Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Redox Sensing: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Biosensor Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) applied to redox-based sensing, a critical technique for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Redox Sensing: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Biosensor Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) applied to redox-based sensing, a critical technique for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of EIS and the Randles circuit, explores advanced methodologies for designing faradaic EIS biosensors, and addresses common troubleshooting and data validation strategies. By integrating recent advances, including machine learning for automated analysis and modified equivalent circuits for complex bio-interfaces, this guide serves as a vital resource for developing robust, high-sensitivity biosensors for applications from therapeutic drug monitoring to point-of-care diagnostics.

Understanding EIS and Redox Sensing: Core Principles and the Randles Circuit

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique that investigates the dynamic behavior of electrochemical systems by measuring their impedance across a range of frequencies. This method provides detailed information about electrode processes, reaction kinetics, and material properties that are essential for redox sensing research and drug development applications [1]. Unlike traditional DC techniques that apply static signals, EIS utilizes a small-amplitude alternating current (AC) perturbation to probe system characteristics without causing significant damage or alteration to the sample being tested [2].

The foundation of EIS begins with Ohm's Law, which defines the relationship between voltage, current, and resistance in DC circuits. However, when studying electrochemical systems under AC conditions, the concept of resistance expands to the more comprehensive principle of impedance [3]. This transition from simple resistive behavior to complex impedance enables researchers to characterize diverse electrochemical processes including charge-transfer kinetics, double-layer capacitance, and diffusion processes that are critical in pharmaceutical research and biosensor development [1].

For researchers in drug development, EIS offers particular advantages for non-destructive testing of biological samples, monitoring binding events in biosensors, and characterizing biomaterials. The technique's sensitivity to interfacial properties makes it invaluable for studying molecular interactions, protein binding, and cellular responses that are relevant to pharmaceutical applications [4].

Theoretical Foundations: From DC Resistance to AC Impedance

Ohm's Law and Its Limitations in Electrochemistry

Ohm's Law establishes the fundamental relationship between voltage (E), current (I), and resistance (R) in DC circuits through the equation E = I × R [3]. In this context, resistance represents a circuit element's opposition to direct electrical current flow. While this concept works well for ideal resistors, it fails to adequately describe the behavior of real-world electrochemical systems, which exhibit more complex characteristics including frequency-dependent behavior and phase shifts between voltage and current signals [2].

The limitation of simple resistance becomes apparent when dealing with capacitive and inductive elements common in electrochemical cells. Ideal resistors follow Ohm's Law at all current and voltage levels, maintain constant resistance regardless of frequency, and produce current and voltage signals that remain perfectly in phase. Electrochemical systems rarely display these ideal characteristics, necessitating a more comprehensive approach to characterize their electrical behavior [2].

Complex Impedance in AC Systems

Impedance (Z) extends the concept of resistance to AC systems and represents the total opposition a circuit presents to alternating current flow. The mathematical definition of impedance parallels Ohm's Law but incorporates complex number notation: Z(ω) = E(ω)/I(ω), where E(ω) is the AC voltage signal and I(ω) is the resulting AC current response at angular frequency ω [2] [1].

In an EIS experiment, researchers apply a sinusoidal potential excitation signal: E(t) = E₀ × sin(ωt + Φ), where E₀ is the amplitude, ω is the radial frequency, t is time, and Φ represents the phase angle. The system responds with a current signal at the same frequency but potentially shifted in phase: I(t) = I₀ × sin(ωt + θ) [3] [2]. The impedance is then calculated from the ratio of voltage to current amplitudes and the phase difference between the signals.

Table 1: Fundamental EIS Parameters and Their Significance

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Physical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Resistance | Rₛ | Ω (Ohms) | Resistance of ionic current path through electrolyte |

| Charge Transfer Resistance | R꜀ₜ | Ω (Ohms) | Kinetic barrier to electron transfer at electrode interface |

| Double-Layer Capacitance | C꜀ₗ | F (Farads) | Capacitance from charge separation at electrode-electrolyte interface |

| Warburg Impedance | Z_w | Ω·sâ»â°Â·âµ | Resistance related to diffusion-controlled mass transport |

| Constant Phase Element | Q | S·sâ¿ (Siemens·secâ¿) | Non-ideal capacitive element accounting for surface heterogeneity |

The impedance value Z(ω) can be separated into real (Z') and imaginary (Z") components using Euler's relationship: Z(ω) = Z' + jZ", where j is the imaginary unit (√-1) [2]. This complex number representation enables the description of both the magnitude of opposition to current flow and the phase relationship between voltage and current signals, providing comprehensive information about the electrochemical system under investigation.

EIS Measurement Principles and Data Representation

Experimental Setup and Measurement Process

A typical EIS experimental setup requires several key components: a potentiostat or galvanostat with EIS capability, a three-electrode cell configuration (working electrode, reference electrode, and counter electrode), an electrolyte solution, and environmental controls to maintain stable measurement conditions [1]. For redox sensing applications in pharmaceutical research, the working electrode is often functionalized with specific recognition elements such as molecularly imprinted polymers or biological receptors to enhance selectivity toward target analytes [5].

The measurement process involves applying a sinusoidal potential signal with small amplitude (typically 5-10 mV) to maintain system linearity [2] [1]. This excitation signal is applied across a range of frequencies, typically from millihertz (mHz) to megahertz (MHz), with the current response measured at each frequency point. Modern EIS systems often perform measurements in the time domain, then apply a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to convert the data into the frequency domain for analysis [3] [2].

For reliable EIS measurements, the electrochemical system must remain at steady state throughout the measurement period, which can extend from minutes to hours depending on the frequency range covered. System drift due to factors such as adsorption of solution impurities, growth of oxide layers, buildup of reaction products, or temperature fluctuations can compromise data quality and lead to inaccurate interpretation [2].

Data Representation Methods

EIS data can be visualized using several plotting conventions, with Nyquist and Bode plots being the most common representations. Each format presents complementary information about the system's impedance characteristics.

Nyquist Plots display the negative imaginary impedance (-Z") on the vertical axis against the real impedance (Z') on the horizontal axis [3] [2]. Each point on the Nyquist plot represents the impedance at one frequency, with higher frequencies typically appearing on the left side of the plot and lower frequencies on the right. While Nyquist plots efficiently illustrate the system's impedance response, they do not explicitly show frequency information, which represents a significant limitation [2].

Bode Plots present impedance magnitude (|Z|) and phase angle (θ) as functions of frequency, typically using logarithmic scales for both frequency and impedance magnitude [3] [2]. These plots explicitly show frequency dependence, making them valuable for identifying characteristic frequencies and time constants within the electrochemical system. The phase angle plot is particularly useful for distinguishing between different electrochemical processes based on their frequency response.

Table 2: Comparison of EIS Data Representation Methods

| Plot Type | Axes | Advantages | Limitations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyquist Plot | X: Z' (Real), Y: -Z" (Imaginary) | Compact representation, easy visualization of circuit elements | No explicit frequency information | ||

| Bode Plot (Magnitude) | X: log(f), Y: log( | Z | ) | Shows frequency dependence, wide dynamic range | Relationship between processes less obvious |

| Bode Plot (Phase) | X: log(f), Y: θ (degrees) | Identifies characteristic time constants | May not show all processes clearly |

EIS Measurement Workflow

Equivalent Circuit Modeling and Data Interpretation

Common Circuit Elements

Interpreting EIS data typically involves modeling the electrochemical system using equivalent electrical circuits composed of elements that represent physical processes. The most common circuit elements used in these models and their impedance functions include:

- Resistor (R): Represents purely resistive behavior with impedance Z_R = R, independent of frequency. In electrochemical systems, resistors often model solution resistance (Rₛ) or charge transfer resistance (R꜀ₜ) [2].

- Capacitor (C): Represents ideal capacitive behavior with impedance Z_C = 1/(jωC). Capacitors typically model the double-layer capacitance at the electrode-electrolyte interface [2].

- Constant Phase Element (CPE): Accounts for non-ideal capacitive behavior often observed in real electrochemical systems due to surface heterogeneity, roughness, or porosity. Its impedance is defined as Z_CPE = 1/[Q(jω)â¿], where Q is the CPE constant and n is the phase element exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1) [6].

- Warburg Element (W): Models semi-infinite linear diffusion with impedance ZW = AW/√ω × (1-j), where A_W is the Warburg coefficient. This element appears as a 45° line in Nyquist plots [6].

Common Equivalent Circuit Models

The Randles circuit represents one of the most fundamental equivalent circuit models used in EIS analysis of electrochemical systems. This model includes solution resistance (Rₛ) in series with a parallel combination of charge transfer resistance (R꜀ₜ) and double-layer capacitance (C꜀ₗ) [6]. For diffusion-controlled processes, the Randles circuit expands to include a Warburg element (W) in series with R꜀ₜ.

For more complex systems such as coated metals or biological interfaces, additional circuit elements are incorporated. A common model for damaged coatings includes a pore resistance (Rₚₒ) in parallel with the coating capacitance (C꜀), with this combination in series with a parallel R꜀ₜ-C꜀ₗ circuit representing the exposed metal surface [7].

Circuit Models and Applications

Experimental Protocol: EIS for Biosensing Applications

Sensor Fabrication and Preparation

This protocol describes the development of an electrochemical biosensor for Vitamin D3 detection using molecularly imprinted polymers (MIP) and EIS detection, based on recently published research [5]. The procedure can be adapted for various redox sensing applications in pharmaceutical research.

Materials and Reagents:

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCE) or appropriate electrode system

- Dopamine hydrochloride for polymer formation

- MoSeâ‚‚ nanosheets (synthesized via hydrothermal method)

- Vitamin D3 standard (target analyte)

- Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide redox probe ([Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â»)

- Tris-base buffer (pH 8.0)

- Other chemical reagents: sodium molybdate dihydrate, selenium powder, hydrazine hydrate

Equipment:

- Potentiostat with EIS capability (frequency response analyzer)

- FT-IR spectrometer for chemical characterization

- XRD analyzer for structural characterization

- SEM/TEM for morphological analysis

- Standard laboratory equipment: centrifuges, oven, ultrasonic bath

Sensor Fabrication Procedure:

- Synthesis of MoSe₂ nanosheets: Dissolve 6 g sodium molybdate dihydrate in 25 mL deionized water. Separately, dissolve 1.2 g selenium powder in 5 mL hydrazine hydrate with 30 minutes stirring. Combine both solutions and stir for 1 hour. Transfer to Teflon-lined autoclave and heat at 200°C for 24 hours. Cool to room temperature, centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, and dry pellet at 80°C [5].

Preparation of MIP@MoSe₂ composite: Dissolve 40 mg dopamine hydrochloride in 20 mL Tris-base buffer (pH 8.0). Add 1 mL MoSe₂ nanosheet suspension and 1 mL Vitamin D3 stock solution (template). Stir overnight (~18 hours) for polymerization. Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes and wash thoroughly with deionized water until supernatant is neutral, colorless, and odorless. Dry at 80°C [5].

Template removal: Sonicate the synthesized MIP@MoSeâ‚‚-Vitamin D3 composite for 12 hours to remove the template molecules, creating specific recognition sites.

Electrode modification: Deposit the MIP@MoSeâ‚‚ composite onto screen-printed carbon electrodes and allow to dry under controlled conditions.

EIS Measurement and Data Analysis

Experimental Conditions:

- Electrolyte: 20 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» in appropriate buffer solution

- Frequency range: 10 mHz - 100 kHz (or 0.001 Hz - 10âµ Hz)

- AC amplitude: 10 mV

- DC potential: Open circuit potential or formal potential of redox probe

- Temperature: Controlled at 25°C (unless otherwise specified)

EIS Measurement Procedure:

- System validation: Verify potentiostat performance using open-lead tests and standard resistor-capacitor circuits [7].

- Baseline measurement: Record EIS spectrum of modified electrode in supporting electrolyte without target analyte.

- Sample measurement: Incubate modified electrode with Vitamin D3 standard solutions or unknown samples for predetermined time (15-30 minutes).

- EIS recording: Measure impedance spectrum in redox probe solution using parameters above.

- Data collection: Record impedance magnitude and phase angle at each frequency, or collect real and imaginary impedance components directly.

Data Analysis Steps:

- Data validation: Apply Kramers-Kronig transformations to verify data quality and consistency [6].

- Circuit modeling: Fit experimental data to appropriate equivalent circuit model using nonlinear least-squares fitting algorithm.

- Parameter extraction: Obtain values for circuit elements (Rₛ, R꜀ₜ, CPE, etc.) from best-fit parameters.

- Quantification: Plot charge transfer resistance (R꜀ₜ) or other relevant parameters against analyte concentration to generate calibration curve.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EIS Biosensing

| Reagent/Solution | Composition/Preparation | Primary Function | Storage Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redox Probe Solution | 1-20 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] in buffer | Provides reversible electron transfer for impedance measurement | 4°C, protected from light |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer | Polydopamine@MoSeâ‚‚ with template | Selective recognition of target analyte | Dry, airtight container |

| Electrode Cleaning Solution | Diluted acid or solvent appropriate to electrode material | Removes contaminants from electrode surface | Room temperature |

| Buffer Solution | Phosphate or Tris buffer, pH 7.4 | Maintains consistent pH environment | 4°C |

Advanced Applications in Redox Sensing and Drug Development

EIS has emerged as a powerful technique in pharmaceutical research and biosensing due to its label-free detection capability, high sensitivity, and ability to monitor binding events in real-time. Recent advances have demonstrated particularly valuable applications in several key areas:

Drug Target Interaction Studies: EIS enables real-time monitoring of molecular interactions between pharmaceutical compounds and their biological targets. Researchers have successfully employed EIS to study protein-drug interactions, antibody-antigen binding, and receptor-ligand interactions without requiring fluorescent or radioactive labeling [1] [5]. The technique detects changes in interfacial properties at functionalized electrode surfaces when binding events occur, providing information about binding affinity, kinetics, and concentration.

Biosensor Development for Clinical Diagnostics: The high sensitivity of EIS has been leveraged for developing clinical diagnostic sensors for various biomarkers. Recent research demonstrates successful EIS-based detection of Vitamin D3 with a linear range of 25-200 ng/mL and detection limit of 0.69 ng/mL, showcasing the technique's relevance to pharmaceutical analysis [5]. Similarly, EIS has been applied for early detection of oral potentially malignant disorders and oral cancer, achieving area under curve (AUC) values of 0.91 in clinical validation studies [4].

Machine Learning-Enhanced EIS Analysis: Advanced data analysis approaches incorporating machine learning have significantly improved EIS interpretation capabilities. Recent studies demonstrate automated equivalent circuit model selection with 96.32% classification accuracy using global heuristic search algorithms and hybrid optimization methods [6]. For passive metal classification, machine learning frameworks combining principal component analysis with k-nearest neighbors classifiers have achieved robust classification of surface states from limited EIS datasets [8]. These approaches reduce subjectivity in traditional EIS analysis and enhance reproducibility for pharmaceutical applications.

The integration of EIS with advanced nanomaterials, microfluidic systems, and machine learning algorithms continues to expand its applications in drug development, enabling high-throughput screening, point-of-care diagnostics, and sophisticated biomolecular interaction studies relevant to pharmaceutical research and development.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) has emerged as a powerful, label-free technique for quantifying a vast array of analytes, from small drug molecules to large biomarkers, directly in complex biological matrices. Within this domain, Faradaic EIS distinguishes itself by employing a soluble redox probe to generate a highly sensitive, measurable signal that correlates directly with analyte concentration. This signal manifests as a change in the charge transfer resistance (Rct), which is highly sensitive to modifications and binding events occurring at the electrode surface [9] [10]. The core principle involves monitoring the perturbation in the electron transfer efficiency of the redox probe caused by the presence of the target analyte. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on EIS redox sensing, details the fundamental principles, practical protocols, and critical considerations for leveraging redox probes to establish a robust correlation between impedimetric signal and analyte concentration for researchers and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations & Key Concepts

In a typical Faradaic EIS experiment, a small sinusoidal AC potential (typically 5-10 mV amplitude) is applied across a range of frequencies, and the resulting current response is measured. The data is commonly presented as a Nyquist plot, where the imaginary component of impedance (-Z'') is plotted against the real component (Z') [9] [10]. The resulting spectrum often features a semicircular region at higher frequencies, corresponding to the electron transfer-limited process, and a linear region at lower frequencies, representing diffusion-limited processes. The diameter of the semicircle is quantitatively equivalent to the Rct [9].

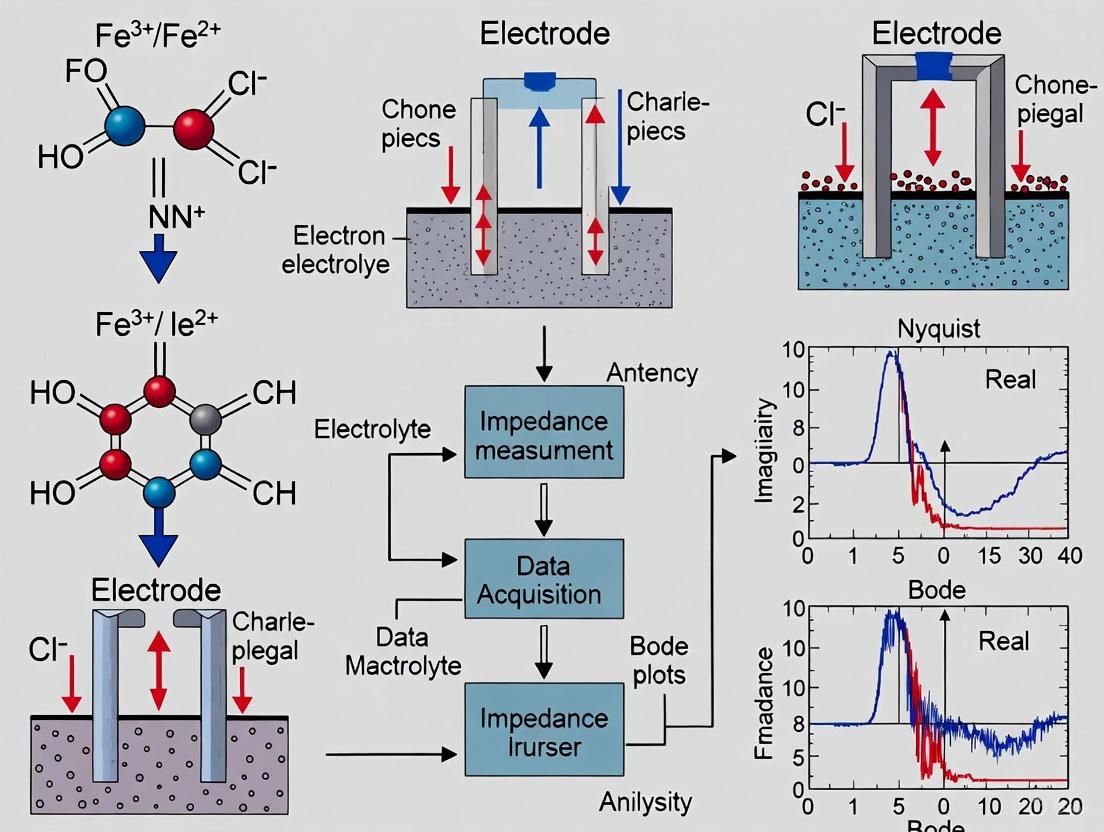

The introduction of a redox-active species, or a redox probe, is what enables the Faradaic process. Commonly used probes include ferro/ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)6]3−/4−) and hexaammineruthenium ([Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+). When the target analyte interacts with the sensor surface—be it through binding, blocking, or altering the interface—it impedes the redox probe's access or electron transfer kinetics. This obstruction causes a measurable increase in the Rct value, providing the quantitative foundation for sensing [11] [10]. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling mechanism of a Faradaic EIS biosensor.

The electrical characteristics of the electrode-electrolyte interface in a Faradaic EIS system are accurately modeled by an equivalent circuit. The most common model is the Randles-Ershler equivalent circuit, which includes the following components [9] [11] [10]:

- Rs: The solution resistance.

- Cdl: The double-layer capacitance.

- Rct: The charge-transfer resistance.

- W: The Warburg impedance, representing diffusion.

In this circuit, the Rct is the parameter most directly influenced by surface binding events and is therefore the primary correlate for analyte concentration.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electrode Modification and Sensor Fabrication (Exemplified for a Metallic Nanoparticle-Based Sensor)

This protocol outlines the fabrication of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) modified with oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) for the detection of a thiol-containing drug, adapted from a published sensor for Mesna [11].

- Aim: To create a high-sensitivity impedimetric sensor with enhanced surface area and electrocatalytic activity.

Materials:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE): Serves as the conductive base transducer.

- Oxidized MWCNTs: Provide a high surface area and facilitate electron transfer.

- Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl4): Precursor for gold nanoparticle synthesis.

- Potassium Ferricyanide/Ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)6]3−/4−): Redox probe solution.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or KCl: Electrolyte solution.

- Target Analyte Standard: e.g., Mesna drug solution.

Procedure:

- Electrode Polishing: Polish the bare GCE sequentially with alumina slurries (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after each polish.

- MWCNT Dispersion: Prepare a homogeneous dispersion of oxidized MWCNTs (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in a suitable solvent like dimethylformamide (DMF) using ultrasonication.

- MWCNT Modification: Drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of the MWCNT dispersion onto the polished surface of the GCE and allow it to dry under ambient conditions to form the MWCNTs/GCE.

- AuNPs Electrodeposition: Immerse the MWCNTs/GCE in an aqueous solution of HAuCl4 (e.g., 0.5 mM in 0.1 M KNO3). Perform electrodeposition by cycling the potential (e.g., between -0.2 and +1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 10 cycles) to form AuNPs/MWCNTs/GCE.

- Sensor Characterization: Use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and EIS in a solution containing your chosen redox probe (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− in 0.1 M KCl) to confirm the successful modification. A significant decrease in Rct compared to the bare GCE indicates enhanced electron transfer kinetics.

Protocol 2: EIS Measurement and Analytical Calibration

This protocol describes the standard procedure for acquiring impedimetric data and constructing a calibration curve for quantitative analysis.

- Aim: To measure the charge transfer resistance (Rct) and establish a correlation with analyte concentration.

Materials:

- Fabricated sensor (e.g., from Protocol 1).

- Potentiostat with EIS capability.

- Electrochemical cell with Ag/AgCl reference and Pt counter electrodes.

- Redox probe in supporting electrolyte (e.g., 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− in 0.1 M KCl).

- Standard solutions of the target analyte at known concentrations.

Procedure:

- Baseline EIS Measurement: Place the modified sensor in the electrochemical cell containing the redox probe/electrolyte solution. Record the EIS spectrum at the formal potential of the redox probe (e.g., +0.22 V vs. Ag/AgCl for [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−). Typical parameters: frequency range from 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz, AC amplitude of 10 mV. This measurement provides the baseline Rct (Rct,0).

- Analyte Incubation: Incubate the sensor with a standard solution of the target analyte for a fixed duration under controlled conditions (e.g., 15 minutes at room temperature).

- Post-Incubation EIS Measurement: Rinse the sensor gently with the supporting electrolyte to remove unbound molecules. Re-immerse it in the fresh redox probe/electrolyte solution and record a new EIS spectrum under identical conditions. This provides Rct after analyte binding (Rct,A).

- Data Fitting: Fit the obtained Nyquist plots using the Randles equivalent circuit model to extract precise Rct values.

- Calibration Curve: Repeat steps 1-4 for at least five different standard concentrations of the analyte. Plot the relative change in charge transfer resistance, often expressed as (Rct,A - Rct,0)/Rct,0 or simply Rct,A, against the logarithm of the analyte concentration. Perform linear or non-linear regression to establish the quantitative relationship.

The workflow below summarizes this process from sensor preparation to data analysis.

Data Presentation & Analysis

Performance Comparison of Common Redox Probes

The choice of redox probe is critical and depends on the sensor surface and the intended application. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of two widely used probes.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Redox Probes in Faradaic EIS

| Property | [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− | [Ru(NH3)6]3+/2+ |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Transfer Kinetics | Quasi-reversible, surface-sensitive [12] | Near-ideal, outer-sphere [12] |

| Cost | Inexpensive [12] | High cost [12] |

| Key Advantage | Low cost, widely adopted | Insensitive to surface microstructure and moderate roughness [12] |

| Key Limitation | Sensitive to surface chemistry and surface states on carbon electrodes; kinetics can be influenced by surface functional groups [12] | High cost can be prohibitive for some laboratories [12] |

| Ideal Use Case | Preliminary characterization on metal electrodes; systems where cost is a primary driver | Accurate assessment of true electron transfer rates; studies on carbon-based or rough electrodes [12] |

Exemplary Analytical Performance

The following table presents performance data from real research to illustrate the sensitivity and dynamic range achievable with optimized Faradaic EIS sensors.

Table 2: Exemplary Analytical Performance of Reported Faradaic EIS Sensors

| Analyte | Sensor Platform | Redox Probe | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesna (anti-cancer drug) | AuNPs/MWCNTs /GCE [11] | [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− | 0.06 nM - 1.0 nM & 1.0 nM - 130.0 µM [11] | 0.02 nM [11] | Serum & urine samples [11] |

| Alpha-synuclein Oligomers (Parkinson's biomarker) | Aptamer/Au electrode [13] | [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− | Not specified | Good sensitivity and selectivity reported [13] | Buffer solution [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Faradaic EIS Sensing

| Item | Function/Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Probe | Generates the Faradaic current; its electron transfer is modulated by the analyte. | Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide ( [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− ) [11] [14] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries ionic current, minimizes solution resistance (Rs), and controls ionic strength. | Potassium Chloride (KCl), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [15] [14] |

| Electrode Modifiers | Enhance surface area, improve electron transfer kinetics, and provide sites for biorecognition. | MWCNTs, Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Graphene [11] |

| Biorecognition Element | Imparts selectivity by specifically binding the target analyte. | Antibodies, Aptamers, Enzymes, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [16] [13] |

| Repinotan hydrochloride | Repinotan Hydrochloride|5-HT1A Receptor Agonist | Repinotan hydrochloride is a potent, selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist for neuroscience research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| 3-Acetyl-5-bromopyridine | 3-Acetyl-5-bromopyridine | High Purity | For RUO | 3-Acetyl-5-bromopyridine: A versatile brominated & acetylated pyridine scaffold for pharmaceutical & materials research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Probe and Electrolyte Optimization: The concentration of the redox probe and the ionic strength of the background electrolyte significantly impact the Nyquist plot. Increasing ionic strength can shift the RC semicircle to higher frequencies. Optimization is required to achieve a clear, measurable semicircle in the accessible frequency range [15].

- Stability of Rct Baseline: Ensure the Rct of the sensor is stable in the pure redox solution before analyte introduction. Drifting baselines indicate an unstable modification layer or electrode fouling.

- Control Experiments: Always perform control experiments to confirm that the observed Rct change is due to specific analyte binding and not non-specific adsorption or changes in solution conditions.

- Circuit Model Validation: Use the Kramers-Kronig transforms to check the stability and linearity of the system. Ensure the chosen equivalent circuit model provides a good fit to the experimental data across the entire frequency range [9].

- Surface Regeneration: For reusable sensors, develop a gentle and effective regeneration protocol (e.g., a mild pH wash) that removes the bound analyte without damaging the biorecognition layer on the sensor surface.

The Randles circuit is a fundamental equivalent electrical model used to interpret the impedance response of electrochemical interfaces, particularly in faradaic processes central to redox sensing and biosensing research [17]. It provides a physical model for describing the processes at an electrode-solution interface where a dissolved electroactive species undergoes a reduction or oxidation reaction [18]. For researchers developing electrochemical sensors for drug analysis or diagnostic applications, mastering the Randles circuit is essential for extracting meaningful physicochemical parameters from impedance spectra, enabling the quantification of interfacial properties, reaction kinetics, and mass transport effects that define sensor performance.

This application note deconstructs the circuit's core components within the context of EIS-based redox sensing, providing detailed protocols for experimental measurement, data fitting, and interpretation relevant to biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Circuit Components and Their Physical Meaning

The Randles circuit models an electrochemical cell using a combination of passive electrical elements, each representing a distinct physical process at the electrode-solution interface [17]. A thorough understanding of each component is crucial for diagnosing sensor behavior and optimizing its design.

Table 1: Core Components of the Randles Circuit

| Component | Symbol | Physical Origin | Impedance Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Resistance | RΩ | Ionic resistance of the electrolyte solution between working and reference electrodes [17] | Z = RΩ [2] |

| Double Layer Capacitance | Cdl | Charge separation at the electrode-electrolyte interface, forming the electrochemical double-layer [3] [18] | Z = 1/(jωCdl) [2] |

| Charge Transfer Resistance | Rct | Resistance to electron transfer across the interface during a faradaic reaction [18] [17] | Z = Rct [2] |

| Warburg Impedance | W | Resistance due to diffusion of electroactive species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface [17] [19] | ZW = AW/√ω + AW/(j√ω) [17] |

The Complete Model and Its Spectrum

These components are combined such that the solution resistance, RΩ, is in series with a parallel combination of the double-layer capacitance, Cdl, and a series combination of the charge-transfer resistance, Rct, and the Warburg impedance, W [17]. The resulting Nyquist plot provides a distinctive fingerprint of the electrochemical system.

Figure 1: Randles circuit diagram showing component relationships. Rct and W are in series, and this series combination is in parallel with Cdl. The entire parallel network is in series with RΩ.

Experimental Protocol for EIS Measurement

This protocol outlines the steps for acquiring high-quality impedance spectra of a redox couple in solution, suitable for fitting to the Randles circuit model.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat with EIS Capability | Applies potential and measures current response. | Must include a frequency response analyzer (FRA); capable of 10 mHz to 100 kHz [18]. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Provides controlled electrochemical environment. | Cell vial, working electrode (e.g., 2 mm gold disk), counter electrode (platinum wire), reference electrode (Ag/AgCl) [3]. |

| Redox Probe | Provides the faradaic reaction for sensing. | 5 mM Potassium Ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6]) in supporting electrolyte [19]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes migration. | 1 M Potassium Chloride (KCl) or other inert salt. |

| Solvent | Dissolves redox probe and electrolyte. | Deionized Water, PBS buffer, or other appropriate solvent. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cell Setup: Clean the working electrode according to standard procedures (e.g., polishing for solid electrodes). Place the working, reference, and counter electrodes into the cell containing your redox probe solution in a supporting electrolyte [3].

- Establish DC Potential: Apply the DC potential (EDC) around the formal potential of the redox couple. For a reversible couple like Fe(CN)63-/4-, this is typically +0.22 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Allow the current to stabilize, indicating a steady-state condition [20].

- Configure EIS Parameters: Set the AC excitation parameters on the potentiostat.

- Frequency Range: Typically from 100 kHz to 100 mHz (or 10 mHz for full diffusion control) [18].

- AC Amplitude: A small, 10 mV sinusoidal perturbation is standard to ensure the system response is pseudo-linear [18] [2].

- Points per Decade: 5 to 10 points per frequency decade for sufficient spectral definition.

- Run EIS Measurement: Initiate the frequency sweep. The instrument will apply the sine wave at each frequency, measure the current response's amplitude and phase shift, and calculate the impedance [3].

- Data Quality Validation: Use instrument software to check quality indicators like Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) to verify linearity and Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) to ensure system stability during measurement. A THD below 5% is generally acceptable [20].

Data Interpretation and Analysis

The acquired EIS data is most commonly visualized using a Nyquist plot, which provides a characteristic shape for the Randles circuit.

Visualizing the Impedance Spectrum

Figure 2: Characteristic Nyquist plot of a Randles circuit, showing the high-frequency semicircle and low-frequency Warburg line.

Extracting Circuit Parameters

- Step 1: Estimate RΩ. Identify the left-most intercept of the impedance spectrum with the real (Z') axis. This value represents the uncompensated solution resistance, RΩ [21].

- Step 2: Estimate Rct. Determine the diameter of the semicircular portion of the spectrum. The difference between the real-axis value at the low-frequency end of the semicircle and RΩ gives the charge transfer resistance, Rct [21].

- Step 3: Calculate Cdl. The characteristic frequency (fmax) at the top of the semicircle (where -Z'' is maximum) is related to the time constant of the interface: Cdl = 1 / (2Ï€fmaxRct) [21].

- Step 4: Identify Diffusion Control. At lower frequencies, a straight line at a 45° angle indicates Warburg impedance, signifying that the overall reaction rate is limited by the diffusion of the electroactive species [17] [19].

Advanced Analysis: Equivalent Circuit Fitting

For precise quantification, experimental data should be fitted using EIS software.

- Select the Randles circuit model as the fitting function.

- Use the estimated values from the visual inspection as initial guesses for the fitting algorithm.

- Run a complex non-linear least squares (CNLS) fitting procedure to obtain refined values for RΩ, Cdl, Rct, and the Warburg coefficient, AW [17].

- Validate the fit by overlaying the simulated spectrum from the fitted parameters onto the experimental data.

Application in Redox Sensing Research

The parameters derived from the Randles circuit are powerful indicators of interfacial properties and reaction kinetics, directly applicable to biosensor development.

- Probing Surface Modification: Successful immobilization of a capture probe (e.g., an antibody or DNA strand) on an electrode surface creates an insulating layer. This hinders electron transfer of a solution-based redox probe ([Fe(CN)6]3-/4-), resulting in a measurable increase in Rct. This increase can be used to confirm and quantify functionalization [18].

- Detecting Binding Events: The specific binding of a target analyte (e.g., a protein or drug molecule) to the immobilized capture layer further impedes access to the redox probe. This is observed as a further increase in Rct, enabling the quantitative detection of the analyte. The change in Rct (ΔRct) can be correlated with analyte concentration.

- Diagnosing Sensor Performance: A significant Warburg impedance (45° line) at typical measurement frequencies suggests the sensor response is diffusion-limited rather than reaction-limited. This may indicate a need for optimization, such as reducing the measurement frequency, enhancing surface area, or improving stirring, to ensure the sensor's response is governed by the binding event itself.

The Randles circuit transforms a complex electrochemical interface into a quantifiable model. By systematically deconstructing its components and following rigorous experimental and analytical protocols, researchers can effectively design, characterize, and optimize sensitive EIS-based redox sensors for drug development and diagnostic applications.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique that has revolutionized the characterization of electrochemical systems, particularly in the field of redox sensing for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. As a non-destructive, label-free method, EIS provides kinetic and mechanistic data by probing the frequency-dependent impedance of an electrochemical interface [22]. In redox sensing, this enables the detailed study of electron transfer processes and mass transport phenomena that occur during biorecognition events, such as antibody-antigen interactions, substrate-enzyme reactions, or whole cell capturing [23]. The technique operates on the principle of applying a small-amplitude sinusoidal potential (typically 1-10 mV) to an electrochemical cell and measuring the current response across a wide frequency range (from μHz to MHz) [2] [22]. The resulting data, when visualized through Nyquist and Bode plots, offers a wealth of information about the system under investigation, allowing researchers to deconvolve complex processes into discrete elements with different time constants [22].

For researchers in drug development, EIS presents particular advantages for monitoring binding events in real-time without the need for fluorescent or radioactive labels, making it ideal for studying delicate biological interactions in their native states. The sensitivity of EIS to surface modifications enables the detection of low-abundance biomarkers when proper optimization is performed [15]. This application note provides a comprehensive guide to interpreting the primary visualization tools in EIS—Nyquist and Bode plots—with a specific focus on extracting meaningful information about electron transfer and diffusion processes critical to redox sensing applications.

Theoretical Background

Fundamental Principles of EIS

In EIS, a sinusoidal potential excitation signal is applied to an electrochemical system, and the resulting current response is measured. For a linear, time-invariant system, the response will be a sinusoid at the same frequency but shifted in phase [2]. The excitation potential is described by the equation:

[ Et = E0 \cdot \sin(\omega t) ]

where ( Et ) is the potential at time ( t ), ( E0 ) is the amplitude of the signal, and ( \omega ) is the radial frequency [23]. The relationship between radial frequency and applied frequency ( f ) is given by ( \omega = 2 \pi f ) [23].

The current response is described by:

[ It = I0 \cdot \sin(\omega t + \Phi) ]

where ( I_0 ) is the amplitude of the current signal, and ( \Phi ) is the phase shift between potential and current [23] [2].

Impedance (( Z )) is then defined as the complex ratio of potential to current:

[ Z = \frac{E}{I} = Z_0 \cdot (\cos\Phi + j\sin\Phi) ]

where ( Z ) is expressed in terms of magnitude ( Z_0 ) and phase shift ( \Phi ) [23] [2]. This complex impedance can be separated into real (( Z' )) and imaginary (( Z'' )) components:

[ Z = Z' + jZ'' ]

where ( Z' = |Z|\cos\Phi ) and ( Z'' = |Z|\sin\Phi ) [20].

Critical Requirements for Valid EIS Measurements

Two fundamental requirements must be met for reliable EIS measurements: linearity and stationarity. Electrochemical systems are inherently non-linear, but linearity can be approximated by using sufficiently small excitation amplitudes (typically 1-10 mV) [2] [20]. This ensures the system response is pseudo-linear within the small perturbation region around the operating point. Stationarity requires that the system remains stable throughout the measurement duration, which can range from minutes to hours depending on the frequency range scanned [2] [20]. Non-stationary distortion (NSD) and total harmonic distortion (THD) indicators can be used to validate these conditions, with THD values below 5% generally indicating acceptable linearity [20].

Data Representation and Interpretation

Nyquist Plots

The Nyquist plot represents one of the most common forms of EIS data visualization in electrochemical research. In this representation, the negative imaginary impedance (( -Z'' )) is plotted against the real part of the impedance (( Z' )) across all measured frequencies [21] [23]. Each point on the Nyquist plot corresponds to the impedance at a specific frequency, though the frequency values are not explicitly shown along the curve [2]. Conventionally, high-frequency data appears on the left side of the plot, while low-frequency data appears on the right [23] [2]. It is crucial to use an orthonormal scale (1:1 aspect ratio) for Nyquist plots to prevent visual distortion and misinterpretation of the data [20].

In a typical Nyquist plot of a Faradaic system, several distinct regions provide information about different processes:

- The high-frequency intercept with the x-axis represents the solution resistance (( R_s ))

- A semicircular region at higher frequencies corresponds to the charge transfer process

- A linear region at lower frequencies (at a 45° angle for an ideal system) represents mass transport limitations [23]

The diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot equals the charge transfer resistance (( R_{ct} )), a key parameter in redox sensing as it characterizes the kinetics of electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface [21] [24].

Bode Plots

The Bode plot provides an alternative representation of EIS data that explicitly shows frequency information. A Bode plot consists of two separate graphs: (1) the logarithm of impedance magnitude (( \log |Z| )) versus the logarithm of frequency (( \log f )), and (2) the phase shift (( \Phi )) versus ( \log f ) [21] [23]. This representation offers several advantages for certain applications, as all impedance information is clearly visible, and individual circuit components can be more easily understood compared to Nyquist plots [21].

In redox sensing applications, Bode plots are particularly valuable for:

- Identifying time constants of different processes through phase angle peaks

- Evaluating the capacitive behavior of the electrochemical double layer

- Assessing system stability across frequencies

- Determining the frequency range where diffusion processes dominate [23]

The Bode plot often shows a plateau in impedance magnitude at high frequencies (representing solution resistance), a sloping region at intermediate frequencies (related to charge transfer processes), and another plateau or different slope at low frequencies (indicating mass transport control) [3]. Simultaneously, the phase angle plot typically shows characteristic peaks that correspond to different time constants in the system.

Comparative Analysis of Plot Types

Table 1: Comparison of Nyquist and Bode Plots for EIS Data Representation

| Feature | Nyquist Plot | Bode Plot |

|---|---|---|

| Axes | -Z'' vs Z' (complex plane) | log|Z| vs log(f) and Φ vs log(f) |

| Frequency Information | Implicit (not directly visible) | Explicit (frequency is the x-axis) |

| Primary Strengths | Sensitive to small changes; popular in electrochemistry; easy parameter estimation for simple circuits | Clear visualization of frequency dependence; easier to identify individual components |

| Common Applications | Quick assessment of charge transfer resistance; corrosion studies; battery analysis | Capacitive system analysis; identifying time constants; system stability assessment |

| Interpretation Challenges | Frequency values not displayed; complex to understand for beginners | Requires reading two graphs simultaneously; less intuitive for complex circuits |

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

The Randles Circuit

The Randles circuit represents the most fundamental equivalent circuit model for describing a simple electrochemical system with a single electron transfer reaction, making it highly relevant to redox sensing applications [21] [22]. This circuit includes:

- Solution resistance (( R_s )): representing the ionic resistance of the electrolyte

- Double layer capacitance (( C_{dl} )): representing the capacitor formed at the electrode-electrolyte interface

- Charge transfer resistance (( R_{ct} )): representing the resistance to electron transfer across the interface

- Warburg impedance (( W )): representing mass transport limitations [21] [23]

In the Nyquist plot, the Randles circuit produces a characteristic semicircle at higher frequencies (from the parallel combination of ( C{dl} ) and ( R{ct} )) followed by a 45° linear region at lower frequencies (from the Warburg element) [21]. In Bode representation, the Randles circuit shows a phase angle peak corresponding to the time constant of the charge transfer process.

Circuit Elements and Their Physical Meaning

Table 2: Equivalent Circuit Elements and Their Physical Significance in Redox Sensing

| Circuit Element | Impedance Equation | Physical Meaning | Visual Representation in Plots |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | ( Z = R ) | Solution resistance (Rₛ) or charge transfer resistance (R_ct) | Nyquist: Point on x-axis Bode: Horizontal line for |Z|, 0° phase |

| Capacitor (C) | ( Z = 1/(j\omega C) ) | Double layer capacitance (C_dl) | Nyquist: Straight vertical line Bode: -1 slope for |Z|, -90° phase |

| Warburg (W) | ( Z = \sigma\omega^{-1/2}(1-j) ) | Semi-infinite diffusion | Nyquist: 45° line Bode: -0.5 slope for |Z|, 45° phase |

| Constant Phase Element (CPE) | ( Z = 1/[Q(j\omega)^n] ) | Non-ideal capacitance (surface heterogeneity) | Nyquist: Depressed semicircle Bode: Variable phase angle |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for EIS Measurement in Redox Sensing

This protocol outlines the standardized procedure for conducting EIS measurements in redox sensing applications, adapted from established methodologies with specific considerations for pharmaceutical and biosensing applications [24].

Electrode Preparation and System Setup

Working Electrode Preparation: Polish a 1-3 mm diameter platinum or gold working electrode for 30 seconds using a polishing cloth moistened with alumina slurry (0.05 μm). Rub the flat surface of the disc electrode with moderate pressure to ensure a mirror-like finish [24].

Electrode Cleaning: Rinse the electrode thoroughly with distilled water three times to remove all alumina particles, followed by rinsing with the solvent to be used in the experiment (e.g., dichloromethane for organic systems or purified water for aqueous systems) [24].

Counter Electrode Preparation: Anneal a platinum wire counter electrode in a butane burner flame for less than 1 second until it begins reddening, then quickly remove to avoid melting. Ensure the counter electrode surface area is significantly larger than the working electrode to minimize its contribution to the total impedance [24].

Reference Electrode Preparation: For non-aqueous systems, prepare a pseudo-reference electrode (e.g., silver wire) by annealing in a butane burner flame using the same method as the counter electrode. For aqueous systems, use a standard reference electrode such as Ag/AgCl [24].

Cell Assembly: Place all three electrodes into the electrochemical cell containing the analyte solution, ensuring they do not contact each other. Connect to the corresponding potentiostat cables marked WE (working electrode), CE (counter electrode), and RE (reference electrode) [24].

Solution Deaeration: Insert a gas delivery tube connected to an inert gas supply (argon or nitrogen) and bubble through the solution for 20 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen. Maintain a slight positive pressure of inert gas during measurements when oxygen sensitivity is a concern [24].

Cyclic Voltammetry Characterization

Initial CV Setup: Program the potentiostat for cyclic voltammetry with an initial potential of 0.0 V, switching potentials appropriate for the redox system under study (typically ±2.0 V for unknown systems), and a scan rate of 100 mV/s [24].

Preliminary CV: Run the cyclic voltammetry to identify the approximate formal potential (Eâ°) of the redox couple. Note the potential values at the maxima of the anodic and cathodic peaks and calculate their average to estimate Eâ° [24].

Internal Standard Addition: Add a small amount (approximately 10 mg) of ferrocene as an internal standard for non-aqueous systems. Deaerate for an additional 5 minutes to ensure mixing and complete dissolution [24].

Reference CV: Run an additional CV scan focusing on the region around the ferrocene/ferrocenium redox couple (typically -1.0 V to +1.0 V) to accurately determine the reference potential [24].

Formal Potential Determination: Calculate the formal potential of your target redox couple relative to the ferrocene/ferrocenium couple (Fc/Fcâº), which is typically used as an internal standard with Eâ° defined as 0 V [24].

EIS Measurement Procedure

Parameter Setup: Configure the potentiostat for potentiostatic EIS measurement with the following typical parameters [24]:

- DC potential: Set to the formal potential (Eâ°) of the redox couple determined from CV

- AC amplitude: 10 mV (ensure linearity conditions)

- Frequency range: 10 kHz to 100 Hz (preliminary) or 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz (comprehensive)

- Points per decade: 10-20 (logarithmically spaced)

- Wait time between measurements: 5 seconds (to ensure stability)

Preliminary Spectrum: Run an initial impedance spectrum to verify system behavior and signal quality.

Potential Mapping: For detailed kinetic analysis, program an automated potential staircase measurement with the following parameters [24]:

- Potential range: EⰠ± 0.2 V

- Potential increment: 0.01 V

- Number of spectra: 41 (for ±0.2 V range)

- Other parameters as in step 1

Data Collection: Initiate the automated EIS measurement series. The total measurement time will depend on the frequency range and points per decade but typically requires 2-3 minutes per spectrum [24].

Quality Validation: Monitor THD and NSD indicators during measurement to ensure data quality. THD should remain below 5% to verify linearity, and NSD should be minimal to confirm stationarity [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EIS in Redox Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | 0.1 M Buâ‚„NBFâ‚„ (for organic systems) or 0.1 M KCl/PBS (for aqueous systems) | Provides ionic conductivity; minimizes solution resistance |

| Redox Probe | 1-5 mM Ferro/ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») or [Ru(bpy)₃]²⺠| Generates Faradaic current; enhances sensitivity to surface changes |

| Working Electrode | Pt or Au disk (1-3 mm diameter) | Platform for electron transfer; surface for biorecognition element immobilization |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl (aqueous) or Ag wire (non-aqueous) | Provides stable reference potential for accurate potential control |

| Counter Electrode | Pt wire (large surface area) | Completes electrical circuit; prevents current limitation |

| Polishing Materials | Alumina slurry (0.05 μm) and polishing cloth | Ensizes reproducible electrode surface; removes contaminants |

| Solvent | Dichloromethane (organic) or buffer (aqueous) | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte; determines double layer structure |

| 5,7-Dihydroxy-4-Methylphthalide | 5,7-Dihydroxy-4-methylphthalide|CAS 27979-57-3 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-4-methylphthalide is a key precursor for mycophenolic acid biosynthesis. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| 6-Aldehydoisoophiopogonone A | 6-Aldehydo-isoophiopogonone A|CAS 112500-90-0|RUO |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analyzing Nyquist Plots for Electron Transfer and Diffusion

In redox sensing applications, the analysis of Nyquist plots focuses on extracting parameters related to electron transfer kinetics and mass transport limitations. The charge transfer resistance (( R_{ct} )) is obtained from the diameter of the semicircle in the high-frequency region and is inversely proportional to the standard rate constant of the electron transfer reaction [24]:

[ R_{ct} = \frac{RT}{nF} \cdot \frac{1}{k^0 \cdot A \cdot c} ]

where ( R ) is the gas constant, ( T ) is temperature, ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred, ( F ) is Faraday's constant, ( k^0 ) is the standard rate constant, ( A ) is the electrode area, and ( c ) is the concentration of the redox species [24].

For diffusion-controlled processes, the low-frequency region of the Nyquist plot shows a Warburg impedance, which appears as a straight line with a 45° slope for semi-infinite linear diffusion. The point where the semicircle transitions to the Warburg line provides information about the characteristic frequency of the diffusion process, from which the diffusion coefficient can be calculated [23].

In the context of redox sensing, changes in ( R{ct} ) are particularly important as they often indicate binding events or surface modifications that affect electron transfer kinetics. For example, when a target molecule binds to a capture probe immobilized on the electrode surface, it typically increases ( R{ct} ) by creating an additional barrier to electron transfer, enabling quantitative detection of the target analyte [15].

Extracting Parameters from Bode Plots

Bode plots provide complementary information that is particularly valuable for identifying processes with different time constants. The frequency at which the phase angle reaches a maximum (( f_{max} )) is related to the time constant (( \tau )) of the corresponding process [22]:

[ \tau = \frac{1}{2\pi f{max}} = R{ct} \cdot C_{dl} ]

This relationship allows researchers to deconvolve processes with similar resistances but different time constants, which is common in complex biological systems where multiple processes occur simultaneously.

The magnitude plot also provides information about the dominant process at different frequency regimes:

- At high frequencies: ( |Z| ) approaches ( R_s ) (solution resistance)

- At intermediate frequencies: The slope of ( \log |Z| ) vs ( \log f ) indicates the dominant process (-1 for capacitive, -0.5 for diffusion)

- At low frequencies: ( |Z| ) approaches ( Rs + R{ct} ) for kinetically controlled systems or shows continued decrease for diffusion-controlled systems

Equivalent Circuit Modeling and Validation

After collecting EIS data, researchers typically fit the results to an equivalent circuit model to extract quantitative parameters. The following protocol outlines this process:

Circuit Selection: Start with the simplest plausible circuit (e.g., a modified Randles circuit) and progressively increase complexity if needed [24].

Initial Parameter Estimation: Estimate initial values for circuit elements based on the EIS plot:

- ( R_s ): High-frequency intercept on Nyquist plot

- ( R_{ct} ): Diameter of the semicircle

- ( C{dl} ): Estimate from ( C{dl} = 1/(2\pi f{max} R{ct}) ) where ( f_{max} ) is the frequency at the top of the semicircle

Non-linear Least Squares Fitting: Use specialized software (e.g., ZView, EC-Lab, or similar) to perform non-linear least squares fitting of the model to the experimental data [24].

Goodness-of-Fit Evaluation: Assess the quality of the fit using parameters such as χ² value (should be <10â»Â³ for a good fit) and visual inspection of residuals [24].

Model Validation: Apply the Kramers-Kronig relations to test the validity of the data, ensuring compliance with linearity, causality, and stability conditions [22].

Parameter Error Assessment: Check the relative errors of fitted parameters. If any parameter has an error exceeding 100%, consider simplifying the model as that parameter may not be necessary [24].

Advanced Applications in Redox Sensing

The integration of EIS with redox sensing has enabled significant advances in biomedical research and drug development. Recent studies have demonstrated the utility of EIS in detecting various analytes including pathogens, DNA biomarkers, cancer-associated proteins, and emerging chemical contaminants [23] [15]. The exceptional sensitivity of EIS stems from its ability to detect minor changes in interfacial properties resulting from biorecognition events.

Nanomaterials have played a crucial role in enhancing EIS-based biosensors by providing catalytic activity, facilitating sensing element immobilization, promoting faster electron transfer, and increasing reliability [23]. For example, the incorporation of nanoparticles, nanotubes, and nanocomposites has been shown to significantly improve the analytical performance of impedimetric biosensors [23].

Recent research has also focused on optimizing electrolyte and redox probe systems to enhance sensitivity. Studies have shown that by carefully controlling the ionic strength of the background electrolyte and the concentration of the redox probe, researchers can tune the frequency response of the system to maximize sensitivity to specific binding events [15]. This optimization has enabled the transition from expensive laboratory impedance analyzers to more affordable portable systems, making EIS-based sensing more accessible for point-of-care applications [15].

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

Common Issues and Solutions

Non-Linear Response: If THD values exceed 5%, reduce the AC amplitude (while maintaining adequate signal-to-noise ratio) or verify that the DC potential is correctly set [20].

Non-Stationary Behavior: If NSD indicates time-variance, ensure system stability by controlling temperature, minimizing evaporation, and verifying that electrochemical processes are at steady-state before measurement [20].

Noisy Low-Frequency Data: Increase the number of measurement cycles per frequency or apply digital filtering to improve signal quality at low frequencies where measurement time is longest.

Poor Fitting Results: Verify the appropriateness of the equivalent circuit model, check for unaccounted-for processes, and ensure data quality meets Kramers-Kronig criteria [22] [24].

Irreproducible Results: Standardize electrode preparation procedures, ensure consistent surface cleaning, and verify electrolyte composition and degassing protocols [24].

Optimization Strategies for Redox Sensing

Redox Probe Selection: Choose redox probes with formal potentials that do not interfere with the biological system under study. Common choices include ferro/ferricyanide for aqueous systems and ferrocene derivatives for organic systems [15].

Surface Modification: Optimize the density of capture probes on the electrode surface to balance accessibility for target binding with sufficient spacing to minimize steric hindrance.

Frequency Range Selection: Focus on the frequency range that is most sensitive to the process of interest. For binding-induced changes in charge transfer, the frequency around the phase maximum typically provides the greatest sensitivity.

Signal Normalization: Always normalize impedance parameters to electrode surface area when comparing between different electrodes or experiments.

Through proper implementation of the protocols and interpretation methods outlined in this application note, researchers can leverage the full power of EIS for advancing redox sensing applications in drug development and biomedical research.

Why Linearity and Stationarity are Non-Negotiable for Reliable EIS Measurements

In the field of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) for redox sensing, the reliability of data interpretation hinges on fulfilling two fundamental system requirements: linearity and stationarity. These conditions are not merely advantageous but are absolute prerequisites for obtaining physically meaningful results that can accurately describe electrochemical interfaces and processes. EIS functions by applying a small sinusoidal perturbation to an electrochemical system and analyzing the resulting response [20]. The technique is founded on the assumption that the system under study behaves as a Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) system for the duration of the measurement [20]. Violations of either linearity or stationarity introduce significant distortions, rendering the resulting impedance data invalid and leading to erroneous conclusions in redox sensing research. This application note details the theoretical and practical aspects of these requirements, providing validated protocols to ensure data integrity.

Theoretical Underpinnings

The Principle of Linearity

Electrochemical systems are inherently non-linear, as described by fundamental relationships such as the Butler-Volmer equation for charge-transfer kinetics. The principle of linearity stipulates that the response of the system (current output) must be directly proportional to the perturbation (voltage input) [20]. In practice, this condition is achieved not by altering the system's intrinsic properties, but by restricting the measurement to a sufficiently small amplitude perturbation. As shown in Figure 1, a small enough excitation signal ensures that the system's response approximates the tangent of its steady-state current-potential curve, creating an effectively linear region around the operating point (DC bias) [20]. This small-signal approximation is critical for applying the fundamental laws of impedance.

The Principle of Stationarity

The principle of stationarity, or time-invariance, requires that the properties of the electrochemical system being measured remain constant throughout the entire duration of the impedance frequency sweep [20]. Any significant drift in parameters—such as surface concentration of redox species, electrode active area due to corrosion or deposition, or temperature—violates this condition. A system must first be in a steady-state (not in a transient phase) before an EIS measurement begins, and must maintain that state during the measurement. This is particularly challenging in systems involving dynamic interfacial changes, such as the cycling of lithium metal electrodes, where operando EIS requires specialized approaches to deconvolute these changes [25].

Consequences of Violating LTI Conditions

Effects of Non-Linearity

When the applied perturbation amplitude is too large, the system operates outside the linear regime. This non-linearity manifests in the impedance response through several artifacts:

- Harmonic Distortion: The current response waveform contains frequency components (harmonics) that are integer multiples of the input frequency, which are not accounted for in standard LTI theory [20].

- Inaccurate Circuit Parameters: The extracted values for components in the equivalent circuit model (e.g., charge-transfer resistance, double-layer capacitance) become dependent on the excitation amplitude, losing their physical meaning.

- Kramers-Kronig Violations: The measured impedance spectrum will fail the Kramers-Kronig test, which is a fundamental validity check based on the causality and linearity of the system [26].

Effects of Non-Stationarity

A system that evolves during measurement leads to non-stationarity, causing:

- Time-Variant Impedance: The impedance at a given frequency changes between the start and end of the measurement, creating a self-contradictory dataset.

- Unphysical Model Fits: The resulting Nyquist or Bode plots may exhibit strange shapes, such as "drunk" or kinked semicircles, that do not correspond to any physical equivalent circuit and are impossible to fit robustly.

- Misleading Trends: In long-term studies, such as corrosion monitoring or battery cycling, non-stationarity can obscure genuine performance trends and degradation mechanisms [27] [25].

Table 1: Troubleshooting LTI Requirement Violations in EIS

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low-frequency data scatter in Nyquist plot | System drift (Non-stationarity) | Ensure system is at steady-state; use faster measurement; monitor open-circuit potential for stability. |

| Inconsistent ( R_{ct} ) values with different excitation amplitudes | Excessive perturbation (Non-linearity) | Perform amplitude sweep; reduce excitation amplitude until measured impedance is stable. |

| Failed Kramers-Kronig validation | Combined non-linearity and non-stationarity | Systematically reduce amplitude and verify system stability before and after measurement. |

| "Kinked" or distorted semicircles | Severe non-stationarity during measurement | Check for temperature fluctuations, reactant depletion, or surface fouling. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol for Verifying Linearity

This protocol uses the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) method to quantitatively determine the maximum permissible excitation amplitude.

Research Reagent Solutions & Equipment:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: Capable of performing EIS with THD analysis (e.g., instruments from BioLogic or comparable suppliers).

- Electrochemical Cell: Standard three-electrode setup relevant to your redox sensing application.

- Electrolyte & Redox Probe: e.g., 1 mM ( \text{K}3[\text{Fe(CN)}6] / \text{K}4[\text{Fe(CN)}6] ) in 1 M KCl, as a stable benchmark redox couple.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Setup: Set your electrochemical cell to the desired DC potential (e.g., the formal potential of the redox couple).

- Initial Measurement: Perform a preliminary EIS measurement with a reasonably small amplitude (e.g., 10 mV RMS). Note the impedance.

- Amplitude Sweep: Conduct a series of EIS measurements over the same frequency range (e.g., 100 kHz to 100 mHz) while systematically increasing the excitation amplitude (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 mV RMS). It is critical that the system remains stationary throughout this series.

- THD Analysis: For each measurement, use the potentiostat's software to calculate the Total Harmonic Distortion. THD quantifies the percentage of the output signal's power that is found in the harmonics rather than the fundamental frequency.

- Determine Linear Amplitude: Identify the maximum amplitude for which the THD remains below the recommended threshold of 5% across the frequency spectrum [20]. The corresponding impedance spectrum is your valid, linear response.

Protocol for Verifying Stationarity

This protocol uses the Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) indicator and open-circuit potential monitoring to assess stability.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pre-Measurement Equilibrium: After applying the DC bias, monitor the current until it stabilizes to a steady-state value, indicating the system is ready for measurement.

- Open-Circuit Potential (OCP) Check: For a period before and after the EIS measurement, switch to open-circuit conditions and monitor the potential. A stable OCP indicates a stable interface.

- NSD Monitoring: During the EIS measurement, enable the NSD indicator. Similar to THD, NSD uses specific signal analysis to detect distortions caused by temporal changes in the system.

- Data Validation: Analyze the NSD results. EIS data at frequencies where the NSD exceeds a critical value (often around 5-10%) should be considered unreliable and discarded [20]. The measurement may need to be repeated with a faster sweep or after the system has achieved better stability.

- Post-Measurement Check: Compare the high-frequency impedance data (e.g., the solution resistance, ( R_s )) from the beginning and end of the measurement. A significant change indicates non-stationarity.

Diagram 1: Workflow for reliable EIS measurement, integrating checks for stationarity (OCP, NSD) and linearity (THD).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for EIS in Redox Sensing

| Item Name | Function / Rationale | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ferri/Ferrocyanide Redox Couple (( \text{[Fe(CN)_6]^{3-/4-} })) | Well-understood, reversible outer-sphere redox probe for validating sensor function and EIS setup. | Benchmarking new electrode materials; testing EIS protocol parameters. |

| Stable Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) | Provides a constant potential reference, critical for maintaining a stable DC bias point. | All potentiostatic EIS measurements in three-electrode cells. |

| High-Purity Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, PBS) | Dominates solution conductivity, minimizes ohmic drop, and suppresses migration of the redox species. | Creating a defined electrochemical environment for redox sensing. |

| THD/NSD-Capable Potentiostat | Instrumentation that provides quantitative, frequency-resolved indicators of linearity (THD) and stationarity (NSD). | Ensuring the validity of every EIS measurement during method development. |

| 5-Amino-8-hydroxyquinoline | 5-Aminoquinolin-8-ol | High-Purity Reagent | RUO | 5-Aminoquinolin-8-ol: A high-purity chelating agent & synthon for catalytic and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 5-Acetylsalicylic acid | 5-Acetylsalicylic acid, CAS:13110-96-8, MF:C9H8O4, MW:180.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Considerations in Redox Sensing

The stringent requirements for linearity and stationarity become even more critical when EIS is applied to complex redox sensing scenarios, such as the study of DNA self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold before and after hybridization [28]. In these systems, the interface evolves during the experiment. Similarly, in operando studies of batteries, where impedance is measured during charging/discharging, the system is inherently non-stationary [25]. Advanced techniques like Dynamic EIS (DEIS) are being developed to address these challenges. These methods use faster measurements or specialized signal processing to "freeze" the system's state in time, but they still rely on the fundamental principles of operating in a pseudo-linear regime to extract valid impedance values [25].

Adherence to the principles of linearity and stationarity is the cornerstone of generating reliable, high-quality EIS data in redox sensing research. Linearity, ensured through the use of minimally perturbing excitation amplitudes validated by THD analysis, guarantees that the system's response can be accurately described by impedance theory. Stationarity, confirmed via OCP stability and NSD monitoring, ensures that the measured impedance is a self-consistent representation of a single system state. The experimental protocols provided herein offer a systematic approach to validating these non-negotiable conditions, thereby strengthening the foundation for all subsequent data interpretation and modeling in electrochemical biosensing.

Building and Applying EIS Biosensors: From Electrode Modification to Real-World Assays

Step-by-Step Guide to Faradaic EIS (Bio)sensing Assay Development

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique that characterizes the electrical response of an electrochemical system by applying a small-amplitude sinusoidal alternating current (AC) potential across a range of frequencies and measuring the resulting current response [29] [20]. In faradaic EIS, a redox-active molecule (e.g., ferro/ferricyanide) is added to the solution, and the technique specifically monitors the changes in impedance related to the charge transfer resistance ((R{ct})) of the reversible redox reaction at the electrode interface [29] [30]. This change in (R{ct}) is highly sensitive to surface modifications, making faradaic EIS an exceptional label-free transduction method for detecting biomolecular interactions, such as antigen-antibody binding, nucleic acid hybridization, and receptor-ligand interactions [31] [30]. The technique is particularly valued for its high sensitivity, minimal sample volume requirements (~<20 µL), rapid analysis times, and ability to provide real-time, quantitative data without disturbing the sample, making it ideal for point-of-care diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and drug discovery [29] [31].

Theoretical Foundation

Key Principles and the Randles Circuit

In a typical faradaic EIS experiment, the binding of a target analyte to a biorecognition element (e.g., an antibody, aptamer, or enzyme) immobilized on the electrode surface creates a physical barrier. This barrier hinders the electron transfer between the electrode surface and the redox probe in solution, leading to an increase in the measured charge transfer resistance ((R{ct})) [30] [32]. This increase in (R{ct}) directly correlates with the concentration of the target analyte [30].

The electrochemical behavior of a simple system in a faradaic EIS experiment is most commonly modeled using the Randles equivalent circuit [30] [32]. This circuit deconstructs the total impedance of the electrode-electrolyte interface into fundamental physical components. Table 1 describes the key elements of this circuit.

Table 1: Key Components of the Randles Equivalent Circuit

| Circuit Element | Symbol | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Resistance | (R_s) | The ohmic resistance of the electrolyte solution between the working and reference electrodes. |

| Constant Phase Element | (CPE) | Represents the non-ideal, frequency-dependent capacitance of the electrochemical double layer. A CPE is used instead of a pure capacitor to account for surface roughness, inhomogeneity, and porosity [30]. |

| Charge Transfer Resistance | (R_{ct}) | The resistance to electron transfer of the redox reaction at the electrode interface. This is the primary parameter measured in faradaic EIS biosensing. |

| Warburg Impedance | (W) | Represents the impedance related to the diffusion of redox species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface. It is dominant at low frequencies. |

The impedance data is typically visualized using a Nyquist plot (-Z''im vs. Z're), where a semicircle at high frequencies corresponds to the electron transfer kinetics ((R{ct}) and (CPE)), and a linear tail at low frequencies represents diffusion control (Warburg impedance) [30] [20]. The diameter of the semicircle is equal to (R{ct}).

Beyond the Basic Randles Circuit

While the simple Randles circuit is widely used, modern (bio)sensors often employ electrodes modified with functional materials, polymers, or nanomaterials. These coatings can radically alter the impedance profile, introducing additional time constants [30] [32]. In such cases, the basic Randles circuit may be insufficient, and modified versions with additional circuit elements (e.g., extra R-CPE combinations in series or parallel) are required to accurately fit the EIS data and describe the more complex physical processes [30].

Experimental Design and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing a faradaic EIS biosensing assay, from electrode preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|