone [18] |

| Complex II (Succinate dehydrogenase) | FAD, [2Fe-2S], [4Fe-4S], [3Fe-4S], Heme b [21] [19] | Succinate → FAD → Fe-S clusters → Q (via heme b) [21] | 0 [18] [1] | Malonate, Atpenin A5 |

| Complex III (Cytochrome bcâ‚ complex) | Heme bL, Heme bH, Heme câ‚, [2Fe-2S] (Rieske protein) [19] | QHâ‚‚ → [2Fe-2S] → Cyt c₠→ Cyt c (Q-cycle) [18] | 4 H+ (2 per Q-cycle turn) [1] | Antimycin A, Myxothiazol |

| Complex IV (Cytochrome c oxidase) | Heme a, Heme a₃, Cuâ‚, CuB [18] [1] | Cyt c → Cu₠→ Heme a → Heme a₃/CuB → Oâ‚‚ [18] | 4 H+ [18] [1] | Cyanide, Azide, Carbon Monoxide |

Table 2: Spatial and Thermodynamic Parameters for Electron Transfer Engineering

| Parameter | Typical Range in Biological Systems | Experimental Consideration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max Electron Tunneling Distance | ~20 Ã… | Distances beyond this require multi-step hopping via intermediate cofactors. | [22] |

| Heme Redox Potential Tuning | Can be tuned over a wide range by the protein environment. | Mutations in the binding pocket can drastically alter kinetics. A single mutation (PsaA-F689N) changed phylloquinone oxidation lifetime by ~100-fold. | [21] [23] |

| Fe-S Cluster Inter-cluster Distance | ~9-11 Ã… (as in Complex II) | Optimal for efficient electron hopping between clusters within a protein. | [19] |

| Heme a vs. Heme b Potential | Heme a has a ~180 mV higher midpoint potential than its precursor, heme o. | The formyl group on heme a is critical for the function of terminal oxidases like Complex IV. | [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enhancing Direct Electron Transfer (DET) via Protein Truncation

Objective: To improve the efficiency of DET between a redox enzyme and an electrode by genetically removing a shielding protein domain, thereby reducing the electron tunneling distance.

Materials:

- Gene construct for the target enzyme (e.g., FAD-dependent glucose dehydrogenase or cellobiose dehydrogenase).

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit or Gibson assembly reagents.

- Heterologous expression system (e.g., E. coli).

- Purification reagents: Ni-NTA resin (for His-tagged proteins), dialysis tubing, appropriate buffers.

- Electrochemical setup: Potentiostat, gold or glassy carbon working electrode, reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), counter electrode.

Method:

- Rational Truncation Design:

- Analyze the protein's three-dimensional structure (from PDB or homology model). Identify domains that shield the internal electron transfer chain but are not essential for catalytic activity.

- Design a primer to delete the DNA sequence encoding the target domain, ensuring the remaining sequence maintains an open reading frame.

Genetic Engineering:

- Perform site-directed mutagenesis or a cloning step (e.g., using restriction enzymes or Gibson assembly) to create the truncated gene construct.

- Verify the construct by DNA sequencing.

Protein Expression and Purification:

- Express the full-length (wild-type) and truncated enzymes in your chosen expression system.

- Purify both proteins using standard affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins).

- Confirm purity and integrity via SDS-PAGE. Validate cofactor retention using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Electrochemical Characterization:

- Immobilize the wild-type and truncated enzymes on the working electrode. Use a consistent method (e.g., drop-casting, specific covalent attachment via engineered surface cysteines).

- Record cyclic voltammograms (CV) for both electrodes in a buffered solution with and without the enzyme's substrate (e.g., glucose).

- Key Measurements: Compare the catalytic current density and the onset potential for the reaction between the wild-type and truncated enzymes. An increase in current and/or a shift in onset potential indicates improved DET efficiency [22].

Protocol 2: Probing Electron Transfer Pathways via Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Objective: To investigate the role of specific amino acids in modulating electron transfer kinetics within a redox protein by introducing point mutations and analyzing the functional consequences.

Materials:

- Gene construct for the target protein (e.g., a cytochrome or photosystem I subunit).

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit.

- System for expressing and purifying the mutant protein (as in Protocol 1).

- Spectroscopic equipment: UV-Vis spectrophotometer, and if available, a stopped-flow apparatus or a pump-probe laser setup for transient kinetics [23].

Method:

- Target Selection:

- Based on structural data, identify amino acid residues that are in close proximity to a redox cofactor (e.g., heme, quinone, Fe-S cluster) and may influence its environment (e.g., H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic packing).

- Select residues for mutation (e.g., Phe689 in PsaA of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii photosystem I) [23].

Mutagenesis and Protein Production:

- Generate the desired point mutants (e.g., PsaA-F689N) using site-directed mutagenesis.

- Express and purify the mutant proteins alongside the wild-type control.

Functional Kinetics Assay:

- For photosynthetic complexes: Use time-resolved absorption spectroscopy (pump-probe). Initiate electron transfer with a short laser flash and monitor the absorption changes associated with the oxidation/reduction of specific cofactors over nanoseconds to microseconds.

- Measurement: For the PsaA-F689N example, you would monitor the oxidation kinetics of the phyllosemiquinone (PhQâ»). A significant slowdown (e.g., ~100-fold) in the mutant compared to wild-type directly implicates this residue in tuning the electron transfer pathway [23].

- For other systems: Use chemical reductants to pre-reduce the protein and then monitor the re-oxidation kinetics of a specific cofactor spectroscopically.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electron Transfer Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Rotenone | Specific inhibitor of Complex I; binds to the ubiquinone binding site. | Used to inhibit NADH-driven respiration and to study reverse electron transport (RET)-induced ROS production. [18] |

| Antimycin A | Specific inhibitor of Complex III; binds to the Qi site, preventing ubiquinone reduction. | Used to inhibit the Q-cycle and to induce superoxide production from Complex III. [18] [1] |

| Cyanide (CNâ») / Azide (N₃â») | Potent inhibitors of Complex IV; bind tightly to the heme a₃-CuB binuclear center. | Used to halt mitochondrial respiration and measure oxygen consumption in the presence of other substrate combinations. [1] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Enables precise introduction of point mutations into a gene of interest. | For creating targeted mutations in cofactor-binding pockets to study and tune electron transfer kinetics (e.g., PsaA-F689N). [22] [23] |

| Cyclic Voltammetry Setup (Potentiostat, Electrodes) | Measures the current response of an immobilized enzyme to a changing potential, characterizing DET. | Essential for quantifying the electrochemical performance and ET efficiency of engineered enzymes and biohybrid systems. [22] [6] |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Detects characteristic absorption spectra of redox cofactors (heme Soret band, Fe-S cluster absorbance). | Used to confirm cofactor incorporation, assess purity, and monitor cofactor stability during protein purification and storage. [21] |

| 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA) | A precursor in the heme biosynthetic pathway. | Supplemented in growth media to boost intracellular heme production, aiding the expression and correct folding of recombinant heme proteins. [20] |

| Mal-PEG12-NHS ester | Mal-PEG12-NHS ester, MF:C35H58N2O18, MW:794.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Marmin acetonide | Marmin acetonide, MF:C22H28O5, MW:372.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Analyzing Dynamic Protein Interaction Networks in Electroactive Microbes

Core Concepts: Understanding Dynamic PPI Networks

What are dynamic Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks and why are they crucial in electroactive microbes? Dynamic PPI networks capture how protein interactions change under different environmental conditions, such as oxygen availability. Unlike traditional analyses that only look at expression levels, dynamic networks reveal functional modules that activate specifically for extracellular electron transfer (EET), which is essential for applications in bioenergy and environmental remediation [24] [25].

What are the key functional modules involved in EET? Research on Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 reveals that under EET conditions, active networks are highly consistent and enriched with proteins involved in specific functional modules [25]:

- Translation Processes (G1): Includes translation elongation and initiation factor activity, and ribosomal constituents.

- Transcription Regulation (G2): Involves DNA-directed RNA polymerase activity.

- Energy and Metabolism (G3 & G4): Includes proton-transporting ATP synthase activity.

- Flagellar Proteins (G5): Related to cell motility.

- The Mtr Pathway: A classical EET pathway involving key cytochromes [25].

Troubleshooting FAQs

FAQ 1: My engineered electroactive strain shows poor current output in a microbial fuel cell. Which hub proteins should I investigate for potential bottlenecks?

This is likely due to an inefficiency in the electron transfer pathway. We recommend you investigate the central hub proteins that coordinate EET dynamics.

- Root Cause: The dynamics of protein interactions in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 primarily revolve around a few critical proteins. Despite environmental changes, two central hubs, SO0225 and SO2402, play crucial roles in coordinating interaction dynamics under oxygen-limited conditions [24] [25].

- Solution:

- Verify the expression and function of SO0225 and SO2402 in your engineered strain.

- Investigate the classical Mtr pathway (proteins MtrA, MtrB, MtrC, OmcA) as your primary target for optimization, as its activation stages are critical for EET [24] [25].

- Consider that the role of other key proteins can be dynamic. For example, the inner membrane cytochrome CymA, traditionally considered essential, may have a reduced role under low EET kinetic conditions. Assess your system's electron release rate to diagnose potential pathway switching [26].

FAQ 2: I am using protein engineering to improve Direct Electron Transfer (DET) to an electrode, but the electron transfer efficiency is low. What are the key factors I should optimize?

Low DET efficiency often stems from issues with redox-active site accessibility and orientation.

- Root Cause: Efficient DET requires the redox-active site of the enzyme to be sufficiently exposed and close to the electrode surface. The theoretical maximum distance for efficient electron tunneling is approximately 20 Ã… [22].

- Solution:

- Increase Active Site Exposure: Use protein truncation or deletion to remove insulating domains that bury the redox-active cofactors [22].

- Optimize Enzyme Orientation: Employ site-specific immobilization techniques (e.g., using cysteine-gold bonds or polyhistidine tag coordination) to control how the enzyme binds to the electrode, ensuring the active site is positioned favorably [22].

- Reduce Electron Distance: For multi-subunit enzymes, consider fusing an electron-transferring domain with a surface-exposed cofactor to the enzyme via a flexible peptide linker to create a more efficient electron conduit [22].

FAQ 3: My computational model for predicting PPIs in a non-model electroactive bacterium has poor accuracy. How can I improve it?

This is a common challenge when dealing with less-studied organisms.

- Root Cause: Traditional computational methods rely on sequence similarity and manually engineered features, which can fail with limited data for non-model organisms [27].

- Solution: Leverage modern deep learning frameworks that are better at handling complex, high-dimensional biological data.

- Use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Architectures like Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) or Graph Attention Networks (GATs) can effectively capture the local and global relationships within protein structures [27].

- Employ Transfer Learning: Utilize pre-trained protein language models (e.g., based on BERT or ESM) that have learned general protein properties from vast datasets, and fine-tune them on your specific organism [27].

- Multi-modal Integration: Combine different types of data, such as amino acid sequences, predicted structural information, and Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, to enrich the model's input features [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Condition-Specific Active Protein Network

Objective: To identify and visualize the active sub-network of protein interactions in an electroactive microbe under a specific condition (e.g., oxygen limitation) [25].

Materials and Reagents:

- Protein Interaction Data: Download high-confidence protein-protein interaction data for your organism from the STRING database (combined score ≥ 700) [25].

- Gene Expression Data: RNA-seq or microarray data from cells under the condition of interest (e.g., low oxygen) and a control condition (e.g., high oxygen) [25].

- Software Tools: PathExt tool for active pathway identification; Cytoscape (v3.9 or higher) for network visualization [25].

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Filter the PPI network from STRING using a high confidence score (e.g., 700) and an experimental score greater than 0 to ensure reliability [25].

- Active Network Construction: Input the filtered PPI network and the condition-specific gene expression data into the PathExt computational tool. This tool identifies the most dynamic pathways and integrates them into a single active protein network [25].

- Enrichment Analysis: Perform Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis on the proteins in the resulting active network using the PANTHER classification system. Use a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 to identify significantly enriched molecular functions [25].

- Visualization and Analysis: Import the active network into Cytoscape. Use its layout algorithms to visualize functional modules. Identify hub proteins by calculating network centrality measures (e.g., degree centrality) [25].

Protocol 2: Engineering a Protein for Enhanced Direct Electron Transfer (DET)

Objective: To modify a redox enzyme to improve its ability to transfer electrons directly to an electrode surface [22].

Materials and Reagents:

- Gene of Interest: The plasmid containing the gene for the target redox enzyme.

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit: For introducing specific mutations or truncations.

- Electrodes: Gold, glassy carbon, or other suitable electrode material.

- Immobilization Reagents: Depending on the method, this could include reagents for forming gold-sulfur bonds (for cysteine) or metal-chelating surfaces (for polyhistidine tags) [22].

Methodology:

- Rational Design:

- Truncation: Analyze the protein structure to identify domains that insulate the redox-active cofactors. Design primers to delete these domains or specific heme-binding sites at the DNA level [22].

- Fusion: Genetically fuse a soluble electron-transferring domain (e.g., a cytochrome domain with surface-exposed hemes) to your enzyme of interest using a flexible peptide linker [22].

- Expression and Purification: Express the engineered protein in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli) and purify it using standard chromatographic techniques.

- Site-Specific Immobilization:

- Cysteine Mutation: Introduce a cysteine residue at a rationally selected surface location near the active site.

- Electrode Functionalization: Immobilize the engineered protein on the electrode via a gold-sulfur bond (for gold electrodes) or other covalent/coordinative chemistry [22].

- Electrochemical Validation:

- Use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to detect a non-mediated catalytic current in the presence of the enzyme's substrate.

- Compare the limiting catalytic current density of the engineered enzyme to the wild-type to quantify the improvement in DET efficiency [22].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Active PPI Network Analysis Workflow

The following diagram outlines the computational workflow for constructing and analyzing a condition-specific active protein network.

Key EET Pathways inShewanella oneidensisMR-1

This diagram illustrates the core and dynamic electron transfer pathways, highlighting critical proteins and their relationships.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents, databases, and software for analyzing dynamic PPI networks in electroactive microbes.

| Item Name | Type/Function | Specific Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| STRING Database | Biological Database | A source of known and predicted protein-protein interactions for constructing the foundational PPI network [25] [27]. |

| PathExt Tool | Computational Algorithm | Identifies condition-responsive active pathways by integrating gene expression data with a static PPI network [25]. |

| Cytoscape | Network Visualization Software | Used for visualizing, analyzing, and annotating the constructed active protein interaction networks [25]. |

| PANTHER | Functional Classification Tool | Used for Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis to determine the biological functions of proteins in the active network [25]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Deep Learning Architecture | Used for advanced PPI prediction and network analysis, capable of learning from complex graph-structured biological data [27]. |

| CymA / MtrC / OmcA | Key Cytochrome Proteins | Critical targets for protein engineering in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 to understand and manipulate EET pathways [25] [26]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Molecular Biology Technique | Used for protein truncation, point mutations, or fusion tag insertion to engineer proteins for improved DET [22]. |

Protein Engineering Toolbox for Enhanced Electron Transport

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary structural factors controlling electron transfer (ET) efficiency between P450s and their redox partners (RPs)?

- Answer: The ET efficiency is primarily governed by the structure of the protein-protein interaction interface. Key factors include:

- Interface Geometry: The spatial arrangement and distance between the electron-donating cofactor (e.g., FMN in CPR) and the heme iron in the P450. Crystal structures show the FMN cofactor is positioned at the proximal face of the heme domain, with the FMN located 18.4 Ã… from the heme iron in bacterial P450BM-3 [28].

- Complementary Surface: The presence of charged and hydrophobic residues that form specific interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and salt bridges, to stabilize the complex. The interaction between the heme and flavin domains of P450BM-3 involves a few direct hydrogen bonds and one salt bridge [28].

- Conformational Dynamics: Redox partners like CPR exist in an equilibrium between compact and extended conformations. Shifting this equilibrium, for instance, toward a compact form upon reduction, can protect reduced cofactors and control electron flow [29].

FAQ 2: My engineered P450-RP system shows high substrate conversion but also high uncoupling (ROS formation). How can I troubleshoot this?

- Answer: High uncoupling indicates that electrons are being diverted to molecular oxygen instead of substrate oxidation. This is a classic sign of inefficient electron transfer. Focus your troubleshooting on:

- Substrate Binding: Verify that your substrate is bound correctly and in a productive orientation for catalysis. Poor binding or incorrect positioning can prevent the second proton-coupled electron transfer, leading to ROS release.

- Redox Partner Docking: Re-evaluate the engineered interaction interface. While the fusion may bring partners together, the relative orientation of the FMN and heme groups might be suboptimal for efficient electron tunneling. Use computational docking to assess the geometry [4].

- Electron Transfer Pathway: Investigate if the through-bond electron pathway to the heme iron is intact and efficient. Mutations near the heme-binding loop can disrupt this pathway [28].

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally monitor conformational changes in my redox partner (e.g., CPR) upon binding NADPH?

- Answer: Neutron reflectometry (NR) on membrane proteins reconstituted in Nanodiscs is a powerful, label-free method for this purpose. This technique can:

- Detect and quantify the coexistence of different conformational states (e.g., compact vs. extended) of the redox partner.

- Monitor shifts in the conformational equilibrium in response to changes in redox state, such as reduction by NADPH. Studies show reduction can shift the equilibrium from ~70% extended to ~60% compact in POR [29].

FAQ 4: What high-throughput methods are available for screening P450 variants with improved electron transfer?

- Answer: Modern high-throughput screening leverages compartmentalization and automation:

- Microfluidics: Drop-based microfluidic systems can screen thousands of variants per hour by encapsulating single cells or lysates in picoliter droplets, each acting as a microreactor [30].

- Flow Cytometry (FACS): When combined with yeast or mammalian surface display, FACS can sort large libraries of variants based on a fluorescent signal generated by enzymatic activity [30].

- Automated Purification: Low-cost, robot-assisted pipelines enable the parallel purification of 96s of protein variants, providing purified enzyme for accurate activity and coupling efficiency assays [31].

FAQ 5: Can computational design predict mutations that improve the P450-RP interface for better electron transfer?

- Answer: Yes, computational enzyme design frameworks are increasingly effective. For example:

- UniDesign is a workflow that can redesign enzyme active sites and interaction interfaces. It involves generating an ensemble of transition-state ligand poses, repacking the mutable residues around them, and scoring sequences with a composite energy function to find optimal mutants that enhance properties like stereoselectivity and, by extension, efficient coupling [32].

- These tools can scan active site residues and identify mutations that stabilize the binding of a specific substrate in an orientation optimal for catalysis, thereby improving coupling efficiency [32].

Summarized Quantitative Data

Table 1: Key Structural Parameters from the P450BM-3 Heme-FMN Domain Complex [28]

| Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Distance (FMN to Heme Iron) | 18.4 Ã… | Defines the electron tunneling distance for inter-domain ET. |

| Distance (FMN to Heme-Binding Loop) | 4.0 Ã… | Indicates close proximity to the efficient through-bond electron pathway. |

| Interface Area | 967 Ų | Suggests a relatively small and specific binding interface. |

| Direct Hydrogen Bonds | 2 | Contributes to the specificity and stability of the complex. |

| Salt Bridges | 1 | Provides electrostatic steering and stabilization for binding. |

Table 2: Conformational Equilibrium of Cytochrome P450 Reductase (POR) in Nanodiscs [29]

| Redox State | Compact Form | Extended Form | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Oxidized | ~30% | ~70% | Equilibrium favors the extended form, potentially for partner binding. |

| Fully Reduced (by NADPH) | ~60% | ~40% | Equilibrium shifts towards the compact form, protecting reduced FMN. |

| Molecular Thickness (Compact) | 44 â„« | - | - |

| Molecular Thickness (Extended) | 79 â„« | - | - |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Objective: To probe the NADPH-dependent conformational equilibrium of a membrane-bound cytochrome P450 reductase (POR) in a native-like lipid bilayer environment.

Materials:

- Purified, full-length cytochrome P450 reductase (POR).

- Lipids (e.g., DMPC).

- Membrane Scaffolding Protein (MSP).

- Neutron reflectometer.

- Silicon oxide surface.

Methodology:

- Reconstitution: Incorporate POR into Nanodiscs by mixing purified POR, lipids, and MSP at a controlled stoichiometry, followed by detergent removal to form monodisperse lipid bilayer discs encircled by the MSP belt.

- Sample Preparation: Physisorb the POR-containing Nanodiscs onto a silicon oxide surface to form a well-ordered, dense film.

- Data Collection:

- Perform neutron reflectivity (NR) measurements on the film under two conditions: (a) with POR in a fully oxidized state, and (b) with POR in a fully reduced state (after addition of NADPH).

- Use contrast variation (e.g., Hâ‚‚O vs. Dâ‚‚O buffers) to enhance sensitivity to the protein layer.

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the neutron reflectivity curves using a layered model of the film.

- The thickness and scattering length density of the POR layer will reveal the presence of two distinct conformations. The data is fit by considering a mixture of compact and extended forms, allowing for the quantification of their population shift upon reduction.

Objective: To screen a library of P450 variants for improved activity or coupling efficiency at high throughput.

Materials:

- Library of P450 variant expressing cells (e.g., E. coli) or cell lysates.

- Fluorogenic or chromogenic substrate for the P450 reaction.

- Drop-based microfluidic system.

- Surfactant for stabilizing water-in-oil emulsions.

Methodology:

- Library Preparation: Generate a diverse library of P450 mutants via directed evolution methods (e.g., error-prone PCR).

- Droplet Generation:

- Mix the cell suspension (or lysate) containing individual P450 variants with the assay substrate and cofactors.

- Inject this aqueous mixture into a microfluidic device along with a continuous oil phase containing surfactant.

- The device will generate monodisperse water-in-oil droplets, each encapsulating a single variant and the reagents for the reaction.

- Incubation & Detection: Flow the droplets through a delay line on the chip to allow time for the enzymatic reaction to occur. As droplets pass through a detection point, a laser excites fluorescence, and a detector measures the signal intensity from each droplet.

- Sorting: Based on the fluorescence signal (which correlates with activity), an electrical field can be applied to deflect and sort droplets containing the most active variants into a collection tube for recovery and sequencing. Throughputs can exceed 1,000 droplets per second [30].

Essential Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for P450-Redox Partner Engineering

| Item | Function/Benefit | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nanodisc Technology | Provides a stable, monodisperse native-like membrane environment for studying membrane-bound P450s and redox partners like POR. | Neutron reflectometry studies to probe conformational dynamics [29]. |

| Low-Cost Liquid-Handling Robot (e.g., Opentrons OT-2) | Automates tedious pipetting steps, enabling parallel purification of 96s of enzyme variants with high reproducibility and reduced waste. | High-throughput screening and characterization of engineered P450 variants [31]. |

| UniDesign Software Framework | A computational enzyme design tool that scans for mutations to stabilize transition states and optimize active site configurations. | Redesigning P450 active sites for improved stereoselectivity and electron coupling [32]. |

| Fluorogenic/Microfluidic Substrates | Enzyme substrates that generate a fluorescent signal upon turnover, compatible with ultra-high-throughput screening in microfluidic droplets. | Screening large mutant libraries for activity in drop-based microfluidic systems [30]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Gold Films | Platform for controlled, covalent immobilization of P450s, allowing study of homomeric and heteromeric P450-P450 interactions. | Investigating how P450 oligomerization affects metabolic activity [33]. |

| Benzyl-PEG5-NHBoc | Benzyl-PEG5-NHBoc, MF:C22H37NO7, MW:427.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pseudolaroside A | Pseudolaroside A, MF:C13H16O8, MW:300.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Catalytic Efficiency of Fusion Enzyme

- Problem: The constructed fusion enzyme shows significantly lower activity than the individual enzyme components or a simple enzyme mixture.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Cause: Suboptimal linker length or rigidity disrupting the spatial orientation of protein domains, hindering electron transfer or substrate channeling [34] [35].

- Solution: Systematically test linkers of different lengths and flexibilities. For instance, a study on a P450 monooxygenase chimera found that a flexible linker comprising 15 amino acids yielded the highest reduction activity, which was 26.6% greater than the natural electron transfer system [34]. Consider rigid α-helical linkers for fixed domain separation or flexible glycine-serine (GS) linkers for dynamic movement.

Issue 2: Insufficient Cofactor Regeneration or High Cofactor Input

- Problem: The fusion enzyme requires an impractically high concentration of expensive cofactors (e.g., NADPH) to function efficiently.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Cause: Cofactor diffusion away from the enzyme complex before it can be regenerated by the fused reductase domain [35].

- Solution: Engineer a peptide bridge for cofactor channeling. A 2025 study designed a decapeptide linker (R10) with high affinity for NADPH to bridge PAMO and PTDH enzymes. This construct reduced NADPH input by two orders of magnitude and increased conversion 2.1-fold compared to the free enzyme system by creating electrostatic cofactor channeling [35].

Issue 3: Fusion Protein Misfolding or Aggregation

- Problem: The fusion protein is expressed insolubly or forms aggregates.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Cause: Incompatible interactions between the fused protein domains or hydrophobic patches exposed by the linker.

- Solution: Introduce stabilizing point mutations or alter the fusion order. Research shows that the order of nanobody and antigen fusion to ferredoxin fragments significantly affected cellular electron transfer [36]. If one configuration fails, try inverting the domain order (e.g., Domain A-Linker-Domain B vs. Domain B-Linker-Domain A).

Issue 4: Electron Transfer Not Regulated by Inducer

- Problem: An engineered switchable fusion protein, designed to turn on electron transfer upon binding a macromolecule, shows constitutive activity or no activity.

- Potential Cause & Solution:

- Cause: The fusion strategy or the specific nanobody homolog used does not effectively couple antigen binding to the protein's functional state [36].

- Solution: Explore different fusion strategies (e.g., split proteins vs. domain insertion) and multiple nanobody homologs. One study found that only specific anti-GFP nanobody insertions into ferredoxin resulted in variants whose electron transfer could be switched on by GFP co-expression [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key considerations when selecting a peptide linker for a fusion construct? A: The choice depends on the desired function:

- Flexibility: Use flexible, unstructured linkers (e.g., rich in Gly and Ser) to allow dynamic movement and domain interaction [34].

- Rigidity: Use rigid, α-helical linkers (e.g., from α-helix-rich proteins) to maintain fixed distances and prevent unwanted domain interactions.

- Length: The linker must be long enough to allow proper folding of both domains but short enough to enable efficient function. This often requires empirical testing (e.g., trying 5, 10, 15, 20 amino acids) [34].

- Functionality: For advanced functions like substrate channeling, design "smart" linkers with specific chemical properties (e.g., cation-rich peptides to guide anionic cofactors like NADPH) [35].

Q2: How can I experimentally validate that my fusion construct creates a functional cofactor channeling system? A: Beyond measuring increased product yield, you can:

- Competitive Side Reaction Test: Introduce a competing enzyme that consumes the channeled cofactor (e.g., NADPH) into the reaction system. A channeling system will be less affected by this competitor than a free enzyme system, as the cofactor is protected [35].

- Ionic Strength Assay: Perform reactions at varying salt concentrations. Electrostatic channeling efficiency often decreases with increasing ionic strength, as salt ions shield the attractive forces between the linker and the cofactor [35].

Q3: Can fusion constructs be used for purposes other than enhancing catalytic rates? A: Absolutely. Fusion constructs are versatile tools for:

- Improving Stability: Enhancing resistance to aggregation, denaturation, or proteolytic degradation [37] [38].

- Enabling Regulation: Creating protein switches whose activity is controlled by small molecules or macromolecular binding [36].

- Facilitating Purification: Fusing to tags like His-tags or GST-tags.

- Altering Pharmacokinetics: For therapeutic proteins, fusions can increase circulation half-life in vivo [38].

Q4: What should I do if my fusion protein is expressed but is inactive? A: Follow a systematic diagnostic approach:

- Check Individual Domain Folding: Use techniques like circular dichroism (CD) to confirm that both protein domains in the fusion retain their native secondary structure.

- Verify Cofactor/Prosthetic Group Incorporation: For metalloenzymes (e.g., P450s, ferredoxins), ensure that the heme or iron-sulfur cluster is properly incorporated into the fusion protein [36].

- Test Linker Accessibility: The linker may be buried or causing steric hindrance. Try a different linker sequence or length.

- Confirm Fusion Strategy: For electron transfer proteins, the fusion order is critical. Try alternative architectures (e.g., N-terminal vs. C-terminal fusions of reductase domains) [34] [36].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Different Fusion Constructs

| Fusion Enzyme System | Linker Type | Key Performance Metric | Result with Fusion Construct | Control System Result | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP11B1-BMR Chimera | 15-amino acid flexible linker | Catalytic efficiency (using 7-ethoxycoumarin) | Increased by 30% | CYP11B1-AdR/Adx (natural system) | [34] |

| PAMO-PTDH Fusion (FuE-R10) | Cationic decapeptide (R10) | NADPH input required | Reduced by ~100x (two orders of magnitude) | Free enzyme mixture | [35] |

| PAMO-PTDH Fusion (FuE-R10) | Cationic decapeptide (R10) | Product conversion (low NADPH) | 2.1-fold higher | Free enzyme mixture (FuE-R10 vs. Free Enzymes) | [35] |

| PAMO-PTDH Fusion (FuE-GS10) | Flexible (GS)(_{10}) linker | Product conversion (low NADPH) | ~1.05-fold higher | Free enzyme mixture (FuE-GS10 vs. Free Enzymes) | [35] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Fusion Enzyme Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cationic Peptide Linkers | Creates an electrostatic channel for anionic cofactors (e.g., NADPH) to enhance transport between active sites. | Fusing oxidoreductases like PAMO and PTDH for efficient NADP(H) recycling [35]. |

| Nanobody-Antigen Pairs | Acts as a molecular switch; antigen binding induces conformational change to regulate activity. | Engineering ferredoxins whose electron transfer is activated by GFP binding [36]. |

| Fe-S Cluster (e.g., in Ferredoxin) | Serves as an electron carrier in redox reactions. | Core component for building engineered electron transfer chains in metabolic pathways [36]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduces point mutations to improve stability (e.g., prevent aggregation) or tune activity. | Creating long-acting insulin variants or antibodies with enhanced half-life [38]. |

Detailed Protocol: Engineering a Fusion Enzyme for Cofactor Channeling

This protocol is adapted from studies on constructing fusions with peptide bridges for NADPH channeling [35].

Objective: To fuse two NADP(H)-dependent enzymes (e.g., a monooxygenase and a dehydrogenase) using a specifically designed peptide linker to achieve cofactor channeling and reduce NADPH input.

Materials:

- Plasmid DNA for the two target enzymes (e.g., PAMO and PTDH genes).

- Cloning reagents: restriction enzymes, ligase, or Gibson assembly mix.

- Expression host (e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3)).

- Equipment for MD simulations (optional but recommended for linker design).

- Chromatography system for protein purification (e.g., Ni-NTA if using His-tag).

- Substrates for both enzymes and NADPH.

- HPLC or GC-MS for product quantification.

Methodology:

- Linker Design via Virtual Screening:

- Compile a library of candidate peptide linkers (e.g., 10-mer peptides).

- Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to rank the linkers based on their binding affinity (e.g., Gibbs free energy, ΔG) for the cofactor (NADPH). Select the linker with the strongest predicted affinity for experimental testing [35].

- Genetic Construction:

- Design DNA constructs encoding Enzyme A - [Selected Linker] - Enzyme B. Include a control construct with a standard flexible linker (e.g., (GGS)(_{n})).

- Assemble the final construct into an appropriate expression vector using standard molecular biology techniques (e.g., Golden Gate assembly, PCR stitching).

- Protein Expression and Purification:

- Transform the expression host with the fusion construct plasmids.

- Induce protein expression with IPTG or autoinduction media.

- Lyse cells and purify the fusion protein using affinity chromatography.

- Confirm protein integrity and concentration via SDS-PAGE and spectrophotometry.

- Functional Characterization:

- Activity Assay: Perform the coupled reaction (e.g., Baeyer-Villiger oxidation catalyzed by PAMO, with NADPH regeneration by PTDH). Compare the initial reaction rates and final product yields of the fusion enzyme against a free enzyme mixture.

- Cofactor Titration: Repeat the activity assay at progressively lower NADPH concentrations (e.g., from 100 µM down to 1 µM). A functional channeling system will maintain high conversion efficiency even at very low cofactor:enzyme ratios.

- Competitive Inhibition Test: Add a competing NADPH-consuming enzyme (e.g., glutathione reductase) to the reaction. A channeling system will show higher resistance to this inhibition.

- Ionic Strength Test: Perform assays at different NaCl concentrations (e.g., 0-500 mM). Efficiency in an electrostatically channeled system is expected to decrease with increasing ionic strength.

Visualizing Fusion Construct Strategies

Fusion Architectures and Workflow

Cofactor Channeling Mechanism

Direct Evolution and High-Throughput Screening for Electron Transfer Traits

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental differences between screening and selection in directed evolution?

Answer: Screening and selection are the two main methods for analyzing mutant libraries in directed evolution, differing primarily in throughput and methodology.